Using Artifacts to Study the Past Early Evidence for John Day Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Resource Use and Disturbance in Riverine Basins Of

Robert C. Wissmar,'Jeanetle E, Smith,'Bruce A. Mclntosh,,HiramW. Li,. Gordon H. Reeves.and James R. Sedell' A Historyof ResourceUse and Disturbancein RiverineBasins of Eastern Oregonand Washington(Early 1800s-1990s) Abstract Rj\( r n.rsr, rr Cds.lde u rl|alrlo|ogicso1c\|n|Slhalshrpedthepresent'dailalrlsraprlsrn l.ii\||sl'rn|e!nroddriParianecosrstctnsllllldr'li!l's|oi'L|!7jrgand anllril,rri!ndl.es.|edi1iiculttonanagebtaull]itl]cis|no{nlboU|holtheseecosrelnsfu dele|pprorrrlrrrr's|ortrl.rtingthesrInptonlsofd {ith pluns lbr resoliirg t h$itatscontinuetodeclile'Altlrrratjrrl|r.nrrrbusin\!jelnan!genentst' hoPel'orinlp|ornlgthee.os}sl.jn]h;odjl('tsi|\anrlpopuationlelelsoffshaldirj1d]jn''PrioIili(jsi|r(|ullc|hePf Nrtersheds (e.g.. roarll+: a Introduction to$,ards"natur-al conditions" that nleetLhe hislr)ri- tal requirernentsoffish and t'ildlile. Some rnajor As a resull of PresidentClirrton's ! orcst Summit qucstions that need to be ansrererl arc. "How hale in PortlandOrcgon cluring Spring 19913.consider- hisloricalccosvstcms iunctionecl and ho* nale ntr ablc attention is heing licusecl on thc inllucnccs man a( lions changcd them'/'' of hre-t .rn,l,'tlrr'r r, -urrrr. mJnlrepmpntl,f;r.ti, c- orr lhe health of l'acific No|th$'esLecosystems. This drrcumcntrcvict's the environmentalhis- l\{anagcrncnt recornmendations of an inLer-agr:ncv torr ol theinfl.r-n, '-,,f h',rrrunJ, ti\'ti, - in cJ-l tcanrol scicntistspoint to the urgenLneed frrr irn- ern O|cgon and Waslington over lhe pasl l\\o in ccosvstemm:uagement (Foresl lic- lr|1^emcnts centurie-s.The -

Oregon and Manifest Destiny Americans Began to Settle All Over the Oregon Country in the 1830S

NAME _____________________________________________ DATE __________________ CLASS ____________ Manifest Destiny Lesson 1 The Oregon Country ESSENTIAL QUESTION Terms to Know joint occupation people from two countries living How does geography influence the way in the same region people live? mountain man person who lived in the Rocky Mountains and made his living by trapping animals GUIDING QUESTIONS for their fur 1. Why did Americans want to control the emigrants people who leave their country Oregon Country? prairie schooner cloth-covered wagon that was 2. What is Manifest Destiny? used by pioneers to travel West in the mid-1800s Manifest Destiny the idea that the United States was meant to spread freedom from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean Where in the world? 54°40'N Alaska Claimed by U.S. and Mexico (Russia) Oregon Trail BRITISH OREGON 49°N TERRITORY Bo undary (1846) COUNTRY N E W S UNITED STATES MEXICO PACIFIC OCEAN ATLANTIC OCEAN When did it happen? DOPA (Discovering our Past - American History) RESG Chapter1815 13 1825 1835 1845 1855 Map Title: Oregon Country, 1846 File Name: C12-05A-NGS-877712_A.ai Map Size: 39p6 x 26p0 Date/Proof: March 22, 2011 - 3rd Proof 2016 Font Conversions: February 26, 2015 1819 Adams- 1846 U.S. and Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission is granted to reproduce for classroom use. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission 1824 Russia 1836 Whitmans Onís Treaty gives up claim to arrive in Oregon Britain agree to Oregon 49˚N as border 1840s Americans of Oregon begin the “great migration” to Oregon 165 NAME _____________________________________________ DATE __________________ CLASS ____________ Manifest Destiny Lesson 1 The Oregon Country, Continued Rivalry in the Northwest The Oregon Country covered much more land than today’s state Mark of Oregon. -

Wyoming SCORP Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2014 - 2019 Wyoming Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2014-2019

Wyoming SCORP Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2014 - 2019 Wyoming Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2014-2019 The 2014-2019 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan was prepared by the Planning and Grants Section within Wyoming’s Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources, Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails. Updates to the trails chapter were completed by the Trails Section within the Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department provided the wetlands chapter. The preparation of this plan was financed through a planning grant from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, under the provision of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 (Public Law 88-578, as amended). For additional information contact: Wyoming Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails 2301 Central Avenue, Barrett Building Cheyenne, WY 82002 (307) 777-6323 Wyoming SCORP document available online at www.wyoparks.state.wy.us. Table of Contents Chapter 1 • Introduction ................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 2 • Description of State ............................................................................. 11 Chapter 3 • Recreation Facilities and Needs .................................................... 29 Chapter 4 • Trails ............................................................................................................ -

Download the Report

Oregon Cultural Trust fy2011 annual report fy2011 annual report 1 Contents Oregon Cultural Trust fy2011 annual report 4 Funds: fy2011 permanent fund, revenue and expenditures Cover photos, 6–7 A network of cultural coalitions fosters cultural participation clockwise from top left: Dancer Jonathan Krebs of BodyVox Dance; Vital collaborators – five statewide cultural agencies artist Scott Wayne 8–9 Indiana’s Horse Project on the streets of Portland; the Museum of 10–16 Cultural Development Grants Contemporary Craft, Portland; the historic Astoria Column. Oregonians drive culture Photographs by 19 Tatiana Wills. 20–39 Over 11,000 individuals contributed to the Trust in fy2011 oregon cultural trust board of directors Norm Smith, Chair, Roseburg Lyn Hennion, Vice Chair, Jacksonville Walter Frankel, Secretary/Treasurer, Corvallis Pamela Hulse Andrews, Bend Kathy Deggendorfer, Sisters Nick Fish, Portland Jon Kruse, Portland Heidi McBride, Portland Bob Speltz, Portland John Tess, Portland Lee Weinstein, The Dalles Rep. Margaret Doherty, House District 35, Tigard Senator Jackie Dingfelder, Senate District 23, Portland special advisors Howard Lavine, Portland Charlie Walker, Neskowin Virginia Willard, Portland 2 oregon cultural trust December 2011 To the supporters and partners of the Oregon Cultural Trust: Culture continues to make a difference in Oregon – activating communities, simulating the economy and inspiring us. The Cultural Trust is an important statewide partner to Oregon’s cultural groups, artists and scholars, and cultural coalitions in every county of our vast state. We are pleased to share a summary of our Fiscal Year 2011 (July 1, 2010 – June 30, 2011) activity – full of accomplishment. The Cultural Trust’s work is possible only with your support and we are pleased to report on your investments in Oregon culture. -

Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians Cynthia J. Manning The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Manning, Cynthia J., "Ethnohistory of the Kootenai Indians" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5855. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5855 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished m a n u s c r ip t in w h ic h c o p y r ig h t su b s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s c o n ten ts must be a ppro ved BY THE AUTHOR. MANSFIELD L ib r a r y Un iv e r s it y of Montana D a te : 1 9 8 3 AN ETHNOHISTORY OF THE KOOTENAI INDIANS By Cynthia J. Manning B.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1978 Presented in partial fu lfillm en t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Approved by: Chair, Board of Examiners Fan, Graduate Sch __________^ ^ c Z 3 ^ ^ 3 Date UMI Number: EP36656 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

A Free Emigrant Road 1853: Elijah Elliott's Wagons

Meek’s Cutoff: 1845 Things were taking much longer than expected, and their Macy, Diamond and J. Clark were wounded by musket supplies were running low. balls and four horses were killed by arrows. The Viewers In 1845 Stephen Hall Meek was chosen as Pilot of the 1845 lost their notes, provisions and their geological specimens. By the time the Train reached the north shores of Harney emigration. Meek was a fur trapper who had traveled all As a result, they did not see Meek’s road from present-day Lake, some of the men decided they wanted to drive due over the West, in particular Oregon and California. But Vale into the basin, but rode directly north to find the west, and find a pass where they could cross the Cascade after a few weeks the independently-minded ‘45ers decided Oregon Trail along Burnt River. Mountains. Meek was no longer in control. When they no Pilot was necessary – they had, after all, ruts to follow - Presented by Luper Cemetery Inc. arrived at Silver River, Meek advised them to turn north, so it was not long before everyone was doing their own Daniel Owen and follow the creek to Crooked River, but they ignored his thing. Great-Grandson of Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Owen advice. So the Train headed west until they became bogged down at the “Lost Hollow,” on the north side of Wagontire Mountain. Here they became stranded, because no water could be found ahead, in spite of the many scouts searching. Meek was not familiar with this part of Oregon, although he knew it was a very dry region. -

Etienne Lucier

Etienne Lucier Readers should feel free to use information from the website, however credit must be given to this site and to the author of the individual articles. By Ella Strom Etienne Lucier was born in St. Edouard, District of Montreal, Canada, in 1793 and died on the French Prairie in Oregon, United States in 1853.1 This early pioneer to the Willamette Valley was one of the men who helped to form the early Oregon society and government. Etienne Lucier joined the Wilson Price Hunt overland contingent of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company in 1810.2 3 After the Pacific Fur Company was dissolved during the War of 1812,4 he entered the service of the North West Company and, finally, ended up being a brigade leader for the Hudson’s Bay Company.5 For a short time in 1827, he lived on what would be come known as East Portland. He helped several noted pioneers establish themselves in the northern Willamette Valley by building three cabins in Oregon City for Dr. John McLoughlin and a home at Chemaway for Joseph Gervais.6 Also as early as 1827, Lucier may have had a temporary cabin on a land claim which was adjacent to the Willamette Fur Post in the Champoeg area. However, it is clear that by 1829 Lucier had a permanent cabin near Champoeg.7 F.X. Matthieu, a man who would be instrumental in determining Oregon’s future as an American colony, arrived on the Willamette in 1842, “ragged, barefoot, and hungry” and Lucier gave him shelter for two years.8 Matthieu and Lucier were key votes in favor of the organization of the provisional government under American rule in the May 1843 vote at Champoeg. -

Ual Report of the Trustees

THE CENTRAL PARK, NEW YORK CITY. (77th Street and 8th Avenue.) ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES AND - LIST OF MEMBERS FOR THE- YEnAR 1886=7. PRINTED FOR THE MUSEUM. THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, CENTRAL PARK, NEW YORK CITY. (77th Street and 8th Avenue.) ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES AND LIST OF MEMBERS FOR THE YEsAR 1886-7. NEW YORK: PRINTED FOR THE MUSEUM. 1887. &4iSox-a-E.t-t ;-S60-. buff. 0. kAAnTIN. ill JOHX ton -,q..Jwm9 BOARD OF TRUSTEES. MORRIS K. JESUP. ABRAM S. HEWITT. BENJAMIN H. FIELD. CHARLES LANIER. ADRIAN ISELIN. HUGH AUCHINCLOSS. J. PIERPONT MORGAN. OLIVER HARRIMAN. D. JACKSON STEWARD. C. VANDERBILT. JOSEPH H. CHOATE. D. 0. MILLS. PERCY R. PYNE. CHAS. G. LANDON. JOHN B. TREVOR. H. R. BISHOP. JAMES M. CONSTABLE. ALBERT S. BICKMORE. WILLIAM E. DODGE. THEODORE ROOSEVELT. JOSEPH W. DREXEL. OSWALD OTTENDORFER. ANDREW H. GREEN. J. HAMPDEN ROBB. OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES FOR I887. President. MORRIS K. JESUP. Vice-Presidents. D. JACKSON STEWARD. JAMES M. CONSTABLE. Secretary. ALBERT S. BICKMORE. Treasurer. J. PIERPONT MORGAN. Executive Committee. JAMES M. CONSTABLE, Chairman. D. JACKSON STEWARD. JOSEPH W. DREXEL. H. R. BISHOP. THEODORE ROOSEVELT. The President and Secretary, ex-ojficio. Auditing Committee. CHARLES LANIER. ADRIAN ISELIN. C. VANDERBILT. Finance Committee. J. PIERPONT MORGAN. D. 0. MILLS. JOHN B. TREVOR. PROF. ALBERT S. BICKMORE, Curator of the Ethnological Department, and in charge of the Department of Public Instruction. PROF. R. P. WHITFIELD, Curator of the Geological, Mineralogical and Conchological Department. L. P. GRATACAP, Assistant Curator of the Geological Department. J. A. ALLEN, Curator of the Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy. -

Register Cliff AND/OR HISTORIC

Form 10-300 (Dec. 1968) Wyoming COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Platte INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) lililii Register Cliff AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET ANDNUMBER: NW%, NW%, Section 7; T. 26 N., R. 6J5.W. CITY OR TOWN: Guernsey COUNTY: Wyoming 49 Platte 031 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Z 'Public District CD Building CD D Public Acquisition: Occupied CD Yes: O Site [X| Structure Private a In Process [~~1 Unoccupied B Restricted CD Both Being Considered I I Unrestricted |y] Object Preservation work in progress |~j No: D u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) ID Agricultural [ | Government d) Park Transportation | | Comments I f Commercial CD Industrial CD Private Residence CD Other (Specify) C7] _____ Educational CD Military CD Religious Ranch Property Entertainment | | Museum CD Scientific State Historic Site OWNERS NAME: State of Wyoming, administered by the Wyoming Recreation Commission LJJ STREET AND NUMBER: W 604 East 25th Street to CITY OR TOWN: Cheyenne Wyoming 49 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Wyoming Recreation Commission STREET AND NUMBER: 604 East 25th Street CITY OR TOWN: Cheyenne Wyoming 49 APPROXIMATE ACREAGE OF NOMINATED PROPERTY: TITLE OF SURVEY: Evaluation and Survey of Historic Sites in Wyoming DATE OF SURVEY: 1963 Federal State CD County CD Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: National Park Service STREET AND NUMBER: Midwest Regional Office, Department of Interior CITY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 08 : :vx :: •••:•' :•. ' >. •'• ' '••'• . :-: :•: .•:• x '.x..;:/ :" .'.:.>- • i :"S:S'':xS:i;S:5;::::BS m. '&•• ?&*-ti':W$wS&3^$$$s (Check One) CONDITION Excellent Q Good [x Fair Q Deteriorated Q Ruins a Unexposed a (Check One) (Check One) INTEGRITY Altered D Unaltered ^] Moved | | Original Site [^j DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Register Cliff consists of a soft, chalky, limestone precipice rising over 100 feet above the valley floor of the North Platte River. -

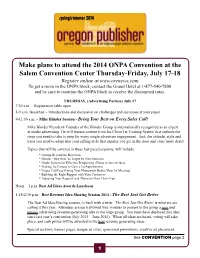

Make Plans to Attend the 2014 ONPA Convention at the Salem

spring/summer 2014 Make plans to attend the 2014 ONPA Convention at the Salem Convention Center Thursday-Friday, July 17-18 Register online at www.orenews.com To get a room in the ONPA block, contact the Grand Hotel at 1-877-540-7800 and be sure to mention the ONPA block to receive the discounted rates. THURSDAY, (Advertising Portion) July 17 7:30 a.m. – Registration table open 8-9 a.m. Breakfast – Introductions and discussion on challenges and successes at your paper 9-11:30 a.m. – Mike Blinder Session - Being Your Best on Every Sales Call! Mike Blinder President/ Founder of the Blinder Group is internationally recognized as an expert at media advertising. He will feature content from his Client 1st Training System that outlines the steps you need to take to prep for every single advertiser engagement. And, the attitude, style and traits you need to adapt into your selling style that ensures you get in the door and close more deals! Topics that will be covered in these fast paced sessions, will include: * Getting Beyond the Rejection * Blinder “Best Bets” to Target for New Business * Goals/ System for Effective Prospecting (Phone or face-to-face) * Making 1st Contact to Gain a 1st Appointment * Proper Call Prep (Doing Your Homework Before Your 1st Meeting) * Building the Right Rapport with Your Customers * Adjusting Your Rapport (and Theirs) to Gain Their Trust Noon – 1 p.m. Best Ad Ideas Awards Luncheon 1:15-2:30 p.m. Best Revenue Idea Sharing Session 2014 - The Best Just Got Better The Best Ad Idea Sharing session, is back with a twist. -

Albert Gallatin: Champion of American Democracy

Albert Gallatin: Champion of American Democracy Friendship Hill National Historic Site Education Guide Post-Visit Activities Post-Visit Activities Post-Visit Activity #1 – Comic Strip Directions: Have students look over several comic strips in the newspaper and look up the definition of the word cartoon. Have them draw or illustrate their own comic strip about Albert Gallatin. The students can base their comic strip on their visit to Friendship Hill, and what they have read and learned about Albert Gallatin. Post-Visit Activity #2 – Headline News Directions: After studying about the Lewis and Clark expedition and Albert Gallatin, have the students make up headlines about the event. Write several of the headlines on the classroom board. Have the students pick a headline and write a short newspaper account about it. The students may read their news articles to the class. Post-Visit Activity #3 – Whiskey Rebellion Flag Directions: The angry farmers in 1794 designed a Whiskey Rebellion flag with symbols that expressed their feelings. Have the students construct or draw their own flags with symbols, designs and logos that express their feelings. Display the flags in the classroom. Have the students examine each other’s flags and see if they can tell what the flags mean. Post-Visit Activity #4 – Artist Poster Directions: Have the students design a poster of young Albert Gallatin using the objects that symbolize his early involvement in Southwestern Pennsylvania and the United States government. Post-Visit Activity #5 – Albert Gallatin Bulletin Board Directions: Throughout his 68 years of public service Albert Gallatin became friends with many influential people. -

Astoria Adapted and Directed by Chris Coleman

Astoria Adapted and directed by Chris Coleman Based on the book ASTORIA: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Je erson’s Lost Pacific Empire, A Story of Wealth, Ambition, The Guide and Survival by Peter Stark A Theatergoer’s Resource Education & Community Programs Staff Kelsey Tyler Education & Community Programs Director Peter Stark -Click Here- Clara-Liis Hillier Education & Community Programs Associate Eric Werner Education & Community Programs Coordinator The Astor Expedition Matthew B. Zrebski -Click Here- Resident Teaching Artist Resource Guide Contributors Benjamin Fainstein John Jacob Astor Literary Manager and Dramaturg -Click Here- Mikey Mann Graphic Designer The World of Astoria -Click Here- PCS’s 2016–17 Education & Community Programs are generously supported by: Cast and Creative Team -Click Here- Further Research -Click Here- PCS’s education programs are supported in part by a grant from the Oregon Arts Commission and the National Endowment for the Arts. Michael E. Menashe Mentor Graphics Foundation Herbert A. Templeton Foundation H. W. Irwin and D. C. H. Irwin Foundation Autzen Foundation and other generous donors. TONQUIN PARTY Navy Men Captain Jonathan Thorn 1st Mate Ebenezer Fox Aiken (played by Ben Rosenblatt) (played by Chris Murray) (played by Brandon Contreras) Coles Winton Aymes (played by Jeremy Aggers) (played by Michael Morrow Hammack) (played by Leif Norby) Canadian & Scottish Partners Duncan Macdougall Alexander McKay David Stuart (played by Gavin Hoffman) (played by Christopher Hirsh) (played by F. Tyler Burnet) Agnus Robert Stuart (played by Christopher Salazar) (played by Jeremy Aggers) Others Gabriel Franchere Alexander Ross (played by Ben Newman) (played by Nick Ferrucci) OVERLAND PARTY Leaders Wilson Price Hunt Ramsay Crooks Donald MacKenzie (played by Shawn Fagan) (played by Benjamin Tissell) (played by Jeremy Aggers) Company John Bradbury John Reed John Day (played by F.