Deep Are the Roots…”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

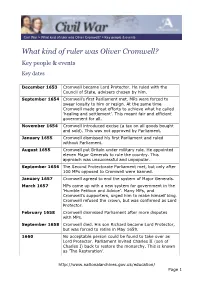

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Remembering King Charles I: History, Art and Polemics from the Restoration to the Reform Act T

REMEMBERING KING CHARLES I: HISTORY, ART AND POLEMICS FROM THE RESTORATION TO THE REFORM ACT T. J. Allen Abstract: The term Restoration can be used simply to refer to the restored monarchy under Charles II, following the Commonwealth period. But it can also be applied to a broader programme of restoring the crown’s traditional prerogatives and rehabilitating the reign of the king’s father, Charles I. Examples of this can be seen in the placement of an equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross and a related poem by Edmund Waller. But these works form elements in a process that continued for 200 years in which the memory of Charles I fused with contemporary constitutional debates. The equestrian statue of Charles I at Charing Cross, produced by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur c1633 and erected in 1675. Photograph: T. J. Allen At the southern end of Trafalgar Square, looking towards Whitehall, stands an equestrian statue of Charles I. This is set on a pedestal whose design has been attributed to Sir Christopher Wren and was carved by Joshua Marshall, Master Mason to Charles II. The bronze figure was originally commissioned by Richard Weston (First Earl of Portland, the king’s Lord High Treasurer) and was produced by the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur in the early 1630s. It originally stood in 46 VIDES 2014 the grounds of Weston’s house in Surrey, but as a consequence of the Civil War was later confiscated and then hidden. The statue’s existence again came to official attention following the Restoration, when it was acquired by the crown, and in 1675 placed in its current location. -

History Term 4

History: Why were Kings back in Fashion by 1660? Year 7 Term 4 Timeline Key Terms Key Questions 1625 Charles I becomes King of England. Civil War A war between people of the same country. What Caused the English Civil War? The Divine Right of Kings — Charles I felt that God had given him Charles closes Parliament. The Eleven Years of This is a belief that the King or Queen is the most 1629 Divine Right of the power to rule and so Parliament should follow his leadership. Tyranny begin. powerful person on earth as God put them into Kings Parliament disagreed with the King over the Divine Right of Kings. power. Parliament believed it should have an important role in running the Charles reopens Parliament in order to raise 1640 country. money for war. Parliament tried to limit the King’s power. Charles responded by Eleven Years Charles I ruled England without Parliament for declaring war on Parliament in 1642. Tyranny eleven years. Charles I attempts to arrest 5 members of 1642 parliament. The English Civil War begins. Why did Parliament Win the War? A government where a King or Queen is the Head of Monarchy 1644 Parliamentarians win the Battle of Marston Moor. State. The New Model Army was created by Parliamentarians in 1645. These soldiers were paid for their services and trained well. 1645 Parliamentarians win the Battle of Naseby. A group in the UK elected by the people. They have Parliament had more money. They controlled the south of England Parliament which was much richer in resources. -

British House of Commons (1810) MUNUC 33 ONLINE 1 British House of Commons (1810) | MUNUC 33 Online

British House of Commons (1810) MUNUC 33 ONLINE 1 British House of Commons (1810) | MUNUC 33 Online TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ LETTER FROM THE CRISIS DIRECTOR…………………………………………..3 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR………………………………………………………. 5 COMMITTEE OVERVIEW………………………………………………………..7 HISTORY OF BRITAIN………………………………………………..………… 9 STATEMNT OF THE PROBLEM………………………………………..……….. 23 BLOC POSITIONS…………………..………………………………..……….. 30 APPENDIX…………………………………………..…………………………..31 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………….. 34 2 British House of Commons (1810) | MUNUC 33 Online LETTER FROM THE CRISIS DIRECTOR ____________________________________________________ Welcome, Colleagues! Welcome to the heady days of the British House of Commons! My name is Thadeus Obora, and I will be serving as your Crisis Director. I am a fourth-year student and a History/Political Science double major in the college, with a great love for all things Industrial Revolution and historical. I hail from Naperville, in the suburbs of Chicago (Neuqua Valley HS) and love the opportunity I have now to finally live in Chicago. As somebody who almost went to MUNUC when I was in high school, I relish the opportunity to participate in the behind-the-scenes antics that make this conference run well - so much so that after being an Assistant Chair on the Cuba 1960 committee my first year, Chair on the German Unification committee by second year, and the Japan 1960 committee last year, I have returned as an executive! When not frantically working on the background guide for this committee, I can be found exploring the city for new restaurants and foodie-locales, browsing eBay, or repairing vintage fountain pens and typewriters - an archaic hobby that I use to finance all of the binge-eating. -

Year 7 History Project

Year 7 History Project Middle Ages - Power and Protest Session 1: King Edward I • In the following slides you will find information relating to: • Edward and parliament • Edward and Wales • Edward and the War of Independence Edward I • Edward facts • Edward was born in 1239 • In 1264 Edward was held prisoner when English barons rebelled against his father Henry III. • In 1271 Edward joined a Christian Crusade to try and free Jerusalem from Muslim control • Edward took the throne in 1272. • Edward fought a long campaign to conquer Wales • Edward built lots of castles in Wales such as Caernarfon, Conwy and Harlech castles • Edward had two nicknames - 'Longshanks' because he was so tall and the 'Hammer of the Scots' for obvious reasons • Edward’s war with Scotland eventually brought about his death when he died from sickness in 1307 when marching towards the Scottish Border. Llywelyn Ap Gruffudd • In 1275 Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of Wales refused to pay homage (respect) to King Edward I of England as he believed himself ruler of Wales after fighting his own uncles for the right. • This sparked a war that would result in the end of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (the last) who was killed fighting the English in 1282 after several years of on off warfare. • Edward I destroyed the armies of Llywelyn when they revolted against England trying to take complete control of Wales. • As a result Llywelyn is known as the last native ruler of Wales. • After his death Edward I took his head from his body and placed it on a spike in London to deter future revolts. -

The Medieval Parliament

THE MEDIEVAL PARLIAMENT General 4006. Allen, John. "History of the English legislature." Edinburgh Review 35 (March-July 1821): 1-43. [Attributed in the Wellesley Index; a review of the "Reports on the Dignity of a Peer".] 4007. Arnold, Morris S. "Statutes as judgments: the natural law theory of parliamentary activities in medieval England." University of Pennsylvania Law Review 126 (1977-78): 329-43. 4008. Barraclough, G. "Law and legislation in medieval England." Law Quarterly Review 56 (1940): 75-92. 4009. Bemont, Charles. "La séparation du Parlement anglais en deux Chambres." In Actes du premier Congrès National des Historiens Français. Paris 20-23 Avril 1927, edited by Comite Français des Sciences Historiques: 33-35. Paris: Éditions Rieder, 1928. 4010. Betham, William. Dignities, feudal and parliamentary, and the constitutional legislature of the United Kingdom: the nature and functions of the Aula Regis, the Magna Concilia and the Communa Concilia of England, and the history of the parliaments of France, England, Scotland, and Ireland, investigated and considered with a view to ascertain the origin, progress, and final establishment of legislative parliaments, and the dignity of a peer, or Lord of Parliament. London: Thomas and William Boone, 1830. xx, 379p. [A study of the early history of the Parliaments of England, Ireland and Scotland, with special emphasis on the peerage; Vol. I only published.] 4011. Bodet, Gerald P. Early English parliaments: high courts, royal councils, or representative assemblies? Problems in European civilization. Boston, Mass.: Heath, 1967. xx,107p. [A collection of extracts from leading historians.] 4012. Boutmy, E. "La formation du Parlement en Angleterre." Revue des Deux Mondes 68 (March-April 1885): 82-126. -

A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G3

Factsheet G3 House of Commons Information Office General Series A Brief Chronology of the August 2010 House of Commons Contents Origins of Parliament at Westminster: Before 1400 2 15th and 16th centuries 3 Treason, revolution and the Bill of Rights: This factsheet has been archived so the content The 17th Century 4 The Act of Settlement to the Great Reform and web links may be out of date. Please visit Bill: 1700-1832 7 our About Parliament pages for current Developments to 1945 9 information. The post-war years: 11 The House of Commons in the 21st Century 13 Contact information 16 Feedback form 17 The following is a selective list of some of the important dates in the history of the development of the House of Commons. Entries marked with a “B” refer to the building only. This Factsheet is also available on the Internet from: http://www.parliament.uk/factsheets August 2010 FS No.G3 Ed 3.3 ISSN 0144-4689 © Parliamentary Copyright (House of Commons) 2010 May be reproduced for purposes of private study or research without permission. Reproduction for sale or other commercial purposes not permitted. 2 A Brief Chronology of the House of Commons House of Commons Information Office Factsheet G3 Origins of Parliament at Westminster: Before 1400 1097-99 B Westminster Hall built (William Rufus). 1215 Magna Carta sealed by King John at Runnymede. 1254 Sheriffs of counties instructed to send Knights of the Shire to advise the King on finance. 1265 Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, summoned a Parliament in the King’s name to meet at Westminster (20 January to 20 March); it is composed of Bishops, Abbots, Peers, Knights of the Shire and Town Burgesses. -

Schuler Dissertation Final Document

COUNSEL, POLITICAL RHETORIC, AND THE CHRONICLE HISTORY PLAY: REPRESENTING COUNCILIAR RULE, 1588-1603 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anne-Marie E. Schuler, B.M., M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Dutton, Advisor Professor Luke Wilson Professor Alan B. Farmer Professor Jennifer Higginbotham Copyright by Anne-Marie E. Schuler 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation advances an account of how the genre of the chronicle history play enacts conciliar rule, by reflecting Renaissance models of counsel that predominated in Tudor political theory. As the texts of Renaissance political theorists and pamphleteers demonstrate, writers did not believe that kings and queens ruled by themselves, but that counsel was required to ensure that the monarch ruled virtuously and kept ties to the actual conditions of the people. Yet, within these writings, counsel was not a singular concept, and the work of historians such as John Guy, Patrick Collinson, and Ann McLaren shows that “counsel” referred to numerous paradigms and traditions. These theories of counsel were influenced by a variety of intellectual movements including humanist-classical formulations of monarchy, constitutionalism, and constructions of a “mixed monarchy” or a corporate body politic. Because the rhetoric of counsel was embedded in the language that men and women used to discuss politics, I argue that the plays perform a kind of cultural work, usually reserved for literature, that reflects, heightens, and critiques political life and the issues surrounding conceptions of conciliar rule.