Inflation in the Reconstruction of Poland 1918-1927

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth As a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity*

Chapter 8 The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity* Satoshi Koyama Introduction The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was one of the largest states in early modern Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century, after the union of Lublin (1569), the Polish-Lithuanian state covered an area of 815,000 square kilometres. It attained its greatest extent (990,000 square kilometres) in the first half of the seventeenth century. On the European continent there were only two larger countries than Poland-Lithuania: the Grand Duchy of Moscow (c.5,400,000 square kilometres) and the European territories of the Ottoman Empire (840,000 square kilometres). Therefore the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Latin-Christian Europe in the early modern period (Wyczański 1973: 17–8). In this paper I discuss the internal diversity of the Commonwealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and consider how such a huge territorial complex was politically organised and integrated. * This paper is a part of the results of the research which is grant-aided by the ‘Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research’ program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2005–2007. - 137 - SATOSHI KOYAMA 1. The Internal Diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Poland-Lithuania before the union of Lublin was a typical example of a composite monarchy in early modern Europe. ‘Composite state’ is the term used by H. G. Koenigsberger, who argued that most states in early modern Europe had been ‘composite states, including more than one country under the sovereignty of one ruler’ (Koenigsberger, 1978: 202). -

Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics After World War I

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER June 2018 Working Paper 2018-06 https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2018/06/ Suggested citation: Lopez, Jose A., Kris James Mitchener. 2018. “Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2018-06. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2018-06 The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER* May 9, 2018 ABSTRACT. Fiscal deficits, elevated debt-to-GDP ratios, and high inflation rates suggest hyperinflation could have potentially emerged in many European countries after World War I. We demonstrate that economic policy uncertainty was instrumental in pushing a subset of European countries into hyperinflation shortly after the end of the war. Germany, Austria, Poland, and Hungary (GAPH) suffered from frequent uncertainty shocks – and correspondingly high levels of uncertainty – caused by protracted political negotiations over reparations payments, the apportionment of the Austro-Hungarian debt, and border disputes. In contrast, other European countries exhibited lower levels of measured uncertainty between 1919 and 1925, allowing them more capacity with which to implement credible commitments to their fiscal and monetary policies. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

The Great Divergence the Princeton Economic History

THE GREAT DIVERGENCE THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD Joel Mokyr, Editor Growth in a Traditional Society: The French Countryside, 1450–1815, by Philip T. Hoffman The Vanishing Irish: Households, Migration, and the Rural Economy in Ireland, 1850–1914, by Timothy W. Guinnane Black ’47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy, and Memory, by Cormac k Gráda The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy, by Kenneth Pomeranz THE GREAT DIVERGENCE CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY Kenneth Pomeranz PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD COPYRIGHT 2000 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 3 MARKET PLACE, WOODSTOCK, OXFORDSHIRE OX20 1SY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA POMERANZ, KENNETH THE GREAT DIVERGENCE : CHINA, EUROPE, AND THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD ECONOMY / KENNETH POMERANZ. P. CM. — (THE PRINCETON ECONOMIC HISTORY OF THE WESTERN WORLD) INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX. ISBN 0-691-00543-5 (CL : ALK. PAPER) 1. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—18TH CENTURY. 2. EUROPE—ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—19TH CENTURY. 3. CHINA— ECONOMIC CONDITIONS—1644–1912. 4. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT—HISTORY. 5. COMPARATIVE ECONOMICS. I. TITLE. II. SERIES. HC240.P5965 2000 337—DC21 99-27681 THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN TIMES ROMAN THE PAPER USED IN THIS PUBLICATION MEETS THE MINIMUM REQUIREMENTS OF ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) (PERMANENCE OF PAPER) WWW.PUP.PRINCETON.EDU PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 3579108642 Disclaimer: Some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. -

On the Classification of Economic Fluctuations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Explorations in Economic Research, Volume 2, number 2 Volume Author/Editor: NBER Volume Publisher: NBER Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/moor75-2 Publication Date: 1975 Chapter Title: On the Classification of Economic Fluctuations Chapter Author: John R. Meyer, Daniel H. Weinberg Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c7408 Chapter pages in book: (p. 43 - 78) Moo5 2 'fl the 'if at fir JOHN R. MEYER National Bureau of Economic on, Research and Harvard (Jriiversity drawfi 'Ces DANIEL H. WEINBERG National Bureau of Economic iliOns Research and'ale University 'Clical Ihit onth Economic orith On the Classification of 1975 0 Fluctuations and ABSTRACT:Attempts to classify economic fluctuations havehistori- cally focused mainly on the identification of turning points,that is, so-called peaks and troughs. In this paper we report on anexperimen- tal use of multivariate discriminant analysis to determine afour-phase classification of the business cycle, using quarterly andmonthly U.S. economic data for 1947-1973. Specifically, weattempted to discrimi- nate between phases of (1) recession, (2) recovery, (3)demand-pull, and (4) stagflation. Using these techniques, we wereable to identify two complete four-phase cycles in the p'stwarperiod: 1949 through 1953 and 1960 through 1969. ¶ As a furher test,extrapolations were made to periods occurring before February 1947 andalter September 1973. Using annual data for the period 1926 -1951, a"backcasting" to the prewar U.S. economy suggests that the n.ajordifference between prewar and postwar business cycles isthe onii:sion of the stagflation phase in the former. -

The Global Financial Crisis: Is It Unprecedented?

Conference on Global Economic Crisis: Impacts, Transmission, and Recovery Paper Number 1 The Global Financial Crisis: Is It Unprecedented? Michael D. Bordo Professor of Economics, Rutgers University, and National Bureau of Economic Research and John S. Landon-Lane Associate Professor of Economics, Rutgers University 1. Introduction A financial crisis in the US in 2007 spread to Europe and led to a recession across the world in 2007-2009. Have we seen patterns like this before or is the recent experience novel? This paper compares the recent crisis and recent recession to earlier international financial crises and global recessions. First we review the dimensions of the recent crisis. We then present some historical narrative on earlier global crises in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The description of earlier global crises leads to a sense of déjà vu. We next demarcate several chronologies of the incidence of various kinds of crises: banking, currency and debt crises and combinations of them across a large number of countries for the period from 1880 to 2010. These chronologies come from earlier work of Bordo with Barry Eichengreen, Daniela Klingebiel and Maria Soledad Martinez-Peria and with Chris Meissner (Bordo et al (2001), Bordo and Meissner ( 2007)) , from Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s recent book (2009) and studies by the IMF (Laeven and Valencia 2009,2010).1 Based on these chronologies we look for clusters of crisis events which occur in a number of countries and across continents. These we label global financial crises. 1 There is considerable overlap in the different chronologies as Reinhart and Rogoff incorporated many of our dates and my coauthors and I used IMF and World Bank chronologies for the period since the early 1970s. -

Firearms and Artillery in Jan Długosz's Annales Seu Cronicae Incliti Regni Poloniae

FASCICULI ARCHAEOLOGIAE HISTORICAE FASC. XXV, PL ISSN 0860-0007 JAN SZYMCZAK FIREARMS AND ARTILLERY IN JAN DŁUGOSZ’S ANNALES SEU CRONICAE INCLITI REGNI POLONIAE Jan Długosz (Johannes Dlugossius), whose 600th birth- and a metal arrow being thrown from its barrel. Another day anniversary will be celebrated in 2015, is counted handwritten copy by Walter de Milimete, entitled De secre- among the greatest chroniclers of fifteenth-century Europe. tis secretorum, containing a figure representing a similarly As the present volume of „Fasciculi Archaeologiae His- shaped cannon surrounded by four gunners, is held at the toricate” is devoted to the issue of firearms and artillery, British Museum in London. I would like to come back to the remarks on this question As far as battlefield activities are concerned, the year made by undoubtedly the most outstanding Polish annalist 1331, when cannons were used during the siege of Civi- in his largest work entitled „Annales seu Cronicae incliti dale del Friuli in northern Italy, deserves special attention. Regni Poloniae”1. The use of cannons was also mentioned during sieges in *** France and England throughout 1338, as well as in Spain It is a well known fact that in the case of firearms and in 1342. Cannons were recorded in the municipal accounts heavy guns, projectiles are launched due to a propelling of Aachen, Germany, in 1346. In the same year, pieces force generated by the combustion of gunpowder (originally of artillery were first used in open battle at Crécy. Those only black powder was used for this purpose). This propel- were the beginnings of artillery in Europe. -

An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church Under Communism Kathryn Burns Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 More Catholic than the Pope: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism Kathryn Burns Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Burns, Kathryn, "More Catholic than the Pope: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism" (2013). Honors Theses. 638. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/638 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “More Catholic than the Pope”: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism By Kathryn Burns ******************** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June 2013 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………..........................................1 Chapter I. The Roman Catholic Church‟s Influence in Poland Prior to World War II…………………………………………………………………………………………………...4 Chapter II. World War II and the Rise of Communism……………….........................................38 Chapter III. The Decline and Demise of Communist Power……………….. …………………..63 Chapter IV. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….76 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..78 ii Abstract Poland is home to arguably the most loyal and devout Catholics in Europe. A brief examination of the country‟s history indicates that Polish society has been subjected to a variety of politically, religiously, and socially oppressive forces that have continually tested the strength of allegiance to the Catholic Church. -

Trianon 1920–2020 Some Aspects of the Hungarian Peace Treaty of 1920

Trianon 1920–2020 Some Aspects of the Hungarian Peace Treaty of 1920 TRIANON 1920–2020 SOME ASPECTS OF THE HUNGARIAN PEACE TREATY OF 1920 Edited by Róbert Barta – Róbert Kerepeszki – Krzysztof Kania in co-operation with Ádám Novák Debrecen, 2021 Published by The Debreceni Universitas Nonprofit Közhasznú Kft. and the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Department of History Refereed by Levente Püski Proofs read by Máté Barta Desktop editing, layout and cover design by Zoltán Véber Járom Kulturális Egyesület A könyv megjelenését a Nemzeti Kulturális Alap támomgatta. The publish of the book is supported by The National Cultural Fund of Hungary ISBN 978-963-490-129-9 © University of Debrecen, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Department of History, 2021 © Debreceni Universitas Nonprofit Közhasznú Kft., 2021 © The Authors, 2021 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Printed by Printart-Press Kft., Debrecen Managing Director: Balázs Szabó Cover design: A contemporary map of Europe after the Great War CONTENTS Foreword and Acknowledgements (RÓBERT BARTA) ..................................7 TRIANON AND THE POST WWI INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS MANFRED JATZLAUK, Deutschland und der Versailler Friedensvertrag von 1919 .......................................................................................................13 -

How History Matters for Student Performance. Lessons from the Partitions of Poland Ú Job Market Paper Latest Version: HERE

How History Matters for Student Performance. Lessons from the Partitions of Poland ú Job Market Paper Latest Version: HERE. Pawe≥Bukowski † This paper examines the effect on current student performance of the 19th century Partitions of Poland among Austria, Prussia and Russia. Despite the modern similarities of the three regions, using a regression discontinuity design I show that student test scores are 0.6 standard deviation higher on the Austrian side of the former Austrian-Russian border. This magnitude is comparable to the black vs. white test score gap in the US. On the other hand, I do not find evidence for differences on the Prussian-Russian border. Using a theoretical model and indirect evidence I argue that the Partitions have persisted through their impact on social norms toward local schools. Nevertheless, the persistent effect of Austria is puzzling given the histori- cal similarities of the Austrian and Prussian educational systems. I argue that the differential legacy of Austria and Prussia originates from the Aus- trian Empire’s policy to promote Polish identity in schools and the Prussian Empire’s efforts to Germanize the Poles through education. JEL Classification: N30, I20, O15, J24 úI thank Sascha O. Becker, Volha Charnysh, Gregory Clark, Tomas Cvrcek, John S. Earle, Irena Grosfeld, Hedvig Horvát, Gábor Kézdi, Jacek Kochanowicz, Attila Lindner, Christina Romer, Ruth M. Schüler, Tamás Vonyó, Jacob Weisdorf, Agnieszka WysokiÒska, Noam Yuchtman, the partici- pants of seminars at Central European University, University of California at Berkeley, University of California at Davis, Warsaw School of Economics, Ifo Center for the Economics of Education and FRESH workshops in Warsaw and Canterbury, WEast workshop in Belgrade, European Historical Economics Society Summer School in Berlin for their comments and suggestions. -

The Grunwald Trail

n the Grunwald fi elds thousands of soldiers stand opposite each other. Hidden below the protec- tive shield of their armour, under AN INVITATION Obanners waving in the wind, they hold for an excursion along long lances. Horses impatiently tear their bridles and rattle their hooves. Soon the the Grunwald Trail iron regiments will pounce at each other, to clash in a deadly battle And so it hap- pens every year, at the same site knights from almost the whole of Europe meet, reconstructing events which happened over six hundred years ago. It is here, on the fi elds between Grunwald, Stębark and Łodwigowo, where one of the biggest battles of Medieval Europe took place on July . The Polish and Lithuanian- Russian army, led by king Władysław Jagiełło, crushed the forces of the Teutonic Knights. On the battlefi eld, knights of the order were killed, together with their chief – the great Master Ulrich von Jungingen. The Battle of Grunwald, a triumph of Polish and Lithuanian weapons, had become the symbol of power of the common monarchy. When fortune abandoned Poland and the country was torn apart by the invaders, reminiscence of the battle became the inspiration for generations remembering the past glory and the fi ght for national independence. Even now this date is known to almost every Pole, and the annual re- enactment of the battle enjoys great popularity and attracts thousands of spectators. In Stębark not only the museum and the battlefi eld are worth visiting but it is also worthwhile heading towards other places related to the great battle with the Teutonic Knights order. -

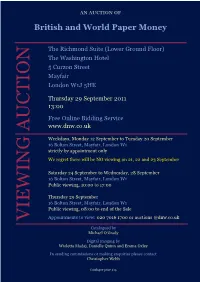

A Uct Ion View

AN AUCTION OF British and World Paper Money The Richmond Suite (Lower Ground Floor) The Washington Hotel 5 Curzon Street Mayfair London W1J 5HE Thursday 29 September 2011 13:00 Free Online Bidding Service www.dnw.co.uk AUCTION Weekdays, Monday 12 September to Tuesday 20 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 strictly by appointment only We regret there will be NO viewing on 21, 22 and 23 September Saturday 24 September to Wednesday, 28 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 10:00 to 17:00 Thursday 29 September 16 Bolton Street, Mayfair, London W1 Public viewing, 08:00 to end of the Sale Appointments to view: 020 7016 1700 or auctions @dnw.co.uk VIEWING Catalogued by Michael O’Grady Digital Imaging by Wioletta Madaj, Danielle Quinn and Emma Oxley In sending commissions or making enquiries please contact Christopher Webb Catalogue price £15 C ONTENTS Please note: Lots will be sold at a rate of approximately 150 per hour The Sale will be held in one Session starting at 13.00 A Collection of Treasury Notes, the Property of a Gentleman (Part II) ...................................4001-4035 The Celebrated Million Pound Note .........................................................................4036 A Presentation Album to John Benjamin Heath ................................................................................4037 British Banknotes from other properties ..................................................................................4038-4120 The Peter Stanton Collection of Paper Money of Guernsey