Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIS Working Papers No 136 the Price Level, Relative Prices and Economic Stability: Aspects of the Interwar Debate by David Laidler* Monetary and Economic Department

BIS Working Papers No 136 The price level, relative prices and economic stability: aspects of the interwar debate by David Laidler* Monetary and Economic Department September 2003 * University of Western Ontario Abstract Recent financial instability has called into question the sufficiency of low inflation as a goal for monetary policy. This paper discusses interwar literature bearing on this question. It begins with theories of the cycle based on the quantity theory, and their policy prescription of price stability supported by lender of last resort activities in the event of crises, arguing that their neglect of fluctuations in investment was a weakness. Other approaches are then taken up, particularly Austrian theory, which stressed the banking system’s capacity to generate relative price distortions and forced saving. This theory was discredited by its association with nihilistic policy prescriptions during the Great Depression. Nevertheless, its core insights were worthwhile, and also played an important part in Robertson’s more eclectic account of the cycle. The latter, however, yielded activist policy prescriptions of a sort that were discredited in the postwar period. Whether these now need re-examination, or whether a low-inflation regime, in which the authorities stand ready to resort to vigorous monetary expansion in the aftermath of asset market problems, is adequate to maintain economic stability is still an open question. BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS. -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

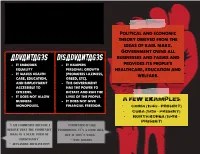

Forms of Government

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

Three Revolutions in Macroeconomics: Their Nature and Influence

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Laidler, David Working Paper Three revolutions in macroeconomics: Their nature and influence EPRI Working Paper, No. 2013-4 Provided in Cooperation with: Economic Policy Research Institute (EPRI), Department of Economics, University of Western Ontario Suggested Citation: Laidler, David (2013) : Three revolutions in macroeconomics: Their nature and influence, EPRI Working Paper, No. 2013-4, The University of Western Ontario, Economic Policy Research Institute (EPRI), London (Ontario) This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/123484 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Nber Working Paper Series David Laidler On

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DAVID LAIDLER ON MONETARISM Michael Bordo Anna J. Schwartz Working Paper 12593 http://www.nber.org/papers/w12593 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2006 This paper has been prepared for the Festschrift in Honor of David Laidler, University of Western Ontario, August 18-20, 2006. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2006 by Michael Bordo and Anna J. Schwartz. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. David Laidler on Monetarism Michael Bordo and Anna J. Schwartz NBER Working Paper No. 12593 October 2006 JEL No. E00,E50 ABSTRACT David Laidler has been a major player in the development of the monetarist tradition. As the monetarist approach lost influence on policy makers he kept defending the importance of many of its principles. In this paper we survey and assess the impact on monetary economics of Laidler's work on the demand for money and the quantity theory of money; the transmission mechanism on the link between money and nominal income; the Phillips Curve; the monetary approach to the balance of payments; and monetary policy. Michael Bordo Faculty of Economics Cambridge University Austin Robinson Building Siegwick Avenue Cambridge ENGLAND CD3, 9DD and NBER [email protected] Anna J. Schwartz NBER 365 Fifth Ave, 5th Floor New York, NY 10016-4309 and NBER [email protected] 1. -

Liberty, Property and Rationality

Liberty, Property and Rationality Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Master’s Thesis Hannu Hästbacka 13.11.2018 University of Helsinki Faculty of Arts General History Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Filosofian, historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Hannu Hästbacka Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Liberty, Property and Rationality. Concept of Freedom in Murray Rothbard’s Anarcho-capitalism Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Yleinen historia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma year 100 13.11.2018 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) on yksi keskeisimmistä modernin libertarismin taustalla olevista ajattelijoista. Rothbard pitää yksilöllistä vapautta keskeisimpänä periaatteenaan, ja yhdistää filosofiassaan klassisen liberalismin perinnettä itävaltalaiseen taloustieteeseen, teleologiseen luonnonoikeusajatteluun sekä individualistiseen anarkismiin. Hänen tavoitteenaan on kehittää puhtaaseen järkeen pohjautuva oikeusoppi, jonka pohjalta voidaan perustaa vapaiden markkinoiden ihanneyhteiskunta. Valtiota ei täten Rothbardin ihanneyhteiskunnassa ole, vaan vastuu yksilöllisten luonnonoikeuksien toteutumisesta on kokonaan yksilöllä itsellään. Tutkin työssäni vapauden käsitettä Rothbardin anarko-kapitalistisessa filosofiassa. Selvitän ja analysoin Rothbardin ajattelun keskeisimpiä elementtejä niiden filosofisissa, -

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series The Search for Value: Measuring the Company's Cost of Capital Michael C. Ehrhardt Managing Pension Plans: A Comprehensive Guide to Improving Plan Performance Dennis E. Logue and Jack S. Rader Efficient Asset Management: A Practical Guide to Stock Portfolio Optimization and Asset Allocation Richard O. Michaud Real Options: Managing Strategic Investment in an Uncertain World Martha Amram and Nalin Kulatilaka Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin Dividend Policy: Its Impact on Form Value Ronald C. Lease, Kose John, Avner Kalay, Uri Loewenstein, and Oded H. Sarig Value Based Management: The Corporate Response to Shareholder Revolution John D. Martin and J. William Petty Debt Management: A Practitioner's Guide John D. Finnerty and Douglas R. Emery Real Estate Investment Trusts: Structure, Performance, and Investment Opportunities Su Han Chan, John Erickson, and Ko Wang Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners Larry Harris Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin 2002 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. -

Free to Choose

June 9, 2005 COMMENTARY Free to Choose By MILTON FRIEDMAN June 9, 2005; Page A16 Little did I know when I published an article in 1955 on "The Role of Government in Education" that it would lead to my becoming an activist for a major reform in the organization of schooling, and indeed that my wife and I would be led to establish a foundation to promote parental choice. The original article was not a reaction to a perceived deficiency in schooling. The quality of schooling in the United States then was far better than it is now, and both my wife and I were satisfied with the public schools we had attended. My interest was in the philosophy of a free society. Education was the area that I happened to write on early. I then went on to consider other areas as well. The end result was "Capitalism and Freedom," published seven years later with the education article as one chapter. With respect to education, I pointed out that government was playing three major roles: (1) legislating compulsory schooling, (2) financing schooling, (3) administering schools. I concluded that there was some justification for compulsory schooling and the financing of schooling, but "the actual administration of educational institutions by the government, the 'nationalization,' as it were, of the bulk of the 'education industry' is much more difficult to justify on [free market] or, so far as I can see, on any other grounds." Yet finance and administration "could readily be separated. Governments could require a minimum of schooling financed by giving the parents vouchers redeemable for a given sum per child per year to be spent on purely educational services. -

CURRICULUM VITAE (September 2020)

1 CURRICULUM VITAE (September 2020) NAME: David E.W. Laidler NATIONALITY: Canadian (also U.K.) DATE OF BIRTH: 12 August 1938 MARITAL STATUS: Married, one daughter HOME ADDRESS: 45 - 124 North Centre Road London, Ontario Canada N5X 4R3 Telephone: (519) 673-3014 FAX: (519) 661-3666 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION AND DEGREES HELD: Tynemouth School, Tynemouth, Northumberland, England, GCE 'O' Level 1953, 'A' Level, 1955, 'S' Level, 1956 London School of Economics, B.Sc. Econ. (Economics Analytic and Descriptive) 1st Class Honours, 1959 University of Syracuse, M.A. (Economics), 1960 University of Chicago, Ph.D. (Economics), 1964 University of Manchester, M.A. 1973 (not an "earned" degree) University of Western Ontario, LL.D.(h.c.) 2016 SCHOLARSHIPS, FELLOWSHIPS AND ACADEMIC HONOURS: 1956-1959 State Scholarship 1959-1960 University of Syracuse: University Fellowship 1960-1961 University of Chicago: Edward Hillman Fellowship 1962-1963 University of Chicago: Earhart Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship 1972 British Association for the Advancement of Science, Lister Lecture, to be given by a distinguished contributor to the Social Sciences under 35 years of age 1982 - Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada 1987-1988 President, Canadian Economics Association/Association Canadienne d'Economique 1988-1989 Faculty of Social Science Research Professor, University of Western Ontario 1994 Douglas Purvis Memorial Prize, awarded by the Canadian Economics Association for a significant work on Canadian Economic Policy (joint recipient with W.B.P. Robson) 1999 Hellmuth Prize for distinguished research in the Humanities and Social Sciences by a member of the faculty of the University of Western Ontario 2004-2005 Donner Prize for the best book of the year on Canadian public policy. -

Passive Money, Active Money, and Monetary Policy

Passive Money, Active Money, and Monetary Policy David Laidler, Visiting Economist • The role of money in the transmission of or eight years, an inflation target, jointly set by monetary policy is still controversial. Some the Bank of Canada and the federal govern- regard it as reacting passively to changes in ment, has provided the anchor for Canada’s F monetary policy. For a period 20 times as long, prices, output, and interest rates; others see it the Quantity Theory of Money has provided econo- playing an active role in bringing about mists with a framework for analyzing the influence changes in these variables. of the supply of money on the inflation rate. The Bank of Canada regularly comments on the behaviour of • Empirical evidence favours an active the narrow M1 and the broader M2 aggregates in its interpretation of money’s role in the Canadian Monetary Policy Report and in the Bank of Canada economy, particularly in the case of narrow, Review, but the Quarterly Projection Model (QPM), transactions-oriented aggregates. which currently provides the analytic background against which the Bank’s policies are designed, • Institutional changes can, and do, create includes no monetary aggregate.1 Even so, there is a instabilities in the demand functions for strong case to be made that the money supply is not narrow aggregates, which undermine their only the key long-run determinant of inflation in the Canadian economy but is also an important variable usefulness as formal policy targets. in the transmission mechanism through which policy • There is, nevertheless, a strong case for the actions affect the price level, and, in the shorter run, income and employment as well. -

Brexit and the Economics of Populism Ditchley Park, Oxfordshire 4-5 November 2016

Conference report: Brexit and the economics of populism Ditchley Park, Oxfordshire 4-5 November 2016 #CERditchley Brexit and the economics of populism Ditchley Park Oxfordshire 4-5 November 2016 Executive summary November’s conference brought together 50 leading economists and commentators to consider Brexit and the economics of populism. Was Britain’s vote to leave the EU the first rebellion in a developed country against globalisation? Was further globalisation of trade and finance compatible with political stability? To what extent should we blame the macroeconomic policy response to the financial and euro crises for rising populism? Did we need stronger institutions to regulate, stabilise and legitimise markets? Did we need more income redistribution to counter inequality, more investment, and stronger action against rent-seeking? Could governments counter anti-immigrant feeling by employing the right mix of economic and social policies? Or could immigration be limited without damaging side-effects? The participants largely agreed that globalisation had not been the driving force behind the Brexit vote. Rising inequality and economic insecurity had been factors, but reflected the deregulation of labour and financial markets, technological change and tax and housing policies, more than globalisation itself. Social and cultural factors had also played a major role in the vote. The relationship between economic wellbeing and backing for populists was loose. Brexit supporters were much older than average, had not been affected economically by immigration or suffered disproportionately from the financial crisis. Support for central bank independence was fraying, there was now broad-based support among economists for government intervention to bolster demand, and an acceptance that financial stability required the authorities to actively regulate markets.