Japonism in Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

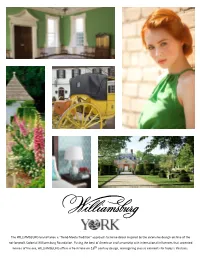

The WILLIAMSBURG Brand Takes a “Trend-Meets-Tradition” Approach

The WILLIAMSBURG brand takes a “Trend-Meets-Tradition” approach to home décor inspired by the extensive design archive of the not-for-profit Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Fusing the best of American craftsmanship with international influences that accented homes of the era, WILLIAMSBURG offers a fresh take on 18th-century design, reimagining classic elements for today’s lifestyles. GARDEN IMAGES Highlighted by a magnificent watercolor painted by Georg Ehret in 1737, this botanical design captures the natural ambience of gardens in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area. The large magnolia blossoms, flowering dogwood, and occasional butterfly are shown in multiple colors on a lightly textured field which mimics fine linen or, in one instance, cloth of gold. Six variations include cream ground with green, blue, and beige, brown ground with deep pinks and blue-greens, a charcoal ground with purples and ochres. There is also a distinctive metallic gold ground enhanced by plum accents. Dickinson Trellis or Amelia Stripe would make a handsome partner. TAUNTON TEXTURE During the 18th- century, Taunton, England, was a center for the manufacture of woolen broadcloth. This wall paper, named for that city, bears a similarity. The textured background looks like woven cloth, while vertical and horizontal faux slubs mimic the appearance and feel of earlier fabrics made from nubby hand-spun yarns. This pattern, in five palettes including beige with taupe and white, or light and medium grey with cream, offers a subtle complement to many other designs in the WILLIAMSBURG collection. For example, use with Dinwiddie Damask or with John Rocque’s London Map, circa 1740s, Mural. -

Mothership.SG

Search Search Go S’porean Harvard scholar & equity fund associate takes to Tokyo streets as Japan’s 1st foreign oiran The most elegant performer there, if we do say so ourselves. By Yeo Kaiqi | 22 hours 184 Here’s something cool that you might not have heard about that happened late last month. While all of us were busy getting mad about the presidential (s)election, Singaporean Rachel Leng was getting out there and making a name for us in a pretty interesting way. According to The Japan News, one of Japan’s five national newspapers, the 27-year-old was selected to perform as one of five oiran of the annual Shinagawa Shukuba Matsuri festival, an annual cultural event held in Tokyo, Japan. Here she is, second from the left: Photo via Rachel Leng’s Facebook post Advertisement You can see her walking elegantly down the street in super high wooden platform clogs here. In this video in particular, she demonstrates a distinctive style called “soto hachimonji”, in which the walker’s feet trace a sideways arc on the ground: But first, what’s an oiran, and what’s this festival? An oiran is a Japanese prostitute who was very popular and highly regarded mostly for her beauty — not to be confused with the better-known term geisha, who is very skilled in song, dance, playing an instrument, and otherwise entertaining guests. Leng appears in the “Oiran Dochu”, one of the main attractions of the Shinagawa Shukuba Matsuri, which celebrates the history of Shinagawa during the Edo period and its role in making Tokyo the city it is today, by re- creating the din and bustle of the Shinagawa ward back then. -

Estudo E Desenvolvimento Do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA E MATEMÁTICA APLICADA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO MESTRADO ACADÊMICO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO Aprendizagem da Língua Japonesa Apoiada por Ferramentas Computacionais: Estudo e Desenvolvimento do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders Juvane Nunes Marciano Natal-RN Fevereiro de 2014 Juvane Nunes Marciano Aprendizagem da Língua Japonesa Apoiada por Ferramentas Computacionais: Estudo e Desenvolvimento do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders Dissertação de Mestrado apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemas e Computação do Departamento de Informática e Matemática Aplicada da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte como requisito final para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Sistemas e Computação. Linha de pesquisa: Engenharia de Software Orientador Prof. Dr. Leonardo Cunha de Miranda PPGSC – PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO DIMAP – DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA E MATEMÁTICA APLICADA CCET – CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA UFRN – UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE Natal-RN Fevereiro de 2014 UFRN / Biblioteca Central Zila Mamede Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte Marciano, Juvane Nunes. Aprendizagem da língua japonesa apoiada por ferramentas computacionais: estudo e desenvolvimento do jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders. / Juvane Nunes Marciano. – Natal, RN, 2014. 140 f.: il. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Leonardo Cunha de Miranda. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Centro de Ciências Exatas e da Terra. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemas e Computação. 1. Informática na educação – Dissertação. 2. Interação humano- computador - Dissertação. 3. Jogo educacional - Dissertação. 4. Kanas – Dissertação. 5. Hiragana – Dissertação. 6. Roma-ji – Dissertação. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Dame Ellen Terry GBE

Dame Ellen Terry GBE Key Features • Born Alice Ellen Terry 27 February 1847, in Market Street, Coventry • Married George Frederic Watts, artist 20 February 1864 in Kensington. Separated 1864. Divorced 13 March 1877 • Eloped with Edward William Godwin, architect in 1868 with whom she had two children – Edith (b1869) and Edward Gordon (b1872). Godwin left Ellen in early 1875. • Married Charles Kelly, actor 21 November 1877 in Kensington. Separated 1881. Marriage ended by Kelly’s death on 17 April 1885. • Married James Carew, actor 22 March 1907 in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA. Unofficially separated 1909. • Died 21 July 1928 Smallhythe Place. Funeral service at Smallhythe church. Cremation at Golders Green Crematorium, London. Ashes placed in St Paul’s Covent Garden (the actors’ church). Urn on display on south wall (east end). A brief marital history Ellen Terry married three times and, between husbands one and two, eloped with the man who Ellen Terry’s first marriage was to the artist G F Watts. She was a week shy of 17 years old, young and exuberant, and he was a very neurotic and elderly 46. They were totally mismatched. Within a year he had sent her back to her family but would not divorce her. When she was 21, Ellen Terry eloped with the widower Edward Godwin and, as a consequence, was estranged from her family. Ellen said he was the only man she really loved. They had two illegitimate children, Edith and Edward. The relationship foundered after 6 or 7 years when they were overcome by financial problems resulting from over- expenditure on the house that Godwin had designed and built for them in Harpenden. -

Paul Iribe (1883–1935) Was Born in Angoulême, France

4/11/2019 Bloomsbury Fashion Central - BLOOMSBURY~ Sign In: University of North Texas Personal FASHION CENTRAL ~ No Account? Sign Up About Browse Timelines Store Search Databases Advanced search --------The Berg Companion to Fashion eBook Valerie Steele (ed) Berg Fashion Library IRIBE, PAUL Michelle Tolini Finamore Pages: 429–430 Paul Iribe (1883–1935) was born in Angoulême, France. He started his career in illustration and design as a newspaper typographer and magazine illustrator at numerous Parisian journals and daily papers, including Le temps and Le rire. In 1906 Iribe collaborated with a number of avantgarde artists to create the satirical journal Le témoin, and his illustrations in this journal attracted the attention of the fashion designer Paul Poiret. Poiret commissioned Iribe to illustrate his first major dress collection in a 1908 portfolio entitled Les robes de Paul Poiret racontées par Paul Iribe . This limited edition publication (250 copies) was innovative in its use of vivid fauvist colors and the simplified lines and flattened planes of Japanese prints. To create the plates, Iribe utilized a hand coloring process called pochoir, in which bronze or zinc stencils are used to build up layers of color gradually. This publication, and others that followed, anticipated a revival of the fashion plate in a modernist style to reflect a newer, more streamlined fashionable silhouette. In 1911 the couturier Jeanne Paquin also hired Iribe , along with the illustrators Georges Lepape and Georges Barbier, to create a similar portfolio of her designs, entitled L’Eventail et la fourrure chez Paquin. Throughout the 1910s Iribe became further involved in fashion and added design for theater, interiors, and jewelry to his repertoire. -

The Sexual Life of Japan : Being an Exhaustive Study of the Nightless City Or the "History of the Yoshiwara Yūkwaku"

Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924012541797 Cornell University Library HQ 247.T6D27 1905 *erng an exhau The sexual life of Japan 3 1924 012 541 797 THE SEXUAL LIFE OF JAPAN THE SEXUAL LIFE OF JAPAN BEING AN EXHAUSTIVE STUDY OF THE NIGHTLESS CITY 1^ ^ m Or the "HISTORY of THE YOSHIWARA YUKWAKU " By J, E. DE BECKER "virtuous men hiive siitd, both in poetry and ulasslo works, that houses of debauch, for women of pleasure and for atreet- walkers, are the worm- eaten spots of cities and towns. But these are necessary evils, and If they be forcibly abolished, men of un- righteous principles will become like ravelled thread." 73rd section of the " Legacy of Ityasu," (the first 'I'okugawa ShOgun) DSitl) Niimrraiia SUuatratiuna Privately Printed . Contents PAGE History of the Yosliiwara Yukwaku 1 Nilion-dzutsumi ( 7%e Dyke of Japan) 15 Mi-kaeri Yanagi [Oazing back WUlow-tree) 16 Yosliiwara Jiuja ( Yoahiwara Shrine) 17 The "Aisome-zakura " {Chen-y-tree of First Meeting) 18 The " Koma-tsunagi-matsu " {Colt tethering Pine-tree) 18 The " Ryojin no Ido " {Traveller's Well) 18 Governmeut Edict-board and Regulations at the Omen (Great Gate) . 18 The Present Omon 19 »Of the Reasons why going to the Yosliiwara was called " Oho ve Yukn " ". 21 Classes of Brothels 21 Hikite-jaya (" Introducing Tea-houses"') 28 The Ju-hachi-ken-jaya (^Eighteen Tea-houses) 41 The " Amigasa-jaya -

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour a Practice

The Male Fashion Bias Mr. Mark Neighbour A Practice-Led Masters by Research Degree Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Discipline: Fashion Year of Submission: 2008 Key Words Male fashion Clothing design Gender Tailoring Clothing construction Dress reform Innovation Design process Contemporary menswear Fashion exhibition - 2 - Abstract Since the establishment of the first European fashion houses in the nineteenth century the male wardrobe has been continually appropriated by the fashion industry to the extent that every masculine garment has made its appearance in the female wardrobe. For the womenswear designer, menswear’s generic shapes are easily refitted and restyled to suit the prevailing fashionable silhouette. This, combined with a wealth of design detail and historical references, provides the cyclical female fashion system with an endless supply of “regular novelty” (Barthes, 2006, p.68). Yet, despite the wealth of inspiration and technique across both male and female clothing, the bias has largely been against menswear, with limited reciprocal benefit. Through an exploration of these concepts I propose to answer the question; how can I use womenswear patternmaking and construction technique to implement change in menswear design? - 3 - Statement of Original Authorship The work contained in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma at any other higher educational institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Signed: Mark L Neighbour Dated: - 4 - Acknowledgements I wish to thank and acknowledge everyone who supported and assisted this project. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

GI Journal No. 75 1 November 26, 2015

GI Journal No. 75 1 November 26, 2015 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO.75 NOVEMBER 26, 2015 / AGRAHAYANA 05, SAKA 1936 GI Journal No. 75 2 November 26, 2015 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 6 4 GI Applications Bagh Prints of Madhya Pradesh (Logo )- GI Application No.505 7 Sankheda Furniture (Logo) - GI Application No.507 19 Kutch Embroidery (Logo) - GI Application No.509 26 Karnataka Bronzeware (Logo) - GI Application No.510 35 Ganjifa Cards of Mysore (Logo) - GI Application No.511 43 Navalgund Durries (Logo) - GI Application No.512 49 Thanjavur Art Plate (Logo) - GI Application No.513 57 Swamimalai Bronze Icons (Logo) - GI Application No.514 66 Temple Jewellery of Nagercoil (Logo) - GI Application No.515 75 5 GI Authorised User Applications Patan Patola – GI Application No. 232 80 6 General Information 81 7 Registration Process 83 GI Journal No. 75 3 November 26, 2015 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 75 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 26th November 2015 / Agrahayana 05th, Saka 1936 has been made available to the public from 26th November 2015. GI Journal No. 75 4 November 26, 2015 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 530 Tulaipanji Rice 31 Agricultural 531 Gobindobhog Rice 31 Agricultural 532 Mysore Silk 24, 25 and 26 Handicraft 533 Banglar Rasogolla 30 Food Stuffs 534 Lamphun Brocade Thai Silk 24 Textiles GI Journal No. -

Jeanne Lanvin

JEANNE LANVIN A 01long history of success: the If one glances behind the imposing façade of Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, 22, in Paris, Lanvin fashion house is the oldest one will see a world full of history. For this is the Lanvin headquarters, the oldest couture in the world. The first creations house in the world. Founded by Jeanne Lanvin, who at the outset of her career could not by the later haute couture salon even afford to buy fabric for her creations. were simple clothes for children. Lanvin’s first contact with fashion came early in life—admittedly less out of creative passion than economic hardship. In order to help support her six younger siblings, Lanvin, then only fifteen, took a job with a tailor in the suburbs of Paris. In 1890, at twenty-seven, Lanvin took the daring leap into independence, though on a modest scale. Not far from the splendid head office of today, she rented two rooms in which, for lack of fabric, she at first made only hats. Since the severe children’s fashions of the turn of the century did not appeal to her, she tailored the clothing for her young daughter Marguerite herself: tunic dresses designed for easy movement (without tight corsets or starched collars) in colorful patterned cotton fabrics, generally adorned with elaborate smocking. The gentle Marguerite, later known as Marie-Blanche, was to become the Salon Lanvin’s first model. When walking JEANNE LANVIN on the street, other mothers asked Lanvin and her daughter from where the colorful loose dresses came. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933).