A Case Study of Gravity Knife Legislation in New York City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Notice

Legal Notice Date: October 19, 2017 Subject: An ordinance of the City of Littleton, amending Chapter 4 of Title 6 of the Littleton Municipal Code Passed/Failed: Passed on second reading CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO ORDINANCE NO. 28 Series, 2017 INTRODUCED BY COUNCILMEMBERS: HOPPING & BRINKMAN DocuSign Envelope ID: 6FA46DDD-1B71-4B8F-B674-70BA44F15350 1 CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO 2 3 ORDINANCE NO. 28 4 5 Series, 2017 6 7 INTRODUCED BY COUNCILMEMBERS: HOPPING & BRINKMAN 8 9 AN ORDINANCE OF THE CITY OF LITTLETON, 10 COLORADO, AMENDING CHAPTER 4 OF TITLE 6 OF 11 THE LITTLETON MUNICIPAL CODE 12 13 WHEREAS, Senate Bill 17-008 amended C.R.S. §18-12-101 to remove the 14 definitions of gravity knife and switchblade knife; 15 16 WHEREAS, Senate Bill 17-088 amended C.R.S. §18-12-102 to remove any 17 references to gravity knives and switchblade knives; and 18 19 WHEREAS, the city wishes to update city code in compliance with these 20 amendments to state statute. 21 22 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF 23 THE CITY OF LITTLETON, COLORADO, THAT: 24 25 Section 1: Section 151 of Chapter 4 of Title 6 is hereby revised as follows: 26 27 6-4-151: DEFINITIONS: 28 29 ADULT: Any person eighteen (18) years of age or older. 30 31 BALLISTIC KNIFE: Any knife that has a blade which is forcefully projected from the handle by 32 means of a spring loaded device or explosive charge. 33 34 BLACKJACK: Any billy, sand club, sandbag or other hand operated striking weapon consisting, 35 at the striking end, of an encased piece of lead or other heavy substance and, at the handle end, a 36 strap or springy shaft which increases the force of impact. -

Proposed Michigan Ban on “Multi

www.akti.org Official Publication of the American Knife and Tool Institute, Inc. Vol. 6 Issue 3 Fall 2004 Proposed Michigan Ban on “Multi-bladed Devices” On Hold Michigan bills introduced in Spring edged, multibladed device with blades Several groups and organizations, 2004 proposed to modify language in capable of being locked into place.” In including the NRA, opposed the bill on many sections of the Michigan Penal another section of the bill, this same lan- multiple grounds. AKTI alerted three ma- Code. Among other things, the bills guage was restated in a way that made it jor Michigan knife clubs, as well as key (House Bill No. 5797; Senate Bill No. even more ambiguous and, ultimately in knife suppliers in the state, asking them 1296) would have outlawed any “sharp- AKTI’s view, unenforceable. to contact key sponsors, committee heads and their local representatives. We also asked other affected knife owners, who might visit the state and be subject AKTI Responds to Wisconsin “Rumor” to prosecution, to register their concerns. AKTI was contacted in late August 2004 by a Texas manufacturer who was being AKTI provided model letters for threatened with his knives being pulled from a Midwest farm and outdoor retail chain. their use, as we do in all such instances. AKTI does not render legal opinions for either members or non-members (although we We also directed a letter to the sponsor- are developing a list of attorneys willing to consult with counsel hired by a defen- ing lawmakers and key committee heads. dant). In this case, we forwarded a letter to the manufacturer which may prove in- The text of the following letter expresses structive to others in similar situations. -

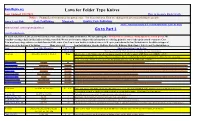

Laws for Folder Type Knives Go to Part 1

KnifeRights.org Laws for Folder Type Knives Last Updated 1/12/2021 How to measure blade length. Notice: Finding Local Ordinances has gotten easier. Try these four sites. They are adding local government listing frequently. Amer. Legal Pub. Code Publlishing Municode Quality Code Publishing AKTI American Knife & Tool Institute Knife Laws by State Admins E-Mail: [email protected] Go to Part 1 https://handgunlaw.us In many states Knife Laws are not well defined. Some states say very little about knives. We have put together information on carrying a folding type knife in your pocket. We consider carrying a knife in this fashion as being concealed. We are not attorneys and post this information as a starting point for you to take up the search even more. Case Law may have a huge influence on knife laws in all the states. Case Law is even harder to find references to. It up to you to know the law. Definitions for the different types of knives are at the bottom of the listing. Many states still ban Switchblades, Gravity, Ballistic, Butterfly, Balisong, Dirk, Gimlet, Stiletto and Toothpick Knives. State Law Title/Chapt/Sec Legal Yes/No Short description from the law. Folder/Length Wording edited to fit. Click on state or city name for more information Montana 45-8-316, 45-8-317, 45-8-3 None Effective Oct. 1, 2017 Knife concealed no longer considered a deadly weapon per MT Statue as per HB251 (2017) Local governments may not enact or enforce an ordinance, rule, or regulation that restricts or prohibits the ownership, use, possession or sale of any type of knife that is not specifically prohibited by state law. -

A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers Second Edition December, 2015

A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers Second Edition December, 2015 How to tell if a knife is “illegal.” An analysis of current California knife laws. By: This article is available online at: http://bit.ly/knifeguide I. Introduction California has a variety of criminal laws designed to restrict the possession of knives. This guide has two goals: • Explain the current California knife laws using plain language. • Help individuals identify whether a knife is or is not “illegal.” This information is presented as a brief synopsis of the law and not as legal advice. Use of the guide does not create a lawyer/client relationship. Laws are interpreted differently by enforcement officers, prosecuting attorneys, and judges. Dmitry Stadlin suggests that you consult legal counsel for guidance. Page 1 A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers II. Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................... 1 II. Table of Contents ............................................................................ 2 III. Table of Authorities ....................................................................... 4 IV. About the Author .......................................................................... 5 A. Qualifications to Write On This Subject ............................................ 5 B. Contact Information ...................................................................... 7 V. About the Second Edition ................................................................. 8 A. Impact -

Vol 10 Issue 3.Qxd

www.akti.org Official Publicationnews of the American Knife && Tool Institute,update Inc. Volume 10 Issue 3 2008 AKTI's South Carolina Pro-Knife Bill Becomes Law By David D. Kowalski, AKTI Communications Coordinator "We have a law," AKTI lobbyist the 34 Senators present (of 46 total) start- amended to read: … 'weapon' means Palmer Freeman announced late in the ed the process. They voted 33-1 to over- firearm (rifle, shotgun, pistol, or similar day on Wednesday, June 25, 2008. ride the veto. Two hours later, 105 device that propels a projectile through AKTI's bill S968 cleared its final hur- Representatives present (of 124 total) reg- the energy of an explosive), a blackjack, a dle when both houses of the South istered their collective voice with a 93-12 metal pipe or pole, or any other type of Carolina legislature voted to overturn the vote to overturn the veto. device, or object which may be used to veto of Governor Mark Sanford. A 2/3 The bill becomes law virtually immedi- inflict bodily injury or death. (Removes majority vote of members present in both ately. Here are the pertinent amended sec- the phrase … “knives with blades longer houses was required for the override. tions: than two inches”.) Since the bill originated in the Senate, Section 16-23-405 of the 1976 Code is Section 16-23-460 of the 1976 Code is amended to read: … (C) The provisions Does Heller Decision Apply to Knives? of this section also do not apply to rifles, By Daniel C. Lawson, Esquire shotguns, dirks, slingshots, metal knuck- les, knives, or razors unless they are used The landmark decision by the United century meaning is no different from the with the intent to commit a crime or in States Supreme Court in the case of meaning today. -

S T a T E O F N E W Y O R K S. 6483--A A

S T A T E O F N E W Y O R K ________________________________________________________________________ S. 6483--A A. 9042--A S E N A T E - A S S E M B L Y January 19, 2016 ___________ IN SENATE -- Introduced by Sen. SAVINO -- read twice and ordered print- ed, and when printed to be committed to the Committee on Codes -- committee discharged, bill amended, ordered reprinted as amended and recommitted to said committee IN ASSEMBLY -- Introduced by M. of A. QUART, COLTON, GOTTFRIED, O'DONNELL, MILLER -- Multi-Sponsored by -- M. of A. COOK -- read once and referred to the Committee on Codes -- committee discharged, bill amended, ordered reprinted as amended and recommitted to said commit- tee AN ACT to amend the penal law, in relation to the definitions of a switchblade knife and a gravity knife THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, REPRESENTED IN SENATE AND ASSEM- BLY, DO ENACT AS FOLLOWS: 1 Section 1. Subdivisions 4 and 5 of section 265.00 of the penal law are 2 amended to read as follows: 3 4. "Switchblade knife" means any knife which has a blade which opens 4 automatically by hand pressure applied to a button, spring or other 5 device in the handle of the knife. "SWITCHBLADE KNIFE" DOES NOT INCLUDE 6 A KNIFE THAT HAS A SPRING, DETENT, OR OTHER MECHANISM DESIGNED TO CREATE 7 A BIAS TOWARD CLOSURE AND THAT REQUIRES EXERTION APPLIED TO THE BLADE BY 8 HAND, WRIST, OR ARM TO OVERCOME THE BIAS TOWARD CLOSURE AND OPEN THE 9 KNIFE. -

OKCA 29Th Annual • April 17-18

KNIFEOKCA 29th Annual SHOW • April 17-18 Lane County Fairgrounds & Convention Center • Eugene, Oregon April 2004 Ourinternational membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” YOU ARE INVITEDTO THE OKCA 29th ANNUAL KNIFE SHOW & SALE In the freshly refurbished EXHIBIT HALL. Now 470 Tables! You Could Win... a new Brand Name knife or other valuable prize, just for filling out a door prize coupon. Do it now so you don't forget! You can also... buy tickets in our Saturday (only) RAFFLE for chances to WIN even more fabulous knife prizes. Stop at the OKCA table before 5:00 p.m Saturday. Tickets are only $1 each, or 6 for $5. Free Identification & Appraisal Ask for Bernard Levine, author of Levine's Guide to Knives and Their Values, at table N-01. ELCOME to the Oregon Knife At the Show, don't miss the special live your name to be posted near the prize showcases Collectors Association Special Show demonstrations Saturday and Sunday. This (if you miss the posting, we will MAIL your WKnewslettter. On Saturday, April 17 year we have Martial Arts, Scrimshaw, prize). and Sunday, April 18, we want to welcome you Engraving, Knife Sharpening, Blade Grinding and your friends and family to the famous and Competition, Knife Performance Testing and Along the side walls, we will have more than a spectacular OREGON KNIFE SHOW & SALE. Flint Knapping. New this year: big screen live score of MUSEUM QUALITY KNIFE AND Now the Largest Knife Show in the World! TV close-ups of the craftsmen at work. And SWORD COLLECTIONS ON DISPLAY for don't miss the FREE knife identification and your enjoyment, in addition to our hundreds of The OREGON KNIFE SHOW happens just appraisal by renowned knife author tables of hand-made, factory, and antique knives once a year, at the Lane County Fairgrounds & BERNARD LEVINE (Table N-01). -

Cert Petition

No. ________ In The Supreme Court of the United States JOHN COPELAND, PEDRO PEREZ, AND NATIVE LEATHER, LTD., Petitioners, -V- CYRUS VANCE, JR. IN HIS OFFICIAL CAPACITY AS THE NEW YORK COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY, AND CITY OF NEW YORK, Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI DANIEL L. SCHMUTTER Counsel of Record HARTMAN & WINNICKI, P.C. 74 Passaic Street Ridgewood, NJ 07450 (201) 967-8040 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioners January 14, 2019 QUESTION PRESENTED In United States v. Salerno, 481 U.S. 739, 745 (1987), this Court held that to maintain a facial challenge, a plaintiff must establish that “no set of circumstances exists under which the Act would be valid.” 481 U.S. at 745. The federal courts of appeals are starkly split on the question of whether this rule was relaxed by the Court in the context of vagueness cases in Johnson v. United States, 135 S. Ct. 2551 (2015), and Sessions v. Dimaya, 138 S. Ct. 1204 (2018). The Fourth and Eighth Circuits have answered in the affirmative. See Kolbe v. Hogan, 849 F.3d 114, 148 fn.19 (4th Cir. 2017); United States v. Bramer, 832 F.3d 908 (8th Cir. 2016). By contrast, the Second Circuit expressly insisted below that no such relaxation has taken place. Copeland v. Vance, 893 F.3d 101, 113 fn.3 (2d Cir. 2018). The question presented is: Whether a plaintiff need show that a law is vague in all of its applications to succeed in a facial vagueness challenge. -

Impact Assessment Knives

Title: Proposals to strength knife legislation IA No: HO0292 Impact Assessment (IA) RPC Reference No: Date: 14 Oct 2017 Lead department or agency: Home Office Stage: Consultation Other departments or agencies: Source of intervention: Domestic Type of measure: Primary legislation Contact for enquiries: [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: Awaiting Scrutiny Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Business Net Net cost to business per One-In, Business Impact Target Present Value Present Value year (EANDCB in 2014 prices) Three-Out Status -£7.66 million N/K N/K N/K No BIT Targer What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Knife crime recorded by the police has been increasing since late 2014 and it is now above the level of knife crime in 2010. The increases were initially due to improvements in police recording of crime, but recent figures are thought to reflect real increases in some parts of the country. The Government has been taking action, legislating where necessary (e.g. banning zombie knives), working with retailers to enforce sales restrictions, and preventing knife crime through working with voluntary sector groups. However, as part of this wide range approach, we also want to strengthen primary legislation to respond to concerns and to provide the police with more powers. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? The legislative proposals will support public safety and give police the powers they need to tackle knife crime. We are concerned about young people carrying knives and we know that young people are currently able to use online retailers to obtain knives without being subject to the age ID checks which would be applied in store; we want to tackle this issue. -

Offensive Weapons Bill Submission to Committee John Pidgeon

Written evidence submitted by CART (Coleshill Auxiliary Research Team) (OWB91) Please find attached my expert witness statement to the Committee. I am an Author and Historical Researcher and one of the leading experts in Military and Antique Knives with 45 years experience. The submission is made on behalf of CART (Coleshill Auxiliary Research Team), a group of like-minded volunteers whom carryout research and educate the public in the activities of the British Resistance. There are a number of discrepancies and omissions between the Bill and its associated Explanatory Notes, which make the meaning unclear. I have left these out of the main submission, as they are admin errors. Clause 22 of the Offensive Weapons Bill 17/19 deals with items prohibited under Section 141 CJA 1988 making them additionally illegal to possess in private adds the defence of “historical importance”. There is no such entry, further explanation or definition of “historical importance" in the corresponding Notes under Clause 22. Clauses 19 and 20 of the Offensive Weapons Bill 17/19 deal with gravity knives and flick knives under Restriction of Offensive Weapons Act 1959 adding possession to the new Bill but with no additional defences. However the corresponding Notes on Cause 20 refer to Section 141 of CJA 1988, which does have defences and the new defence of “historic importance”. Additionally Clause 23 sub clause 110 of the Notes specifically states the defences of Section 141 CJA 1988 apply to Clause 20 of the Offensive Weapons Bill 17/19. Yours sincerely, John Pidgeon July 2018 Summary 1. I have limited my expert witness statement to the proposed ban on ownership of certain weapons and the defences as laid out in clauses 20, 22 and 23. -

Plaintiff-Appellee's Opposition to DA's Motion

Case 19-1129, Document 34, 07/08/2019, 2601906, Page1 of 27 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT ------------------------------------------------------------X JOSEPH CRACCO, DECLARATION Plaintiff-Appellee, IN OPPOSITION TO THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S MOTION - against - TO DISMISS AND VACATE CYRUS R. VANCE, JR.,, Case 19-1129 Defendant-Appellant. THE CITY OF NEW YORK, Police Officer JONATHAN CORREA, Shield 7869, Transit Division District 4, and Police Officer JOHN DOE, Defendants. ------------------------------------------------------------X James M. Maloney, an attorney at law admitted to practice before this Honorable Court, declares under penalty of perjury as follows: 1. I am the attorney of record for Plaintiff-Appellee, and submit this declaration, together with the exhibit and memorandum that follow, in opposition to the motion by Defendant-Appellant (2d Cir. ECF Document 30) to vacate four (4) judgments and/or opinions of the court below in this case and to dismiss this appeal as moot. See “Declaration in Support of the District Attorney’s Motion to Dismiss and Vacate” (hereinafter, “Krasnow Dec.”) at ¶ 1. 2. Although the recent enactment, Assembly Bill 5944, removed “gravity Case 19-1129, Document 34, 07/08/2019, 2601906, Page2 of 27 knife” from the list of prohibited instruments contained in New York Penal Law § 265.01, it did not remove the statutory definition of “gravity knife” from Penal Law § 265.00, where it remains at subsection 5. A “gravity knife” is defined as “any knife which has a blade which is released from the handle or sheath thereof by the force of gravity or the application of centrifugal force which, when released, is locked in place by means of a button, spring, lever or other device.” N.Y. -

OKCA 33Rd Annual • April 12-13

OKCA 33rd Annual • April 12-13 KNIFE SHOW Lane Events Center & Fairgrounds • Eugene, Oregon April 2008 Ourinternational membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” You Could Win... a new Brand Name knife or other valuable prize, just for filling out a door prize coupon. Do it now so you don't forget! You can also... buy tickets in our Saturday (only) RAFFLE for chances to WIN even more fabulous knife prizes. Stop at the OKCA table before 4:00 p.m. Saturday. Tickets are only $1 each, or 6 for $5. Join in the Silent Auction... Saturday only we will have a display case filled with very special knives for bidding. Put in your bid and see if you will take home a very special prize. Free Identification & Appraisal Ask for Bernard Levine, author of Levine's Guide to Knives and Their Values, at table N01. ELCOME to the Oregon Knife have Blade Forging, Japanese Sword also have a raffle Saturday only.Anyone can enter Collectors Association Special Show Demonstrations, Japanese Sword History the raffle. See the display case by the exit to WKnewslettter. On Saturday, April 12 Seminars, Scrimshaw, Engraving, Knife purchase tickets and see the items that you could and Sunday, April 13, we want to welcome you Sharpening, Blade Grinding Competition, win. and your friends and family to the famous and Wood Carving and Flint Knapping. And don't spectacular OREGON KNIFE SHOW & SALE. miss the FREE knife identification and Along the side walls, we will have more than a NowtheLargestKnife ShowintheWorld! appraisal by knife author BERNARD LEVINE score of MUSEUM QUALITY KNIFE AND (Table N01).