Afghanistan's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

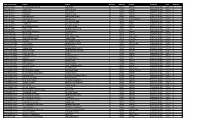

Registration No. Name Father Gender Roll No. Result Program Part

Registration No. Name Father Gender Roll No. Result Program Part Archive 2016-LK-4619 MUHAMMAD JUNAID ALIF SHAH M 17001 269.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4787 ABDULLAH ABDUR RAZIQ M 17002 319.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2013-LK-3618 NOWSHAD GUL RAHIM M 17003 268.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2013-LK-3519 LUQMAN BAKHT ULLAH M 17004 287.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4918 NAWAB ZADA SHAH WALI KHAN M 17005 276.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2015-LK-4182 RAHMAN ALI ABDUL LATIF M 17006 Re:Eng (C),SW, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4701 NIAZ MUHAMMAD HAJI HAZRAT MIR M 17007 Re:Ur, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4716 AAMIR ALI SAID WALI KHAN M 17008 Re:Ur, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4624 MUHAMMAD AYAZ GUL ROZ KHAN M 17009 Re:SW, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4567 RAFI ULLAH MUHAMMAD AYUB M 17010 127 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-LK-4791 MUHAMMAD SAQIB SHAKIR ULLAH M 17011 300.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2014-JCK-1241 NOOR SAID JAN SAID M 17012 264.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2015-JCK-1570 MUHAMMAD NOOR AQAL MAN SHAH M 17013 Re:Eng (C), Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-JCK-1706 SAMOOD REHMAN JANAT KHAN M 17014 Re:Socio, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-FCGH-1995 SHAMA HAJI RASHID KHAN F 17015 296.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2013-FCGH-1640 UJALA AMIN MUHAMMAD AMIN F 17016 Absent:Law, Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-FCGH-2042 KHUSHNUMA NASIR KHAN F 17017 294.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-FCGH-1942 SABIHA BIBI MUHAMMAD RASOOL F 17018 330.00 Bachelor of Arts Part-II 0 2016-FCGH-1968 HINA YAQOOB MUHAMMAD -

Respons Afghanistan: Sikkerhetssituasjonen I Provinsen Uruzgan

Respons Afghanistan: Sikkerhetssituasjonen i provinsen Uruzgan • Geografi, befolkning og konfliktkontekst • Konfliktdynamikk og konfliktnivå i provinsen • Sivile tap og skader som følge av konfliktrelatert vold • Internt fordrevne (IDPer) Innledning og kommentarer om kildegrunnlag Denne responsen er del av en serie notater og responser om sikkerhetssituasjonen i 15 ulike provinser i Afghanistan, som er under utarbeidelse av Landinfo høsten/vinteren 2016 og våren 2017 på oppdrag for Utlendingsdirektoratet (UDI). Responsen omhandler sikkerhetssituasjonen i Uruzgan-provinsen,1 og har et særlig fokus på situasjonen for sivilbefolkningen. Det er lagt spesiell vekt på siste halvdel av 2016 og første kvartal av 2017. Sikkerhetssituasjonen i Afghanistan er flytende og uoversiktlig, og kan endre seg raskt. Det er utfordrende å skaffe pålitelig informasjon og sammenlignende datamateriale over tid. Dette gjelder både for områder der det er pågående kamper og hvor tilgangen til kilder og informasjon er liten, og for områder der det generelt foreligger lite informasjon på grunn av områdets begrensede relevans i en større politisk, sikkerhets- eller samfunnsmessig kontekst. Landinfo benytter informasjon fra et bredt spekter av kilder; fra internasjonale og nasjonale organisasjoner, til myndigheter og media. Samtidig er det Landinfos erfaring at ved dybdeanalyse av enkelte provinser og spesifikke tema, kan det være vanskelig å få et så bredt kildegrunnlag som ønskelig. Av sikkerhetsmessige hensyn, er enkelte kilder anonymisert. Begrenset kildetilfang -

Db List for 03-12-2020(Thursday)

_ 1 _ PESHAWAR HIGH COURT, PESHAWAR DAILY LIST FOR THURSDAY, 03 DECEMBER, 2020 MR. JUSTICE QAISER RASHID KHAN, ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE & Court No: 1 BEFORE:- MR. JUSTICE SYED ARSHAD ALI MOTION CASES 1. W.P 4627- Hameed ullah Muhammad Inam Yousafzai P/2020(Detenue V/s Muhammad Zubair State Deputy Attorney General, Kamran Khan) Ullah, Shahzad Anjum, Mr. Muhammad Nawaz Aalam, Mirza Khalid Mahmood., Writ Petition Branch AG Office, Salman Khan 5259 (Focal Person IGP) 2. W.P 4684-P/2020() Izhar Hussain Khan Zada Ajmal Zeb Khan V/s Incharge Interment Center Deputy Attorney General, Shahzad Anjum, Mr. Muhammad Nawaz Aalam, Mirza Khalid Mahmood., Writ Petition Branch AG Office, Gulab Hussain 3. W.P 5053-P/2020 Awal Khan Syed Masood Shah with CM V/s 2187/2020(Detenu Govt of KPK Writ Petition Branch AG Office, e Muhammad Salman Khan 5259 (Focal Person Irfan) IGP) 4. COC 618- Mst. Kheratt Gula Hayatullah shah, Kashan Abdullah P/2020(in WP 490- V/s P/2015 (Against Minsitry of States Deputy Attorney General, order HCJ,V)) Muhammad Ahmad Khan, Ms. Sehrish Mazari, Writ Petition Branch AG Office 5. Rev in WP 144- Touseef ur Rehman Shahid Naseem Khan Chamkani P/2020(in WP V/s 2932-P/2020 Govt of KPK Hidayatullah (Focal Person), (Auther is Muhammad Khalid Matten, Writ Mr.Justice Syed Petition Branch AG Office Arshad Ali)) IT Branch Peshawar High Court Page 1 of 82 Video Link only available in Court # 1,2,3 and 4 _ 2 _ DAILY LIST FOR THURSDAY, 03 DECEMBER, 2020 MR. -

Kabul Municipality

د اﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎن اﺳﻼﻣﯽ ﺟﻤﻬﻮری دوﻟﺖ دوﻟﺖ ﺟﻤﻬﻮری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ اﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎن Kabul Municipality ﺩ ﺳﻴﻤﻪ ﻳﻴﺰﻭ ﺍﺭﮔﺎﻧﻮﻧﻮ ﺧﭙﻠﻮﺍﮐﻪ ﺍﺩﺍﺭﻩ ﺍﺩﺍﺭﻩ ﻣﺴﺘﻘﻞ ﺍﺭﮔﺎﻧﻬﺎي ﻣﺤﻠﻲ Government of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Independent Directorate of Local Governance THE STATE OF AFGHAN CITIES 2015 MINISTER’S FOREWORD Ministry of Urban Development Affairs Cities have great potential to improve livelihoods, drive economic growth and provide safe and affordable housing and adequate services. With continued urbanisation in Afghan cities occurring in the next few decades, there is a great opportunity to promote urban development that is sustainable, equitable and a catalyst for economic growth. The priorities of the National Unity Government of Afghanistan for the urban sector are very clear. The ‘Realizing Self-Reliance’ Framework presented at the London Conference on Afghanistan in 2014 explicitly stated cities are to be drivers of economic development. The Ministry of Urban Development Affairs (MUDA) is currently leading the drafting of an Urban National Priority Programme (U-NPP) and associated comprehensive urban development programme. Together these will lay the foundations for a sustainable urban future. However in Afghanistan, basic information for urban areas does not exist, is outdated, or not shared. As a result, MUDA has been challenged to pro-actively guide the growth of Afghanistan’s cities and harness urbanisation as a driver of development. This State of Afghan Cities 2014/15 report and associated dataset is already providing essential inputs to these ongoing processes. It will ensure the outcomes are pragmatic and reflect the ground realities across the country. I sincerely thank all programme partners, the Government of Australia, and UN-Habitat for supporting MUDA to implement this programme. -

Warlords, the United States, and the State of Anarchy in Afghanistan

Central European Journal of Politics Volume 7 (2021), Issue 1, pp. 46–75 ARTICLE Warlords, the United States, and the state of anarchy in Afghanistan AHMAD SHAH AZAMI*1 * Department of International Relations and European Studies, Faculty of Social Studies, Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic Abstract As part of its “War on Terror”, the United States (US) provided immense sums of money and advanced equipment to Afghan warlords in order to defeat and dismantle the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. Nearly two decades after the 2001 US-led intervention in Afghanistan that toppled the Taliban regime, the US continues supporting the warlords in various ways. As the intervention was also aimed at establishing a functioning state and reconstruction of the war-torn country, the US needed the support of local warlords to achieve its goals. However, over time, warlords and warlordism became a major challenge to the post- Taliban state-building project and in many ways undermined the overall security and the state monopoly on violence. These warlords, who had been mostly expelled and defeated by the Taliban regime, returned under the aegis of the B52 bombers, recaptured parts of the country and reestablished their fiefdoms with US support and resources. They not only resist giving up the power and prestige they have accumulated over the past few years, but also hamper the effort to improve governance and enact necessary reforms in the country. In addition, many of them run their private militias and have been accused of serious human rights abuses as well as drug trafficking, arms smuggling, illegal mining and extortion in the areas under their control or influence. -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Today's PDF Version

www.facebook.com/thekabultimes twitter.com/thekabultimes E-mail:[email protected] thekabultimes.gov.af Hoot 04, 1397 HS Saturday, February 23, 2019 Afghans USD 01 GBP 01 INR 1000 PKR 1000 EUR 01 IRR 1000 AED 01 fortunate, as productive new AFN 75.40 AFN 97.65 AFN 1055 AFN 539 AFN 85.18 AFN 6 AFN 20.28 year on the way President Ghani meets his Turkmen President Ghani chairs high economic council meeting counterpart in Ashgabat KABUL: Chaired by Presi- granting the contract to the re- were not clear, asking for clari- dent Mohammad Ashraf Ghani, spective company. After overall fication of modality of number- the meeting of high economic discussion in connection with ing for the bidding companies. council was held at Arg’s Cha- the company’s request, mem- President Ghani instructed na- har Chenar Palace. bers of the council asked for tional procurement authority to In the meeting, issues as further information in this re- cooperate with ministry of SODEVCO’s request for pro- gard. mines and petroleum in con- cessing and exporting chromite Meanwhile, the country’s nection with numbering and to outside, bidding process of President said that the amount evaluation of the companies. Nangarhar talc project, trans- of the company’s current invest- Afterwards, transferring ferring of possession of Wasel ment, management system and plan of Wasel Telecom’s license Telecom to Alkozay Group Com- its legal and economic aspects possession to Alkozay Group panies complex and getting should be clarified so that deci- Companies complex was deliv- fixed sum as non-metallic sion would be made in this re- ered by minister of telecommu- things’ issuance right were dis- gard. -

Mardan (Posts-1) Scoring Key: Grade Wise Marks 1St Div: 2Nd Div: 3Rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1

At least 2nd Division Master in Social Sciences (Social Work/ Sociology will be preferred) District: Mardan (Posts-1) Scoring Key: Grade wise marks 1st Div: 2nd Div: 3rd Div: Age 25-35 Years 1. (a) Basic qualification Marks 60 S.S.C 15 11 9 Date of Advertisement:- 22-08-2020 2. Higher Qualification Marks (One Step above-7 Marks, Two Stage Above-10 Marks) 10 F.A/FSc 15 11 9 SOCIAL CASE WORKER (BPS-16) 3. Experience Certificate 15 BA/BSc 15 11 9 4. Interviews Marks 8 MA/MSc 15 11 9 5. Professional Training Marks 7 Total;- 60 44 36 Total;- 100 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR APPOINTMENT TO THE POST OF SOCIAL CASE WORKER BPS-16 BASIC QUALIFICATION Higher Qual: SSC FA/FSC BA/BSc M.A/ MS.c S. # on Name/Father's Name and address Total S. # Appli: Remarks Domicile Malrks= 7 Total Marks Marks Marks Marks Marks Date of Birth Qualification Division Division Division Division Marks P.HD Marks M.Phil Marks of Experience Professional/Training One Stage Above 7 Two Two Stage Above 10 Interview Marks 8 Marks Year of Experience 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Mr. Farhan Raza S/O Abid Raza, Koz Kaly Madyan, P.O Madyan, Tehsil and District Swat, 0314- Mphil Agriculture Rual 71 3/2/1992 Swat 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 10 70 70 9818407 Sociology Mr. Muhammad Asif Khan S/O Muhammad Naeem Khan, Rahat Abad Colony, Bannu Road P.O PHD Business 494 16-04-1990 Lakki Marwat 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 1st 15 10 70 70 Sheikh Yousaf District D.I.Khan. -

FATA) Et De La Province De Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP) : Frontier Corps, Frontier Constabulary, Levies, Khasadar Forces

PAKISTAN 27 juillet 2017 Les organisations paramilitaires des Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA) et de la province de Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP) : Frontier Corps, Frontier Constabulary, Levies, Khasadar Forces Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf ], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Résumé : Quatre types d’organisations paramilitaires sont déployées dans les FATA et la PKP. -

Suicide Blast Kills 19 at Mosque in Saudi Arabia

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:IX Issue No:287 Price: Afs.15 SATURDAY . MAY 23 . 2015 -Jawza 02, 1394 HS www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes American University of Afghanistan NDS-ISI deal officially NDS foils provides window to terror bid in awards honorary doctorate to Karzai Pakistan s interference Kabul AT News Report NO DOUBT, AFGHANISTAN IS IMPROVING TOWARDS DEVELOPMENT AND A BRIGHTER FUTURE, BUT IT NEEDS AT News Report jointly against that spy agencies MORE STRUGGLES THE YOUNG GENERATION, PARTICULARLY THE EDUCATED ONES of enemy. If the agreement points KABUL: The Hizb-i-Ensijam out to intelligence agency of India KABUL: National Directorate of Milli Afghanistan National Sol- then it is not justifiable that the Security (NDS) claimed to have AT News Report idarity Party of Afghanistan NDS along with Pakistan fight thwarted a terror bid in Kabul. against India s RAW. India is stra- The NDS in a statement is- KABUL: Former President Ha- (NSPA) on Friday said the memorandum of understanding tegic partner of Afghanistan and sued on Friday said that opera- mid Karzai on Friday attended more than that, there is no rift tives of the spy agency arrested a graduation ceremony of bachelor (MoU) recently signed between the National Directorate of Secu- between Kabul and New Delhi. suspected terrorist who wanted and master students of American In the meantime the NSPA to detonate an explosive laden University of Afghanistan rity (NDS) and Pakistani intelli- gence agency has officialized in- also hints at another part of the vehicle in one of the key areas of (AUAF), his office said in a state- accord and says that it includes Kabul city. -

University of Peshawar Prospectus 2018-19

University of Peshawar Prospectus 2018-19 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION The City of Peshawar 4 Vice Chancellor Message 6 Administration 7 Directorate of Admissions 9 Student Financial Aid Office 10 Academic Programmes 14 Campus Life 15 The Bara Gali Summer Camp 16 Brief Features of Constituent 17 Colleges STUDENTS FACILITIES 19 READING FACILITIES 21 IT FACILITIES 25 HOW TO APPLY? Undergraduate Programme (BS-4 30 Postgraduate Programme (Master-2 39 Years) Years) Higher Studies Programme 52 (M.Phil/MS/Ph.D) FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITY Archaeology 55 Art & Design 57 English & Applied Linguistics 59 History 61 Philosophy 63 Tourism & Hotel Management 65 FACULTY OF ISLAMIC & ORIENTAL STUDIES Arabic 68 Islamiyat 70 Pashto 72 Pashto Academy 74 Persian 76 Seerat Studies 78 Urdu 80 FACULTY OF LIFE & ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Biotechnology & Microbiology 83 Botany 87 Chemical Sciences 89 Disaster Management 92 Environmental Science 97 Geography 100 Geology 102 Pharmacy 104 Plant Biodiversity 106 Urban & Regional Planning 110 Zoology 113 Page 1 University of Peshawar Prospectus 2018-19 FACULTY OF MANAGEMENT & INFORMATION SCIENCES Journalism & Mass 116 Library & Information Sciences 119 Communication Institute of Management Studies 121 Quaid-e-Azam College of Commerce 126 (IMS) FACULTY OF NUMERICAL & PHYSICAL SCIENCES Computer Science 129 Electronics 133 Mathematics 135 Physics 137 Statistics 141 FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Criminology 144 Economics 146 Education & Research (I.E.R) 148 Gender Studies 152 International Relations (IR) 154 Law College 156 Peace -

“Global Terrorism Index: 2015.” Institute for Economics and Peace

MEASURING AND UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF TERRORISM Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP has offices in Sydney, New York and Mexico City. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organizations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org SPECIAL THANKS to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) headquartered at the University of Maryland for their cooperation on this study and for providing the Institute for Economics and Peace with their Global Terrorism Database (GTD) datasets on terrorism. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 ABOUT THE GLOBAL TERRORISM INDEX 6 1 RESULTS 9 Global Terrorism Index map 10 Terrorist incidents map 12 Ten countries most impacted by terrorism 20 Terrorism compared to other forms of violence 30 2 TRENDS 33 Changes in the patterns and characteristics of terrorist activity 34 Terrorist group trends 38 Foreign fighters in Iraq