Face : an Interdisciplinary Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Golem Allegories

IRIE International Review of Information Ethics Vol. 26 (12/2017) Ivan Capeller: The Golem Allegories This is the first piece of a three-part article about the allegorical aspects of the legend of the Golem and its epistemological, political and ethical implications in our Internet plugged-in connected times. There are three sets of Golem allegories that may refer to questions relating either to language and knowledge, work and technique, or life and existence. The Golem allegories will be read through three major narratives that are also clearly or potentially allegorical: Walter Benjamin’s allegory of the chess player at the very beginning of his theses On the Concept of History, William Shakespeare’s last play The Tempest and James Cameron’s movie The Terminator. Each one of these narratives is going to be considered as a key allegory for a determinate aspect of the Golem, following a three-movement reading of the Golem legend that structures this very text as its logical outcome. Agenda: The Golem and the Chess Player: Language, Knowledge and Thought........................................ 79 Between Myth and Allegory ................................................................................................................. 79 Between the Puppet and the Dwarf ..................................................................................................... 82 Between Bio-Semiotics and Cyber-Semiotics ........................................................................................ 85 Author: Prof. Dr. Ivan Capeller: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação (PPGCI) e Escola de Comunicação (ECO) da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro/RJ, [email protected] Relevant publications: - A Pátina do Filme: da reprodução cinemática do tempo à representação cinematográfica da história. Revista Matrizes (USP. Impresso) , v. V, p. 213-229, 2009 - Kubrick com Foucault, o desvio do panoptismo. -

The Life and Works of Beatrice Elvery, 1881-1920

Nationalism, Motherhood, and Activism: The Life and Works of Beatrice Elvery, 1881-1920 Melissa S. Bowen A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History May 2015 Copyright By Melissa S. Bowen 2015 Acknowledgments I am incredibly grateful for the encouragement and support of Cal State Bakersfield’s History Department faculty, who as a group worked closely with me in preparing me for this fruitful endeavor. I am most grateful to my advisor, Cliona Murphy, whose positive enthusiasm, never- ending generosity, and infinite wisdom on Irish History made this project worthwhile and enjoyable. I would not have been able to put as much primary research into this project as I did without the generous scholarship awarded to me by Cal State Bakersfield’s GRASP office, which allowed me to travel to Ireland and study Beatrice Elvery’s work first hand. I am also grateful to the scholars and professionals who helped me with my research such as Dr. Stephanie Rains, Dr. Nicola Gordon Bowe, and Rector John Tanner. Lastly, my research would not nearly have been as extensive if it were not for my hosts while in Ireland, Brian Murphy, Miriam O’Brien, and Angela Lawlor, who all welcomed me into their homes, filled me with delicious Irish food, and guided me throughout the country during my entire trip. List of Illustrations Sheppard, Oliver. 1908. Roisin Dua. St. Stephen's Green, Dublin. 2 Orpen, R.C. 1908. 1909 Seal. The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland, Dublin. -

Pete Townshend White City (A Novel) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pete Townshend White City (A Novel) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: White City (A Novel) Country: Canada Released: 1985 Style: Art Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1176 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1532 mb WMA version RAR size: 1440 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 163 Other Formats: AA DTS TTA WAV AHX MP3 RA Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Give Blood 5:44 A2 Brilliant Blues 3:06 A3 Face The Face 5:51 A4 Hiding Out 3:00 A5 Secondhand Love 4:12 B1 Crashing By Design 3:14 B2 I Am Secure 4:00 White City Fighting B3 4:40 Written-By – Dave Gilmour*, Pete Townshend B4 Come To Mama 4:40 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – WEA Music Of Canada, Ltd. Distributed By – WEA Music Of Canada, Ltd. Credits Arranged By [Kick Horns] – Kick Horns* Backing Vocals – Emma Townshend, Jackie Challenor, Lorenza Johnson, Mae McKenna Design, Art Direction [Direction], Photography By [Inner Sleeve] – Richard Evans Engineer [Assistant] – Chris Ludwinski, Dave Edwards , Jules Bowen Performer – Chucho Merchan, Clem Burke, Dave Gilmour*, John (Rabbit) Bundrick*, Mark Brzezicki, Pete Townshend, Peter Hope-Evans*, Phil Chen, Pino Palladino, Simon Phillips, Steve Barnacle, Tony Butler Performer [Kick Horns] – Dave Sanders, Peter Thoms, Roddy Lorimer, Simon Clarke , Tim Sanders Performer [Recitation] – Ewan Stewart Photography By [Front Cover] – Alex Henderson Photography By [Inner Sleeve] – Malcolm Heywood Producer – Chris Thomas Recorded By – Bill Price Written-By – Pete Townshend Notes Recorded at Eel Pie Studio, Twickenham; Eel Pie Studio, Soho, London; A.I.R. Studios, London. ℗© 1985 Eel Pie Recording Productions Ltd. Released with a printed inner photo/credits/lyrics-sleeve Distinct from release Pete Townshend - White City (A Novel) due to variation in the centre label image. -

Acta Universitatis Carolinae Philologica 3/2015 Translatologica Pragensia Ix

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PHILOLOGICA 3/2015 TRANSLATOLOGICA PRAGENSIA IX ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PHILOLOGICA 3/2015 TRANSLATOLOGICA PRAGENSIA IX Editors JANA KRÁLOVÁ, DAVID MRAČEK, STANISLAV RUBÁŠ CHARLES UNIVERSITY IN PRAGUE KAROLINUM PRESS 2015 Editors: Jana Králová (Charles University in Prague) David Mraček (Charles University in Prague) Stanislav Rubáš (Charles University in Prague) Peer-reviewed by Edita Gromová (Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra) Bohuslav Mánek (University of Hradec Králové) http://www.karolinum.cz/journals/philologica © Charles University in Prague, 2015 ISSN 0567-8269 CONTENTS Elżbieta Tabakowska: Translation studies meets linguistics: pre-structuralism, structuralism, post-structuralism .................................................... 7 Lorenzo Costantino: Structuralism in translation theories in Poland: some remarks on the “Poznań school” ............................................... 19 Brigitte Schultze: Jiří Levý’s contributions to drama translation revisited ................ 27 Piotr de Bończa Bukowski, Magda Heydel: Polish studies in translation: re-mapping an interdisciplinary field ................................................ 39 Petr Eliáš: Individual style in translation ............................................... 55 Elisabeth Gibbels, Jo Schmitz: Investigating interventionist interpreting via Mikhail Bakhtin ................................................................ 61 Zuzana Jettmarová: How many functionalisms are there in translation studies? .......... 73 -

Enjoy the Spooktacular Stories!

HAPPY GRAND COUNTY LIBRARY DISTRICT SCARY STORY WINNERS ENJOY THE SPOOKTACULAR STORIES! THEY ARE UNEDITED TO MAINTAIN ORIGINALITY Page 2 Grand County Library District Scary Story Winners October 29, 2020 Grand Gazette www.GrandGazette.net into a hundred pieces. So Josh took 3rd Place Kremmling/HSS the treasure and went home. The Puppy That Said Boo! Kremmling/HSS K-2nd grade by Critter Wood 3rd grade 2nd Place 1st Place The Ghost and Skelly Once upon a time, there was a dog 1st Place Josh’s Scary Halloween by Brynlie Vrbas that said Boo! The dog loved to say Treasure of Ascaban Adventure Boo! He loved to say Boo to every by Danica Rector person in town. He also loved to scare by Grayson Rector Once upon a time, there was a skeleton named Skelly. He loved them when he growled Grrrr!!! He It all started on a cloudy, but warm Josh was at his house on a to scare people because he wanted loved to say “Boo and Grrr!!!” He Friday, October 16th. Jack’s mom Halloween night, he was getting his the whole neighborhood to himself. loved to scare people because he was said that he was going to go boating costume out but he decided to go When he scared everyone, they all a Halloween puppy. He really loved with his grandpa Alfred and best find a golden treasure to make his ran away to the desert. The people to scare his Mommy! He would put friend Jayson. Jack was so excited he costume with golden on it to make met Skelly in the desert and then a out his fangs and stick out his tongue. -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

You're Not Punk & I'm Telling Everyone

Vol. 6 october 2014 — issue 10issue INSIDE: you’re not punk & I’m telling everyone - the death of the ipod - Ex-optimists tour diary - introvisionaire - first draft: pumpkin beers - LINE OUT: JEALOUS CREATURES - from the heart - lp reviews - concert calendar The death of the ipod Last month a little bit of news out of Culper City was swept under the rug during Apple’s big announce- ment of the new range of iPhones and the iWatch thingy. Apple had announced the end of the iPod Classic line. Meaning that Apple would no longer make any high capacity 979Represent is a local magazine portable devices. I nearly cried. for the discerning dirtbag. You see, I’m an old school iPod devotee. I’ve owned countless iPods since Apple began supporting Windows for iTunes in 2004. My first iPod wouldn’t carry a charge for more than an hour at a Editorial bored time and had to be plugged in all the time, sported a paltry 20GB of memory and had a row of buttons above the signature click Kelly Minnis - Kevin Still wheel. For the past six years I’ve owned a couple of different 160GB iPod Classics. These are a compromise for me, as my music collection is far greater than 160GB. But I can carry around a good portion of my favorite music everywhere I go in a Art Splendidness package that’s smaller than a cassette tape. Who knows how Katie Killer - Wonko The Sane many iPods have sold over the years, but the number has to be in the hundreds of millions. -

Transferir Download

TRANSLATION MATTERS Special Issue: Intersemiotic Translation and Multimodality Volume 1, Issue 2, Autumn 2019 Editor Karen Bennett Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies (CETAPS) NOVA-FCSH, Lisbon, Portugal Cover Design Mariana Selas Publisher Faculty of Letters, University of Porto ISSN 2184-4585 Academic Advisory Board Jorge Almeida e Pinho (FLUP) Fernando Alves (U. Minho) Alexandra Assis Rosa (FLUL) Jorge Bastos da Silva (FLUP) Rita Bueno Maia (UCP) Rui Carvalho Homem (FLUP) Maria Zulmira Castanheira (FCSH) Rute Costa (FCSH) Gualter Cunha (FLUP) João Ferreira Duarte (FLUL) Elena Galvão (FLUP) Gabriela Gândara (NOVA-FCSH) Maria António Hörster (FLUC) Alexandra Lopes (UCP) John Milton (U. São Paulo) Maeve Olohan (U. Manchester) Hanna Pieta (FLUL) Cornelia Plag (FLUC) Rita Queiroz de Barros (FLUL) Miguel Ramalhete (FLUP) Iolanda Ramos (FCSH) Maria Teresa Roberto (UA) Margarida Vale de Gato (FLUL) Fátima Vieira (FLUP) Editorial Assistant Gisele Dionísio da Silva Book Reviews Editor Elena Zagar Galvão Copyright The articles published in this volume are covered by the Creative Commons “AttributionNonCommercial-NoDerivs” license (see http://creativecommons.org). They may be reproduced in its entirety as long as Translation Matters is credited, a link to the journal’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The articles may not be reproduced in part or altered in form, or a fee charged, without the journal’s permission. Copyright remains solely with individual authors. The authors should let the journal Translation Matters know if they wish to republish. Translation Matters is a free, exclusively online peer-reviewed journal published twice a year. It is available on the website of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Porto http://ler.letras.up.pt. -

Standing up for Science Fiction

FI Aug-Sept 2006 Pages 6/30/06 9:34 AM Page 53 HUMANISM AND THE ARTS commercial SF and work free of ulterior motives. No one would have defended Standing Up for the view that Lem’s acceptance of an honorary membership included the pre- condition that he should hold his tongue, yet the shameful way he was treated Science Fiction amounted to a belated enforcement of such a condition. Charitably, one might say that people Stanislaw Lem (1921–2006) with the power to enforce their wills lost their tempers and only embarrassed themselves by giving Lem some publici- George Zebrowski ty. In protest, famed author Ursula K. Le Guin declined SFWA’s annual Nebula Roman Kojzar, from the collection of David Williams Roman Kojzar, Award in the short-story catego- ry. Incredibly, the quietly substi- tanislaw Lem, the most tuted second-place winner re- celebrated writer of sci- peated a false charge against Sence fiction (SF) since Lem at the awards banquet. I sat Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, died at the ceremony and spoke up, in late March. An exacting but was shushed. thinker and craftsman, Lem Along with a dozen other challenged his Western col- writers, I protested Lem’s ous- leagues to live up to the poten- ter, and we documented the his- tials of science fiction by reex- tory in a scholarly journal. I hold amining a debate over how to the archival evidence, which shape imaginative narratives includes one celebrated writer that is as old as the genre itself. falsely stating, in print, that Lem I first learned about Lem in had criticized Western SF in the late 1960s, when a seafaring order to gain favor with Poland’s friend of my parents hand car- communist government. -

WCXR 2004 Songs, 6 Days, 11.93 GB

Page 1 of 58 WCXR 2004 songs, 6 days, 11.93 GB Artist Name Time Album Year AC/DC Hells Bells 5:13 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Back In Black 4:17 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 3:30 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Have a Drink on Me 3:59 Back In Black 1980 AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:12 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC Squealer 5:14 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC Big Balls 2:38 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt… 1976 AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) 5:44 For Those About to R… 1981 AC/DC Highway to Hell 3:28 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Girls Got Rhythm 3:24 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Beating Around the Bush 3:56 Highway to Hell 1979 AC/DC Let There Be Rock 6:07 Let There Be Rock 1977 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 5:23 Let There Be Rock 1977 Ace Frehley New York Groove 3:04 Ace Frehley 1978 Aerosmith Make It 3:41 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Somebody 3:46 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Dream On 4:28 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith One-Way Street 7:02 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Mama Kin 4:29 Aerosmith 1973 Aerosmith Rattkesnake Shake (live) 10:28 Aerosmith 1971 Aerosmith Critical Mass 4:52 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Draw The Line 3:23 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Milk Cow Blues 4:11 Draw the Line 1977 Aerosmith Livin' on the Edge 6:21 Get a Grip 1993 Aerosmith Same Old Song and Dance 3:54 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Lord Of The Thighs 4:15 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Woman of the World 5:50 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Train Kept a Rollin 5:33 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Seasons Of Wither 4:57 Get Your Wings 1974 Aerosmith Lightning Strikes 4:27 Rock in a Hard Place 1982 Aerosmith Last Child 3:28 Rocks 1976 Aerosmith Back In The Saddle 4:41 Rocks 1976 WCXR Page 2 of 58 Artist Name Time Album Year Aerosmith Come Together 3:47 Sgt. -

GLITCH: DOPPELGÄNGER & POSTDIGITAL A-LÊTHEIA Angela

GLITCH: DOPPELGÄNGER & POSTDIGITAL A-LÊTHEIA Angela McArthur 13902293 Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Degree: Master of Art: Sound & Image MU898 (2013/2014) UNIVERSITY OF KENT Medway Campus August 2014 Total word count: 8805 Approved by: ________________________ Date: _______________________________ Copyright © 2014 Angela McArthur ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors Simon Clarke and Julie-Louise Bacon for their invaluable input, encouragement and generosity of spirit. I was lucky to have such conscientiousness support. I am grateful to my course-peers for their camaraderie, and to the willing participants of this study who gave freely of themselves. I am indebted to Ravensbourne College, and the University of Kent, for funding this work. Finally, I would like to thank Stefano Kalonaris, for providing a counter- balance of stability to my glitchiness, often without realising. Does knowledge of one’s affect diminish, or augment? The revealed trail of intent is as a fractal of self-consciousness. i ABSTRACT This paper explores glitch outside its usual confines of computation, specifically in performance, and the remediation of language. It asks whether, in a postdigital context, glitch has a revealing value that can reinstate the term ‘doppelgänger ’ as an apparition of double character. In revealing, does the digital doppelgänger extend beyond alterity, to a co- originary point, and if so, can this feedback to us materially and epistemologically, avoiding contractive binaries to retain its ambiguous essence and our inter-subjectivities? A number of discourses are examined with particular reference to information theory, the philosophies of Heidegger and Nancy, the posthumanism of Hayles, Lacan’s psychoanalysis, and to glitch itself. -

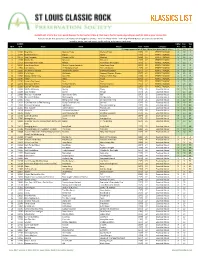

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT