The Royal Indian Army, Evolution & Organisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 104 – July 2020

THE TIGER Homes for heroes by the sea . THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEICESTERSHIRE & RUTLAND BRANCH OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION ISSUE 104 – JULY 2020 CHAIRMAN’S COLUMN Welcome again, Ladies and Gentlemen, to The Tiger. Whilst the first stage of the easing of the “lockdown” still prevent us from re-uniting at Branch Meetings, there is still a certain amount of good news emanating from the “War Front”. In Ypres, from 1st July, members of the public will be permitted to attend the Last Post Ceremony, although numbers will be limited to 152, with social distancing of 1.5 metres observed. 1st July will also see the re-opening of Talbot House in Poperinghe. Readers will be pleased to learn that the recent fund-raising appeal for the House, featured in this very column in the May edition of The Tiger reached its required target and my thanks go to those of you who donated to this worthy cause. Another piece of news has, as yet, received scant publicity but could prove to be the most important of all. In the aftermath of the recent “attack” on the Cenotaph, during which an attempt was made to set alight our national flag, I was delighted to read in the Press that: a Desecration of War Memorials Bill, carrying a ten year prison sentence, would be brought before the Commons as a matter of urgency. The subsequent discovery that ten years was the maximum sentence rather than the minimum tempered my joy somewhat, but the fact that War Memorials are now finally to be legally placed on a higher plane than other statuary is, at least in my opinion, a major step forward in their protection. -

The Gurkhas', 1857-2009

"Bravest of the Brave": The making and re-making of 'the Gurkhas', 1857-2009 Gavin Rand University of Greenwich Thanks: Matthew, audience… Many of you, I am sure, will be familiar with the image of the ‘martial Gurkha’. The image dates from nineteenth century India, and though the suggestion that the Nepalese are inherently martial appears dubious, images of ‘warlike Gurkhas’ continue to circulate in contemporary discourse. Only last week, Dipprasad Pun, of the Royal Gurkha Rifles, was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross for single-handedly fighting off up to 30 Taliban insurgents. In 2010, reports surfaced that an (unnamed) Gurkha had been reprimanded for using his ‘traditional’ kukri knife to behead a Taliban insurgent, an act which prompted the Daily Mail to exclaim ‘Thank god they’re on our side!) Thus, the bravery and the brutality of the Gurkhas – two staple elements of nineteenth century representations – continue to be replayed. Such images have also been mobilised in other contexts. On 4 November 2008, Chief Superintendent Kevin Hurley, of the Metropolitan Police, told the Commons’ Home Affairs Select Committee, that Gurkhas would make excellent ‘recruits’ to the capital’s police service. Describing the British Army’s Nepalese veterans as loyal, disciplined, hardworking and brave, Hurley reported that the Met’s senior commanders believed that ex-Gurkhas could provide a valuable resource to London’s police. Many Gurkhas, it was noted, were multilingual (in subcontinental languages, useful for policing the capital’s diverse population), fearless (and therefore unlikely to be intimidated by the apparently rising tide of knife and gun crime) and, Hurley noted, the recruiting of these ‘loyal’, ‘brave’ and ‘disciplined’ Nepalese would also provide an excellent (and, one is tempted to add, convenient) means of diversifying the workforce. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

History: India Ww2: Essay Question

HISTORY: INDIA WW2: ESSAY QUESTION Question: how accurate is it to say that the Second World War was the most significant factor driving Indian nationalism in the years 1935 to 1945. (20) One argument for why the Second World War was the most significant factor in driving Indian Nationalism from 1935 to 1945 is because Britain spent vast amounts of money on the Indian army, £1.5 million per year, which made the Indian army feel a boost of self-worth and competence. This would have had a significant effect of Indian nationalism as competence and self- belief are essential in nationalism. Furthermore, Britain paid for most of the costs of Indian troops who fought in North Africa, Italy and elsewhere. This allowed the Indian government to build up a sterling balance of £1,300 million in the reserve Bank of India. This gave Indians freedom of how to spend it which could be spent on new Indian businesses or on infrastructure. This in turn, boosted nationalism as it showed India was becoming less reliant on Britain. However, while India did benefit economically in some aspects from the war, the divisions between Congress and the Muslim League grew. One example of how this occurred could be because the 1937 elections marginalised the Muslim League which made them seem like true nationalists. Once WW2 started these divisions grew as Jinnah returned as a stronger leader wanting better protection of Muslims. As a result, World War Two drove nationalism because of the financial effects on India but increased Muslim nationalism by driving a wedge between the Muslims and Hindus. -

Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Bibliography - Volume II: English and European Languages Shaista Wahab

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Digitized Books 2000 Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Bibliography - Volume II: English and European Languages Shaista Wahab Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wahab, Shaista, "Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Bibliography - Volume II: English and European Languages " (2000). Books in English. Paper 41. http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno/41 This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur Paul Afghanistan Collection Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. v0ILuNJI: 11: ISH AND EUROPEAN LANGUAGE SHATSTA WAHAB Dagefimle Publishing Lincoln, Nebraska Copl;rii$i~ G3009 Univcrsit!; oSNebraska at Omaha. All rights rcscrved. No part of this publication may be reproducc.d. stored in n rm-ieval syslcm, or Iransmitted in any fonn or by any nwans, electronic, niccllanical, photocopied, recorded. or O~~IL'ITV~SC, without 111c prior uritten permission of the au~lior.For in t'ornlation. wi[c Arthur Paul Afgllanistan (:ollcction, University Library. Univer-sih of Ncbrnska at Omaha. Onlaha. NE GS 182-0237 Library of Coligrcss C:ii;~logi~~g-in-Puhlic:i~ionData \\rnImb, Shnisla. Arrllur Paul :\l'ghauis~nnCollcc~ion hbliograpliy i Sllais~n\Vahab. v. : ill. ; 23 cln. Includcs irtdts. "Oascd on 11ic t\f;lin~usra~im:~tc~ials avnilablc in rlic .4r1hur Paul :lfghanis~anCollection a[ thc L'nivcrsi~yLibrary. -

Annual Report 2018-19

GOVENMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 CONTENTS Chapter - 1 1-5 Mandate and Organisational Structure of the Ministry of Home Affairs Chapter - 2 6-33 Internal Security Chapter - 3 34-50 Border Management Chapter - 4 51-55 Centre-State Relations Chapter - 5 56-63 Crime Scenario in the Country Chapter - 6 64-69 Human Rights and National Integration Chapter - 7 70-109 Union Territories Chapter - 8 110-147 POLICE FORCES Chapter - 9 148-169 Other Police Organizations and Institutions Chapter - 10 170-199 Disaster Management Chapter - 11 200-211 International Cooperation Chapter - 12 212-231 Major Initiatives and Schemes Chapter - 13 232-249 Foreigners, Freedom Fighters’ Pension and Rehabilitation Chapter - 14 250-261 Women Safety Chapter - 15 262-274 Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India (RG&CCI) Chapter - 16 275-287 Miscellaneous Issues Annexures 289-337 (I-XXIII) Annual Report 2018-19 Annual Report 2018-19 Chapter - 1 Mandate and Organisational Structure of The Ministry of Home Affairs 1.1 The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) Organisational Chart has also been given discharges multifarious responsibilities, at Annexure-II. the important among them being - internal 1.3 The list of existing Divisions of the security, border management, Centre- Ministry of Home Affairs indicating major State relations, administration of Union areas of their responsibility are as below: Territories, management of Central Armed Police Forces, disaster management, etc. Administration Division Though in terms of Entries 1 and 2 of List II – ‘State List’ – in the Seventh Schedule 1.4 The Administration Division is responsible for handling all administrative to the Constitution of India, ‘public order’ matters and allocation of work among and ‘police’ are the responsibilities of various Divisions of the Ministry. -

Impact of the Sepoy Mutiny on Indian Polity and Society

Impact of the Sepoy Mutiny on Indian Polity and Society claws.in/1420/impact-of-the-sepoy-mutiny-in-indian-polity-and-society-isha-naravane.html #1420 184 August 14, 2015 By Isha Naravane Introduction The events of 1857 loom large in Indian History. Some consider it the first great war of independence, others a mere mutiny and some say it was a revolt against existing conditions. Whatever be the case, the most singular consequence for India’s army was how the British now viewed their armed forces in India. Whether the British ruled it as a trading company or as a nation, the use of force and military might was still necessary to occupy and subjugate the subcontinent. The Revolt of 1857 led to a re-organization of the Indian army and this article highlights some of the socio-economic and cultural impacts of this re-organization. The soldier is also a product of his socio-economic, cultural and political landscape. The recruitment of natives for the British Indian army on a large scale, their training in modern warfare methods, the salary and rewards given to native soldiers all had an impact on the environment where the soldiers came from, on Indian rulers who fielded armies on the battlefield, and on agrarian communities who ultimately shouldered the revenue burden for maintenance of armies. Salient Features Impacting Post-Mutiny Re-Organisation The events of the 1857 uprising all over India are well-documented. This article will discuss those which are pertinent to large scale re-organisation of political and military systems. -

Alison Safadi

alison safadi From Sepoy to Subadar / Khvab-o-Khayal and Douglas Craven Phillott Introduction During the 1970s John Borthwick Gilchrist, convinced of the potential value of the language he called ìHindustani,î1 campaigned hard to raise its status to that of the ìclassicalî languages (Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit) which, until then, had been perceived by the British to be more important than the Indian ìvernaculars.î By 1796 he had already made a valuable contribution to its study with the publication of his dictionary and gram- mar. It was the opening of Fort William College in 1800 by Wellesley, however, that signaled the beginning of the colonial stateís official interest in the language. Understandably, given his pioneering work, a substantial amount has been written on Gilchrist. Much less attention has been paid to the long line of British scholars, missionaries, and military officers who published Hindustani grammars and textbooks over the next 150 years. Although such books continued to be published until 1947, British scholarly interest in Hindustani seemed to have waned by the beginning of World War I. While Gilchrist and earlier authors had aspired to producing literary works, later textbooks were generally written for a much more mundane 1Defining the term ìHindustaniî satisfactorily is problematic but this is not the place to rehearse or debate the often contentious arguments surrounding Urdu/ Hindi/Hindustani. Definitions used by the British grammar and textbook writers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are inconsistent and often contradictory. For the purposes of this paper, therefore, I am using the term in its widest possible sense: to cover the language at all levels, from the literary (Persianized) Bāgh-o- Bahar and (Persian-free) Prem Sagur to the basic ìlanguage of commandî of the twentieth-century military grammars. -

GOD's ACRE in NORTH-WEST INDIA. Ferozpur. THIS Cantonment Is Rich in Memorials of the Glorious Dead. in Fact, the Church" W

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-23-04-04 on 1 October 1914. Downloaded from 415 GOD'S ACRE IN NORTH-WEST INDIA. By COLONEL R. H. FIRTH. (Continued from p. 333.) FERozPUR. THIS cantonment is rich in memorials of the glorious dead. In fact, the church" Was erected to the glory of God in memory of those who fell fighting for their country in this district during the Sutlej Campaign of 1845-1846," and contains many tablets of interest. In the old civil cemetery are graves of the following who especially interest us :- Assistant-Surgeon Robert Beresford Gahan entered the service on June] 7, 1836, and was sent at once to Mauritius. He returned home in ]840, and soon after was posted to the 9th Foot, then in India. Coming out he was unable to join his regiment as it was in Afghanistan, but did general duty in Cawnpur and Meerut, Protected by copyright. ultimately joining it at Sabathu in February, 1843. Towards the end of September, 1845, he was transferred to the 31st Foot,which he joined at Amballa and accompanied them into the field. He was mortally wounded at the battle of Mudki, whilst gallantly doing his professional duties under fire, and died eleven days later in Ferozpur, on December 29, 1845. His name is to be found also on a special monument to the 31st Foot in the cemetery, and on a memorial tablet in St. Andrew's Church. Lieutenant Augustus Satchwell J ohnstone was the son of Surgeon James Johnstone, of the Bengal Medical Service. -

Technical Graduate Course (Tgc-134) (Jan 2022)

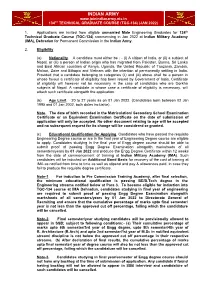

INDIAN ARMY www.joinindianarmy.nic.in 134TH TECHNICAL GRADUATE COURSE (TGC-134) (JAN 2022) 1. Applications are invited from eligible unmarried Male Engineering Graduates for 134th Technical Graduate Course (TGC-134) commencing in Jan 2022 at Indian Military Academy (IMA), Dehradun for Permanent Commission in the Indian Army. 2. Eligibility (a) Nationality. A candidate must either be : - (i) A citizen of India, or (ii) a subject of Nepal, or (iii) a person of Indian origin who has migrated from Pakistan, Burma, Sri Lanka and East African countries of Kenya, Uganda, the United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Malawi, Zaire and Ethopia and Vietnam with the intention of permanently settling in India. Provided that a candidate belonging to categories (ii) and (iii) above shall be a person in whose favour a certificate of eligibility has been issued by Government of India. Certificate of eligibility will however not be necessary in the case of candidates who are Gorkha subjects of Nepal. A candidate in whose case a certificate of eligibility is necessary, will attach such certificate alongwith the application. (b) Age Limit. 20 to 27 years as on 01 Jan 2022. (Candidates born between 02 Jan 1995 and 01 Jan 2002, both dates inclusive). Note. The date of birth recorded in the Matriculation/ Secondary School Examination Certificate or an Equivalent Examination Certificate on the date of submission of application will only be accepted. No other document relating to age will be accepted and no subsequent request for its change will be considered or granted. (c) Educational Qualification for Applying. Candidates who have passed the requisite Engineering Degree course or are in the final year of Engineering Degree course are eligible to apply.