THE BIGGEST CON How the Government Is Fleecing You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

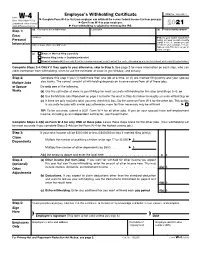

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY March 5, 1996 In

* * * PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY March 5, 1996 In accordance with the Warrant the polls were opened at 7:00 a.m. and closed at 8:00 p.m. The voters cast their ballots in their respective precincts. The results were as follows: DEMOCRATIC PARTY 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 TOTAL PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE Bill Clinton 24 59 24 21 39 81 71 57 63 25 464 Lyndon N. LaRouche Jr 0 3 0 0 0 2 1 5 1 1 13 No Preference 1 1 1 0 3 2 0 5 3 1 17 All Others 3 1 0 0 1 0 0 4 0 2 11 Blanks 0 0 3 0 2 0 2 2 2 0 11 TOTAL 28 64 28 21 45 85 74 73 69 29 516 STATE COMMITTEE MAN Stanley C. Rosenberg 23 55 27 20 35 74 61 63 61 27 446 Blanks 5 9 1 1 10 11 13 10 8 2 70 TOTAL 28 64 28 21 45 85 74 73 69 29 516 STATE COMMITTEE WOMAN Mary L. Ford 22 48 22 17 29 60 56 55 52 22 383 All Others 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Blanks 6 16 6 4 16 25 18 18 17 7 133 TOTAL 28 64 28 21 45 85 74 73 69 29 516 TOWN COMMITTEE Mary Sidney Treyz 11 17 16 11 17 15 31 26 40 24 208 Florence C. Frank 10 21 16 12 19 22 28 28 45 21 222 Dolores D. -

IRS Publication 4128, Tax Impact of Job Loss

Publication 4128 Tax Impact of Job Loss The Life Cycle Series A series of informational publications designed to educate taxpayers about the tax impact of significant life events. Publication 4128 (Rev. 5-2020) Catalog Number 35359Q Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service www.irs.gov Facts JOB LOSS CREATES TAX ISSUES References The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) recognizes that the loss of a job may • Publication 17, Your create new tax issues. The IRS provides the following information to Federal Income Tax (For assist displaced workers. Individuals) • Severance pay and unemployment compensation are taxable. • Publication 575, Payments for any accumulated vacation or sick time are also Pension and Annuity taxable. You should ensure that enough taxes are withheld from Income these payments or make estimated payments. See IRS Publication 17, Your Federal Income Tax, for more information. • Publication 334, Tax Guide for Small • Generally, withdrawals from your pension plan are taxable unless Businesses they are transferred to a qualified plan (such as an IRA). If you are under age 59 1⁄2, an additional tax may apply to the taxable portion of your pension. See IRS Publication 575, Pension and Annuity Income, for more information. • Job hunting and moving expenses are no longer deductible. • Some displaced workers may decide to start their own business. The IRS provides information and classes for new business owners. See IRS Publication 334, Tax Guide for Small Businesses, for more information. If you are unable to attend small business tax workshops, meetings or seminars near you, consider taking Small Business Taxes: The Virtual Workshop online as an alternative option. -

Section 5 Explanation of Terms

Section 5 Explanation of Terms he Explanation of Terms section is designed to clarify Additional Standard Deduction the statistical content of this report and should not be (line 39a, and included in line 40, Form 1040) T construed as an interpretation of the Internal Revenue See “Standard Deduction.” Code, related regulations, procedures, or policies. Explanation of Terms relates to column or row titles used Additional Taxes in one or more tables in this report. It provides the background (line 44b, Form 1040) or limitations necessary to interpret the related statistical Taxes calculated on Form 4972, Tax on Lump-Sum tables. For each title, the line number of the tax form on which Distributions, were reported here. it is reported appears after the title. Definitions marked with the symbol ∆ have been revised for 2015 to reflect changes in Adjusted Gross Income Less Deficit the law. (line 37, Form 1040) Adjusted gross income (AGI) is defined as total income Additional Child Tax Credit (line 22, Form 1040) minus statutory adjustments (line 36, (line 67, Form 1040) Form 1040). Total income included: See “Child Tax Credit.” • Compensation for services, including wages, salaries, fees, commissions, tips, taxable fringe benefits, and Additional Medicare Tax similar items; (line 62a, Form 1040) Starting in 2013, a 0.9 percent Additional Medicare Tax • Taxable interest received; was applied to Medicare wages, railroad retirement com- • Ordinary dividends and capital gain distributions; pensation, and self-employment income that were more than $200,000 for single, head of household, or qualifying • Taxable refunds of State and local income taxes; widow(er) ($250,000 for married filing jointly, or $125,000 • Alimony and separate maintenance payments; for married filing separately). -

Hanover Annual Report FY 1996

~ ~"'° ~ ~ ~ t: lr) ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ t-..j ~ ~ ~ ;::~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ . ~ ~ N ~ ~ ~ ~ ;::: ~ ~ ONEHUNDRED AND FORTY-FOURTH ANNUAL REPORT of the OFFICERS AND COMMITTEES of the TOWN OF HANOVER FOR THE YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1996 In Memoriam Michael J. Ahern 1925 - 1996 Veterans' A3enl francis J. Curran 1940 - 1996 Coordinalor of Education, Technolcsical Media (?5 Libraries lianover Middle &hool Dale A. Lochiallo 1948 - 1996 Elderly &rvices Direclor Council on A3in8 Muriel L. Mdlman 1919 - 1996 Librarian John Curlis free Library Peler Q_ Melanson 1947 - 1996 Dispalcher - J\ssislanl 6upervisor Emef8ency Communicalions Cenler Edward J. Norcoll, Jr. 1912 - 1996 Veterans' A3enl Wilmot Q_ Prall 1929 - 1996 Cuslodian lianover &hool Deparlmenl 2 HANOVER JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL 1971-1972 STUDENT COUNCIL TOWN OF HANOVER PLYMOUTH COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS Tenth Congressional District WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Quincy COUNCILLOR Second Councillor District KELLY A. TIMILTY, Canton STATE SENATOR ROBERTS. CREEDON, JR., Brockton STATE REPRESENTATIVE Fifth Plymouth Representative District JANET W. O'BRIEN, Hanover COUNTY COMMISSIONERS ROBERT J. STONE, Whitman JOSEPH F. McDONOUGH, Scituate PETER G. ASIAF, JR., Brockton Population - Federal Census 11,918 Town Census 12,862 4 ELECTED TOWN OFFICERS SELECTMEN Albert R. Cavanagh 1997 George H. Lewald 1998 Robert J. Nyman 1999 ASSESSORS Robert C. Shea, Chr. 1997 Juleen D. Gantly, resigned* 1998 David C. Bond 1999 *Harald D. Carlson TOWNCLERK William F. Flynn 1998 TAX COLLECTOR Joan T. Port 1998 SCHOOL COMMITTEE Frederick L. Briggs, Chr. 1997 Edward F. Mc Vinney, Vice Chr. 1997 Joseph Bellantoni 1998 John D. Guenard 1999 Michael J. Cianciola, Sec. BOARD OF HEALTH Joseph F. Casna, Jr., Chr. 1997 Leslie J. Molyneaux 1998 Jerome D. -

Results for March 26, 1996 Primary Election

Susan B. Aitderisoit '» County €lcrk/R«|^strar of Voters STATEMENT OF VOTES CAST AT THE PRIMARY ELECTION HELD ON MARCH 26, 1996 IN THE COUNTY OF FRESNO STATE OF CALIFORNIA CERTIFICATE OF COUNTY CLERK TO RESULTS OF THE CANVASS STATE OF CALIFORNIA) )ss. County of Fresno ) I, SUSAN B ANDERSON, County Clerk/Registrar of Voters of the County of Fresno, State of California, do hereby certify that pursuant to the provisions of Section 15301 et seq of the Elections Code of the State of California, I did canvass the returns of the vote cast in the County of Fresno, at the election held on March 26, 1996, for the Federal, State and Local Offices and Measures submitted to the vote of the voters, and that the Statement of the Vote Cast, to which this certificate is attached, shows the whole number of votes cast in the said county and in each ofthe respective precincts therein, and that the totals of the respective columns and the totals shown for the offices are full, true and correct. WniMESS my hand and Official Seal this 11th day of April, 1996. SUSAN B. ANDERSON County Clerk/Registrar of Voters N(^RMA LOGAN/ ^ Assistant Registrar of Voters FRESNO COUNTY - DIRECT PRIMARY ELECTION PAGE 1 MARCH 26. 1996 PRINTED ON 04/11/96 AT 12.09.15 FINAL REPORT OFFICIAL REPORT NUMBER 11 I PRESIDENT OEM 649/649 I PRESIDENT OEM 472/472 I U S REPRESENTATIVE OEM I VOTE FOR 1 I 19TH DIST VOTE FOR 1 I 19TH DIST VOTE FOR 1 I BILL CLINTON 49396 89.6 I BILL CLINTON 36870 89.5 I PAUL BARILE 29034 99.8 I I LYNDON H. -

Income – Wages, Interest, Etc

Income – Wages, Interest, Etc. Introduction What do I need? □ Form 13614-C This is the first of nine lessons covering the Income section of the □ Publication 4012 taxpayer’s return. A critical component of completing the taxpayer’s return □ Publication 17 is distinguishing between taxable and nontaxable income and knowing Optional: where to report the different types of income on Form 1040. □ Form 1040 Instructions Objectives □ Form 1099-PATR At the end of this lesson, using your resource materials, you will be able to: □ Schedule B • Compute taxable and nontaxable income □ Publication 531 • Distinguish between earned and unearned income □ Publication 550 Publication 926 • Report income correctly on Form 1040 □ □ Publication 970 The following chart will help you select the appropriate topic for your certification course. Certification Course Basic Advanced Military International Wages & Reported Tips Unreported Tip Income Scholarship and Fellowship Income Interest Income Dividend Income Taxable Refunds Alimony Received Business Income Capital Gain/Loss Other Gains/Losses N/A N/A N/A N/A IRA Distributions* Pensions/Annuities* Rental Income Schedule K-1 Distributions Farm Income N/A N/A N/A N/A Unemployment Compensation Social Security Benefits Other Income Foreign Earned Income Military Income *Basic only if the taxable amount is already determined. Income – Wages, Interest, Etc. 8-1 How do I determine taxable and nontaxable income? The Income Quick Reference Guide in the Volunteer Resource Guide, Tab D, Income, includes examples of taxable and nontaxable income. Gross income is all income received in the form of money, goods, property, and services that is not exempt from tax. -

Instructions for Form 1099-DIV (Rev. January 2022)

Note: The draft you are looking for begins on the next page. Caution: DRAFT—NOT FOR FILING This is an early release draft of an IRS tax form, instructions, or publication, which the IRS is providing for your information. Do not file draft forms and do not rely on draft forms, instructions, and publications for filing. We do not release draft forms until we believe we have incorporated all changes (except when explicitly stated on this coversheet). However, unexpected issues occasionally arise, or legislation is passed—in this case, we will post a new draft of the form to alert users that changes were made to the previously posted draft. Thus, there are never any changes to the last posted draft of a form and the final revision of the form. Forms and instructions generally are subject to OMB approval before they can be officially released, so we post only drafts of them until they are approved. Drafts of instructions and publications usually have some changes before their final release. Early release drafts are at IRS.gov/DraftForms and remain there after the final release is posted at IRS.gov/LatestForms. All information about all forms, instructions, and pubs is at IRS.gov/Forms. Almost every form and publication has a page on IRS.gov with a friendly shortcut. For example, the Form 1040 page is at IRS.gov/Form1040; the Pub. 501 page is at IRS.gov/Pub501; the Form W-4 page is at IRS.gov/W4; and the Schedule A (Form 1040/SR) page is at IRS.gov/ScheduleA. -

Policy Document: Peter Kershaw's Tax Approach, Form #08.010

POLICY DOCUMENT: PETER KERSHAW’S TAX APPROACH Last revised: 1/4/2008 Policy Document: Peter Kershaw’s Tax Approach 1 of 47 Copyright Sovereignty Education and Defense Ministry ,http://sedm.org Form 08.010, Rev. 1-4-2008 EXHIBIT:________ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Rebutted version of “The Power to Tax is the Power to Destroy” ................................................. 8 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 8 2.2 Part 1 .......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.3 Part 2 ........................................................................................................................................................................ 21 3 Conclusions ........................................................................................................................................ 42 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Constitutional Provisions 16th Amendment .............................................................................................................................................................. 20, 31 Article IV .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

2020 Instructions for Filing Original and Amended: • Individual Income Tax (IT 1040) • School District Income Tax (SD 100)

• INSTRUCTIONS ONLY • NO RETURNS • hio 2020 Instructions for Filing Original and Amended: • Individual Income Tax (IT 1040) • School District Income Tax (SD 100) Department of hio Taxation tax. hio.gov 2020 Ohio IT 1040 / SD 100 Table of Contents A H N Amended returns ....................................7 Highlights for 2020..................................4 Net operating loss (IT NOL) ..................49 Nonresident credit (IT NRC) ............22-25 B I Nonresident statement (IT NRS) ....12, 48 Business credits ..............................20-22 Individual credits ..............................19-20 Business income Income statements (W-2, 1099) ......38-39 P Business income deduction (IT BUS) ...18 Interest and penalties .....................14, 47 Payment options .....................................5 Definitions and examples ....................9 IT 1040 Completing the top portion ................12 R C General information ..........................10 Refund status .........................................2 College savings (Ohio 529 plan) Line instructions ...........................13-14 Residency .............................................10 Instructions........................................17 Income tax rates and tables .........32-37 Resident credit (IT RC) .........................26 Worksheet .........................................30 J Residency credits .................................21 Retirement income credit......................19 D Joint filing credit ....................................20 Deceased taxpayers ...............................6 -

Form IL-1040 Individual Income Tax Return Or for Fiscal Year Ending / Over 80% of Taxpayers File Electronically

Illinois Department of Revenue *60012201W* 2020 Form IL-1040 Individual Income Tax Return or for fiscal year ending / Over 80% of taxpayers file electronically. It is easy and you will get your refund faster. Visit tax.illinois.gov. Step 1: Personal Information A Enter personal information and Social Security numbers. You must provide the entire Social Security number for you and your spouse. Do not provide a partial Social Security number. - - Your first name and initial Your last name Year of birth Your Social Security number - - Spouse’s first name and initial Spouse’s last name Spouse’s year of birth Spouse’s Social Security number Mailing address (See instructions if foreign address) Apartment number County (Illinois only) City State ZIP or Postal Code Foreign Nation, if not United States (do not abbreviate) B Filing status: Single Married filing jointly Married filing separately Widowed Head of household C Check If someone can claim you, or your spouse if filing jointly, as a dependent. See instructions. You Spouse D Check the box if this applies to you during 2020: Nonresident - Attach Sch. NR Part-year resident - Attach Sch. NR Step 2: Income (Whole dollars only) 1 Federal adjusted gross income from your federal Form 1040 or 1040-SR, Line 11. 1 .00 2 Federally tax-exempt interest and dividend income from your federal Form 1040 or 1040-SR, Line 2a. 2 .00 3 Other additions. Attach Schedule M. 3 .00 4 Total income. Add Lines 1 through 3. 4 .00 Step 3: Base Income 5 Social Security benefits and certain retirement plan income received if included in Line 1. -

Taxation Start Here

Taxation TAXATION DISCUSSION HOME SEARCH SUBJECT INDEX ABOUT US HELP FORUMS SOVEREIGNTY EDUCATION SEDM Website Bookstore START HERE Federal Response Letters (Path to Freedom) State Tax Response Letters Tax Fraud Prevention Manual, Form #06.008 Liberty University TABLE OF CONTENTS: Civil Court Remedies for Sovereigns: Taxation, 1. DISCUSSION FORUMS Litigation Tool #10.002 2. SUBJECT INDEX Responding to a Criminal Tax Indictment, Litigation 3. ACTIVISM AND IMPORTANT EVENTS Tool #10.004 4. NEWS Master File (IMF) Decoder 5. EVIDENCE OF A MASSIVE HOAX Software Liberty Library CD, Form 6. GOVERNMENT AND LEGAL PROFESSION DECEPTION AND PROPAGANDA #11.102 6.1 Mind and thought control and censorship Family Guardian Website 6.2 Rebutted Government Propaganda DVD, Form #11.103 6.3 Legal Profession and Media Propaganda Legal Research DVD, Form #11.201 6.4 Unrebutted Government Propaganda Highlights of American 7. CITIZENSHIP Legal and Political History 7.1 Remedies CD, Form #11.202 Nontaxpayer's Audit 7.2 Legal Research Defense Manual, Form 7.3 Articles #06.011 7.4 Government citizenship resources What to Do When the IRS Comes Knocking, Form 7.5 Christian Citizenship #09.002 (OFFSITE LINK)- 8. ARTICLES/MEDIA How to respond when IRS 8.1 General Articles investigates you Secrets of the Legal 8.2 Christian Tax Articles Industry Book, Litigation 8.3 Tax Profession Corruption Tool #10.003 8.4 IRS Corruption Tax Deposition CD, Form #11.301 9. REMEDIES What Happened to Justice? 9.1 Start your Path to Freedom Here Book, Form #06.012 9.2 General Remedies SSN Policy Manual, Form 9.3 Administrative Remedies #06.013 Sovereignty Forms and 9.4 Legal Remedies Instructions Manual, Form 10.