Knives and the Second Amendment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Politics of Gun Control Nicholas J

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 2 Article 2 2006 A Second Amendment Moment: The Constitutional Politics of Gun Control Nicholas J. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Nicholas J. Johnson, A Second Amendment Moment: The Constitutional Politics of Gun Control, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2005). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. A Second Amendment Moment THE CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS OF GUN CONTROL Nicholas J. Johnson† I. INTRODUCTION A. Constitutional Politics Bruce Ackerman’s claim that America’s endorsement of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal policies actually changed the United States Constitution to affirm an activist regulatory state, advances the idea that higher lawmaking on the same order as Article Five amendment can be attained through and discerned by attention to our “constitutional politics.”1 Ackerman’s “Dualist” model requires that we distinguish between two types of politics.2 In normal politics, organized interest groups try to influence democratically elected representatives while regular citizens get on with life.3 In constitutional politics, the mass of citizens are energized to engage and debate matters of fundamental principle.4 Our history is dominated by normal politics. But our tradition places a higher value on mobilized efforts to gain the consent of † Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law, J.D. Harvard Law School, 1984, B.S.B.A. -

The Gendered Feast: Experiencing a Georgian Supra Laura Joy Linderman

The Gendered Feast: Experiencing a Georgian Supra Laura Joy Linderman Abstract: The supra is a traditionalized feast in post-Soviet Georgia characterized by abundant food and ritualized drinking. It is extremely common in social life, especially in rural Georgia. Secular rituals, social occasions, national and religious holidays and life cycle transitions are accompanied by the ubiquitous supra. The supra has been examined by anthropologists as a site for macro level analyses that put forward structural or cultural theories for the underlying meaning of this ritual-for-all-occasions. Women’s experiences of and roles in the supra have often been overlooked or misrepresented in these studies. In this thesis I investigate women’s varied roles at a supra and problematize the idea that the supra demonstrates a model of society, with a paragon of masculinity at the center. I question the static image of an idealized supra that is only capable of reproducing a particular cultural model and argue that the supra is flexibly employed with a great deal of social life being oriented around preparing and participating in supras. Women’s experiences of the supra (like men’s) is different depending on the type of supra, the other participants involved, the age of the woman, her class and her particular geographical location. Keywords: post-Soviet, Georgia (Republic), cultural anthropology, feast, banquet, ritual, gender Introduction The supra was the worst and best experience I had in Georgia. Georgians have supras about 3 times a week to celebrate different things, whether it be a wedding, holiday, etc. In this case, the supra was for us. -

Vielfalt: Ausgesuchte Sport-, Sammler- Und Einsatzmesser Weltweit Renommierter Messer-Marken

Vielfalt: Ausgesuchte Sport-, Sammler- und Einsatzmesser weltweit renommierter Messer-Marken. [Seite 114-225] 114 Weitere Produkte, Informationen und zusätzliche Abbildungen im Internet unter www.boker.de INTERNATIONAL SELECTION | USA | CRKT DAS GESAMTE 1 CRKT-SO-SORTIMENT V.A.S.P. Plain. € 59,95 FINDEN SIE UNTER www.boker.de.de 2 V.A.S.P. Veff Serration. € 59,95 3 Buy Tighe 20th Anniversary. € 750,- 4 Shenanigan Realtree Xtra Camo. € 69,95 5 Shenanigan Realtree Xtra Green. € 69,95 V.A.S.P. (VERIFY ADvaNCE SECURE 2 V.A.S.P. VEFF SERRATION – Mit Das Jubiläumsmesser ist streng limi- In folgenden Ausführungen erhältlich: PROCEED) – Ein Messer zum Veff Serration für den groben Einsatz. tiert auf 500 Exemplare weltweit. Zupacken aus der Feder von Steve Best.-Nr. 01CR7481 € 59,95 Ges. 31,3 cm. Kl. 8,9 cm. 4 SHENANIGAN REALTREE XTRA Jernigan. Durch den sehr diskreten Stärke 3 mm. Gew. 179 g. CaMO Flipper und das IKBS-Kugellager lässt 3 BUY TIGHE 20TH ANNIVERsaRY Best.-Nr. 01CR5260 € 750,- Best.-Nr. 01CR480CXP € 69,95 sich die Klinge komfortabel und flüs- Brian Tighe, bekannt für seine außer- sig öffnen und arretiert per Linerlock. gewöhnlichen Entwürfe, hat sich SHENANIGAN CAMO – Die äußerst 5 SHENANIGAN REALTREE XTRA Die zuverlässige und robuste anlässlich des 20sten Jubiläums von beliebte Shenanigan-Serie von Ken GREEN Konstruktion garantiert einen sicheren CRKT etwas ganz extravagantes Onion geht mit diesen Modellen in Best.-Nr. 01CR481CXP € 69,95 und verlässlichen Einsatz im Beruf, einfallen lassen. Ein Griff, zwei gegen- die nächste Runde. Für den Jäger beim Sport oder in der Freizeit. -

Legal Notice

Legal Notice Date: October 19, 2017 Subject: An ordinance of the City of Littleton, amending Chapter 4 of Title 6 of the Littleton Municipal Code Passed/Failed: Passed on second reading CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO ORDINANCE NO. 28 Series, 2017 INTRODUCED BY COUNCILMEMBERS: HOPPING & BRINKMAN DocuSign Envelope ID: 6FA46DDD-1B71-4B8F-B674-70BA44F15350 1 CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO 2 3 ORDINANCE NO. 28 4 5 Series, 2017 6 7 INTRODUCED BY COUNCILMEMBERS: HOPPING & BRINKMAN 8 9 AN ORDINANCE OF THE CITY OF LITTLETON, 10 COLORADO, AMENDING CHAPTER 4 OF TITLE 6 OF 11 THE LITTLETON MUNICIPAL CODE 12 13 WHEREAS, Senate Bill 17-008 amended C.R.S. §18-12-101 to remove the 14 definitions of gravity knife and switchblade knife; 15 16 WHEREAS, Senate Bill 17-088 amended C.R.S. §18-12-102 to remove any 17 references to gravity knives and switchblade knives; and 18 19 WHEREAS, the city wishes to update city code in compliance with these 20 amendments to state statute. 21 22 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF 23 THE CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO, THAT: 24 25 Section 1: Section 151 of Chapter 4 of Title 6 is hereby revised as follows: 26 27 6-4-151: DEFINITIONS: 28 29 ADULT: Any person eighteen (18) years of age or older. 30 31 BALLISTIC KNIFE: Any knife that has a blade which is forcefully projected from the handle by 32 means of a spring loaded device or explosive charge. 33 34 BLACKJACK: Any billy, sand club, sandbag or other hand operated striking weapon consisting, 35 at the striking end, of an encased piece of lead or other heavy substance and, at the handle end, a 36 strap or springy shaft which increases the force of impact. -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

Food, Globalism and Theory: Marxian and Institutionalist Insights Into the Global Food System Charles R.P

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 10-1-2011 Food, Globalism and Theory: Marxian and Institutionalist Insights into the Global Food System Charles R.P. Pouncy Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Charles R.P. Pouncy, Food, Globalism and Theory: Marxian and Institutionalist Insights into the Global Food System, 43 U. Miami Inter- Am. L. Rev. 89 (2011) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol43/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 89 Food, Globalism and Theory: Marxian and Institutionalist Insights into the Global Food System Charles R. P. Pouncy* INTRODUCTION In June 2009, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reported that world hunger was expected to reach unprecedented highs as more than 100 million additional people were forced into the ranks of the hungry, resulting in 1.02 billion people being undernourished each day.' Although the numbers have moderated somewhat since that time, the first decade of the 21st century has witnessed a steady increase in the number of hungry people. 2 Importantly, the increase in hunger is not a prob- lem of supply. Food production figures are generally strong, and it is largely conceded that there is enough food to feed everyone on the planet.3 Instead, the problem results from the ideologies asso- ciated with food distribution. -

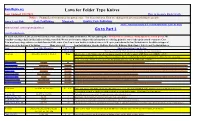

Laws for Folder Type Knives Go to Part 1

KnifeRights.org Laws for Folder Type Knives Last Updated 1/12/2021 How to measure blade length. Notice: Finding Local Ordinances has gotten easier. Try these four sites. They are adding local government listing frequently. Amer. Legal Pub. Code Publlishing Municode Quality Code Publishing AKTI American Knife & Tool Institute Knife Laws by State Admins E-Mail: [email protected] Go to Part 1 https://handgunlaw.us In many states Knife Laws are not well defined. Some states say very little about knives. We have put together information on carrying a folding type knife in your pocket. We consider carrying a knife in this fashion as being concealed. We are not attorneys and post this information as a starting point for you to take up the search even more. Case Law may have a huge influence on knife laws in all the states. Case Law is even harder to find references to. It up to you to know the law. Definitions for the different types of knives are at the bottom of the listing. Many states still ban Switchblades, Gravity, Ballistic, Butterfly, Balisong, Dirk, Gimlet, Stiletto and Toothpick Knives. State Law Title/Chapt/Sec Legal Yes/No Short description from the law. Folder/Length Wording edited to fit. Click on state or city name for more information Montana 45-8-316, 45-8-317, 45-8-3 None Effective Oct. 1, 2017 Knife concealed no longer considered a deadly weapon per MT Statue as per HB251 (2017) Local governments may not enact or enforce an ordinance, rule, or regulation that restricts or prohibits the ownership, use, possession or sale of any type of knife that is not specifically prohibited by state law. -

Congressional Record-Senate. Decemb~R 8

196 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. DECEMB~R 8, gress hold no session for legislative purposes on Sunday-to the Com Mr. II.A.LE presented a petition of the Master Builders' Exchange mittee on the Judiciary. of Philadelphia, Pa., praying for a more careful investigation by the By Mr. O'NEILL, of Pennsylvania: Resolutions of the Tobacco Census Office of the electrical industries; which was referred :to the Trade Association of Philadelphia, requesting Congress to provide by Committee on the Census. legislation for the payment of a rebate of 2 cents per pound on the Ile also presenteda resolution adopted by the ChamberofCommerce stock of tax-paid tobacco and snuff on hand on the 1st of January, of New Haven, Conn., favoring the petition of the National Electric 1891-to the Committee on Ways and Means. Light Association, praying for a more careful investigation by the Cen By Mr. PETERS: Petition of Wichita wholesale grocers and numer sus Office of the electrical industries; which wus referred to the Com ous citizens of Kansa8, for rebate amendment to tariff bill-to the mittee on the Census. Committee on Ways and Means. l\Ir. GORMAN. I present a great number of memorials signed by By Mr. THOMAS: Petition ofW. Grams,W. J. Keller.and 9others, very many residents of the United States, remonstrating against the of La Crosse, ·wis., and B. T. Ilacon and 7 others, of the State of Minne passage of the Federal election bill now pending, or any other bill of sota, praying for the passage of an act or rebate amendment to the like purport, wb~ch the memoriali5ts think would tend to destroy the tariff law approved October 1, 1890, allowing certain drawbacks or re purity of elections, and would unnecessarily impose heavy burdens bates upon unbroken packages of smoking and manufactured tobacco on the taxpayers, and be revolutionizing the constitutional practices and snuffs-to the Committee on Ways and Means. -

From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University

Civility at Sea: From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University n 1749 the articles of war that regulated life aboard His Britannic Majesty’s I vessels stipulated: If any Person in or belonging to the Fleet shall make or endeavor to make any mutinous Assembly upon any Pretense whatsoever, every Person offending herein, and being convicted thereof by the Sentence of the Court Martial, shall suffer Death: and if any Person in or belong- ing to the Fleet shall utter any Words of Sedition or Mutiny, he shall suffer Death, or such other Punishment as a Court Martial shall deem him to deserve. [Moreover] if any Person in or belonging to the Fleet shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous Words spoken by any, to the Prejudice of His Majesty or Government, or any Words, Practice or Design tending to the Hindrance of the Service, and shall not forthwith reveal the same to the Commanding Officer; or being present at any Mutiny or Sedition, shall not use his utmost Endeavors to suppress the same, he shall be punished as a Court Martial shall think he deserves.1 These stern edicts inform a common image of the cowed life of ordinary sailors aboard vessels of the Royal Navy during its golden age, an image affirmed by the testimony of Jack Nastyface (also known as William Robinson, 1787–ca. 1836), for whom the sailor’s lot involved enforced silence under threat of barbarous and tyrannical punishment.2 In the soundscape of maritime life 1 Articles 19 and 20 of An Act for Amending, Explaining and Reducing into One Act of Parliament, the Laws Relating to the Government of His Majesty’s Ships, Vessels and Forces by Sea (also known as the 1749 Naval Act or the Articles of War), 22 Geo. -

March 2008 Camillus (Kah-Mill-Us) the Way They Were by Hank Hansen

Camillus Knives Samurai Tales Are We There Yet? Shipping Your Knives Miss You Grinding Competition Ourinternational membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” March 2008 Camillus (Kah-mill-us) The Way They Were by Hank Hansen In recent months we have read about the last breaths of a fine old cutlery tangs. The elephant toenail pattern pictured has the early 3-line stamp on both company and its sad ending; but before this, Camillus was a great and exciting tangs along with the sword brand etch. Also the word CAMILLUS, in double firm that produced wonderful knives. When you look at some of the knives that outlined bold letters, was sometimes etched on the face of the master blade along they made in the past, some of them will certainly warm your hearts and make with the early 3-line tang marks. you wonder, why, why did I not appreciate the quality and beauty of these knives made in NewYorkState a long time ago. The different tang stamps used by Camillus, and the time period they were used, are wonderfully illustrated by John Goins in his Goins’Encyclopedia of Cutlery The Camillus Cutlery Co. was so named in 1902. It had its start some eight years Markings, available from Knife World. Other house brands that were used earlier when Charles E. Sherwood founded it on July 14, 1894, as the Sherwood include Camco, Catskill, Clover, Corning, Cornwall, Fairmount, Farragut, Cutlery Co., in Camillus, New York. The skilled workers at the plant had come Federal, High Carbon Steel, Mumbley Peg, Stainless Cutlery Co, Streamline, from England. -

PIRATES Ssfix.Qxd

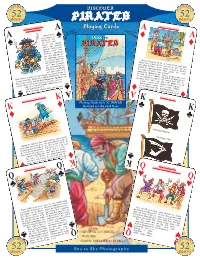

E IFF RE D N 52 T DISCOVERDISCOVER FAMOUS PIRATES B P LAC P A KBEARD A IIRRAATT Edward Teach, E E ♠ E F R better known as Top Quality PlayingPlaying CardsCards IF E ♠ SS N Plastic Coated D Blackbeard, was T one of the most feared and famous 52 pirates that operated Superior Print along the Caribbean and A Quality PIR Atlantic coasts from ATE TR 1717-18. Blackbeard ♦ EAS was most infamous for U RE his frightening appear- ance. He was huge man with wild bloodshot eyes, and a mass of tangled A hair and beard that was twisted into dreadlocks, black ribbons. In battle, he made himself andeven thenmore boundfearsome with by ♦ wearing smoldering cannon fuses stuffed under his hat, creating black smoke wafting about his head. During raids, Blackbeard car- ried his cutlass between his teeth as he scaled the side of a The lure of treasure was the driving force behind all the ship. He was hunted down by a British Navy crew risks taken by Pirates. It was ♠ at Ocracoke Inlet in 1718. possible to acquire more booty Blackbeard fought a furious battle, and was slain ♠ in a single raid than a man or jewelry. It was small, light, only after receiving over 20 cutlass wounds, and could earn in a lifetime of regu- and easy to carry and was A five pistol shots. lar work. In 1693, Thomas widely accepted as currency. A Tew once plundered a ship in Other spoils were more WALKING THE PLANK the Indian Ocean where each practical: tobacco, weapons, food, alco- member received 3000 hol, and the all important doc- K K ♦ English pounds, equal to tor’s medical chest. -

The Cutting Edge of Knives

THE CUTTING EDGE OF KNIVES A Chef’s Guide to Finding the Perfect Kitchen Knife spine handle tip blade bolster rivets c utting edge heel of a knife handle tip butt blade tang FORGED vs STAMPED FORGED KNIVES are heated and pounded using a single piece of metal. Because STAMPED KNIVES are stamped out of metal; much like you’d imagine a license plate would be stamped theyANATOMY are typically crafted by an expert, they are typically more expensive, but are of higher quality. out of a sheet of metal. These types of knives are typically less expensive and the blade is thinner and lighter. KNIFEedges Plain/Straight Edge Granton/Hollow Serrated Most knives come with a plain The grooves in a granton This knife edge is perfect for cutting edge. This edge helps the knife edge knife help keep food through bread crust, cooked meats, cut cleanly through foods. from sticking to the blade. tomatoes & other soft foods. STRAIGHT GRANTON SERRATED Types of knives PARING KNIFE 9 Pairing 9 Pairing 9 Asian 9 Asian 9 Steak 9 Cheese STEAK KNIFE 9 Utility 9 Asian 9 Santoku Knife 9 Butcher 9 Utility 9 Carving Knife 9 Fillet 9 Cheese 9 Cleaver 9 Bread BUTCHER KNIFE 9 Chef’s Knife 9 Boning Knife 9 Santoku Knife 9 Carving Knife UTILITY KNIFE MEAT CHEESE KNIFE (INCLUDING FISH & POULTRY » PAIRING » CLEAVER » ASIAN » CHEF’S KNIFE FILLET KNIFE » UTILITY » BONING KNIFE » BUTCHER » SANTOKU KNIFE » FILLET CLEAVER PRODUCE CHEF’S KNIFE » PAIRING » CHEF’S KNIFE » ASIAN » SANTOKU KNIFE » UTILITY » CARVING KNIFE BONING KNIFE » CLEAVER CHEESE SANTOKU KNIFE » PAIRING » CHEESE » ASIAN » CHEF’S KNIFE UTILITY » BREAD KNIFE COOKED MEAT CARVING KNIFE » STEAK » FILLET » ASIAN » CARVING ASIAN KNIVES offer a type of metal and processing that BREAD is unmatched by other types of knives typically produced from » ASIAN » BREAD the European style of production.