The Holocaust and the Maternal Body: an Exploration of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[MFH] Libro Free Stalingrad: Victory on the Volga](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9437/mfh-libro-free-stalingrad-victory-on-the-volga-59437.webp)

[MFH] Libro Free Stalingrad: Victory on the Volga

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : Stalingrad: Victory On The Volga (Images Of War) PDF STALINGRAD: VICTORY ON THE VOLGA (IMAGES OF WAR) Tapa blanda Ilustrado, 20 agosto 2009 Author : Nik Cornish Descripcin del productoCrticasA starkly moving pictorial record of the deadly battle that was the turning point of the Second World War. Nic Cornish s selection of images portrays Stalingrad as you have never seen it before and will never be able to forget. --Chris BucklandBiografa del autorNik Cornish is a former head teacher whose passionate interest in the world wars on the Eastern Front and in Russias military history in particular has led to a series of important books on the subject including Images of Kursk, Stalingrad: Victory on the Volga, Berlin: Victory in Europe, Partisan Warfare on the Eastern Front 1941-1944, The Russian Revolution: World War to Civil War 1917-1921, Hitler versus Stalin: The Eastern Front 1941-1942 Barbarossa to Moscow, Hitler versus Stalin: The Eastern Front 1942-1943 Stalingrad to Kharkov and Hitler versus Stalin: The Eastern Front 1943-1944 Kursk to Bagration. stalingrad This excellent book describes in detail,both in pictures and text, the most deadly battle of World War 2(August 42-February 43)which caused casualties in the region of 2 m1llion and hinged on Stalingrad.Through 9 chapters the author outlines the path of battle that ended in stalemate which was eventuslly broken by the Soviet army with the assistanco of winter and the failure of the German supply lines.The pictures are good for the time and place and well illustrate the horrors of war. -

Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War

International Feminist Journal of Politics ISSN: 1461-6742 (Print) 1468-4470 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfjp20 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War Joanna Tidy To cite this article: Joanna Tidy (2015) Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 17:3, 454-472, DOI: 10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616742.2014.967128 Published online: 02 Dec 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 248 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfjp20 Download by: [University of Massachusetts] Date: 28 June 2016, At: 13:24 Gender, Dissenting Subjectivity and the Contemporary Military Peace Movement in Body of War JOANNA TIDY School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS), University of Bristol, UK Abstract ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This article considers the gendered dynamics of the contemporary military peace move- ment in the United States, interrogating the way in which masculine privilege produces hierarchies within experiences, truth claims and dissenting subjecthoods. The analysis focuses on a text of the movement, the 2007 documentary -

Surv Surv Script

Surviving Survival 9/2/09 p.1 SURVIVING SURVIVAL ** Bach Morimur I’ve been thinking about survivors: survivors of holocaust, of genocide, survivors of terrorist attacks. and survivors of illness, of epidemic . survivors of domestic violence, of poverty, of deprivation. My question is not – how do you survive? My question is – how do you survive your own survival? Because it’s a blessing to live through something, to escape the body’s or the spirit’s destruction. But what about those you left behind – the ones who didn’t make it? the other patient, the war buddy, the little sister; the fireman, the rescue worker… the ones who did not survive? You don’t forget them. You can’t. I’M EK. THIS TIME ON S&S – SURVIVING SURVIVAL. What is the way to healing? Some survivors say you must forget the past, bury the loss, put it behind you as quickly as possible. Others need to mourn, to memorialize; they tell their stories over and over to anyone who will listen. It is important to have a purpose, a goal, a reason that’s it’s all right for you to have been the one who was saved. You dedicate your life to something: to raising children, to bearing witness, to making music, to saving others. CAMBODIA Start with mood music – melancholy – for Cambodia: *** NEW INTERNATIONAL TRIO (something sad-sounding) OR *** Rak Smey Khemera: "Light From Heaven" TK. 5? 6? It’s almost impossible to comprehend what happened in Cambodia during Pol Pot’s regime, beginning in 1975: an entire population uprooted, deliberately murdered by the HUDNREDS of thousands in the killing fields . -

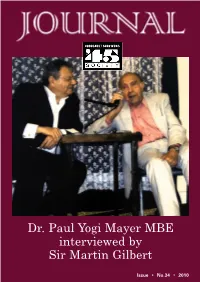

Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE Interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert

JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 1 Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert Issue • No.34 • 2010 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 2 CH ARTER ED AC C OU NTANTS MARTIN HELLER 5 North End Road • London NW11 7RJ Tel 020 8455 6789 • Fax 020 8455 2277 email: [email protected] REGISTERED AUDIT ORS simmons stein & co. SOLI CI TORS Compass House, Pynnacles Close, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 4AF Telephone 020 8954 8080 Facsimile 020 8954 8900 dx 48904 stanmore web site www.simmons-stein.co.uk Gary Simmons and Jeffrey Stein wish the ’45 Aid every success 2 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 3 THE ’45 AID SOCIETY (HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS) PRESIDENT SECRETARY SIR MARTIN GILBERT C.B.E.,D.LITT., F.R.S.L M ZWIREK 55 HATLEY AVENUE, BARKINGSIDE, VICE PRESIDENTS IFORD IG6 1EG BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. (SOUTHAMPTON) COMMITTEE MEMBERS LORD GREVILLE JANNER OF M BANDEL (WELFARE OFFICER), BRAUNSTONE Q.C. S FREIMAN, M FRIEDMAN, PAUL YOGI MAYER M.B.E. V GREENBERG, S IRVING, ALAN MONTEFIORE, FELLOW OF BALLIOL J KAGAN, B OBUCHOWSKI, COLLEGE, OXFORD H OLMER, I RUDZINSKI, H SPIRO, DAME SIMONE PRENDEGAST D.B.E., J.P., D.L. J GOLDBERGER, D PETERSON, KRULIK WILDER HARRY SPIRO SECRETARY (LONDON) MRS RUBY FRIEDMAN CHAIRMAN BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. SECRETARY (MANCHESTER) (SOUTHAMPTON) MRS H ELLIOT VICE CHAIRMAN ZIGI SHIPPER JOURNAL OF THE TREASURER K WILDER ‘45 AID SOCIETY FLAT 10 WATLING MANSIONS, EDITOR WATLING STREET, RADLETT, BEN HELFGOTT HERTS WD7 7NA All submissions for publication in the next issue (including letters to the Editor and Members’ News Items) should be sent to: RUBY FRIEDMAN, 4 BROADLANDS, HILLSIDE ROAD, RADLETT, HERTS WD7 7BX ACK NOW LE DG MEN TS SALEK BENEDICT for the cover design. -

Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film

Enwheeled: Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film Penny Lynne Wolfson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design MA Program in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution and Parsons The New School for Design 2014 2 Fall 08 © 2014 Penny Lynne Wolfson All Rights Reserved 3 ENWHEELED: TWO CENTURIES OF WHEELCHAIR DESIGN, FROM FURNITURE TO FILM TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i PREFACE ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1. Wheelchair and User in the Nineteenth Century 31 CHAPTER 2. Twentieth-Century Wheelchair History 48 CHAPTER 3. The Wheelchair in Early Film 69 CHAPTER 4. The Wheelchair in Mid-Century Films 84 CHAPTER 5. The Later Movies: Wheelchair as Self 102 CONCLUSION 130 BIBLIOGRAPHY 135 FILMOGRAPHY 142 APPENDIX 144 ILLUSTRATIONS 150 4 List of Illustrations 1. Rocking armchair adapted to a wheelchair. 1810-1830. Watervliet, NY 2. Pages from the New Haven Folding Chair Co. catalog, 1879 3. “Dimension/Weight Table, “Premier” Everest and Jennings catalog, April 1972 4. Screen shot, Lucky Star (1929), Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell 5. Man in a Wheelchair, Leon Kossoff, 1959-62. Oil paint on wood 6. Wheelchairs in history: Sarcophagus, 6th century A.D., China; King Philip of Spain’s gout chair, 1595; Stephen Farffler’s hand-operated wheelchair, ca. 1655; and a Bath chair, England, 18th or 19th century 7. Wheeled invalid chair, 1825-40 8. Patent drawing for invalid locomotive chair, T.S. Minniss, 1853 9. -

Il Ruolo E La Funzione Del Falso Nella Storia Della Shoah

IL RUOLO E LA FUNZIONE DEL FALSO NELLA STORIA DELLA SHOAH. STORICI, AFFAIRES E OPINIONE PUBBLICA Thèse en cotutelle entre l’Université de Bologne Alma Mater Studiorum et l’Université Paris X Nanterre (Ed 395 École Doctorale Milieux, Cultures et Sociétés du Passé et du Présent, Doc Histoire du monde contemporain). Membres du jury: Prof. Henry Rousso (rapporteur), Prof. Luciano Casali (rapporteur), Prof. Marie Anne Matard Bonucci (rapporteur), Prof. Alfonso Botti (Président du jury). «Citai di nuovo, per non diventare idillico in prima persona, il poeta che dice: “Quanto hai vissuto, nessuna potenza del mondo può togliertelo”. Ciò che abbiamo realizzato nella pienezza della nostra vita passata, nella sua ricchezza d’esperienza, questa ricchezza interiore, nessuno può sottrarcela. Ma non solo ciò che abbiamo vissuto, anche ciò che abbiamo fatto, ciò che di grande abbiamo pensato e ciò che abbiamo sofferto... Tutto ciò l’abbiamo salvato rendendolo reale, una volta per sempre. E se pure si tratta di un passato, è assicurato per l’eternità! Perché essere passato è ancora un modo di essere, forse, anzi, il più sicuro». Viktor E. Frankl - Uno psicologo nei Lager INDICE INTRODUZIONE p. 4 PREMESSA p. 15 CAPITOLO I QUESTIONI DI METODO STORICO p. 32 1. La dimensione di massa della storia contemporanea. p. 33 2. La storia del tempo presente. p. 37 3. Della difficile coesistenza di storia e memoria. p. 42 4. Il dovere di storia. p. 46 5. Sulla testimonianza. p. 51 6. Le testimonianze della Shoah. p. 56 CAPITOLO II FALSI TESTIMONI, ALCUNI CASI DI STUDIO p. 67 1. I primi falsari. -

Thesis Title the Lagermuseum Creative Manuscript and 'Encountering Auschwitz: Touring the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum' C

Thesis Title The Lagermuseum Creative Manuscript and ‘Encountering Auschwitz: Touring the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum’ Critical Thesis Author Dr Claire Griffiths, BA (Hons), MA, PhD Qualification Creative and Critical Writing PhD Institution University of East Anglia, Norwich School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing Date January 2015 Word Count 91,102 (excluding appendices) This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract The Lagermuseum My creative manuscript – an extract of a longer novel – seeks to illuminate a little- known aspect of the history of the Auschwitz concentration and death camp complex, namely the trade and display of prisoner artworks. However, it is also concerned with exposing the governing paradigms inherent to contemporary encounters with the Holocaust, calling attention to the curatorial processes present in all interrogations of this most contentious historical subject. Questions relating to ownership, display and representational hierarchies permeate the text, characterised by a shape-shifting curator figure and artworks which refuse to adhere to the canon he creates for them. The Lagermuseum is thus in constant dialogue with my critical thesis, examining the fictional devices which often remain unacknowledged within established -

Lessons from the Treblinka Archive: Transnational Collections and Their Implications for Historical Research Chad S.A

Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies Volume 5 Article 14 2018 Lessons from the Treblinka Archive: Transnational Collections and their Implications for Historical Research Chad S.A. Gibbs University of Wisconsin-Madison, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas Part of the Archival Science Commons, European History Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, Chad S.A. (2018) "Lessons from the Treblinka Archive: Transnational Collections and their Implications for Historical Research," Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies: Vol. 5 , Article 14. Available at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/jcas/vol5/iss1/14 This Case Study is brought to you for free and open access by EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies by an authorized editor of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lessons from the Treblinka Archive: Transnational Collections and their Implications for Historical Research Cover Page Footnote No one works alone. True to this statement, I owe thanks to many for their assistance in the completion of this work. This article began as a seminar paper in Professor Kathryn Ciancia's course "Transnational Histories of Modern Europe." I thank her and my classmates for many enlightening discussions and the opportunity to challenge my ongoing research in new ways. As always, I thank my advisor at the University of Wisconsin- Madison, Professor Amos Bitzan. His guidance and example are always greatly appreciated. In completing this work, I also had the support of my colleague Brian North and Professors Christopher Simer of the University of Wisconsin-River Falls and Connie Harris of Dickinson State University. -

Russians Abroad-Gotovo.Indd

Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) The Real Twentieth Century Series Editor – Thomas Seifrid (University of Southern California) Russians abRoad Literary and Cultural Politics of diaspora (1919-1939) GReta n. sLobin edited by Katerina Clark, nancy Condee, dan slobin, and Mark slobin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: The bibliographic data for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-214-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61811-215-6 (electronic) Cover illustration by A. Remizov from "Teatr," Center for Russian Culture, Amherst College. Cover design by Ivan Grave. Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Table of Contents Foreword by Galin Tihanov ....................................... -

Bibliography on Medicine and the Holocaust

Bibliography on Medicine and the Holocaust Bibliography on Medicine and the Holocaust Medicine and the Holocaust - Articles 1. Abbott A. Max Planck Society admits to its predecessor's Nazi links. Nature. 2001 Jun 14;411(6839):726. PubMed. No Abstract. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.ezproxyhost.library.tmc.edu/pubmed/11460097 2. Bachrach S. Deadly medicine. Public Hist. 2007 Summer;29(3):19-32. PubMed. Abstract. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.ezproxyhost.library.tmc.edu/pubmed/18175449 3. Barilan YM. Medicine through the artist's eyes: before, during, and after the Holocaust. Perspect Biol Med. 2004 Winter;47(1):110-34. PubMed. Abstract. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.ezproxyhost.library.tmc.edu/pubmed 4. Barondess JA. Care of the medical ethos, with some comments on research: reflections after the holocaust. Perspect Biol Med. 2000 Spring;43(3):308-24. PubMed. No Abstract. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.ezproxyhost.library.tmc.edu/pubmed/10893721 5. Barondess JA. Medicine against society. Lessons from the Third Reich. JAMA. 1996 Nov 27;276(20):1657-61. PubMed. Abstract. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8922452 Comment in: • JAMA. 1996 Nov 27;276(20):1679-81. • JAMA. 1997 Mar 5;277(9):710. 6. Baten J, Wagner A. Autarchy, market disintegration, and health: the mortality and nutritional crisis in Nazi Germany, 1933-1937. Econ Hum Biol. 2003 Jan;1(1):1-28. PubMed. Abstract. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.ezproxyhost.library.tmc.edu/pubmed/15463961 7. -

Review of 2016 Programs

Olga Lengyel, 1908 - 2001 Review of 2016 Programs ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1 | Table of Contents I. About The Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights and The Memorial Library 2 II. The 2016 Summer Seminar on Holocaust Education 3 III. Mini-grant Program 6 IV. TOLI Satellite Seminar Program 14 V. Leadership Institute in New York City 26 VI. Professional Development/Conferences 27 VII. Seminar in Austria 28 VIII. Summer Seminar in Romania 34 IX. Summer Seminar in Bulgaria 38 X. Appendices 42 Appendix A: List of Participating Schools, Summer Seminar 2016 Appendix B: Calendar of Activities, Summer Seminar 2016 Appendix C: List of Participating Schools, Leadership Institute 2016 Appendix D: Calendar of Activities, Leadership Institute 2016 Faculty and Staff of the Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights: Sondra Perl, PhD, Program Director Jennifer Lemberg, PhD, Associate Program Director Wendy Warren, EdD, Satellite Seminar Coordinator Micha Franke, Dipl.Päd., Teaching Staff, New York and International Programs Oana Nestian Sandu, PhD, International Programs Coordinator Alice Braziller, MA, Teaching Staff, New York 2 | I. About the Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights (TOLI) and the Memorial Library The Olga Lengyel Institute for Holocaust Studies and Human Rights (TOLI) is a New York-based 501(c)(3) charitable organization providing professional development to inspire and sustain educators teaching about the Holocaust, genocide, and human rights in the United States and overseas. TOLI was created to further the mission of the Memorial Library, a private nonprofit established in 1962 by Holocaust survivor Olga Lengyel. In the fall of 1944, Olga was forced to board a cattle car bound for Auschwitz with her parents, her husband, and their two sons, yet she alone survived the war. -

University of Birmingham Department of Theology and Religion BA Philosophy, Religion and Ethics 09 24094 Dissertation

University of Birmingham Department of Theology and Religion BA Philosophy, Religion and Ethics 09 24094 Dissertation A Gendered Analysis of Prisoner-Physicians in KL Auschwitz, with a focus on Dr Gisella Perl SRN: 1424498 Word Count: 12,000 2 1424498 University of Birmingham School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion Dissertation cover sheet To be included with all assignments submitted for assessment Dissertation 09 24094 Dissertation (underline the dissertation you are 09 28285 LH 6000-word Dissertation submitting) Level H Student ID (SRN) 1424498 Actual 12,000 Word Count REMINDERS 1. By submitting this assignment you are declaring that it is not plagiarised, that it is all your own work, and that all quotations from, allusions to, and paraphrasing of the work of others have been appropriately cited and referenced. Refer to the School Handbook or speak to the School Plagiarism Officer if you have any questions concerning plagiarism. 2. It is your responsibility to ensure that you upload the correct version of your dissertation to the correct assignment section on Canvas. 3. A penalty of 5 marks will be imposed for each working day the assignment is late, until a grade of 0 is reached. 4. There is no leeway concerning word limits for the assignment. One mark will be deducted if your essay exceeds the word limit and a further mark for every 100 words that you are in excess e.g. 1 word over the limit will result in a 1 mark penalty, 101 words over is a 2 mark penalty etc. The word count includes all references, but excludes the title, bibliography, and this coversheet.