SAJRP Topics Vol. 2 No. 1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLCA Library of Congress Research Initiative

https://glca.org/ GLCA Library of Congress Research Initiative In a partnership with the Library of Congress, the Great Lakes Colleges Association invites proposals from faculty of its member colleges – and from the extended network of institutions participating in the Global Liberal Arts Alliance – to participate in a faculty/student collaborative research program drawing on the resources of the world’s most comprehensive research library. The program, called the GLCA-Library of Congress Faculty-Student Research Initiative, offers a unique opportunity for undergraduate students and faculty mentors to receive direct support for scholarly research from designated Library of Congress research librarians – a level of research support generally accorded to advanced scholars. To access the complete Request for Proposals for Summer of 2019, click here. Previous Projects and their Faculty Leaders 2012 “Ties that Bind? Education in the Early American Republic.” Kabria Baumgartner, The College of Wooster. “Development of the Concept of the “Separation of Church and State” as a Legal Doctrine in the United States.” T. Jeremy Gunn, Al Akhawayn University. 2013 “Politics of Memory in the Slovak-Hungarian Relations.” Dagmar Kusa, Bratislava International School of Liberal Arts. “Political History of Homelessness in America.” Virginia Parish Beard, Hope College. “Texts for Teens Over Time: An Exploration of the Various Historical Constructions of Adolescence and its Effects on Adolescents’ Literacy Sponsorship.” Deborah Vriend Van Duinen, Hope College. 2014 Cultural Origins of Wall Street’s Rise to Power, Ryan Murphy, Earlham College. The History of Jewry in the 20th Century and their Evolving Relationship to Zionism in Israel.” Michael Reimer, American University in Cairo. -

JOURNAL of PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH in SOCIAL SCIENCES Prof

JPRSS, Vol. 1, No. 1, July 2014 JOURNAL OF PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES Prof. Dr. Naudir Bakht Editor In-Chief Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences provides a forum for discussion on issues and problems primarily relating to Pakistan. We welcome contributions by researchers, administrators, policy makers and all others interested in promoting better understanding of Pakistan affairs. Published in Summer and Winter every Year, articles appearing in the journal are recognized by Higher Education Commission for promotion and appointments and are indexed and abstracted in international Bibliography of Social Sciences, London and International Politics Science Abstracts, Paris. The journal is also available online at http://www.mul.edu.pk/crd Disclaimer Views expressed in the Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences do not reflect the views of the Centre or the Editors. Responsibility for the accuracy of facts and for the opinions expressed rests solely with the authors. Subscription Rates Pakistan Annual Rs. 400.00 Single Copy Rs. 250.00 Foreign Annual Rs. U.S. $ 50.00 Single Copy Rs. U.S. $ 30.00 Correspondence All correspondence should be directed to the Director/Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences, Minhaj University, Hamdard Chowk, Township, Lahore - Pakistan. MINHAJ UNIVERSITY LAHORE 2014 © Copyright by All rights reserved. The material printed in this journal may not be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the Director. Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences JPRSS, Vol. 1, No. 1, July 2014 JOURNAL OF PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES Vol. 1, No.1 Summer 2014 Centre for Research and Development Faculty of Social Sciences Contact: +92-42-35145621-6, Ext. -

JPRSS, Vol. 03, No. 01, Summer 2016 Journal of Professional Research

JPRSS, Vol. 03, No. 01, Summer 2016 JOURNAL OF PROFESSIONAL RESEARCH IN SOCIAL SCIENCES Prof. Dr. Naudir Bakht Editor In-Chief It is a matter of great honor and pleasure for me and my team that by the fabulous and continuous cooperation of our distinguished National/International Contributors/ Delegates, we are able to present our Research Journal, “Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences, Vol. 03, No. 01, Summer 2016 . The Centre has made every effort to improve the quality and standard of the paper, printing and of the matter. I feel honored to acknowledge your generous appreciation, input and response for the improvement of the Journal. I offer my special thanks to: 1. Prof. Dr. Neelambar Hatti, Professor Emeritus, Department of Economic History, Lund University, Sweden 2. Ms. Bushra Almas Jaswal Chief Librarian & Associate Professor Ewing Memorial Library Forman Christian College 3. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui Vice Chancellor Allama Iqbal Open University Islamabad 4. Prof. Dr. Javed Haider Syed Chairman Department of History & Pakistan Studies University of Gujrat Journal of Professional Research in Social Sciences JPRSS, Vol. 03, No. 01, Summer 2016 5. Engr. Prof. Dr. Sarfraz Hussain, TI(M), SI(M) Vice Chancellor DHA Sufa University DHA, Karachi 6. Prof. Dr. Najeed Haider Registrar Ghazi University, D.G Khan 7. Muhammad Yousaf Dy. Registrar City University Peshawar 8. Dr. Bashir Goraya Vice Chancellor Al-Khair University (AJK) 9. Safia Imtiaz Librarian Commecs Institute of Business and Emerging Science 10. Prof. Dr. Dost Ali Khowaja Academic Coordinator, FOE Dawood University of Engineering and Technology 11. Prof. Dr. M. Shamsuddin Honorary Advisor to VC University of Karachi 12. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

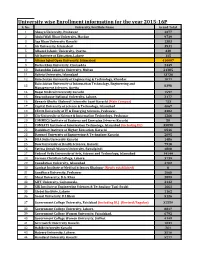

University Wise Enrollment Information for the Year 2015-16P S

University wise Enrollment information for the year 2015-16P S. No. University/Institute Name Grand Total 1 Abasyn University, Peshawar 4377 2 Abdul Wali Khan University, Mardan 9739 3 Aga Khan University Karachi 1383 4 Air University, Islamabad 3531 5 Alhamd Islamic University, Quetta. 338 6 Ali Institute of Education, Lahore 115 8 Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad 416607 9 Bacha Khan University, Charsadda 2449 10 Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan 21385 11 Bahria University, Islamabad 13736 12 Balochistan University of Engineering & Technology, Khuzdar 1071 Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and 13 8398 Management Sciences, Quetta 14 Baqai Medical University Karachi 1597 15 Beaconhouse National University, Lahore. 2177 16 Benazir Bhutto Shaheed University Lyari Karachi (Main Campus) 753 17 Capital University of Science & Technology, Islamabad 4067 18 CECOS University of IT & Emerging Sciences, Peshawar. 3382 19 City University of Science & Information Technology, Peshawar 1266 20 COMMECS Institute of Business and Emerging Sciences Karachi 50 21 COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad (including DL) 35890 22 Dadabhoy Institute of Higher Education, Karachi 6546 23 Dawood University of Engineering & Technology Karachi 2095 24 DHA Suffa University Karachi 1486 25 Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi 7918 26 Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi 4808 27 Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science and Technology, Islamabad 14144 28 Forman Christian College, Lahore. 3739 29 Foundation University, Islamabad 4702 30 Gambat Institute of Medical Sciences Khairpur (Newly established) 0 31 Gandhara University, Peshawar 1068 32 Ghazi University, D.G. Khan 2899 33 GIFT University, Gujranwala. 2132 34 GIK Institute of Engineering Sciences & Technology Topi-Swabi 1661 35 Global Institute, Lahore 1162 36 Gomal University, D.I.Khan 5126 37 Government College University, Faislabad (including DL) (Revised/Regular) 32559 38 Government College University, Lahore. -

CV of Prof. Dr. Amra Raza

PROF. DR. AMRA RAZA Chairperson, Professor Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore E-mail: [email protected] Contact: 99231168 QUALIFICATIONS: 2008-Institution University of the Punjab, Lahore. Title of Research Thesis “Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Ph.D Hashmi‘s Poetry First Ph.D produced by the Department of English, University of the Punjab. 2001-Institution University of the Punjab, Lahore M.Phil Title of Research Thesis “Self Conscious Surveillance Strategies in Derek Walcott‘s Poetry (1948-84)” M.A. English 1989-Institution The University of Karachi Literature Merit First Class first position 1991-Institution The University of Karachi M.A. Linguistics Merit First Class First Position Research Thesis entitled ―The Feasibility of Establishing a Self Access Centre at Karachi University on the basis of the Self Access Centre at Agha Khan University School of Nursing, Karachi B.A. 1985-86 Institution St. Joseph’s College for Women, Karachi Merit First Division 1982-Institution St. Joseph’s College for Women, Karachi F.A. Merit First Division 1980-Institution: St. Joseph’s Convent School Karachi Matriculation Merit First Class Second Position (Humanities/Arts), Board of Secondary Education, Karachi. 1. American School – Bad Godesberg, Bonn, German Primary 2. British Embassy Preparatory School, Bonn, Germany Education 3. Nicolaus Cusanus Gymnasium, Bonn, Germany 1. National Jane Townsend Poetry Prize United States Cultural Centre, Karachi (1990) 2. Matric Certificate of Merit (General Group) Board of Secondary Education, Karachi First Class 2nd Position (1980) 3. First Class First Position (M.A. English Literature). Merit Certificate The University of Karachi (1989) 4. -

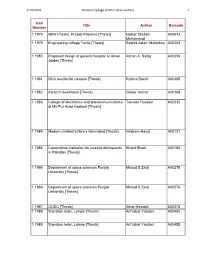

National Colege of Art Thesis List.Xlsx

4/16/2010 National College of Arts Library‐Lahore 1 Call Title Author Barcode Number 1 1975 MPA's hostel, Punjab Province [Thesis] Qaiser Ghulam A00573 Muhammad 1 1979 Engineering college Taxila [Thesis] Rashid Aslam Makhdum A00353 1 1980 Proposed design of general hospital at Aman Adnan A. Sadiq A00359 Jordan [Thesis] 1 1981 NCA residential campus [Thesis] Robina Bashir A00365 1 1982 Karachi Gymkhana [Thesis] Qaiser Ashrat A00368 1 1983 College of electronics and telecommunications Tanveer Hussain A00330 at Mir Pur Azad Kashmir [Thesis] 1 1984 Modern children's library Islamabad [Thesis] Nadeem Hayat A00121 1 1985 Correctional institution for juvenile delinquents Khalid Bhatti A00180 in Paksitan [Thesis] 1 1986 Department of space sciences Punjab Masud S Zaidi A00275 University [Thesis] 1 1986 Department of space sciences Punjab Masud S Zaidi A00276 University [Thesis] 1 1987 OGDC [Thesis] Athar Hussain A00375 1 1988 Sheraton hotel, Lahore [Thesis] Arif Iqbal Yazdani A00454 1 1988 Sheraton hotel, Lahore [Thesis] Arif Iqbal Yazdani A00455 4/16/2010 National College of Arts Library‐Lahore 2 1 1989 Engineering college Multan [Thesis] Razi-ud-Din A00398 1 1990 Islamabad hospital [Thesis] Nasir Iqbal A00480 1 1990 Islamabad hospital [Thesis] Nasir Iqbal A00492 1 1992 International Islamic University Islamabad Muhammad Javed A00584 [Thesis] 1 1994 Islamabad railway terminal: Golra junction Farah Farooq A00608 [Thesis] 1 1995 Community Facilities for Real People: Filling Ayla Musharraf A00619 Doxiadus Blanks [Thesis] 1 1995 Community Facilities -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Prof. Kanwal Ameen (PhD) Vice Chancellor, University of Home Economics Lahore [email protected] -------------------------------------------------- Former: University of the Punjab (PU), Lahore-Pakistan. Director, Directorate of External Linkages (July 2018- May 2019), Chairperson, Department of Information Management (May 2009- May 2018) Chair, Doctoral Program Coordination Committee, PU (2013-2017) Chief Editor, Pakistan Journal of Information Management & Libraries (2009-2018) Founding Chair, South Asia Chapter, ASIS&T (Association for Information Science & Technology, USA; 2018) Professor/Scholar in Residence, University of Tsukuba, Japan (2013) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kanwal_Ameen https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=ZhuLbeYAAAAJ&hl=en https://pu-pk1.academia.edu/ProfDrKanwalAmeen; https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kanwal_Ameen https://pk.linkedin.com/in/kanwal-ameen-ph-d-761b9b15 Awards and Scholarships National ● Women Excellence Award 2020. UN Women Pakistan, PPIF, Govt. of Punjab ● Indigenous Post-Doctoral Supervision Award (2018-2019), Punjab Higher Education Commission (PHEC) ● Best Paper Awards in 2015/16 and 2017, Pakistan Higher Education Commission (HEC) ● Best Teacher Award 2010, HEC ● Best Teacher Awards, University of the Punjab ● Lifetime Academic Achievements Award 2009, Pakistan Library Association, ● HEC, PHEC, PU Travel grants to present papers at international conferences. International ● James Cretsos Leadership Award, 2019, Association of Information Science &Technology, (ASIS&T, USA), ● Best Paper Award, 2017, ASIS&T(USA) SIG III ● Emerald Award of Excellence for Outstanding Paper, 2009 ● A-LIEP Best Paper Award in 2006 ● FULBRIGHT AWARDS ○ Pre-Doc (2000-2001) University of Texas at Austin, USA ○ Post-Doc (2009-2010) University of Missouri, Columbia, USA ○ Fulbright Occasional Lecture Fund, 2010, North Carolina, USA ● Asian Library Leaders “Award for Professional Excellence – 2013, SRFLIS, Delhi, India. -

Dr Hussain Mohi Ud Din Qadri

MASTERING THE DATA REVOLUTION - IN THE SHADOW OF COVID-19 THE ART OF MAKING SMART SHARI’A DECISIONS IN ISLAMIC BANKING AMIDST COVID-19 AN EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW with DR HUSSAIN MOHIUDDIN QADRI PRESIDENT, MINHAJ UL QURAN INTERNATIONAL & DEPUTY CHAIRMAN, BOARD OF GOVERNORS MINHAJ UNIVERSITY LAHORE ISFIRE ISFIRE COVER STORY COVER STORY Dr Hussain Mohi-ud-Din Qadri, let us led to my interest in Islamic banking the fleet of financial products offered start with yourself by asking how you and finance, inspired and motivated by Islamic financial institutions THE ISLAMIC ECONOMIC got interested in Islamic finance on a me to study further, contemplate throughout the world? SYSTEM, THOUGH NOT personal level. and become a representative of the Product development is one of As you know that Minhaj-ul-Quran Islamic economic system. After joining the paramount requisites for the CURRENTLY ON THE International has been founded by the Minhaj University, the first two sustainability of the Islamic banking Shaykh-ul-Islam Prof. Dr. Muhammad new departments I established was and finance industry at a global level. SCENE WITH ITS ENTIRE Tahir-ul-Qadri in 1980 and he based the School of Islamic Economics, Without bringing innovative and it on knowledge and education. The Banking and Finance, and the customer-tailored products, Islamic BEAUTY AND EXCELLENCE, objectives behind this step were to International Center for Research banking and finance industry would revive the values, factors, elements and in Islamic Economics (ICRIE). These become less attractive for the existing CONTAINS THE programmes that had been granted platforms have been used to organise customers and not be able to attain to the Ummah by the Holy Prophet Pakistan’s biggest conference of Islamic new ones. -

Baccalaureate Degree Program Catalog 20-21 1 Contents Message from the Rector

BACCALAUREATE DEGREE PROGRAM CATALOG 20-21 1 CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE RECTOR Message from the Rector 3 Preface 4 Introduction to FCCU 5 Campus 11 Student Life 13 Fee Structure 18 Financial Aid and Merit Scholarships 21 Academic Policies and Procedures 23 Academic Support for Students 42 Awards 44 Medals 46 Liberal Arts 50 Careers and Internships 52 The International Education Office 54 Department of Chemistry 56 Department of Computer Science 65 Department of Economics 77 Forman Christian College is a chartered university that offers an American-style 4-year Baccalaureate Department of Education 86 (Hons) degree program designed to meet world-class standards. As a private not-for-profit University, our Department of English 91 focus is on providing the best possible education for our students. For over 150 years, FCCU has been Department of Environmental Sciences 105 providing quality education to young men and women of the region. We have produced graduates who Department of Geography 114 have leadership positions in government, business, education, various professions, religion and arts. Department of Health and Physical Education 122 Department of History 125 Our high-quality faculty takes personal interest in each student and each student has a member of the Department of Mass Communication 131 faculty to serve as his or her academic advisor. Teaching standards are ensured with an up-to-date Department of Mathematics 138 curriculum and by bringing in the latest developments in each field. Department of Pharmacy 146 Department of Philosophy 156 Located on a beautiful and safe campus with many academic buildings, sports grounds and a swimming Department of Physics 161 pool, we have a rich tradition of providing co-curricular activities through various student societies and Department of Political Science 168 sports. -

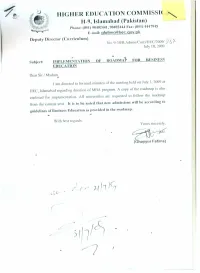

Letter-Implementation of Roadmap-Business

HIGHER EDUCA TlON COMMISSl( ]-[-9, Islamabad (Pakistan) Phone: (051) 90402441, 90402444 Fax: (051) 444794~ E-mail: [email protected] Deputy Director (Curriculum) No. 9-30/B./\dmin/Curri/I-IEC/2009/ j) ~ J-- July 18,2009 ~ Subject: IMPLEMENTATION OF ROADMAP FOR n.tJSINESS EDUCATION Dear Sir / Madam, - r am directed to forward minutes or the meeting held on July 3, 2009 at BEC, Islamabad regarding duration of MBA program. A copy of the roadrnap is also enclosed for implementation. All universities are requested to follow the roadrnap from the current year. It is to he noted that new admissions will he according to guidelines of Business Education as provided in the roadmap. With best regards. ..~>-:i~ (Ghayyur Fatima) J·t !llC;r " (' t..,.- ." ... ) I 1. The Registrar, Riphah International University, Islamic International Medical Complex, }th A venue, G-7/4, Islamabad. 2. The Registrar, .l.. Foundation University, 170 B, Street No. 68, F-IO/3, Islamabad. 3 The Registrar, Al-Khair University, Mirpur, AJK. -.:.. -- 4. The Registrar, Mohi-ud-Din Islamic University, Nerian Shari f, Trar Khal, 1> Azad Kash m ir. ., 5. The Registrar, Iqra University, . 8-B/2, Zarghoon Road, Quetta. 6. The Registrar, CECOS University ofInforrnajion Technology & Emerging Sciences, Phase- vi, H ayatabad, P.O. BoxA94,Saddar Road, ~ Peshawar. 7. ..; The Registrar, City University of Science & TnformatiC!.p Technology, GT Road, Nishrarabad, ' Peshawar City. ..i 8. The Registrar, Northern University, 3 The Mall, Nowshera Cantt. 9. The Registrar, Preston University, Old Government Degree College No.2, ..•... K.D.A., Phase-If, Kohat. 10. The Registrar, Qurtuba University of Science & Information Technology, D.T. -

Kamran Bashir [email protected]

Kamran Bashir [email protected] EDUCATION 2012-2018 PhD, Department of History University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Dissertation Andrew Rippin (2012-2016) Supervisors Derryl Maclean & Neilesh Bose (2016-18) 2014-2016 Graduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education Dept. of Educational Psychology / Learning & Teaching Centre University of Victoria Fall 2013 Doctoral Coursework in South Asian Islam Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada 2010-2012 MA in Muslim Cultures, London, United Kingdom Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations Affiliated with The Aga Khan University, Pakistan 2009-2010 Diploma in Arabic Language and Literature Department of Languages, Oriental College University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan 1992-1994 MBA, Institute of Business Administration Punjab University, Lahore, Pakistan ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2019- Assistant Professor Department of Liberal Arts Beaconhouse National University Lahore, Pakistan 2017-2018 Sessional Instructor Department of Humanities Camosun College Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Kamran Bashir 2017-2018 Instructor Division of Continuing Studies (Humanities) University of Victoria Victoria, British Columbia, Canada 2016-2017 Sessional Instructor Department of History University of Victoria Victoria, British Columbia, Canada TEACHING INTERESTS Formative Period of Islam Modern South Asia and Islam Historiography / Philosophy of History Survey of Islamic History History of South Asia Qur’anic Studies Cultural Anthropology World Religions INSTITUTIONAL AFFILIATIONS/ RESEARCH COLLABORATIONS Summer 2018 Collaborated with Sheila Yeoman on a book project, involving archival research, that is aimed at writing a biography of Annie Gale (1876-1970), the first woman alderman in the British Empire. 2017-2018 Research Associate Centre for Global Studies, University of Victoria 2015-16 Research Assistant to Dr.