Koyaanisqatsi in Cyberspace by Paul A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Mcdermott

LANDSCAPES AND THE MACHINE: ADDRESSING WICKED VALUATION PROBLEMS WHEN NORTH, SOUTH, EAST AND WEST MEET A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy by Michael McDermott Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building University of Technology, Sydney Supervisors: Associate Professor Jason Prior and Professor Spike Boydell 2015 Landscapes and the Machine: Addressing Wicked Valuation Problems when North, South, East and West Meet. i ABSTRACT This thesis is about engaging with the dynamic relationship between “landscapes”, “land tenure”, and the “machine”. The first term can be so broad as to mean every process and thing encountered, the second means the way that land is held by a person or group of persons, and the third means things both put together and used by humans to fulfil their wants and needs from the landscape. As a professional valuer I have been traditionally trained to engage at arms-length with the normative behaviour of persons or groups at the intersection of these three concepts, wherein those people and groups were willing but not compelled to engage. Such traditional valuation approaches are increasingly recognised as being insufficient to address wicked valuation problems of the diverse peoples and groups that inhabit the globe from North, South, East to West. This thesis develops a means of engaging with these wicked valuation problems in a suitably knowledgeable and prudent way. To do so the thesis adopts an exploratory approach guided by Whitehead’s process philosophy injunction of a creative advance into novelty. This approach is enacted through a range of data collection and analysis methods. -

Mr Trumble.Pdf

REVIEW OF EXHIBITIONS AND PUBLIC PROGRAMS AT THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AUSTRALIA SUBMISSION BY ANGUS TRUMBLE I wish to make the following submission in connection with DCITA’s 2003 Review of Exhibitions and Public Programs at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra. My thoughts about the NMA are largely the product of having for many years visited dozens museums all over the world, either out of interest or through my work as Curator of European Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide (1996 to 2001). However, I should also make it clear that I have had no professional contact with the NMA staff other than as an ordinary visitor, and it is in that capacity, not so much as an art museum curator, that I wish to comment on the building and aspects of the display, which I have studied carefully in the course of five visits in February and March this year. Despite the robust nature of many of my criticisms, I should say that I welcome the long-awaited arrival of the NMA. I believe it has a vital role to play in the cultural life of the nation, and the many problems that it must now solve are no more than temporary setbacks. None, apart from the terrible building, is insoluble, and even the building can be improved, I think, beyond measure. The architecture The design of the new NMA building is very poor and will not, I think, serve the long-term exhibition needs of the NMA. Nor will it open up new possibilities for public programming in the long term. -

Not Even Past NOT EVEN PAST

The past is never dead. It's not even past NOT EVEN PAST Search the site ... Of How a Hopi Ancient Word Became a Famous Experimental Film Like 65 Tweet by Montserrat Madariaga The theater is at its full capacity. The musicians are in place as the orchestra conductor starts to wave his arms in time with the image on the screen. There, little red dots emerge from a black background. They slowly widen and turn into capital letters: The word KOYAANISQATSI takes over. Keyboard notes evoking a church organ underline the mystery of the term and suit the dramatic hard-edged-typography. It is a Friday afternoon, February 23, 2018, in the Bass Concert Hall of the Texas Performing Art Center of The University of Texas, at Austin. The occasion is the screening of Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 lm, accompanied by the live performance of The Philip Glass Ensemble playing its original score music. Featured for the rst time to an ample public in the 1982 New York Film Festival, Koyaanisqatsi is an audiovisual art piece without dialogue or voiceover, deprived of any explicit narrative, that is nowadays a cult classic. It opens with a shot of the Holy Ghost Panel in Horseshoe Canyon, Utah, a human trace dated between 400 AD and 1100 AD. Then, footage of imposing natural landscapes and wildlife of the United States’ Southwest is followed by images of urban spaces: construction, crowded streets, demolitions, technology of the time, and so on. The collage escalates in its pace along with the music: utes, clarinet, trombone, viola, tuba, keyboards and vocals from time to time repeat the word “koyaanisqatsi” in a low pitched ceremonial tone that creates an apocalyptic atmosphere. -

GODFREY REGGIO (Director, Koyaanisqatsi) Is a Pioneer of a Film Form That Creates Poetic Images of Extraordinary Emotive Impact

GODFREY REGGIO (Director, Koyaanisqatsi) is a pioneer of a film form that creates poetic images of extraordinary emotive impact. Reggio is best known for the Qatsi Trilogy – essays of image and music, speechless narrations which question the world in which we live. Born in New Orleans in 1940, Reggio entered the Christian Brothers, a Roman Catholic Pontifical Order, at age 14 and remained as a monk until 1968. In 1963, he co-founded Young Citizens for Action, a community organization of juvenile street gangs. Reggio co-founded La Clinica de la Gente and La Gente, a community organizing project in Northern New Mexico’s barrios. In 1972, he co- founded the Institute for Regional Education in Santa Fe, a nonprofit organization focused on media, the arts, community organization and research. In collaboration with the New Mexico Chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, Reggio co- organized a multimedia public interest campaign on the invasion of privacy and the use of technology to control behavior. Reggio’s collaboration on Koyaanisqatsi with Ron Fricke (Director of Photography) and Philip Glass (Composer) gained an international audience, critical acclaim and launched the Qatsi Trilogy. Koyaanisqatsi has been played live over 200 times in venues worldwide. Reggio’s collaborations with Philip Glass, include: Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Powaqqatsi (1988), Naqoyqatsi (2002), Anima Mundi (1992), Evidence (1995) and Visitors (2013). In 1993, Reggio was invited by Luciano Benetton and Oliviero Toscani to develop a new school “to smell the future” – an enterprise of exploration and production in the arts, technology and mass media. Called Fabrica – Futuro Presente, it opened in the middle of the ‘90s in Treviso, Italy. -

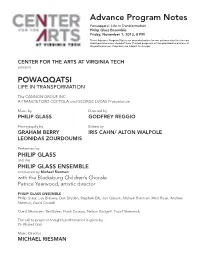

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

1. Information As Experience Good: Information Goods Are Experience Goods

Pricing Information Goods for Digital Libraries (Seminar aus Informationswirtschaft 4085) SS 2003 Strategies for the digital library of the WU - Focus on Rights Management Univ.-Ass. Mag. Dr. Michael Hahsler Univ. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Panny Abteilung für Informationswirtschaft Institut für Informationsverarbeitung und Informationswirtschaft Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien Augasse 2-6 A-1090 Wien, AUSTRIA Telefon: 31336/6081 E-mail: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Introduction ..…………………………………………………………………3 2. Information goods and the digital technology………………………………...4 Information goods ……………………………………………………………….4 The problem with information goods in digital form ………………………………...6 3. Digital Libraries……………………………………………………………….7 Definition ………………………………………………………………………7 Properties of Digital Libraries …………………………………………………….7 4. Digital Rights Management..………………………………………………….8 Architecture ………………………………………………………………………...………9 Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998…………………………………………...…..10 5. Strategies for publishers of IP………………………………………………..15 How digital technology affects the management of intellectual property ……………...15 6. Case Studies: What do other digital libraries do? …………………………...18 The National Academies Press …………………………………………………..18 The Academic Library ………………………………………………………….19 Dissertation.com ……….……...………………………………………………20 University of California Press and California ……………………………………..22 Digital Library's eScholarship program 7. EPub and strategies for ePub ……………………………………………….24 8. Literature ……………………………………………………………………27 -

The Marketing of Information in the Information Age Hofacker and Goldsmith

The Marketing of Information in the Information Age Hofacker and Goldsmith THE MARKETING OF INFORMATION IN THE INFORMATION AGE CHARLES F. HOFACKER, Florida State University RONALD E. GOLDSMITH, Florida State University The long-standing distinction made between goods and services must now be joined by the distinction between these two categories and “information products.” The authors propose that marketing management, practice, and theory could benefit by broadening the scope of what marketers market by adding a third category besides tangible goods and intangible services. It is apparent that information is an unusual and fundamental physical and logical phenomenon from either of these. From this the authors propose that information products differ from both tangible goods and perishable services in that information products have three properties derived from their fundamental abstractness: they are scalable, mutable, and public. Moreover, an increasing number of goods and services now contain information as a distinct but integral element in the way they deliver benefits. Thus, the authors propose that marketing theory should revise the concept of “product” to explicitly include an informational component and that the implications of this revised concept be discussed. This paper presents some thoughts on the issues such discussions should address, focusing on strategic management implications for marketing information products in the information age. INTRODUCTION “information,” in addition to goods and services (originally proposed by Freiden et al. 1998), A major revolution in marketing management while identifying unique characteristics of pure and theory occurred when scholars established information products. To support this position, that “products” should not be conceptualized the authors identify key attributes that set apart solely as tangible goods, but also as intangible an information product from a good or a services. -

The California Tech

After reading the Just don't super special media guy, check out the regular one ... bother see page 4 THE CALIFORNIA TECH P ASADENA CALIFORNIA FRIDAY M ARCH 1998 RAINED? WE ARE. THIS ISSUE 100% CONTENT FREE Adam Villani: Media Guy: Armegeddon, Part /I With the Oscars comin g up on Monday, th e question is not whether the Acadcmy failed to nominate it. You can safely put your money on L.A . Titanic will dominate th e compet iti on, but by how mu ch it will dominate COl/fidel/tial, but of the nominees I would cheer for Th e Sweet Hereafter the competition. Looking at the nominations individually, Ithink Titanic and DOlil/ie Brasco. has a decent shot to win in each of it s 14 nominated categories except Cillematography- The sheer beauty of Martin Scorsesc's marv elous Besi AClress (Kale Winslet). Even if lhere's a huge backlash agai nslthis Kill/dun may beat out Titan ic here. Conn oisseurs shou ld check out gOO-pound gorill a of a movie, It 's still got Ed iti ng. Art Direction , Origi Maborosi for a movie expressed al most solely through its cinematogra nal Dramatic Score, Costum e, Original Song, and Sound pretty much phy_ wrapped up and in the bag. While I think the 14 nominations represen ted Ediling- Titanic wins, and is the best nominated. Erro l Morris' docu the peak of its popu larity, I think we shou ld expect to see repre se ntatives mentary Fast, Cheap. and Oul of COlllroi and Peter Greenaway's spec of this very popular and technicai ly outstandi ng film take th e podium tacu lar Th e Pillow Book were the true masterpieces of editing this year. -

An Examination of Jerry Goldsmith's

THE FORBIDDEN ZONE, ESCAPING EARTH AND TONALITY: AN EXAMINATION OF JERRY GOLDSMITH’S TWELVE-TONE SCORE FOR PLANET OF THE APES VINCENT GASSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO MAY 2019 © VINCENT GASSI, 2019 ii ABSTRACT Jerry GoldsMith’s twelve-tone score for Planet of the Apes (1968) stands apart in Hollywood’s long history of tonal scores. His extensive use of tone rows and permutations throughout the entire score helped to create the diegetic world so integral to the success of the filM. GoldsMith’s formative years prior to 1967–his training and day to day experience of writing Music for draMatic situations—were critical factors in preparing hiM to meet this challenge. A review of the research on music and eMotion, together with an analysis of GoldsMith’s methods, shows how, in 1967, he was able to create an expressive twelve-tone score which supported the narrative of the filM. The score for Planet of the Apes Marks a pivotal moment in an industry with a long-standing bias toward modernist music. iii For Mary and Bruno Gassi. The gift of music you passed on was a game-changer. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Heartfelt thanks and much love go to my aMazing wife Alison and our awesome children, Daniela, Vince Jr., and Shira, without whose unending patience and encourageMent I could do nothing. I aM ever grateful to my brother Carmen Gassi, not only for introducing me to the music of Jerry GoldsMith, but also for our ongoing conversations over the years about filM music, composers, and composition in general; I’ve learned so much. -

Virtual Markets for Virtual Goods: the Mirror Image of Digital Copyright?

Harvard Journal of Law & Technology Volume 18, Number 1 Fall 2004 VIRTUAL MARKETS FOR VIRTUAL GOODS: THE MIRROR IMAGE OF DIGITAL COPYRIGHT? Peter Eckersley* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction.....................................................................................86 A. Information Anarchism and Information Feudalism..................86 B. Virtual Markets for Virtual Goods.............................................92 II. Reward Systems ............................................................................94 A. Rewards and Information Production........................................94 1. Rewards for Inventions ...........................................................95 2. Rewards for Writing and Other Copyright Works ..................97 B. Decentralized Compensation Systems: Constructing “Virtual Markets” .................................................................100 1. Network Security...................................................................102 2. Human Security.....................................................................104 3. Funding Virtual Markets .......................................................106 4. One Dollar, One Vote?..........................................................111 5. Scope: Which Information Markets Could Be Made “Virtual” (and Which Ones Matter)? ..............................112 6. The Role of Social Norms.....................................................115 III. An Economic Comparison of Virtual Markets and Digital Rights Management......................................................................116 -

3 Intellectual Property Rights for Data

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Rusche, Christian; Scheufen, Marc Research Report On (intellectual) property and other legal frameworks in the digital economy: An economic analysis of the law IW-Report, No. 48/2018 Provided in Cooperation with: German Economic Institute (IW), Cologne Suggested Citation: Rusche, Christian; Scheufen, Marc (2018) : On (intellectual) property and other legal frameworks in the digital economy: An economic analysis of the law, IW-Report, No. 48/2018, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft (IW), Köln This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190945 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Paradigms and Prisons: a Narrative of Translation and Transformation

((I V >-V ,___fs,-3*-' .0 Paradigms and Prisons: A Narrative of Translation and Transformation: My Hero's Journey from "At-Risk" Youth to Teacher/Learner In a Jail Setting Warren Albert Trimble Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education Faculty of Education, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario ©Warren Albert Trimble 2007 Abstract All life is suffering. Life is the pursuit ofhappiness. These are two foundational Buddhist dictums that, in their simplicity, I have entirely misunderstood regarding their depth, misreading them as contradictory. Indeed, my superficial interpretations led me to Thoreau's life ofquiet desperation and deep depression. We come to know and bring understanding to our lives by storying them. My own Hero's Journey, the path from my egoic selftoward the universal Self, can be understood as the resultant translations and transformations. Inevitably each of us is involved in such a story, though most are unaware of the stages along our own Hero's journey. ' Narrative honours writing as a means of knowing. The contemplative reflection allows insight into our imprisoning paradigms, beliefs, behaviours, and blind spots. My research revisits and explores nodal experiences along my Hero's Journey through 4 categories: self, society, soil, and Self. While the value of this process of narrative inquiry lay in its ability to come to know and understand one's self, perhaps its greater value is of a more universal nature. My inquiry, while adding to the body of academic educational narrative literature, may also illuminate a path to educators, students, and all interested, encouraging a response to the call of their own Hero's journey.