Behavioral Treatment of Bedtime Problems and Night Wakings In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Behavioral Insomnia of Childhood Behavioral insomnia of childhood is a common type of insomnia that can affect children as early as 6 months of age. It is seen in up to 30% of children. If left untreated, it can persist into adulthood. Insomnia can be disruptive to the child’s life and can be a problem for parents and other people they live with. This fact sheet will describe this common type of insomnia and how to treat it to improve your child’s sleep. What is behavioral insomnia of childhood? How can I make sure my child has healthy sleep? There are different types of behavioral insomnia of 1. Know how much sleep your child needs. Below are childhood as described below. guidelines on how many hours your child should sleep Sleep onset association type: Children, generally under the based on his/her age. The American Academy of age of two years of age, have a hard time falling asleep on Pediatrics and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine their own or returning back to sleep when they wake up recommend: unless there are special conditions at bedtime. For example, Age: Hours of sleep per day: they may be used to having their favorite toy next to them, 4 – 12 months 12 – 16 hours (including naps) being rocked to sleep or used to having a parent sit next 1 – 2 years 11 – 14 hours (including naps) to them in order to fall asleep. This process can be very 3 – 5 years 10 – 13 hours (including naps) demanding to the child and parent/caregiver. -

Zimmerman Chair Bedroom

BRUNSWICK ZIMMERMAN BEDROOM BRUNSWICK 7314 7318 CHEST OF DRAWERS ARMOIRE 7331 LANDSCAPE MIRROR 7324 7326 DOUBLE DRESSER TRIPLE DRESSER 7314 CHEST OF DRAWERS 56" H X 38" W X 19" D 7315 LOW CHEST OF DRAWERS 27" H X 42" W X 25" D 7318 ARMOIRE 7315 77" H X 42" W X 25" D LOW CHEST OF DRAWERS 7324 DOUBLE DRESSER 36" H X 60" W X 19" D 7326 TRIPLE DRESSER 39" H X 72" W X 19" D 7330 VERTICAL MIRROR 36" H X 43" W X 2" D 7331 LANDSCAPE MIRROR 26" H X 48" W X 2" D 7350 BRUNSWICK PANEL BED Standard Headboard 52" H Standard Footboard 18" H 7350Q BRUNSWICK PANEL BED 7360 BRUNSWICK CANOPY BED Headboard 52" / 78" H Footboard 18" / 78" H 7331 LANDSCAPE MIRROR - See pricelist for complete bed and case options w/ specs and dimensions - All drawers are standard with full access undermount soft-close glides - All cases have interior frame construction with dust-proof panels between each drawer 7360Q -All Brunswick Beds have rails BRUNSWICK CANOPY BED with hidden bolt mount systems and wooden dovetail slats All beds are available in Twin(T), Full(F), Queen(Q), California King ( C ), King (K) BRUNSWICK 7301 NIGHT TABLE 31" H X 24" W X 15" D 7303 BEDSIDE CHEST 29" H X 28" W X 15" D 7301 7303 NIGHT TABLE BEDSIDE CHEST ZIMMERMAN BEDROOM BY WWW.ZIMMERMANCHAIR.COM FRANCESCA FRANCESCA 8251K Francesca Bed 8224 Double Dresser 8201 NIGHT STAND- 3 Drawers 32"H X 26"W X 18"D 8213 LINGERIE CHEST (not shown) 56"H x 26"W x 20"D 8214 CHEST OF DRAWERS 56"H x 40"W x 20"D 8224 DOUBLE DRESSER 38"H x 60"W x 20"D 8251K FRANCESCA BED Standard Headboard 55"H 8201 Standard Footboard -

VA/Dod Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

VA/DoD CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF CONCUSSION-MILD TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY Department of Veterans Affairs Department of Defense QUALIFYING STATEMENTS The Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense guidelines are based upon the best information available at the time of publication. They are designed to provide information and assist decision making. They are not intended to define a standard of care and should not be construed as one. Neither should they be interpreted as prescribing an exclusive course of management. This Clinical Practice Guideline is based on a systematic review of both clinical and epidemiological evidence. Developed by a panel of multidisciplinary experts, it provides a clear explanation of the logical relationships between various care options and health outcomes while rating both the quality of the evidence and the strength of the recommendation. Variations in practice will inevitably and appropriately occur when clinicians take into account the needs of individual patients, available resources, and limitations unique to an institution or type of practice. Every healthcare professional making use of these guidelines is responsible for evaluating the appropriateness of applying them in the setting of any particular clinical situation. These guidelines are not intended to represent TRICARE policy. Further, inclusion of recommendations for specific testing and/or therapeutic interventions within these guidelines does not guarantee coverage of civilian sector care. Additional information on current TRICARE benefits may be found at www.tricare.mil or by contacting your regional TRICARE Managed Care Support Contractor. Version 2.0 – 2016 VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Concussion-mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prepared by: The Management of Concussion-mild Traumatic Brain Injury Working Group With support from: The Office of Quality, Safety and Value, VA, Washington, DC & Office of Evidence Based Practice, U.S. -

Bed Bug Fact Sheet

BED BUGS September 2011 Bed bugs are found worldwide. In recent years, bed bugs have been making a comeback because of changing insect control practices, pesticide resistance and increased international travel. Travel spreads them because the bugs and their eggs are easily transported in luggage, clothing, bedding, and furniture. Quick facts o Bed bugs are fast moving insects that eat mostly at night when their host is asleep. o Prefer human blood but will feed on chickens, mice, and rabbits, too. o They feed on any area of exposed skin, such as the face, neck, shoulders, arms or hands. o The bites don’t hurt, so the person usually doesn’t know that he/she has been bitten, but bed bug bites do irritate the skin. o Depending on availability of food and temperature (70-82F is optimal); it takes 5 weeks to 4 months for the maturation of a bed bug from egg to adult. o They can go 80 to 140 days without a meal. o Adults live about 10 months. Do bed bugs spread disease? o Bed bugs are not known to transmit disease; however, they can cause physical and mental stress. o A reaction to the bites can take 1– 14 days to develop, and some people have no reaction. o Bed bug bites look like mosquito, flea, and spider bites. The only way to confirm the bite is from a bed bug is to find evidence of the bugs in your bed/bedroom. What do bed bugs look like? o Adult bed bugs are oval shaped, wingless, 1/3 inch long, rusty red or mahogany color, and shaped like an apple seed. -

Contemporary DIY Four Poster Bed

Contemporary DIY Four Poster Bed Here are a few housekeeping items before you start that will make this project even easier to tackle. First, this bed needs to be assembled in the space in the bedroom it will be in. The assembled parts are larger than a doorway. I stained and waxed my wood pieces before assembling. Since the wood was already finished, I placed a heavy moving blanket on the floor to protect the wood from scratches. Time to complete: 2-3 days Lumber: 2 - 1” x 2” x 8ft poplar 16 - 1” x 3” x 6ft poplar 2 – 2” x 2” x 6ft poplar 6 - 1” x 6” x 6ft maple 3 – 2” x 2” x8ft maple 2 – 2” x 3” x 8ft maple 2 – 2” x 6” x 6ft maple 4 – 3” x 3” x 8ft maple Materials: Pocket screws 1 ¼ Pocket screws 2 ” Wood screws 1 ¼ ” Wood screws 1 ½ “ Wood glue Sand paper Stain or paint to finish Cut List: Maple 4 - 3” x 3” at 78 ¾” bed posts 2 - 2” x 2” at 60 ½“ top rails 2 - 2” x 6” at 60 ½” footboard and lower headboard planks 6 – 1” x 6” at 60 ½” headboard planks 2 – 2” x 2” at 80 ½” upper rails 2 – 2” x 4” at 80 ½” lower side rails Poplar 2 – 1’ x 2’ at 80 ½” slat cleat 1 – 2’ x 2’ at 80 ½” center support 1 – 2” x 2” at 9 ¼” center support legs 16 – 1” x 3” at 60 ½” slats Preparation Cut, sand and finish all of the maple pieces. -

Abstracts from the 50Th European Society of Human Genetics Conference: Electronic Posters

European Journal of Human Genetics (2019) 26:820–1023 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0248-6 ABSTRACT Abstracts from the 50th European Society of Human Genetics Conference: Electronic Posters Copenhagen, Denmark, May 27–30, 2017 Published online: 1 October 2018 © European Society of Human Genetics 2018 The ESHG 2017 marks the 50th Anniversary of the first ESHG Conference which took place in Copenhagen in 1967. Additional information about the event may be found on the conference website: https://2017.eshg.org/ Sponsorship: Publication of this supplement is sponsored by the European Society of Human Genetics. All authors were asked to address any potential bias in their abstract and to declare any competing financial interests. These disclosures are listed at the end of each abstract. Contributions of up to EUR 10 000 (ten thousand euros, or equivalent value in kind) per year per company are considered "modest". Contributions above EUR 10 000 per year are considered "significant". 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: E-P01 Reproductive Genetics/Prenatal and fetal echocardiography. The molecular karyotyping Genetics revealed a gain in 8p11.22-p23.1 region with a size of 27.2 Mb containing 122 OMIM gene and a loss in 8p23.1- E-P01.02 p23.3 region with a size of 6.8 Mb containing 15 OMIM Prenatal diagnosis in a case of 8p inverted gene. The findings were correlated with 8p inverted dupli- duplication deletion syndrome cation deletion syndrome. Conclusion: Our study empha- sizes the importance of using additional molecular O¨. Kırbıyık, K. M. Erdog˘an, O¨.O¨zer Kaya, B. O¨zyılmaz, cytogenetic methods in clinical follow-up of complex Y. -

Family Environment and Attitudes of Homeschoolers and Non-Homeschoolers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 323 027 PS 019 040 AUTHOR Groover, Susan Varner; Endsley, Richard C. TITLE PAmily Pnvirnnme& =na Att4turles -f Homesohoolers and Non-Homeschoolers. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 34p. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses - Master Theses (042)-- Reports nesearch/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Rearing; Comparative Analysis; Educational Attitudes; Educatioral Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; *Family Attitudes; *Family Characteristics; *Family Environment; Family Relationship; *Home Schooling; Parent Participation; Peer Relationship; *Public Schools; Socialization IDENTIFIERS RAcademic Orientation; *Value Orientations ABSTRACT This study explored differences between families with children educated at home and those with children in public schools, and examined the educational and socialization values and practices of different subgroups of homeschoolers. Subjects were 70 homeschooling parents and 20 nonhomeschooling parents who completeda questionnaire assessing parents' educational and child-rearing values and practices, and family members' social relationships outside the home. Homeschoolers were divided into groups according toreasons they gave for homeschooling: either academic reasons or reasons related to beliefs. Findings indicated that homeschooling parents had more hands-on involvement in their child's education. Home environments of academically motivated homeschoolers were more stimulating than those of homeschoolers motivated by beliefs or those of children in public schools. Academically motivated homeschooling parents expected earlier maturity and independence from children than did parents in the other groups. Homeschoolers restricted children's television viewing more than non-homeschoolers. Homeschoolers motivated by beliefs were more authoritarian and involved in church activities than parents in the other groups. (RE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Hearts Bed with 4 Poster Frame

Hearts Bed With 4 Poster Frame Assembly Instructions - Please keep for future reference 323/8130 333/9613 Dimensions Width - 197cm Depth - 94cm Height - 189cm Important - Please read these instructions fully before starting assembly If you need help or have damaged or missing parts, call the Customer Helpline: Argos = 0345 640 0800 Issue 1 - 08//10/14 Safety and Care Advice Important - Please read these instructions fully before starting assembly • Keep children and animals • We do not IMPORTANT! away from the work area, small recommend the KEEP FOR parts could choke if swallowed. use of power drill/drivers for • Make sure you have enough FUTURE inserting screws, space to layout the parts before as this could damage the unit. REFERENCE starting. Only use hand screwdrivers. • Check you have all the • During assembly do not stand • Assemble on a soft level components and tools listed on or put weight on the product, this surface to avoid damaging the the following pages. could cause damage. unit or your floor. • Remove all fittings from the • Assemble the item as close to • Parts of the assembly will be plastic bags and separate them its final position (in the same easier with 2 people. into their groups. room) as possible. • Unit weight: 20.4 kgs. Care and maintenance • Only clean using a damp cloth • From time to time check that • This product should not be and mild detergent, do no use there are no loose screws on discarded with household bleach or abrasive cleaners. this unit. waste. Take to your local authority waste disposal centre. Warnings • Regularly check and ensure • Prohibit your children from • Do not use this child’s bed if that all bolts and fittings are bouncing and jumping on the any part is broken, torn or tightened properly. -

60 Bedtime Activities

60 Bedtime Activities to promote connection and fun 1. Pick each other’s pajamas, and both parent and child put them on at the same time. 2. Have a tooth brushing party with everyone in the family complete with music and dancing. 3. Share 5 favorite things about your child with them. 4. Make up a bedtime story where someone in the family is the main character and kid has to guess which family member it is. 5. Wheelbarrow around (hold your child’s ankle’s and have them walk through their routine on their hands). 6. Play ‘Simon Says’ throughout bedtime routine. 7. Enforce a ‘No talking only singing’ rule. 8. Read a bedtime story in a silly voice. 9. Make up your own knock-knock jokes. 10. Communicate only through gestures and hand signals. 11. Pick the craziest pajamas possible. 12. Have the most serious bedtime ever. No laughing. 13. Play a board game with crazy backward rules. 14. Walk everywhere backward. 15. Try to put on your child’s pajamas while they lay on the floor deadweight. 16. Swap roles and pretend to be each other (think Parent Trap) 17. How many stuffed animals can we fit in the bed challenge? 18. Everyone picks an animal to imitate through the routine. 19. Roleplay your favorite historical character through the routine. 20. Make a ‘YouTube’ video on how to have an epic bedtime routine. 21. Listen to each other’s favorite songs together. 22. Brush each other’s teeth. 23. Race to see who gets through routine first parent or child. -

Making Life Easier: Bedtime and Naptime

Making Life Easier By Pamelazita Buschbacher, Ed.D. Illustrated by Sarah I. Perez any families find bedtime and naptime to be a challenge for them and their children. It is estimated that 43% of all chil- dren and as many as 86% of children with developmental delays experience some type of sleep difficulty. Sleep problems Bedtime Mcan make infants and young children moody, short tempered and unable to engage well in interactions with others. Sleep problems can also impact learning. When a young child is sleeping, her body is busy developing new and brain cells needed for her physical, mental and emotional development. Parents also need to feel rested in order to be nurturing and responsive to their growing and active young children. Here are a few proven tips for making Naptime bedtimes and naptimes easier for parents and children. Establish Good Tip: Sleep Habits Develop a regular time for going to bed and taking naps, and a regular time to wake up. Young children require about 10-12 hours of sleep a day (see the box on the last page that provides information on how much sleep a child needs). Sleep can be any combination of naps and night time sleep. Make sure your child has outside time and physical activity daily, but not within the hour before naptime or bedtime. Give your child your undivided and unrushed attention as you prepare her for bedtime or a nap. This will help to calm her and let her know how important this time is for you and her. Develop a bedtime and naptime routine. -

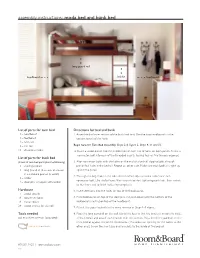

Assembly Instructions: Moda Bed and Bunk Bed

assembly instructions: moda bed and bunk bed long guard rail headboard ladder footboard List of parts for twin bed Directions for bed and bunk 1 – headboard 1. Assemble the lower section of the bunk bed first. Use the two headboards as the 1 – footboard bottom panels of the bunk. 2 – bed rails 1 – slat roll Begin here for Twin Bed Assembly. Steps 2-4, Figure 2, Steps 9, 11 and 12. 18 – decorative bolts 2. Insert a wood dowel into the middle hole of each trio of holes on both panels. Screw a connector bolt into each of the threaded inserts, leaving four or five threads exposed. List of parts for bunk bed ( 2 sets of twin bed parts plus the following) 3. Align connector bolts with the holes on the end of a bedrail, slipping bolts through 1 – short guardrail pre-drilled holes in the bedrail. Repeat on other side. Make sure each bedrail is tight up 1 – long guardrail (4 screws enclosed against the panel. in cardboard pad on bracket) 4. Through the large hole in the side of the bedrail, slip one metal collar over each 1 – ladder connector bolt. Use the ball end Allen wrench to start tightening each bolt, then switch 4 – steel pins wrapped with ladder to the short end to finish tightening completely. Hardware 5. Insert steel pins into the holes on top of the headboards. 4 – wood dowels 8 – connector bolts 6. Place footboards on top of the steel pins and push down until the bottom of the 8 – metal collars footboard is resting on top of the headboard. -

Sleep and Bedtime Problems Brief Interventions

BRIEF INTERVENTIONS: TREATING SLEEP AND BEDTIME PROBLEMS BI-PED PROJECT (BRIEF INTERVENTIONS: PEDIATRICS) Emotional Health Committee Maryland Chapter American Academy of Pediatrics Steven E. Band, Ph.D. Most infants, toddlers, and children with sleep problems are normal children who have simply learned maladaptive sleep patterns and habits. Their sleep and bedtime problems can be addressed easily and quickly. Normal Sleep Patterns Sleep occurs in repeating cycles of REM and non-REM throughout the night Non-REM sleep divides into four stages, from drowsiness to very deep sleep Awakenings and arousals are normal Deepest sleep usually comes at the beginning and the end of the night There are developmental changes in children’s need for sleep Common Sleep Problems Bedtime resistance or stalling Difficulty falling asleep Nighttime awakenings Feedings during the night Parasomnias/ partial awakenings (sleep talking, sleep walking, sleep terrors) Assessing Sleep and Bedtime Problems Determine whether the sleep problems represent the learning of maladaptive sleep patterns and habits or signify more severe and pervasive emotional problems Children with ADHD, anxiety, depression, autism or who are on certain medications may be more likely to have sleep problems If a child’s sleep patterns are causing a problem for his/her parents or for that child, then there is a sleep problem Conduct a parent interview, including a history of the child’s sleep and bedtime patterns, a history of sleep problems, and a history of parental attempts to