BY EDICHA, OJOCHIDE BLESSING PG/M.Sc./12/63197

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combating Corruption in Nigeria: a Critical Appraisal of the Laws, Institutions, and the Political Will Osita Nnamani Ogbu

Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 6 2008 Combating Corruption in Nigeria: A Critical Appraisal of the Laws, Institutions, and the Political Will Osita Nnamani Ogbu Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey Part of the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Ogbu, Osita Nnamani (2008) "Combating Corruption in Nigeria: A Critical Appraisal of the Laws, Institutions, and the Political Will," Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law: Vol. 14: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey/vol14/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Survey of International & Comparative Law by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ogbu: Combating Corruption in Nigeria COMBATING CORRUPTION IN NIGERIA: A CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF THE LAWS, INSTITUTIONS, AND THE POLITICAL WILL OSITA NNAMANI OGBU· I. INTRODUCTION Corruption is pervasive and widespread in Nigerian society. It has permeated all facets of life, and every segment of society is involved. In recent times, Nigeria has held the unenviable record of being considered one of the most corrupt countries among those surveyed I. The Political Bureau, set up under the Ibrahim Babangida regime, summed up the magnitude of corruption in Nigeria as follows: It [corruption] pervades all strata of the society. From the highest level of the political and business elites to the ordinary person in the village. Its multifarious manifestations include the inflation of government contracts in return for kickbacks; fraud and falsification of accounts in the public service; examination * Senior Lecturer, and Ag. -

NIGERIA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

NIGERIA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 6 January 2012 NIGERIA 6 JANUARY 2012 Contents Preface Latest news EVENTS IN NIGERIA FROM 16 DECEMBER 2011 TO 3 JANUARY 2012 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON NIGERIA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED AFTER 15 DECEMBER 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY (1960 – 2011) ........................................................................................... 3.01 Independence (1960) – 2010 ................................................................................ 3.02 Late 2010 to February 2011 ................................................................................. 3.04 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS (MARCH 2011 TO NOVEMBER 2011) ...................................... 4.01 Elections: April, 2011 ....................................................................................... 4.01 Inter-communal violence in the middle belt of Nigeria ................................. 4.08 Boko Haram ...................................................................................................... 4.14 Human rights in the Niger Delta ......................................................................... -

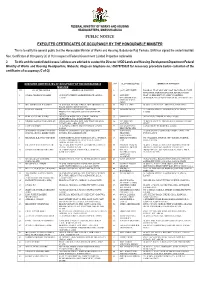

Executed Certificates of Occupancy by the Honourable Minister

FEDERAL MINISTRY OF WORKS AND HOUSING HEADQUARTERS, MABUSHI-ABUJA PUBLIC NOTICE EXECUTED CERTIFICATES OF OCCUPANCY BY THE HONOURABLE MINISTER This is to notify the general public that the Honourable Minister of Works and Housing, Babatunde Raji Fashola, SAN has signed the underlisted 960 Nos. Certificates of Occupancy (C of O) in respect of Federal Government Landed Properties nationwide. 2. To this end the underlisted lessees / allotees are advised to contact the Director / HOD Lands and Housing Development Department Federal Ministry of Works and Housing Headquarters, Mabushi, Abuja on telephone no.: 08078755620 for necessary procedure before collection of the certificates of occupancy (C of O). EXECUTED CERTIFICATES OF OCCUPANCY BY THE HONOURABLE S/N ALLOTTEE/LESSEE ADDRESS OF PROPERTY MINISTER S/N ALLOTTEE/LESSEE ADDRESS OF PROPERTY 31. (SGT) OTU IBETE ROAD 13, FLAT 2B, LOW COST HOUSING ESTATE, RUMUEME, PORT HARCOURT, RIVERS STATE 1 OPARA CHARLES NNAMDI 18 BONNY STREET, MARINEE BEACH, APAPA, 32. ANIYEYE FLAT 18, FED. DEPT OF AGRIC QUARTERS, LAGOS OVUOMOMEVBIE RUMMODUMAYA PORT HARCOURT, RIVERS STATE CHRISTY TAIYE (MRS) 2 MR. ADEBAYO S. FALODUN ALONG OGUNNAIKI STREET, OFF ADIGBOLUJA 33. ARO A.A. (MR.) BLOCK 55, PLOT 1302, ABESAN, LAGOS STATE ROAD, OJODU, OGUND STATE. 3 HUMAIRI AHMED HOUSE NO. 6, UYO STREET, GWARINPA 34. AHMADU MUSA 15, SAPARA STREET, MARINE BEACH, APAPA, PROTOTYPE HOUSING SCHEME GWARINPA, LAGOS ABUJA 4 FEMI AJAYI (MR. & MRS) NO 48, KOLA ORETUGA STREET, MEIRAN 35. UMAR ALI A. 9B BATHURST ROAD, APAPA, LAGOS ALIMOSHO L.G.A., LAGOS STATE 5 NWOGU EARNEST NWAOBILOR HOUSE 64B, ROAD 8, FED. LOW COST HOUSING 36. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 30Th November, 2010

6TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOURTH SESSION No. 45 621 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 30th November, 2010 1. The Senate met at 10:56 a.m. The Senate President read prayers. 2. Votesand Proceedings: The Senate President announced that he had examined the Votes and Proceedings of Thursday, 25th November, 2010 and approved same. By unanimous consent, the Votes and Proceedings were approved. 3. Messagefrom Mr. President: The Senate President announced that he had received a letter from the President, Commander-in- Chief of the Armed Forces of the Federation, which he read as follows: Appointment of a new Chairman for the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC): PRESIDENT, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA 25th November, 2010 Senator David Mark, GCON President of the Senate, Senate Chambers, National Assembly, Three Arms Zone, Abuja. Your Excellency, APPOINTMENT OF A NEW CHAIRMAN FOR THE INDEPENDENT CORRUPT PRACTICES AND OTHER RELATED OFFENCES COMMISSION PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 622 Tuesday, 30th November, 2010 No. 45 In line with the provision of Section 3 of the Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Act, Cap C.3l, LFN 2004, I forward the name of Bon. Justice Pius Olayiwola Aderemi, JSC, CON along with his curriculum vitae for kind consideration and confirmation by the Senate for appointment as Chairman of the Independent Corrupt Practices and other Related Offences Commission. Distinguished President of the Senate, it is my hope that, in the usual tradition of the Senate of the Federal Republic, this will receive expeditious consideration. Please accept, as usual, the assurances of my highest consideration. -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

Africa Report

PROJECT ON BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Africa April to June 2008 Volume: 1 Reports for the period April to May 2008 Principal Investigator: Prof. Dr. Ijaz Shafi Gilani Contributors Abbas S Lamptey Snr Research Associate Reports on Sub-Saharan AFrica Abdirisak Ismail Research Assistant Reports on East Africa INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Asia April to June 2008 Reports for the period April to May 2008 Volume: 1 Department of Politics and International Relations International Islamic University Islamabad 2 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Africa 2008 Table of contents Reports for the month of April Week-1 April 01, 2008 05 Week-2 April 08, 2008 63 Week-3 April 15, 2008 120 Week-4 April 22, 2008 185 Week-5 April 29, 2008 247 Reports for the month of May Week-1 May 06, 2008 305 Week-2 May 12, 2008 374 Week-3 May 20, 2008 442 Country profiles Sources 3 4 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD Weekly Presentation: April 1, 2008 Sub-Saharan Africa Abbas S Lamptey Period: From March 23 to March 29 2008 1. CHINA -AFRICA RELATIONS WEST AFRICA Sierra Leone: Chinese May Evade Govt Ban On Logging: Concord Times (Freetown):28 March 2008. Liberia: Chinese Women Donate U.S. $36,000 Materials: The NEWS (Monrovia):28 March 2008. Africa: China/Africa Trade May Hit $100bn in 2010:This Day (Lagos):28 March 2008. -

First Election Security Threat Assessment

SECURITY THREAT ASSESSMENT: TOWARDS 2015 ELECTIONS January – June 2013 edition With Support from the MacArthur Foundation Table of Contents I. Executive Summary II. Security Threat Assessment for North Central III. Security Threat Assessment for North East IV. Security Threat Assessment for North West V. Security Threat Assessment for South East VI. Security Threat Assessment for South South VII. Security Threat Assessment for South West Executive Summary Political Context The merger between the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), All Nigerian Peoples Party (ANPP) and other smaller parties, has provided an opportunity for opposition parties to align and challenge the dominance of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). This however will also provide the backdrop for a keenly contested election in 2015. The zoning arrangement for the presidency is also a key issue that will define the face of the 2015 elections and possible security consequences. Across the six geopolitical zones, other factors will define the elections. These include the persisting state of insecurity from the insurgency and activities of militants and vigilante groups, the high stakes of election as a result of the availability of derivation revenues, the ethnic heterogeneity that makes elite consensus more difficult to attain, as well as the difficult environmental terrain that makes policing of elections a herculean task. Preparations for the Elections The political temperature across the country is heating up in preparation for the 2015 elections. While some state governors are up for re-election, most others are serving out their second terms. The implication is that most of the states are open for grab by either of the major parties and will therefore make the electoral contest fiercer in 2015 both within the political parties and in the general election. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

A Critical Analysis of Grand Corruption with Reference to International Human Rights and International Criminal Law: the Case of Nigeria

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2017-4 A Critical Analysis of Grand Corruption with Reference to International Human Rights and International Criminal Law: The Case of Nigeria Florence Anaedozie Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Anaedozie, F. (2017) A Critical Analysis of Grand Corruption with Reference to International Human Rights and International Criminal Law: The Case of Nigeria. Doctoral thesis, 2017. doi:10.21427/D7V983 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License A Critical Analysis of Grand Corruption with Reference to International Human Rights and International Criminal Law: The Case of Nigeria By Florence Anaedozie, BA, LL.B, LL.M School of Languages, Law and Social Sciences College of Arts and Tourism Dublin Institute of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lead Supervisor: Dr Stephen Carruthers Advisory Supervisor: Dr Kevin Lalor April 2017 Abstract Grand corruption remains a domestic crime that is not directly addressed by the international human rights and international criminal law regulatory frameworks. Scholars argue that the right to a society free of corruption is an inherent human right because dignity, equality and participation significantly depend upon it. -

Ondo State Pocket Factfinder

INTRODUCTION Ondo is one of the six states that make up the South West geopolitical zone of Nigeria. It has interstate boundaries with Ekiti and Kogi states to the north, Edo State to the east, Delta State to the southeast, Osun State to the northwest and Ogun State to the southwest. The Gulf of Guinea lies to its south and its capital is Akure. ONDO: THE FACTS AND FIGURES Dubbed as the Sunshine State, Ondo, which was created on February 3, 1976, has a population of 3,441,024 persons (2006 census) distributed across 18 local councils within a land area of 14,788.723 Square Kilometres. Located in the South-West geo-political zone of Nigeria, Ondo State is bounded in the North by Ekiti/Kogi states; in the East by Edo State; in the West by Oyo and Ogun states, and in the South by the Atlantic Ocean. Ondo State is a multi-ethnic state with the majority being Yoruba while there are also the Ikale, Ilaje, Arogbo and Akpoi, who are of Ijaw extraction and inhabit the riverine areas of the state. The state plays host to 880 public primary schools, and 190 public secondary schools and a number of tertiary institutions including the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State Polytechnic, Owo, Federal College of Agriculture, Akure and Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo. Arguably, Ondo is one of the most resource-endowed states of Nigeria. It is agriculturally rich with agriculture contributing about 75 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The main revenue yielding crops are cocoa, palm produce and timber. -

The Jonathan Presidency, by Abati, the Guardian, Dec. 17

The Jonathan Presidency By Reuben Abati Published by The Jonathan Presidency The Jonathan Presidency By Reuben Abati A review of the Goodluck Jonathan Presidency in Nigeria should provide significant insight into both his story and the larger Nigerian narrative. We consider this to be a necessary exercise as the country prepares for the next general elections and the Jonathan Presidency faces the certain fate of becoming lame-duck earlier than anticipated. The general impression about President Jonathan among Nigerians is that he is as his name suggests, a product of sheer luck. They say this because here is a President whose story as a politician began in 1998, and who within the space of ten years appears to have made the fastest stride from zero to “stardom” in Nigerian political history. Jonathan himself has had cause to declare that he is from a relatively unknown village called Otuoke in Bayelsa state; he claims he did not have shoes to wear to school, one of those children who ate rice only at Xmas. When his father died in February 2008, it was probably the first time that Otuoke would play host to the kind of quality crowd that showed up in the community. The beauty of the Jonathan story is to be found in its inspirational value, namely that the Nigerian dream could still take on the shape of phenomenal and transformational social mobility in spite of all the inequities in the land. With Jonathan’s emergence as the occupier of the highest office in the land, many Nigerians who had ordinarily given up on the country and the future felt imbued with renewed energy and hope. -

An Assessment of Civil Military Relations in Nigeria As an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007

AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 BY MOHAMMED LAWAL TAFIDA DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA JUNE 2015 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled An Assessment of Civil-Military Relations in Nigeria as an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007 has been carried out and written by me under the supervision of Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi, Dr. Mohamed Faal and Professor Paul Pindar Izah in the Department of Political Science and International Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria. The information derived from the literature has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided in the work. No part of this dissertation has been previously presented for another degree programme in any university. Mohammed Lawal TAFIDA ____________________ _____________________ Signature Date CERTIFICATION PAGE This thesis entitled: AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science of the Ahmadu Bello University Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi ___________________ ________________ Chairman, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Dr. Mohamed Faal________ ___________________ _______________ Member, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Professor Paul Pindar Izah ___________________