No Selves to Defend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bald Eagle in the Land of Muhammad: American Foreign Policy in the Middle East

A BALD EAGLE IN THE LAND OF MUHAMMAD: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY IN THE MIDDLE EAST by Ari Epstein A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Government Baltimore, Maryland June 2020 © 2020 Ari Epstein All rights reserved Abstract A lack of information regarding American foreign policy in the Middle East can lead to deleterious political decision-making. There are many people both in the civilian world and the world of government that view Middle Eastern related security issues through a sociocultural lens. This thesis portfolio seeks to assess the implications of American foreign policy in the Middle East as opposed to socio-culture. It places emphasis on the theory that American foreign policy contributes to anti-American antagonism. There are a few different methods by which this is measured. First, this thesis will assess American military policy in the Middle East. Specifically, it analyzes the impact of American military policy in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan on Muslim public opinion. This is conducted by looking at numerous sets of data and public polls from different credible organizations, as well as secondary sources. Second, socio-cultural sources are directly assessed in order provide evidence that American foreign policy is the primary driver behind anti-American antagonism. Writings from notorious anti-American figures and scholarly sources on Middle Eastern culture, are considered in order to measure socio-cultural based anti-American antagonism against anti-American antagonism driven by American foreign policy. ii ABSTRACT Third, the diplomatic consequences of the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran Nuclear Agreement are assessed. -

Equity & Social Justice Resource Guide

Metropolitan King County Council Equity & Social Justice Section EQUITY & SOCIAL JUSTICE RESOURCE GUIDE “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” 1 Equity Resources: Compiled using multiple national and local sources, May 2020 [this page left intentionally blank] 2 Equity Resources: Compiled using multiple national and local sources, May 2020 CONTENT I. Terminology THE LAW II. Protected Classes III. Legislation READING: IV. Books V. Blogs and Articles VI. Magazines VII. Reports MEDIA VIII. Films IX. Videos X. Podcast XI. Web Sites LANGUAGE EQUITY TRAININGS (To be added) XII. Online training XIII. Learning & Development FACILITATION (To be added) WELL BEING (To be added) ADDITIONAL READING XIV. Challenging Racism XV. Colorblindness, Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity XVI. Racial Equity Tool Kits XVII. Talking About Pronouns 3 Equity Resources: Compiled using multiple national and local sources, May 2020 TERMINOLOGY The following terminology is commonly used in conversations regarding social justice, diversity, equity and allyship. It is meant to be a starting point for engaging in open and honest conversation by offering a shared language of understanding. Please note, this list is not exhaustive and the meaning of these words may change and evolve based on context. If there is a term that you feel should be included here, please let me know. 1. Ableism: A system of oppression that includes discrimination and social prejudice against people with intellectual, emotional, and physical disabilities, their exclusion, and the valuing of people and groups that do not have disabilities. 2. Accomplice: An ally who directly challenges institutionalized homophobia, transphobia and other forms of oppression, by blocking or impeding oppressive people, policies and structures. -

Molly Crabapple

MOLLY CRABAPPLE Molly Crabapple is an artist and writer in New York. Her 2013 solo exhibition, Shell Game, led to her being called “Occupy's greatest artist” by Rolling Stone, and “an emblem of the way that art could break out of the gilded gallery” by The New Republic. She is the fourth artist in the last decade to draw Guantanamo Bay. Crabapple is a columnist for VICE, and has written for The New York Times, Newsweek, The Paris Review, CNN, The Guardian, The Daily Beast, Jacobin, and Der Spiegel. Harper Collins published her illustrated memoir, Drawing Blood in 2015. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Annotated Muses, Postmasters Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Shell Game: A Crowd-Funded Show about the 2008 Financial Collapse 2008 Deminonde Arena Studios, New York, NY 2007 Peepshow: The Art of Molly Crabapple, Trinity Fine Arts, New York, NY 2006 Tarts and Flowers – A Valentine's Day Show, Jigsaw Gallery Licentious Behavior, Perihelion Arts, Phoenix, AZ 2005 Ink! Babes! Irony!-Molly Crabapple Says Goodbye to Pen and Ink, Jigsaw Gallery GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2015 #WCW (@womencrushwednesday), Postmasters Gallery, New York, NY Respond, Smack Mellon, Brooklyn, NY 2014 Temple of Art Exhibition and Book Launch, La Luz de Jesus Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Portraits in the Twenty First Century, Postmasters Gallery, New York, NY Show Me the Money: The Image of Finance 1700 to the Present, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, UK Message in a Bottle, Cavalier Galleries, Nantucket This is what sculpture looks like, Postmasters Gallery, New York, NY 2013 An Evening in Celebration -

The Death Penalty and the Dawson Five

UCLA National Black Law Journal Title Witness to a Persecution: The Death Penalty and the Dawson Five Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3vx84116 Journal National Black Law Journal, 8(1) ISSN 0896-0194 Author Bedau, Hugo Adam Publication Date 1983 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLES WITNESS TO A PERSECUTION: THE DEATH PENALTY AND THE DAWSON FIVE* Hugo Adam Bedau** The discretionary power . in determining whether a prosecution shall be commenced or maintained may well depend upon matters of policy wholly apart from any question of probable cause. A Fortiori, the deci- sion as to what charge to bring is likewise discretionary.2 I When the definitive history of capital punishment in the United States is written, the full story about capital trials, death sentences, and executions in the State of Georgia deserves to play a prominent role. Preliminary tal- lies of all executions in this country since the seventeenth century place Georgia near the head of the list.3 Since 1930, Georgia has legally put to death 366 persons;4 no other jurisdiction has executed so many in this pe- riod.5 Nowhere else in this nation have so many blacks been executed- 298 6-nor in any other state have blacks been so large a percentage of the total.7 Twenty years ago, Georgia led all other jurisdictions in the nation in the variety of statutory offenses for which the death penalty could be im- posed.8 Among classic miscarriages of justice, Georgia also has made its contribution with the death in 1915 of Leo Frank, lynched near Marietta * The prosecution subsequently dropped all charges against the five defendants; therefore, there is no published report of the case. -

•Š the Joan Little Case and Anti-Rape Activism

Catherine Jacquet University of Illinois at Chicago UCLA, Thinking Gender conference 2010 [email protected] Catherine Jacquet is a PhD candidate in history at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her dissertation focuses on the politics of rape, 1960-1980. This is a work in progress. Please do not quote without permission of the author. “Where are all the feminists?” 1 The Joan Little case and anti-rape activism during the 1970s A steady rain, sometimes pouring, fell over Raleigh, North Carolina on Monday, July 14, 1975. The bad weather didn’t stop the 300 to 500 protestors, some of whom had travelled from Chicago, Richmond, Norfolk, and Baltimore, as they marched from the Women’s Correctional Center, through the streets of downtown Raleigh, and finally gathered on the steps of the Wake County Courthouse. Flanked by police in riot gear, the demonstrators carried banners that read: “Stop Slave Labor in NC prisons,” “Black Panther Party demands freedom for Sister Joanne Little”, “Drop the charges,” and “Women have a right to self defense.” 2 The demonstrators had gathered for the first day of the Joan Little trial, a story that had exploded to nationwide and international attention over the previous 10 months. 3 On August 27, 1974, 20-year-old black inmate Joan Little escaped from Beauford County Jail in the small town of Washington, North Carolina, after killing Clarence Alligood, a white officer at the facility. Another officer found Alligood dead in Little’s cell, naked from the waist down with ejaculate on his thigh. Little was gone. When she 1 Interview with Marjory Nelson, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. -

Selecting a Jury in Political Trials

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 27 Issue 3 Article 3 1977 Selecting a Jury in Political Trials Jon Van Dyke Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jon Van Dyke, Selecting a Jury in Political Trials, 27 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 609 (1977) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol27/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Selecting a Jury in Political Trials* Jon Van Dyke** Because juries exercise the controversial power of tailoring static law to the exigencies of a particular case, it is imperative that the jury constitute a cross- section of the community. Impaneling a representativejury is even more difficult, and more critical, in a highly publicized politicul trial. Professor Van Dyke examines the justifications for the defendant's ue of social science techniques to scrutinize prospectivejurors, andfinds that such practices sometimes lead to public doubt about the impartialityof the jury's verdict. He concludes that although some defense attorneys may be obliged to survey the attitudes of potentialjurors to over- come biases in the jury selection process, the interests of justice would be better served ifthe lists used to impanel jurors were more complete, iffewer excuses and challenges were allowed, and if (as a result) the resulting jury more accurately reflected the diversity of the community. -

Does Occupy Signal the Death of Contemporary Art? by Paul Mason Economics Editor, Newsnight

Does Occupy signal the death of contemporary art? By Paul Mason Economics editor, Newsnight There has been so much art centred around the Occupy protests that it is beginning to feel like a new artistic movement. What defines it, and could it supplant the world of the galleries? We get in the van and speed along to Bed-Stuy. It is the New York equivalent of London's Shoreditch or Berlin's Prenzlauer Berg, a hipster sub-metropolis, but with cuter beards. I am with The Illuminators - a group of performance artists whose art is to shine revolutionary logos onto buildings in support of the Occupy Wall Street protest, including one that has become iconic - the 99% logo, known to protesters as "the bat signal". http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-17872666 In the van is not just a projector and a laptop, but also posters, a mobile library, and a whole vat of hot chocolate. The woman controlling the projector is a union organiser. The man vee-jaying the video is - well, a vee-jay (video jockey) in real life, but for corporates, fashion shows and the like. Molly Crabapple's Vampire Squid was appropriated by Occupy protesters across the US And Mark Read, the driver and instigator, is a college lecturer in media studies. "The bat signal is really simple. It's big and it reads as a bat signal - it's culturally legible," he says. It's a call to arms and a call for aid, but instead of a super-hero millionaire psychopath, like Bruce Wayne, it's ourselves - it's the 99% coming to save itself. -

7:30PM BHB Brickhouse Brewery and Restaurant @67 W

TONIGHT Saturday Feb. 9 from 6:00 PM – 7:30PM BHB Brickhouse Brewery and Restaurant @67 W. Main St., Patchogue Patchogue Arts Council presents To the Light • Ayako Bando curated by John Cino @ Shand’s Loft, Brickhouse Brewery and Restaurant February 2 – 24, 2019 Ayako Bando was born in Tokushima, Japan where she recalls being “surrounded by the beauty of nature with its mountains, rivers, trees and flowers”. Since 2014 she has worked on the “Towanohikari” series which translates as “Eternal Light”, a light that illuminates our hearts and brings purity. Inspired by her youth and the works of Wassily Kandinsky, she sees the light emanating from the spirit intertwining “people and nature with the same common forces of life, where we are all connected … born pure and innocent into this world”. Ayako Bando has studied art in Osaka, Tokyo, London and New York. She has earned numerous awards in Japan and has exhibited in Japan, the US, Germany and Italy. TONIGHT Saturday Feb. 9 from 6:00 PM – 9:00PM Muñeca Arthouse @12 South Ocean Ave Muñeca Arthouse welcomes their first official solo exhibition will be: "The Art of Protest: The Political Watercolours of Molly Crabapple." curated by J. Valentin & B.Giacummo It will run at Muñeca Arthouse, February and March. Opening reception Saturday February 9th 6-9pm and book signing with Molly Crabapple in March. This exhibition features Original Occupy Wall Street posters as well as other political posters created by Molly Crabapple. A limited number of archival collectable prints available. A series of animations including a piece created with the Equal Justice Initiative created by the artists will also be screened in the gallery during the entire exhibition. -

Works for Social Change Pop Culture

WORKS FOR SOCIAL CHANGE POP CULTURE: POP CULTURE: At AndACTION, we know that stories have power. “The Invisible War” is a harrowing documentary about the tens of thousands of sexual assaults A POWERFUL WAY TO DRIVE SOCIAL CHANGE. TO WAY A POWERFUL that take place every year within the U.S. military. Within days of seeing the film in 2012, former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta announced a significant change in the way reported rapes are investigated in the military. What’s more, he told one of the film’s executive producers that the film was responsible, in part, for his decision. From big movie screens to small televisions to tiny hand- held devices, stories have the unique ability to move viewers to think about important issues – and to Photo credit: Cinedigm take action on them. Pop culture stories are some of the most moving, compelling stories told. From “The Help” exposing the plight of domestic workers to “Modern Family” evolving our understanding of what family is to “Hidden Figures” reshaping our view of women’s contributions to history, everyday movies and TV shows offer people working on important issues a way to emotionally connect people to their cause and be motivated to do more. Pop culture is uniquely suited to meet strategic communication aims of nonprofits from reducing stigma to changing social norms to giving people a sense of a lived experience that changes hearts and minds. However, organizations often lack the staff or internal resources needed to execute the kind of rapid-response campaign necessary to take advantage of current pop culture storylines. -

Zak Smith Born, July 16, 1976 in Syracuse, NY Lives and Works in Los Angeles, California

Zak Smith Born, July 16, 1976 in Syracuse, NY Lives and works in Los Angeles, California EDUCATION: 1999-2001 Yale University, New Haven, CT, MFA 1999 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME 1994-1998 Cooper Union, New York, NY, BFA SOLO EXHIBITIONS: 2018 Fredericks & Freiser, New York, NY, 1001 Nights 2016 Fredericks & Freiser, New York, NY 2015 Richard Heller Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2013 Fredericks & Freiser, New York, NY, Maximum Everything Always 2010 Fredericks & Freiser, New York, NY, A Show About Nothing 2008 Fredericks & Freiser, New York, NY Midnight in the Empire 2007 Fred, London, UK Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago, IL Half the Artist's Proceeds from This Show Will Go to Benefit the Victims of God and Capitalism 2005 Fredericks & Freiser, New York, NY, Exquisite as Fuck 2004 Franklin Art Works, Minneapolis, MN, Hope You Like It 2003 Fredericks Freiser Gallery, New York, NY, Paintings That Look Good and Were Hard to Make 2002 Fredericks Freiser Gallery, New York, NY, 20 Eyes in My Head Yale Norfolk Summer Program, Norfolk, CT SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS: 2019 Fredericks & Freiser, Damn! The Defiant, New York, NY 2018 COOP Gallery, Golden Underbelly, Nashville, TN 2017 Fredericks & Freiser, UNTITLED Art Fair, Miami Beach, FL Chimento Contemporary, The Dick Pic Show, Los Angeles, CA Fabien Castanier Gallery, Culver City, CA 2016 C. Nichols Project, Kappa, Mar Vista, CA 2015 Fredericks & Freiser, UNTITLED Art Fair, Miami Beach, FL Steven Wolf Fine Arts, It’s My Job to be a Girl, San Francisco, CA (two-person exhibition with William T. Vollmann) 2014 Fredericks & Freiser, UNTITLED Art Fair, Miami Beach, FL Fredericks & Freiser, The Armory Show, New York, NY 2013 Fredericks & Freiser, Miami Project, Miami, FL Saatchi Gallery, London, England, Paper Fredericks & Freiser, Expo Chicago, IL 2012 Fredericks & Freiser, Expo Chicago, IL 2010 MoCCA (Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art), New York, NY. -

The Case of Aileen Carol Wuornos

St. John's Law Review Volume 66 Number 4 Volume 66, Fall-Winter 1993, Number Article 1 4 A Woman's Right to Self-Defense: The Case of Aileen Carol Wuornos Phyllis Chesler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST. JOHN'S LAW REVIEW VOLUME 66 FALL-WINTER 1993 NUMBER 4 WOMEN IN THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A WOMAN'S RIGHT TO SELF-DEFENSE: THE CASE OF AILEEN CAROL WUORNOS PHYLLIS CHESLER* For the first time in U.S. history, a woman stands accused of being a serial killer: of having killed six adult male motorists, one by one, in just over a year, after accompanying them to wooded areas off Highway 75 in Florida, a state well-known for its sun, surf, and serial killers. I first heard about Aileen (Lee) Carol Wuornos in December of * B.A. Bard College, 1962; M.A. The New School for Social Research, 1967; Ph.D. The New School for Social Research, 1969. Phyllis Chesler is the author of six books including Women and Madness, Mothers on Trial: The Battle for Children and Custody, and Sacred Bond: The Legacy of Baby M. She is a Professor of Psychology at the College of Staten Island, City University of New York, an expert witness on psychology, and a co-founder of The National Women's Health Network and The Association for Women in Psychology. -

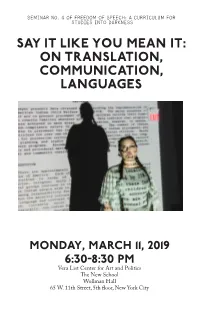

Say It Like You Mean It: on Translation, Communication, Languages

SEMINAR NO. 4 OF FREEDOM OF SPEECH: A CURRICULUM FOR STUDIES INTO DARKNESS SAY IT LIKE YOU MEAN IT: ON TRANSLATION, COMMUNICATION, LANGUAGES MONDAY, MARCH 11, 2019 6:30-8:30 PM Vera List Center for Art and Politics The New School Wollman Hall 65 W. 11th Street, 5th floor, New York City VERA LIST CENTER FOR ART AND POLITICS The Vera List Center for Art and Politics is a research center and a public forum for art, culture, and politics. It was established at The New School in 1992—a time of rousing debates about freedom of speech, identity politics, and society’s investment in the arts. A pioneer in the field, the center is a nonprofit that serves a critical mission: to foster a vibrant and diverse community of artists, scholars, and policy makers who take creative, intellectual, and political risks to bring about positive change. We champion the arts as expressions of the political moments from which they emerge, and consider the intersection between art and politics the space where new forms of civic engagement must be developed. We are the only university-based institution committed exclusively to leading public research on this intersection. Through public programs and classes, prizes and fellowships, publications and exhibitions that probe some of the pressing issues of our time, we curate and support new roles for the arts and artists in advancing social justice. www.veralistcenter.org FREEDOM OF SPEECH: A CURRICULUM FOR STUDIES INTO DARKNESS Say It Like You Mean It: On Translation, Communication, Languages is the fourth seminar in a year-long examination of Freedom of Speech.