Lirjell Lirjell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{FREE} the Confidential Agent: an Entertainment

THE CONFIDENTIAL AGENT: AN ENTERTAINMENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Graham Greene | 272 pages | 22 Jan 2002 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099286196 | English | London, United Kingdom The Confidential Agent: An Entertainment PDF Book Graham Greene. View all 3 comments. I am going to follow this up with The Heart of the Matter. Neil Forbes Holmes Herbert This edition published in by Viking Press in New York. This wistful romance is one of Greene's other masterstrokes of plotting; he is refreshingly unabashed about any pig-headed question of decency and he lets this romance flow in seamlessly and incidentally into the narrative to lend it a real heart of throbbing passion. Shipping to: Worldwide. Buy this book Better World Books. Seller information worldofbooksusa Not in Library. Clear your history. The confidential agent: an entertainment , The Viking Press. In a small continental country civil war is raging. It has a fast-moving plot, reversals of fortune, and plenty of action. It is not exactly foiling a diabolical conspiracy perpetuated by a grand, preening super-villain or sneaking behind enemy lines. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? The Power And The Glory was a deliberate exercise in exploring religion and morality, and Greene did not expect it to sell very well. Edit Did You Know? Well, it is. So, despite a promising start and interesting plot, the story itself loses grip on a number of occasions because there is little chemistry, or tension, between the characters - not between D. So he writes this book in the mornings, then writes the "serious" novel in the afternoons; whilst helping dig trenches on London's commons with the war looming. -

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Nesetrilovai Reflection1930s O

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Reflection of the 1930´s British Society in Graham Greene´s Brighton Rock Iva Nešetřilová Bachelor thesis 2017 Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využila, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byla jsem seznámena s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1 autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Souhlasím s prezenčním zpřístupněním své práce v Univerzitní knihovně. V Pardubicích dne 17.3.2017 Iva Nešetřilová Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Olga Roebuck, M.Litt. Ph.D. for giving me the opportunity to choose this topic, for her professional help, advice, and, especially, for the time she had spent when consulting my work. Annotation This paper examines and analyses the reflection of British Society in the novel Brighton Rock by Graham Green. The first part explores the situation in Britain around the 1930s, the period when the book was written and published, and briefly focuses on the changing landscape brought about by the Depression and aftermath of the First World War. The emphasis is confined mostly to how these changes affected the lower classes, and a brief description of what constitutes working class is provided. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Introduction

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Graham Greene (ed.), The Old School (London: Jonathan Cape, 1934) 7-8. (Hereafter OS.) 2. Ibid., 105, 17. 3. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life (London: Bodley Head, 1971) 72. (Hereafter SL.) 4. OS, 256. 5. George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (London: Gollancz, 1937) 171. 6. OS, 8. 7. Barbara Greene, Too Late to Turn Back (London: Settle and Bendall, 1981) ix. 8. Graham Greene, Collected Essays (London: Bodley Head, 1969) 14. (Hereafter CE.) 9. Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads (London: Longmans, Green, 1939) 10. (Hereafter LR.) 10. Marie-Franc;oise Allain, The Other Man (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 25. (Hereafter OM). 11. SL, 46. 12. Ibid., 19, 18. 13. Michael Tracey, A Variety of Lives (London: Bodley Head, 1983) 4-7. 14. Peter Quennell, The Marble Foot (London: Collins, 1976) 15. 15. Claud Cockburn, Claud Cockburn Sums Up (London: Quartet, 1981) 19-21. 16. Ibid. 17. LR, 12. 18. Graham Greene, Ways of Escape (Toronto: Lester and Orpen Dennys, 1980) 62. (Hereafter WE.) 19. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: Heinemann, 1962) 11. (Hereafter JWM). 20. Christopher Isherwood, Foreword, in Edward Upward, The Railway Accident and Other Stories (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972) 34. 21. Virginia Woolf, 'The Leaning Tower', in The Moment and Other Essays (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974) 128-54. 22. JWM, 4-10. 23. Cockburn, 21. 24. Ibid. 25. WE, 32. 26. Graham Greene, 'Analysis of a Journey', Spectator (September 27, 1935) 460. 27. Samuel Hynes, The Auden Generation (New York: Viking, 1977) 228. 28. ]WM, 87, 92. 29. Ibid., 272, 288, 278. -

Graham Greene and the Idea of Childhood

GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD APPROVED: Major Professor /?. /V?. Minor Professor g.>. Director of the Department of English D ean of the Graduate School GRAHAM GREENE AND THE IDEA OF CHILDHOOD THESIS Presented, to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Martha Frances Bell, B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. FROM ROMANCE TO REALISM 12 III. FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE 32 IV. FROM BOREDOM TO TERROR 47 V, FROM MELODRAMA TO TRAGEDY 54 VI. FROM SENTIMENT TO SUICIDE 73 VII. FROM SYMPATHY TO SAINTHOOD 97 VIII. CONCLUSION: FROM ORIGINAL SIN TO SALVATION 115 BIBLIOGRAPHY 121 ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A .narked preoccupation with childhood is evident throughout the works of Graham Greene; it receives most obvious expression its his con- cern with the idea that the course of a man's life is determined during his early years, but many of his other obsessive themes, such as betray- al, pursuit, and failure, may be seen to have their roots in general types of experience 'which Green® evidently believes to be common to all children, Disappointments, in the form of "something hoped for not happening, something promised not fulfilled, something exciting turning • dull," * ar>d the forced recognition of the enormous gap between the ideal and the actual mark the transition from childhood to maturity for Greene, who has attempted to indicate in his fiction that great harm may be done by aclults who refuse to acknowledge that gap. -

Wireless Women: the “Mass” Retreat of Brighton Rock Jeffrey Sconce Northwestern University

47 Wireless Women: The “Mass” Retreat of Brighton Rock Jeffrey Sconce Northwestern University All popular fi ction must feature a romantic couple, and so it is in the open- ing pages of Brighton Rock (1938) that Graham Greene introduces Pinkie and Rose, the teenagers whose abrasive courtship and perverse marriage will both enact and travesty this convention as the novel unfolds. When Pinkie fi rst meets Rose, she is working at Snow’s as a waitress. Entering the establishment, Pinkie encounters a wireless set “droning a programme of weary music broadcast by a cinema organist—a great vox humana trembl[ing] across the crumby stained desert of used cloths: the world’s wet mouth lamenting over life” (24). This reference to the weary lamentations of wireless remains an isolated detail until moments before Pinkie takes his fatal plunge over the cliff in the novel’s closing pages. Having taken Rose up the coast from Brighton with plans to facilitate her suicide, the couple sits for a few awkward moments in an empty hotel lounge. As Rose works on her half of the couple’s double-suicide note, to be left behind for the benefi t of “Daily Express readers, to what one called the world” (260), wireless makes a brief but meaningful re-appearance as that world speaks back. “The wireless was hidden behind a potted plant; a violin came wailing out, the notes shaken by atmospherics,” writes Greene (250). Later, the violin fades away and “a time signal pinged through the rain. A voice behind the plant gave them the weather report—storms coming up from the Continent, a depression in the Atlantic, tomorrow’s forecast” (251). -

The Modern World Through the Luminous Path of Prose Fiction: Reading Graham Greene’S a Burnt-Out Case and the Confidential Agent As Dystopian Novels

Nebula 6.2 , June 2009 The Modern World through the Luminous Path of Prose Fiction: Reading Graham Greene’s A Burnt-out Case and The Confidential Agent as Dystopian Novels. By Ayobami Kehinde What an absurd thing it was to expect happiness in a world so full of misery…. Point me out the happy man and I will point you out either egotisms, evil - or else an absolute ignorance (Graham Greene, The Heart of the Matter, 1948: 117) Graham Greene was undoubtedly one of the most gifted and acclaimed novelists of the War/Post-war era in Britain. His novels reflect a constant search for new novelistic modes of expression capable of visualizing the disillusionment and malaise of the modern world. According to Waldo Clarke (1976), an enduring trait of Greene’s fiction is the willingness to look at the repulsive face of the twentieth century. Since literature mostly reflects the mood of its age and enabling contexts, Greene’s fiction dwells on the conflicts and pains of the modern world. The central burden of this discourse is to prove that Greene’s novels steadily progressed in his bold use of the convention of dystopian fiction. It has been proved elsewhere that Greene’s The Power and the Glory and The Heart of the Matter are quintessential existential dystopian novels (See: Ayo Kehinde, 2004). However, in this present paper, an attempt is made to study more closely the dystopian features and political and ideological implications of the deployment of this convention in Greene’s The Confidential Agent and A Burnt-out Case . -

"Freedom and Alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and Other Related Texts."

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses "Freedom and alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and other related texts." Breeze, Brian How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Breeze, Brian (2005) "Freedom and alienation in Graham Greene's "Brighton Rock," Albert Camus' "The Plague," and other related texts.". thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42557 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ FREEDOM AND ALIENATION in Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, Albert Camus’ The Plague, and other related texts. BRIAN BREEZE M.Phil. 2005 UNIVERSITY OF WALES SWANSEA PRIFYSGOL CYMRU ABERTAWE ProQuest N um ber: 10805306 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Graham Greene's Work in the Time of the Cold

Jihočeská univerzita v Českých Budějovicích Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglistiky Bakalářská práce Graham Greene’s Work in the Time of the Cold War Vypracoval: František Linduška Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Alice Sukdolová, Ph.D. České Budějovice 2017 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že svoji bakalářskou práci jsem vypracoval samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě – v úpravě vzniklé vypuštěním vyznačených částí archivovaných pedagogickou fakultou elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. 11.7.2017 Podpis Poděkování Tímto bych chtěl poděkovat vedoucí této bakalářské práce PhDr. Alici Sukdolové, Ph.D. za odborné vedení, za pomoc a rady při zpracování všech údajů a v neposlední řadě i za trpělivost a ochotu, kterou mi v průběhu psaní této práce věnovala. Abstrakt Tato práce zkoumá vliv politického prostředí na tvorbu anglického prozaika Grahama Greena ve druhé polovině jeho tvůrčího života. Zaměří se na proměnu stylu psaní autora, psychologický a morální vývoj charakterů hlavních hrdinů a na celkovou charakteristiku Greenovy poetiky. -

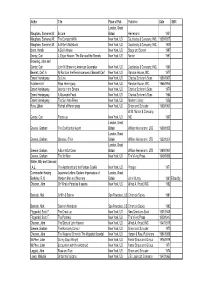

Eng Book2002

Author Title Place of Pub. Publisher Date ISBN London, Great Maugham, Somerset W. Encore Britain Heinemann 1951 Maugham, Somerset W. The Constant Wife New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1926/1927 Maugham, Somerset W. A Writer's Notebook New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1949 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House New York, US Stage and Screen 1997 Gentry, Curt J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets New York, US Norton 1991 Browning, John and Gentry, Curt John M. Browning American Gunmaker New York, US Doubleday & Company, INC. 1964 Bennett, Cerf. A At Random the Reminiscences of Bennett Cerf New York, US Random House, INC. 1977 Ernest Hemingway By Line New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1956/1967 Hotchner A.E. Papa Hemingway New York, US Random House, INC. 1955/1966 Ernest Hemingway Islands in the Stream New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1970 Ernest Hemingway A Moveable Feast New York, US Charles Scribner's Sons 1964 Ernest Hemingway The Sun Also Rises New York, US Modern Library 1926 Ross, Lillian Portrait of Hemingway New York, US Simon and Schuster 1950/1961 W.W. Norton & Company, Gentry, Curt Frame-up New York, US INC 1967 London, Great Greene, Graham The Confidential Agent Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1939/1952 London, Great Greene, Graham Stamboul Train Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1932/1951 London, Great Greene, Graham A Burnt-Out Case Britain William Heinemann. LTD 1960/1961 Greene, Graham The 3rd Man New York, US The Viking Press 1949/1950 Wilder, Billy and Diamond, I.A.L. The Apartment and the Fortune Cookie New York, US Praeger 1971 Commander Hasting Japanese Letters: Eastern Impressions of London, Great Berkeley, R.N. -

The Ambivalent Catholic Modernity of Graham Greene’S

THE AMBIVALENT CATHOLIC MODERNITY OF GRAHAM GREENE’S BRIGHTON ROCK AND THE POWER AND THE GLORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In English By Karl O’Hanlon, B.A. Washington D.C. 28 th April, 2010 THE AMBIVALENT CATHOLIC MODERNITY OF GRAHAM GREENE’S BRIGHTON ROCK AND THE POWER AND THE GLORY Karl O’Hanlon, B.A. Thesis Advisor: John Pfordresher, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis argues that the “religious sense” which emerged from Graham Greene’s Catholicism provides the basis for the critique of the ethics of modernity in his novels Brighton Rock (1938) and The Power and the Glory (1940). In his depiction of the self-righteous Ida Arnold in Brighton Rock , Greene elicits some problems inherent in modern ethical theory, comparing secular “right and wrong” unfavourably with a religious sense of “good and evil.” I suggest that the antimodern aspects of Pinkie in Brighton Rock are ultimately renounced by Greene as potentially dangerous, and in The Power and the Glory his critique of modernity evolves to a more ambivalent dialectic, in which facets of modernity are affirmed as well as rejected. I argue that this evolution in stance constitutes Greene’s search for a new philosophical and literary idiom – a “Catholic modernity.” ii With sincere thanks to John Pfordresher, for the great conversations about Greene, encouragement, careful reading, and patience in waiting for new chapter drafts, without which this thesis would have been much the poorer.