BALKAN Nationalism AFTER1989

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yugoslav Macedonia

Anticommunist, but Macedonian: Politics of Memory in Post-Yugoslav Macedonia (5,579 words) “The dead heroes of Macedonia, albeit as ghosts, will rise against all of you who will decide to give your support to this harmful plan. Through the destruction of the monuments of the antifascist war, you destroy the present and the future of our country .” 1 In the famous Lieux de mémoire , the French historian Pierre Nora outlines the main forms of a worldwide process identified by him as a ‘global upsurge of memory.’ These involve the critique of the official versions of history and the return to what was hidden away; the search for an obfuscated or ‘confiscated’ past; the cult of ‘roots’ and the development of genealogical investigations; the boom in fervent celebrations and commemorations; legal settlement of past ‘scores’ between different social groups; the growing number of all kinds of museums; the rising need for conservation of archives but also for their opening to the public; and the new attachment to ‘heritage’ ( patrimoine in French).2 It is easy to find many similar symptoms in the contemporary public space of the Republic of Macedonia. Since its independence in 1991, political and academic entrepreneurs have promoted, sometimes with opposite goals, new versions of national history. The cult of millenary roots and the genealogical and ‘ethnogenetical’ (para-)historiographic genres are becoming ever more popular and in some circles at least, the heritage of ancient Macedonia and its famous rulers – Philip and Alexander – is embraced as a token of national pride. 3 In 2003, an impressively long list of commemorations marked the centennial of the anti-Ottoman St. -

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace

The Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and the Idea for Autonomy for Macedonia and Adrianople Thrace, 1893-1912 By Martin Valkov Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Prof. Tolga Esmer Second Reader: Prof. Roumen Daskalov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2010 “Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author.” CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract The current thesis narrates an important episode of the history of South Eastern Europe, namely the history of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization and its demand for political autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. Far from being “ancient hatreds” the communal conflicts that emerged in Macedonia in this period were a result of the ongoing processes of nationalization among the different communities and the competing visions of their national projects. These conflicts were greatly influenced by inter-imperial rivalries on the Balkans and the combination of increasing interference of the Great European Powers and small Balkan states of the Ottoman domestic affairs. I argue that autonomy was a multidimensional concept covering various meanings white-washed later on into the clean narratives of nationalism and rebirth. -

The Tobacco Fortress

THE TOBACCO FORTRESS: “ASENOVGRAD KREPOST” AND THE POLITICS OF TOBACCO IN INTERWAR BULGARIA An NCEEER Working Paper by Mary Neuberger University of Texas National Council for Eurasian and East European Research University of Washington Box 353650 Seattle, WA 98195 [email protected] http://www.nceeer.org/ TITLE VIII PROGRAM Project Information* Principal Investigator: Mary Neuberger NCEEER Contract Number: 824-11 Date: August 5, 2010 Copyright Information Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funded through a contract or grant from the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research (NCEEER). However, the NCEEER and the United States Government have the right to duplicate and disseminate, in written and electronic form, reports submitted to NCEEER to fulfill Contract or Grant Agreements either (a) for NCEEER’s own internal use, or (b) for use by the United States Government, and as follows: (1) for further dissemination to domestic, international, and foreign governments, entities and/or individuals to serve official United States Government purposes or (2) for dissemination in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the United States Government granting the public access to documents held by the United States Government. Neither NCEEER nor the United States Government nor any recipient of this Report may use it for commercial sale. * The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract or grant funds provided by the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, funds which were made available by the U.S. Department of State under Title VIII (The Soviet-East European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). -

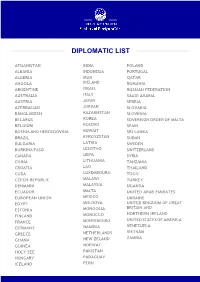

Diplomatic List

DIPLOMATIC LIST AFGANISTAN INDIA POLAND ALBANIA INDONESIA PORTUGAL ALGERIA IRAN QATAR ANGOLA IRELAND ROMANIA ARGENTINE ISRAEL RUSSIAN FEDERATION AUSTRALIA ITALY SAUDI ARABIA AUSTRIA JAPAN SERBIA AZERBAIJAN JORDAN SLOVAKIA BANGLADESH KAZAKHSTAN SLOVENIA BELARUS KOREA SOVEREIGN ORDER OF MALTA BELGIUM KOSOVO SPAIN BOSNIA AND HERCEGOVINA KUWAIT SRI LANKA BRAZIL KYRGYZSTAN SUDAN BULGARIA LATVIA SWEDEN BURKINA FASO LESOTHO SWITZERLAND CANADA LIBYA SYRIA CHINA LITHUANIA TANZANIA CROATIA LAO THAILAND CUBA LUXEMBOURG TOGO CZECH REPUBLIC MALAWI TURKEY DENMARK MALAYSIA UGANDA ECUADOR MALTA UNITED ARAB EMIRATES EUROPEAN UNION MEXICO UKRAINE EGYPT MOLDOVA UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND ESTONIA MONGOLIA NORTHERN IRELAND FINLAND MOROCCO UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FRANCE MONTENEGRO VENEZUELA GERMANY NAMIBIA VIETNAM GREECE NETHERLANDS ZAMBIA GHANA NEW ZELAND GUINEA NORWAY HOLY SEE PAKISTAN HUNGARY PARAGUAY ICELAND PERU ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGANISTAN Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 57 “Simeonovsko shosse” street, Res. 3, 1700 Sofia telephone: +359 2 962-74-76 / +359 2 962-51-93 fax: +359 2 962-74-86 e-mail: [email protected] Opening Hours: Monday-Friday 09:00 - 16:00 Consular Section: Monday and Thursday 09:00 - 16:00 National Holiday: 19 August- Independence Day Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Mr. Mohammad Khalil Kargar, m. 1st Secretary REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA Embassy of the Republic of Albania Slavej Planina 2, 1000 Skopje telephone: +389 2 3246 726 fax: +389 2 3246 727 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.albanianembassy.org.mk Visa Office telephone: +389 2 324 6726 – ext. 105 Opening Hours: Monday-Friday 08.00 - 16.00 Consular Section: 10.00 - 12.00 National Holiday: National Day, November 28 His Excellency Mr. -

Pdf; Despina Angelovska, (Mis-)Representa- Tions of Transitional Justice

Südosteuropa 66 (2018), no. 4, pp. 451-480 PAUL REEF Macedonian Monument Culture Beyond ‘Skopje 2014’ Abstract. While recent studies on Macedonia have mostly focused on ‘Skopje 2014’ as a unique- ly excessive project of nation-building, this article analyses local developments in monument culture elsewhere in Macedonia. Disentangling the processes of nation-building since the Ohrid Agreement of 2001, the author distinguishes three coexisting, but competing, reper- toires of monument culture, namely a Yugoslav, a Macedonian, and an Albanian one. Each repertoire has been closely associated with ethnicity and the legitimation of ethnopolitical claims, as well as party politics and ideology. The past has continued to divide Macedonians. The author argues that these divisions in Macedonian monument culture reflect the compet- ing and diverging Albanian and Macedonian historical narratives, and amount to effectively mutually exclusive ethnic and ideological nation-building efforts in post-Ohrid Macedonia. Paul Reef is a Research Master’s student in Historical Studies at the Institute for Historical, Literary and Cultural Studies at Radboud University Nijmegen and a Research Intern for the project ‘The Invention of Bureaucracy’ at the University of Aarhus. Beyond ‘Skopje 2014’ ‘Skopje 2014’ was one of the largest urban-renewal and -construction pro- grammes in Europe since the fall of communism. It aimed at transforming Skopje from a brutalist Yugoslav city into a modern, attractive, neoclassicist capital up to European standards. The project included well over a hundred buildings, from opera halls and hotels to orthodox churches and museums. Additionally, Yugoslav-era edifices were either destroyed or refitted with -neo classical façades. -

The Solun Assassins

The Solun Assassins By Krste Bitoski (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) The Solun Assassins Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2017 by Krste Bitoski & Risto Stefov e-book edition ************ August 18, 2017 -- In honour of Macedonian Army Day -- I would like to dedicate the translated version of this book to my friends in the Macedonian military and to all Macedonian officers and soldiers who fought and are fighting to protect Macedonia and the Macedonian people. Risto 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..........................................................................................5 PART ONE ..............................................................................10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ASSUMPTIONS ABOUT THE APPEARANCE OF THE GEMIDZHII CIRCLE .......................10 EUROPEAN CAPITAL INVESTED IN MACEDONIA ...............10 ECONOMIC REVIEW OF VELES ................................................17 FORMING AND SHAPING THE GEMIDZHII CIRCLE .............20 IMAGES OF THE REVOLUTIONARIES .....................................31 Iordan Popiordanov-Ortse (1881-1903)...........................................31 Kosta Ivanov Kirkov -

The Museum of the Macedonian Struggle and the Shifting Post-Socialist Historical Discourses in Macedonia

Displaying a contested past: The Museum of the Macedonian Struggle and the shifting post-socialist historical discourses in Macedonia By Naum Trajanovski Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Michael Laurence Miller CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2016 Abstract The project examines the newly emerged Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, as an exceptional case of a museum regarding its historical narrative and the visual representation of the narrative structure. The main analytical focus will be put on the historical narrative presented in the Museum on one hand, as part of the meta-historical narrative conducted by VMRO-DPMNE‟s government in contemporary Republic of Macedonia, and on the other hand, the functional purpose, the political and institutional aftermath of the Museum. Therefore, it will be argued that the Museum brings a particularly univocal, top-down version of one particular historical narrative, as a discursive feature with legitimizing political function. Finally, the thesis will focus on the particular need to establish museum of this kind, and moreover, will engage with the question why a museum as an institution and particular form of institutionalized memory is propounded as a solution in the contemporary Macedonian socio-political context. Key words: Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, Macedonia, historical museums, national narration, contested past CEU eTD Collection ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my supervisor Professor Michael Laurence Miller, for the guidance during the writing process and for the constructive comments. I wish to acknowledge the help of the faculty and the staff members of the CEU Nationalism Studies Program. -

The Macedonian National Movement in the Pirin Part of Macedonia

Atanas Kiryakov and Aleksandar Donski MACEDONIA RISES THE MACEDONIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PIRIN PART OF MACEDONIA 1 Atanas KIRYAKOV and Aleksandar DONSKI MACEDONIA RISES THE MACEDONIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PIRIN PART OF MACEDONIA Published by the Macedonian Literary Association “Grigor Prlichev”, Sydney – Australia In collaboration with Institute for History and Archaeology “Goce Delcev” University - Stip Republic of Macedonia For the Publisher: Dushan RISTEVSKI * * * Translated by: Ljubica Bube DONSKA David RILEY (Great Britain) *** Macedonian Literary Association “Grigor Prlichev” P.O. Box 227 Rockdale NSW 2216 – Australia * * * Copyright by: Atanas Kiryakov and Aleksandar Donski National Library of Australia card number and ISBN 978-0-9808479-8-7 December, 2012 2 The book that you have in front of you presents a part of the documentation from the personal archive of the Macedonian activist Atanas Kiryakov from Blagoevgrad, which is dedicated to the struggle for the basic human and national rights of the Macedonians in the Pirin part of Macedonia and Bulgaria. People and events that Kiryakov himself directly or indirectly has met or attended are mentioned in here. This means that the book does not claim to contain ALL the documents from the struggles of the Macedonians under Pirin or that it contains all Macedonian activities, so the rest of the documents, notable people and descriptions of this struggle, remain to be published in later issues. From the editors 3 MAIN SPONSOR OF THE BOOK: Macedonian Orthodox Community of Australia 4 INSTEAD OF AN INTRODUCTION Before we move on to the basic subject of this book, we have to explain why the Macedonians were never Bulgarian, nor did they have ethnic Bulgarian origins, as it is claimed by the majority of Bulgarian governments and official organs. -

The Uncomfortable Truth About the Macedonian Political Organization

The Uncomfortable Truth about the Macedonian Political Organization Victor Sinadinoski 1 Copyright © 2018 by Victor Sinadinoski All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 9781728827803 2 INTRODUCTION The Macedonian Political Organization (MPO) (presently known as the Macedonian Patriotic Organization) is perhaps one of the most controversial Macedonian Diaspora organizations. On one hand, its official stance has always been the realization of a ‘Macedonia for the Macedonians’; its members and followers promote the Macedonian culture; and they call themselves Macedonians. On the other hand, the MPO leadership has often negated the existence of ethnic Macedonians and a Macedonian language, and the MPO bylaws claim that the term ‘Macedonian’ has no ethnic connotation. Moreover, the bylaws list ethnic groups that hail from Macedonia, which conspicuously does not include ethnic Macedonians.1 To the MPO leadership and many of its members, the ethnic Macedonian identity is an invention of Yugoslav Communist leader Josip Broz Tito. Yes, the MPO indeed says it is an organization of Macedonians. By this, however, it only means that its members originate from geographical Macedonia and that their language and ethnic identity is Bulgarian. Thus, while on certain levels the MPO can be considered a ‘pro-Macedonia’ organization, it cannot be classified as a ‘pro-Macedonian’ group.2 Some readers may therefore rightfully find it puzzling that I have expended much effort in writing a book about the MPO. -

Puni Tekst: Hrvatski, Pdf (2

Ž. Karaula, Pismo vođe VMRO-a Todora Aleksandrova Stjepanu Radiću 1924. godine, Arh. vjesn., god. 51 (2008), str. 313-323 Željko Karaula Banovine Hrvatske 26b Bjelovar PISMO VOĐE VMRO-a TODORA ALEKSANDROVA STJEPANU RADIĆU 1924. GODINE UDK 94(497.7:497.5)“1924“(044) Pregledni rad U povijesnoj literaturi hrvatske i makedonske provenijencije kontakti Stjepana Radića s VMRO-om nisu dosad dovoljno istraženi, a ako se i spominju, dobivaju neki pustolovno-romantični, revolucionarni prizvuk. Ovdje se objavljuje jedno pismo koje je vođa VMRO-a Todor Aleksandrov napisao Stjepanu Radiću sredinom kolo- voza 1924. godine. U pismu Todor Aleksandrov odgovara na Radićev članak objav- ljen u »Balkanskoj Federaciji« od 15. kolovoza 1924. godine te ga pokušava nago- voriti da mu se pridruži u oružanom otporu prema Beogradu i njegovoj hegemoniji u Kraljevini SHS. Ključne riječi: Stjepan Radić, Todor Aleksandrov, VMRO, Svibanjska deklara- cija, Kominterna, makedonsko pitanje Način ulaska hrvatskog i makedonskog naroda u novu državu Kraljevstvo Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca 1918. godine bio je dijametralno suprotan. Dok je hrvatski narod ušao u zajedničku državu kao »ravnopravni faktor« i kao jedan od tri priznata »plemena« jednoga jugoslavenskoga naroda (što se uostalom vidi i u samom nazivu države), makedonskom narodu u tom državnom uređenju nije bio priznat nikakav nacionalni subjektivitet. Kao što je poznato, stvaranjem Kraljevstva SHS 1918. godine u osnovi je sankcionirana podjela Makedonije izvršena poslije poraza Tur- skog carstva u balkanskim ratovima 1912. i 1913. godine. Vardarski dio Makedonije koji je pripao novoj državi Kraljevstvu SHS podvrgnut je denacionalizatorskoj i asimilatorskoj politici velikosrpskih krugova i elita pa je ta politika dovela do toga da je Makedonija u sustavu stare Jugoslavije postala »Južna Srbija«. -

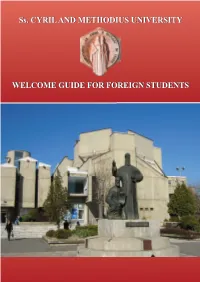

GUIDE for FOREIGN STUDENTS Ss. CYRIL and METHODIUS

Ss.Ss. CYRILCYRIL ANDAND METHODIUSMETHODIUS UNIVERSITYUNIVERSITY WELCOME GUIDE FOR FOREIGN STUDENTS Ss. CYRIL AND METHODIUS UNIVERSITY IN SKOPJE TABLE OF CONTENTS WELCOME Rector’s welcome IRO’s welcome REPUBLIC OF NORTH MACEDONIA AND THE CITY OF SKOPJE GENERAL INFORMATION ON Ss. CYRIL AND METHODIUS UNIVERSITY IN SKOPJE List of faculties and research institutes Erasmus+ coordinators at faculty level Academic information PRE-DEPARTURE ARRANGEMENTS Visa procedure Housing Health insurance UPON ARRIVAL ARRANGEMENTS USEFUL INFORMATION 1 Ss. CYRIL AND METHODIUS UNIVERSITY IN SKOPJE MILENIUM OLD TRADITION OF EDUCATION AND CULTURE The Holy brothers Cyril and Methodius “Wise Thoughts of Konstantin the Philosopher” – an ancient Slavic script 2 Ss. CYRIL AND METHODIUS UNIVERSITY IN SKOPJE Rector’s welcome Dear students, Dear colleagues, International cooperation and internationalization is one of the top priorities and strategic determinations of the Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia. The establishment, nurturing and development of international cooperation with renowned universities abroad and international organizations in the field of higher education remains our permanent commitment, as witnessed by more than 380 bilateral agreements with highly ranked foreign universities on all continents, membership in international university networks and other organizations of relevance for the development of education, science and culture. The findings gained through the long-term cooperation have determined the directions of a strategic planning and the necessary reforms of the University in accordance with European integration and globalization processes that will enable our international recognition and reputation in the academic community. The Ss. Cyril and Methodius University with great enthusiasm is implementing the Erasmus+ program in order to enable its students and academic staff to gain international experience at EU universities. -

Kyril Drenikoff Papers, Date (Inclusive): 1849-2002 Collection Number: 88009 Creator: Drenikoff, Kyril Extent: 223 Manuscript Boxes, 42 Oversize Boxes, 1 Cu

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6g5013m5 No online items Register of the Kyril Drenikoff Papers Prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2003 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Kyril Drenikoff 88009 1 Papers Register of the Kyril Drenikoff Papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] Prepared by: Natasha Porfirenko Date Completed: 2002 Encoded by: ByteManagers using OAC finding aid conversion service specifications © 2003 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Kyril Drenikoff papers, Date (inclusive): 1849-2002 Collection number: 88009 Creator: Drenikoff, Kyril Extent: 223 manuscript boxes, 42 oversize boxes, 1 cu. ft. box, 14 card file boxes, 7 slide boxes, 2 oversize folders, 2 motion picture film reels, 22 phonotape cassettes, 1 videotape cassette, 106 phonorecords, 1 microfilm reel, memorabilia (125 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, writings, conference proceedings, reports, bulletins, serial issues, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, maps, other pictorial materials, and memorabilia, relating to the history and culture of Bulgaria, activities of the post-World War II Bulgarian émigré community, and activities of the World Anti-Communist League, the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations and other anti-communist organizations. Includes diaries of Georgi Drenikov, father of K. Drenikoff, and commander of the Bulgarian Air Force during World War II.