Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

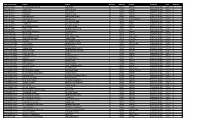

Registration No. Name Father Gender Roll No. Result Program Part

Registration No. Name Father Gender Roll No. Result Program Part Archive 2016-LK-4619 MUHAMMAD JUNAID ALIF SHAH M 17001 269.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4787 ABDULLAH ABDUR RAZIQ M 17002 319.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2013-LK-3618 NOWSHAD GUL RAHIM M 17003 268.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2013-LK-3519 LUQMAN BAKHT ULLAH M 17004 287.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4918 NAWAB ZADA SHAH WALI KHAN M 17005 276.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2015-LK-4182 RAHMAN ALI ABDUL LATIF M 17006 Re:Eng (C),SW, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4701 NIAZ MUHAMMAD HAJI HAZRAT MIR M 17007 Re:Ur, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4716 AAMIR ALI SAID WALI KHAN M 17008 Re:Ur, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4624 MUHAMMAD AYAZ GUL ROZ KHAN M 17009 Re:SW, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4567 RAFI ULLAH MUHAMMAD AYUB M 17010 127 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4791 MUHAMMAD SAQIB SHAKIR ULLAH M 17011 300.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2014-JCK-1241 NOOR SAID JAN SAID M 17012 264.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2015-JCK-1570 MUHAMMAD NOOR AQAL MAN SHAH M 17013 Re:Eng (C), Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-JCK-1706 SAMOOD REHMAN JANAT KHAN M 17014 Re:Socio, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-FCGH-1995 SHAMA HAJI RASHID KHAN F 17015 296.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2013-FCGH-1640 UJALA AMIN MUHAMMAD AMIN F 17016 Absent:Law, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-FCGH-2042 KHUSHNUMA NASIR KHAN F 17017 294.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-FCGH-1942 SABIHA BIBI MUHAMMAD RASOOL F 17018 330.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-FCGH-1968 HINA YAQOOB MUHAMMAD -

Db List for 03-12-2020(Thursday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR THURSDAY, 03 DECEMBER, 2020 MR. JUSTICE QAISER RASHID KHAN, ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE SYED ARSHAD ALI MOTION CASES 1. W.P 4627- Hameed ullah Muhammad Inam Yousafzai P/2020(Detenue V/s Muhammad Zubair State Deputy Attorney General, Kamran Khan) Ullah, Shahzad Anjum, Mr. Muhammad Nawaz Aalam, Mirza Khalid Mahmood., Writ Petition Branch AG Office, Salman Khan 5259 (Focal Person IGP) 2. W.P 4684-P/2020() Izhar Hussain Khan Zada Ajmal Zeb Khan V/s Incharge Interment Center Deputy Attorney General, Shahzad Anjum, Mr. Muhammad Nawaz Aalam, Mirza Khalid Mahmood., Writ Petition Branch AG Office, Gulab Hussain 3. W.P 5053-P/2020 Awal Khan Syed Masood Shah with CM V/s 2187/2020(Detenu Govt of KPK Writ Petition Branch AG Office, e Muhammad Salman Khan 5259 (Focal Person Irfan) IGP) 4. COC 618- Mst. Kheratt Gula Hayatullah shah, Kashan Abdullah P/2020(in WP 490- V/s P/2015 (Against Minsitry of States Deputy Attorney General, order HCJ,V)) Muhammad Ahmad Khan, Ms. Sehrish Mazari, Writ Petition Branch AG Office 5. Rev in WP 144- Touseef ur Rehman Shahid Naseem Khan Chamkani P/2020(in WP V/s 2932-P/2020 Govt of KPK Hidayatullah (Focal Person), (Auther is Muhammad Khalid Matten, Writ Mr.Justice Syed Petition Branch AG Office Arshad Ali)) IT Branch Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 82 Video Link only available in Court # 1,2,3 and 4 _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR THURSDAY, 03 DECEMBER, 2020 MR. -

Mardan (Posts-1) Scoring Key: Grade Wise Marks 1St Div: 2Nd Div: 3Rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1

At least 2nd Division Master in Social Sciences (Social Work/ Sociology will be preferred) District: Mardan (Posts-1) Scoring Key: Grade wise marks 1st Div: 2nd Div: 3rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1. (a) Basic qualification Marks 60 S.S.C 15 11 9 Date of Advertisement:- 22-08-2020 2. Higher Qualification Marks (One Step above-7 Marks, Two Stage Above-10 Marks) 10 F.A/FSc 15 11 9 SOCIAL CASE WORKER (BPS-16) 3. Experience Certificate 15 BA/BSc 15 11 9 4. Interviews Marks 8 MA/MSc 15 11 9 5. Professional Training Marks 7 Total;- 60 44 36 Total;- 100 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR APPOINTMENT TO THE POST OF SOCIAL CASE WORKER BPS-16 BASIC QUALIFICATION Higher Qual: SSC FA/FSC BA/BSc M.A/ MS.c S. # on Name/Father's Name and address Total S. # Appli: Remarks Domicile Malrks= 7 Total Marks Marks Marks Marks Marks Date of Birth Qualification Division Division Division Division Marks P.HD Marks M.Phil Marks of Experience Professional/Training One Stage Above 7 Two Two Stage Above 10 Interview Marks 8 Marks Year of Experience 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Mr. Farhan Raza S/O Abid Raza, Koz Kaly Madyan, P.O Madyan, Tehsil and District Swat, 0314- Mphil Agriculture Rual 71 3/2/1992 Swat 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 10 70 70 9818407 Sociology Mr. Muhammad Asif Khan S/O Muhammad Naeem Khan, Rahat Abad Colony, Bannu Road P.O PHD Business 494 16-04-1990 Lakki Marwat 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 10 70 70 Sheikh Yousaf District D.I.Khan. -

FATA) Et De La Province De Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP) : Frontier Corps, Frontier Constabulary, Levies, Khasadar Forces

PAKISTAN 27 juillet 2017 Les organisations paramilitaires des Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA) et de la province de Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP) : Frontier Corps, Frontier Constabulary, Levies, Khasadar Forces Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf ], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Résumé : Quatre types d’organisations paramilitaires sont déployées dans les FATA et la PKP. -

University of Peshawar Prospectus 2018-19

University of Peshawar Prospectus 2018-19 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION The City of Peshawar 4 Vice Chancellor Message 6 Administration 7 Directorate of Admissions 9 Student Financial Aid Office 10 Academic Programmes 14 Campus Life 15 The Bara Gali Summer Camp 16 Brief Features of Constituent 17 Colleges STUDENTS FACILITIES 19 READING FACILITIES 21 IT FACILITIES 25 HOW TO APPLY? Undergraduate Programme (BS-4 30 Postgraduate Programme (Master-2 39 Years) Years) Higher Studies Programme 52 (M.Phil/MS/Ph.D) FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITY Archaeology 55 Art & Design 57 English & Applied Linguistics 59 History 61 Philosophy 63 Tourism & Hotel Management 65 FACULTY OF ISLAMIC & ORIENTAL STUDIES Arabic 68 Islamiyat 70 Pashto 72 Pashto Academy 74 Persian 76 Seerat Studies 78 Urdu 80 FACULTY OF LIFE & ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Biotechnology & Microbiology 83 Botany 87 Chemical Sciences 89 Disaster Management 92 Environmental Science 97 Geography 100 Geology 102 Pharmacy 104 Plant Biodiversity 106 Urban & Regional Planning 110 Zoology 113 Page 1 University of Peshawar Prospectus 2018-19 FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT & INFORMATION SCIENCES Journalism & Mass 116 Library & Information Sciences 119 Communication Institute of Management Studies 121 Quaid-e-Azam College of Commerce 126 (IMS) FACULTY OF NUMERICAL & PHYSICAL SCIENCES Computer Science 129 Electronics 133 Mathematics 135 Physics 137 Statistics 141 FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Criminology 144 Economics 146 Education & Research (I.E.R) 148 Gender Studies 152 International Relations (IR) 154 Law College 156 Peace -

“Global Terrorism Index: 2015.” Institute for Economics and Peace

MEASURING AND UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF TERRORISM Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP has offices in Sydney, New York and Mexico City. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organizations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org SPECIAL THANKS to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) headquartered at the University of Maryland for their cooperation on this study and for providing the Institute for Economics and Peace with their Global Terrorism Database (GTD) datasets on terrorism. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 ABOUT THE GLOBAL TERRORISM INDEX 6 1 RESULTS 9 Global Terrorism Index map 10 Terrorist incidents map 12 Ten countries most impacted by terrorism 20 Terrorism compared to other forms of violence 30 2 TRENDS 33 Changes in the patterns and characteristics of terrorist activity 34 Terrorist group trends 38 Foreign fighters in Iraq -

PAKISTAN: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

PAKISTAN: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa T A J I K I S T A N ± Zhuil ! Lasht ! Moghlang Nekhcherdim Chitral ! ! Morich ! Nichagh ! Muligram ! Druh ! Rayan ! Brep ! Zundrangram ! Garam Chashma Chapalli ! Mastuj ! Drasan !Bandok ! Arkari Sanoghar Nawasin ! ! Ghari ! Lon Afsik Besti ! ! ! Nichagh ! Dung Harchin ! Gushten Beshgram ! ! Laspur Imirdin ! ! Mogh Maroi ! ! Darband ! Koghozi Chitral ! Serki Singur ! ! Goki Chitral Shahi ! P.A.K !!! Nekratok ! ! Kuru Atchiku Paspat ! ! ! Brumboret ! Tar ! Kalam Gabrial ! Drosh Banda-i- ! Kalam Sazin ! ! Dong Kalkot Utrot ! Mirkhani ! Halil ! ! ! Lamutai Harianai ! Dammer Babuzai Nissar ! Sur Dassu ! Biar Swat Banda ! Biaso ! Dassu !! Gujar !! Banda Arandu ! Chodgram Chochun ! Dir ! Kohistan ! Ayagai Upper ! Bahrain Dir Pattan Dadabund Dir Banda ! Bahrain ! ! ! !! Ushiri ! ! Chachargah Chutiatan Daber ! ! ! Baiaul Barawal KHYBER Patan Bandai ! ! Kwana Matta ! Gidar Fazildin-Ki-Basti Nachkara Sebujni PAKHTUNKHWA ! ! A F G H A N I S T A N ! ! Khandak Palas Shenkhor ! ! Matta Bara ! Saral ! Aligram ! Domela Baihk ! Khararai Drush ! ! ! Wari Khel Rambakai Barwa ! Domel ! ! Alpuri ! Burawai Dardial Khwazakhela ! ! Samar ! Khal Bar Shang ! Kaga Bagh ! !Alamganj Kotka!i!! Alpuri ! ! Salarzai Lower ! ! Pokal ! ! Alai ! Batagram Dadai Tehsil Dir Kab!al Charbagh Shangla ! ! Mamund !Mian ! Bisham Kili !! Galoch ! ! Aspanr !Dandai Balakot ! Khalozai ! ! Alagram Chiksar ! ! ! ! Khongi Saidu Sharif!! Mongora ! Lari ! ! ! ! Khar Utman ! ! Nawagai Anangurai ! ! ! Khel ! Tim!ergara !!! Jatkol Panjnadi Bar ! Khar !Babuzai ! ! -

Daily List for Wednesday, 26 February, 2020

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT BENCH, DERA ISMAIL KHAN DAILY LIST FOR WEDNESDAY, 26 FEBRUARY, 2020 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE ABDUL SHAKOOR Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 1. Cr.Misc 44/2020() Muhammad Mumtaz Ahsan Bilal Langrah V/s State etc 2. RFA 68/2019() Shaman Khel Tribe thr. Haji Muhammad Mohsin Ali,Hadayat Banoot Khan Ullah Mehsod, Sajad Ahmad V/s Shami Nazar Khel Tribe thr. Dilawar Khan etc 3. RFA 70/2019() Sheikh Fateh Muhammad Khan Fazal ur Rehman Baloch V/s Sheikh Muhammad Nasir Jan 4. RFA 75/2019() Mahrban Sana Ullah Shamim Gandapur, V/s Kaneez Batool Govt. of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa etc 5. RFA 76/2019() Khan Doran etc Sana Ullah Shamim Gandapur, V/s Kaneez Batool Govt. of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa etc 6. RFA 81/2019() Ghulam Yasin thr. LRs Shakeel Ahmad Katti Khel, V/s Muhammad Jehangir Muhammad Zahid etc MIS Branch,Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 9 Report Generated By: C f m i s _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR WEDNESDAY, 26 FEBRUARY, 2020 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE ABDUL SHAKOOR Court No: 1 MOTION CASES 7. RFA 82/2019 CM Nadir Khan etc Muhammad Mohsin Ali NO.66/2019() V/s Chairman WAPDA etc 8. W.P 1099/2019 Rasoolan Begum etc Saleem Ullah Khan Ranazai, INTERIM RELIEF() V/s Tanvir Ahmad Baloch Malik Mandous etc 9. W.P 1133/2019 Jehangir Khan etc Zainul Abideen Afridi INTERIM RELIEF() V/s Tanvir Saqlain etc 10. W.P 1135/2019 Inam Ullah Hameed Ullah CM V/s NO.1253/2019() Mst. Bibi Muzaina etc 11. -

A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub- Variety of Pakistani English Under the Influence of Pashto

A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub- Variety of Pakistani English under the Influence of Pashto By Ayyaz Mahmood NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES ISLAMABAD December 2013 A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub-Variety of Pakistani English under the Influence of Pashto By Ayyaz Mahmood A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In English Linguistics To FACULTY OF HIGHER STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES, ISLAMABAD December 2013 Ayyaz Mahmood, 2013 iii THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Higher Studies: Thesis Title: A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub-Variety of Pakistani English under the Influence of Pashto Submitted By: Ayyaz Mahmood Name of Student Registration #: 269-MPhil/Eng/2007(Jan) Doctor of Philosophy Degree Name in Full English Linguistics Name of Discipline Professor Dr Aziz Ahmad Khan Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Professor Dr Shazra Mnnawer Name of Dean (FHS) Signature of Dean (FHS) Maj General (R) Masood Hasan Name of Rector Signature of Rector Date iv CANDIDATE DECLARATION FORM I Mr Ayyaz Mahmood Son of Mr Sultan Mahmood Registration # 269-MPhil/Eng/2007 Discipline: English Linguistics Candidate of Doctor of Philosophy at the National University of Modern Languages do hereby declare that the thesis titled A Critical Study of the Phonology of a Sub-Variety of Pakistani English under the Influence of Pashto submitted by me in partial fulfillment of PhD degree in the Department of Advanced Integrated Studies and Research, NUML, is my original work, and has not been submitted or published earlier. -

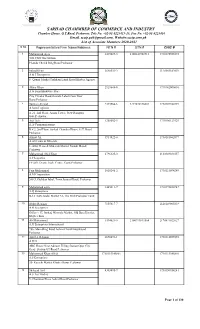

Final Voter List (Associate) 2020-21

SARHAD CHAMMBER OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY Chamber House, G.T.Road, Peshawar. Tele No. +92-91-9225413-15, Fax No. +92-91-9225416 Email. [email protected], Website:sccip.com.pk List of Associate Members 2020-2021 S No Representative/Firm Name/Address NTN # STN # CNIC # 1 Mohammad Ayaz 3419029-5 2100341902916 1730175925573 3GS CNG Gas Station Phandu Chowk Ring Road Peshawar 2 Irshad Khan 3648532-2 2120303182039 A & J Enterprises 8- Qaumi Market Torkham Landi Kotal Khyber Agency 3 Akbar Khan 2929648-0 1730162000601 A & Sons Hardware Store City Circular Road,Outside Lahori Gate,Near Bano,Peshawar 4 Tanveer Ahmad 2393366-6 3277876146001 1730107480749 A Sons Logistics A-21, 2nd Floor, Arsala Tower, New Rampura Gate,Peshawar 5 Asif Aziz 1288602-5 1730106123929 A.A Communications R # 2, 2nd Floor, Sarhad Chamber House, G.T. Road, Peshawar. 6 Azmat Ali 3914822-0 1730181862877 A.Ali Gems & Minerals 1- Swat Gems & Minerals Market Namak Mandi Peshawar 7 Muhammad Abid Khan 2796325-0 2120349031057 A.F Logistics FF-269, Deans Trade Centre, Cantt,Peshawar 8 Faiz Muhammad 1018246-2 1730115094249 A.M.Corporation 588/3, Gulshan Iqbal, Town,Jamrud Road, Peshawar 9 Mohammad asim 1445611-7 1730192426947 A.Q Enterprises B-12 Satta Gadai Market 32- The Mall Peshawar Cantt 10 Abdur Rehman 7155817-7 2120149805839 A.R Enterprises Office # 17, Ittehad Minerals Market, Old Bara District, Khyber Bara 11 Ali Muhammad 3394021-5 2100999811564 2170891022627 A.R Enterprises International 786- Main Ring Road Achini Chowk Hayatabad Peshawar 12 Aziz Ur Rehman 2670691-1 1730114035959 -

Islamabad, Thursday, December 31, 2020 Part Iii

1 ISLAMABAD, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 31, 2020 PART III Other Notifications, Orders, etc. GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINAT SECRETARIAT (Cabinet Division) NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 24th December, 2020 No. 5/2/2020-Awards-II.—The President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer Pakistan Civil Awards on the following Pakistani and Foreign dignitaries on the occasion of the Independence Day, 14th August, 2020:— S. No. Name of Awardee Field I. NISHAN-I-IMTIAZ 1. Mr. Zahoor-ul-Akhlaq (Shaheed), Arts(Painting/Sculpture) (Posthumous), Studio, 90-Upper Mall, Lahore. Domicile: Sindh 1763(1—31) Price: Rs. 40.00 [6657(2020)/Ex. Gaz.] 1763(2) THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., DEC. 31, 2020 [PART III S. Name of Awardee Field No. 2. Mr. Muhammad Jameel Khan Jalibi Literature (Critic/Historian) (Dr. Jameel Jalibi) (late), (Posthumous), 32-B, Central Avenue, Phase-II, Defence Housing Authority, Karachi. Domicile: Sindh 3. Mr. Ahmad Faraz(late), Literature (Poetry) (Posthumous), House No.2-B, Hali Road, Westridge, Rawalpindi. Domicile: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 4. Prof. Dr. Anwar-ul-Hassan Gilani, Science (Pharmaceutical Vice-Chancellor, Sciences) The University of Haripur, Hattar Road, Haripur. Domicile: Sindh 5. Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah, Public Service A-1, Custom Colony, Satluj Block, Allama Iqbal Town, Lahore. Domicile: Punjab III. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 6. Mr. Wonhaeng (Lee Kyu Jeong), Services to Pakistan C/O Embassy of Pakistan, Seoul, South Korea (Republic of Korea). Country: South Korea PART III] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA DEC. 31, 2020 1763(3) S. Name of Awardee Field No. 7. Ms. Salma Ataullahjan, Services to Pakistan 177-Fundy Bay Blvd, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. -

Socio-Economic Factors Affecting Journalists: a Case Study of Southern Districts Based Journalists of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Socio-Economic factors affecting journalists: A case study of Southern districts based journalists of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Submitted By Nasir Iqbal Roll No. 02 Session: 2013-2015 Supervised By Dr. Abdul Wajid Khan Department of Media Studies The Islamia University of Bahawalpur Table of Contents Sr. No. Contents 1. Table of Contents 2. List of abbreviation 3. Certificate 4. Acknowledgment 5. Declaration of Originality 6. Supervisor’s Declaration 7. Abstract CHAPTER 1 Introduction-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 1.1. Background/terms and definitions------------------------------------------------------2 1.2. Statement of the problem-----------------------------------------------------------------7 1.3. Objectives of the study-------------------------------------------------------------------7 1.4. Significance of the Study-----------------------------------------------------------------8 1.5. The impediments of the journalist ------------------------------------------------------9 1.6. The impediments faced by the journalists in line of their reporting --------------10 1.7. General Assumption---------------------------------------------------------------------10 CHAPTER 2 Literature Review Literature Review----------------------------------------------------------------------------11 Summary--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------24 CHAPTER 3 Theoretical Framework 3.1 Hypothesis-----------------------------------------------------------------------------26