The Low Countries. Jaargang 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flemish Cinema and Film Culture Through South African Eyes

Flemish Cinema and Film Culture through South African Eyes By Martin P. Botha Fall 2007 Issue of KINEMA THE HERITAGE OF FILM: PERSPECTIVE ON FLEMISH CINEMA AND FILM CUL- TURE THROUGH SOUTH AFRICAN EYES I assisted the Locarno Film festival in 2005 with a retrospective of short films by young South African directors. There I met a very talented, young Flemish director, whose film was by far the best in the one section.(1) It moved me immensely with its honest portrait of alienation and racial discrimination. We had a long discussion on film history, aesthetics and film cultures. We also talked about the historyof film in Belgium and it was noted that while the French speaking side of Belgian cinema had recently received international acclaim (for example, the work by the Dardenne Brothers), Flemish cinema was struggling. In fact, the young filmmaker made the statement that there was little to be excited about in the historyof Flemish cinema. He felt especially that the films about rural communities and most of the historical dramas were not saying much about contemporary Flanders, in particular, the youth. I have heard this argument before, but in a totally different cultural context. Many young, aspiring South African filmmakers have told me there is very little in South African film history which makes themproud of their film culture. For decades South African film culture has been in isolation. The years 1959to1980 were characterised by an artistic revival in filmmaking throughout the world, ranging from exciting political films in Africa and Latin America to examples of great art cinema in Europe and Asia. -

Gary Schwartz

Gary Schwartz A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings as a Test Case for Connoisseurship Seldom has an exercise in connoisseurship had more going for it than the world-famous Rembrandt Research Project, the RRP. This group of connoisseurs set out in 1968 to establish a corpus of Rembrandt paintings in which doubt concer- ning attributions to the master was to be reduced to a minimum. In the present enquiry, I examine the main lessons that can be learned about connoisseurship in general from the first three volumes of the project. My remarks are limited to two central issues: the methodology of the RRP and its concept of authorship. Concerning methodology,I arrive at the conclusion that the persistent appli- cation of classical connoisseurship by the RRP, attended by a look at scientific examination techniques, shows that connoisseurship, while opening our eyes to some features of a work of art, closes them to others, at the risk of generating false impressions and incorrect judgments.As for the concept of authorship, I will show that the early RRP entertained an anachronistic and fatally puristic notion of what constitutes authorship in a Dutch painting of the seventeenth century,which skewed nearly all of its attributions. These negative judgments could lead one to blame the RRP for doing an inferior job. But they can also be read in another way. If the members of the RRP were no worse than other connoisseurs, then the failure of their enterprise shows that connoisseurship was unable to deliver the advertised goods. I subscribe to the latter conviction. This paper therefore ends with a proposal for the enrichment of Rembrandt studies after the age of connoisseurship. -

Openeclanewfieldinthehis- Work,Ret

-t horizonte Beitràge zu Kunst und Kunstwissenschaft horizons Essais sur I'art et sur son histoire orizzonti Saggi sull'arte e sulla storia dell'arte horizons Essays on Art and Art Research Hatje Cantz 50 Jahre Schweizerisches lnstitut flir Kunstwissenschaft 50 ans lnstitut suisse pour l'étude de I'art 50 anni lstituto svizzero di studi d'arte 50 Years Swiss lnstitute for Art Research Gary Schwartz The Clones Make the Master: Rembrandt in 1ó50 A high point brought low The year r65o was long considerecl a high point ot w-atershed fcrr Rem- a painr- orandt ls a painter. a date of qrear significance in his carecr' Of ng dated ,65o, n French auction catalogue of 18o6 writes: 'sa date prouve qu'il était dans sa plus grande force'" For John Smith, the com- pl.. of ih. firr, catalogue of the artistt paintings in r836, 165o was the golden age.' This convictíon surl ived well into zenith of Rembranclt's (It :]re tnentieth centufy. Ifl 1942, Tancred Borenius wfote: was about r65o one me-v sa)i that the characteristics of Rembrandt's final manner Rosenberg in r.rr e become cleady pronounced.'l 'This date,'wroteJakob cat. Paris, ro-rr r8o6 (l'ugt 'Rembrandt: life and wotk' (r9+8/ ry64),the standard texl on the master 1 Sale June t)).n\t.1o. Fr,,m thq sxns'6rjp1 rrl years, 'can be called the end of his middle period, or equallv Jt :,r many the entrv on thc painting i n the Corpns of this ''e11, the beginning of his late one.'a Bob Haak, in 1984, enriched Renbrandt paintings, r'ith thanks to the that of Rcmbrandt Research Project for show-ing ,r.rqe b1, contrasting Rembrandt's work aftet mid-centurl' with to me this and other sections of the draft 'Rembrandt not only kept his distance from the new -. -

Het Fenomeen “Poeske” Scherens

KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT LEUVEN FACULTEIT LETTEREN MASTER IN DE GESCHIEDENIS Het fenomeen “Poeske” Scherens Promotor Masterproef Prof. dr. D. VANYSACKER ingediend door HERPELINCK FRAN Leuven 2010-2011 Voorwoord Alsof hij soms even tot leven kwam, in een literaire wielerflits. Alsof hij soms even aan de einder voorbijvloog, in een welgemikte ‘kattensprong’. Jef “Poeske” Scherens is al even niet meer onder ons, maar zijn sportieve adem, evenals de ziel van zijn tijdsperiode, zijn vervat in honderden documenten, in archieven overal te lande, in privé-collecties, in oude kranten en tijdschriften. Het afgelopen jaar was er een van puzzelwerk. Puzzelstukjes vinden, was geen probleem. Punt was te kijken welk stukje het meest authentiek was. Vele stukjes blonken immers buitensporig fel. Jef “Poeske” Scherens was een overstijgende persoonlijkheid, die zowel op als naast de fiets wist te fascineren. Als sprintende baanwielrenner kende hij in de periode tussen de Twee Wereldoorlogen, het interbellum van de twintigste eeuw, veruit zijn gelijke niet. Scherens was als ‘fenomeen’ een ‘idool’, die supporters deed juichen, journalisten in de pen deed kruipen en lyrische reacties aan hen ontlokte. In een fervente poging op zoek te gaan naar een kern van waarheid en tijdsgevoel, was het vaak noodzakelijk mezelf te berispen, wanneer enthousiasme primeerde op kritische zin. Het leven van Jef Scherens rolt zich dan ook uit als een lofdicht, dat doorheen de jaren haast niet aan charme heeft ingeboet. Na een intensieve kennismaking met “Poeske”, wielerheld en volksfiguur, was ik anderzijds terdege verwonderd . De laatste decennia kenden wielerbelangstelling en ‘koersliteratuur’ een enorme hausse . Kronieken, biografieën en poëtische werken worden gekleurd door noeste renners en wervelende persoonlijkheden - al kan er sprake zijn van een chronologische en pragmatische richtlijn. -

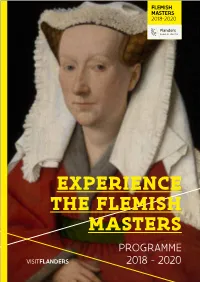

Experience the Flemish Masters Programme 2018 - 2020

EXPERIENCE THE FLEMISH MASTERS PROGRAMME 2018 - 2020 1 The contents of this brochure may be subject to change. For up-to-date information: check www.visitflanders.com/flemishmasters. 2 THE FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 AT THE PINNACLE OF ARTISTIC INVENTION FROM THE MIDDLE AGES ONWARDS, FLANDERS WAS THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE FAMOUS ART MOVEMENTS OF THE TIME: PRIMITIVE, RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE. FOR A PERIOD OF SOME 250 YEARS, IT WAS THE PLACE TO MEET AND EXPERIENCE SOME OF THE MOST ADMIRED ARTISTS IN WESTERN EUROPE. THREE PRACTITIONERS IN PARTICULAR, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL AND RUBENS ROSE TO PROMINENCE DURING THIS TIME AND CEMENTED THEIR PLACE IN THE PANTHEON OF ALL-TIME GREATEST MASTERS. 3 FLANDERS WAS THEN A MELTING POT OF ART AND CREATIVITY, SCIENCE AND INVENTION, AND STILL TODAY IS A REGION THAT BUSTLES WITH VITALITY AND INNOVATION. The “Flemish Masters” project has THE FLEMISH MASTERS been established for the inquisitive PROJECT 2018-2020 traveller who enjoys learning about others as much as about him or The Flemish Masters project focuses Significant infrastructure herself. It is intended for those on the life and legacies of van Eyck, investments in tourism and culture who, like the Flemish Masters in Bruegel and Rubens active during are being made throughout their time, are looking to immerse th th th the 15 , 16 and 17 centuries, as well Flanders in order to deliver an themselves in new cultures and new as many other notable artists of the optimal visitor experience. In insights. time. addition, a programme of high- quality events and exhibitions From 2018 through to 2020, Many of the works by these original with international appeal will be VISITFLANDERS is hosting an Flemish Masters can be admired all organised throughout 2018, 2019 abundance of activities and events over the world but there is no doubt and 2020. -

Cultural Branding in the Early Modern Period 31 the Literary Author Lieke Van Deinsen and Nina Geerdink

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/handle/2066/232945 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-24 and may be subject to change. Joosten & Steenmeijer(eds) Dera, den Braber, Van Branding Books Across the Ages Strategies and Key Concepts in Literary Branding Branding Books Across the Ages Across the Books Branding Edited by Helleke van den Braber, Jeroen Dera, Jos Joosten and Maarten Steenmeijer Branding Books Across the Ages Branding Books Across the Ages Strategies and Key Concepts in Literary Branding Edited by Helleke van den Braber, Jeroen Dera, Jos Joosten, and Maarten Steenmeijer Amsterdam University Press This volume is supported by the Stichting Frederik Muller Fonds, the Paul Hazard Stichting, the Radboud Institute for Culture and History, and the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures at Radboud University. The authors thank Demi Schoonenberg and Tommie van Wanrooij for their invaluable help during the editorial process of this book. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 391 6 e-isbn 978 90 4854 440 0 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463723916 nur 621 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Strategic Spatial Planning and Regional Governance in Europe

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233869882 Strategic Spatial Planning and Regional Governance in Europe Article in Journal of the American Planning Association · June 2003 DOI: 10.1080/01944360308976301 CITATIONS READS 310 4,632 3 authors, including: Louis Albrechts Patsy Healey KU Leuven Newcastle University 56 PUBLICATIONS 2,357 CITATIONS 143 PUBLICATIONS 11,407 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: SP2SP. Spatial planning to strategic projects View project SP2SP. Spatial planning to strategic projects View project All content following this page was uploaded by Louis Albrechts on 30 September 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Journal of the American Planning Association ISSN: 0194-4363 (Print) 1939-0130 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjpa20 Strategic Spatial Planning and Regional Governance in Europe Louis Albrechts , Patsy Healey & Klaus R. Kunzmann To cite this article: Louis Albrechts , Patsy Healey & Klaus R. Kunzmann (2003) Strategic Spatial Planning and Regional Governance in Europe, Journal of the American Planning Association, 69:2, 113-129, DOI: 10.1080/01944360308976301 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944360308976301 Published online: 13 Oct 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2065 View related articles Citing articles: 72 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjpa20 Download by: [KU Leuven University Library] Date: 30 September 2015, At: 10:59 LONGER VIEW Strategic Spatial Planning and Regional Governance in Europe Louis Albrechts, Patsy Healey, and Klaus R. -

Dutch Language Union"

208 CASE STIIDY 5: Cultural Vitality and Creativity: The "Dutch Language Union" 1. One of the most recent and also strongest signs of cultural vitality and creativity in The Netherlands (in the largest sense of that name, viz. "The Low Countries") has been the installment of the "Nederlandse Taalunie" ["Dutch Language Union"], as a consequence of the "Verdrag tussen het Koninkrijk Belgie en het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden inzake de Nederlandse Taalunie" ["Treaty between the Kingdom of Belgium and the Kingdom of the Netherlands concerning the Dutch Language Union] which was signed in Brussels on 9 September 1980 and the instruments of ratification of which were exchanged in The Hague on27 January 198216. The text reads that "His Majesty the King of the Belgians and Her Majesty the Queen of the Netherlands ... have decided the installment of a union in the field of the Dutch language"17. The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate why this has to be considered a very strong sign of cultural vitality and creativity in The Netherlands, by explaining the unique character of this treaty as far as international cultural and linguistic relations are concerned. In order to do so I will start with a short expose ofthe historic development of language planning in the Low Countries, then concentrate on the language planning mechanisms devised by the "Taalunie"18 and conclude with some ideas as to the future development and possible applications elsewhere. 2. Historical survey In order to fully understand the Treaty one needs to be informed about the nature of the relationship between Dutch speaking people on both sides of the Dutch-Belgian border. -

Obligation and Self-Interest in the Defence of Belgian Neutrality, 1830-1870

CONTEXTUAL RESEARCH IN LAW CORE VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT BRUSSEL Working Papers No. 2017-2 (August) Permanent Neutrality or Permanent Insecurity? Obligation and Self-Interest in the Defence of Belgian Neutrality, 1830-1870 Frederik Dhondt Please do not cite without prior permission from the author The complete working paper series is available online at http://www.vub.ac.be/CORE/wp Permanent Neutrality or Permanent Insecurity? Obligation and Self-Interest in the Defence of Belgian Neutrality, 1830-1870 Frederik Dhondt1 Introduction ‘we are less complacent than the Swiss, and would not take treaty violations so lightly.’ Baron de Vrière to Sylvain Van de Weyer, Brussels, 28 June 18592 Neutrality is one of the most controversial issues in public international law3 and international relations history.4 Its remoteness from the United Nations system of collective security has rendered its discussion less topical.5 The significance of contemporary self-proclaimed ‘permanent neutrality’ is limited. 6 Recent scholarship has taken up the theme as a general narrative of nineteenth century international relations: between the Congress of Vienna and the Great War, neutrality was the rule, rather than the exception.7 In intellectual history, Belgium’s neutral status is seen as linked to the rise of the ‘Gentle Civilizer of Nations’ at the end of the nineteenth century.8 International lawyers’ and politicians’ activism brought three Noble Peace Prizes (August Beernaert, International Law Institute, Henri La Fontaine). The present contribution focuses on the permanent or compulsory nature of Belgian neutrality in nineteenth century diplomacy, from the country’s inception (1830-1839)9 to the Franco- 1 Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), University of Antwerp, Ghent University/Research Foundation Flanders. -

Clarence Williams

MUNI 2017-2 – Flute 1-2 Shooting the Pistol (Clarence Williams) 1:26 / 1:17 Clarence Williams Orchestra: Ed Allen-co; Charlie Irvis-tb; possibly Arville Harris-cl, as; Alberto Socarras-fl; Clarence Williams-p; Cyrus St. Clair-tu New York, July 1927 78 Paramount 12517, matrix number 2837-2 / CD Frog DGF37 3 I’ll Take Romance (Ben Oakland) 2:39 Bud Shank-fl; Len Mercer and His Strings Bud Shank With Len Mercer Strings: Giulio Libano (trumpet) Appio Squajella (flute, French horn) Glauco Masetti (alto sax) Bud Shank (alto sax, flute) Eraldo Volonte (tenor sax) Fausto Pepetti (baritone sax) Bruno De Filippi (guitar) Don Prell (bass) Jimmy Pratt (drums) with unidentified harp and strings, Len Mercer (arranger, conductor) Milan, Italy, April 4 & 5, 1958 LP World Pacific WP-1251, Music (It) EPM 20096, LPM 2052 4-5 What’ll I Do (Irving Berlin) 1:26 / 1:23 Bud Shank-fl; Bob Cooper-ob; Bud Shank - Bob Cooper Quintet: Bud Shank (alto sax, flute) Bob Cooper (tenor sax, oboe) Howard Roberts (guitar) Don Prell (bass) Chuck Flores (drums) Capitol Studios, Hollywood, CA, first session, November 29, 1956 LP Pacific Jazz X-634, PJ 1226, matr. ST-1894 / CD Mosaic MS-010 6-7 Flute Bag (Rufus Harley) 2:06 / 2:15 Herbie Mann.fl; Rufus Harley-bagpipes; Roy Ayers (vibes) Oliver Collins (piano) James Glenn (bass) Billy Abner (drums) "Village Theatre", NYC, 2nd show, June 3, 1967 LP Atlantic SD 1497, matr. 12589 8-10 Moment’s Notice (John Coltrane) 4:58 / 1:04 / 0:52 Hubert Laws-fl; Ronnie Laws-ts; Bob James-p, elp, arranger; Gene Bertoncini-g; Ron Carter-b; Steve -

Les Émeutes De Novembre 1871 À Bruxelles Et La Revocation Du Ministère D'anethan

RBHC-BTNG, XV, 1984, 1-2, pp. 165-200. LES EMEUTES DE NOVEMBRE 1871 A BRUXELLES ET LA REVOCATION DU MINISTERE D'ANETHAN par Ph. J. VAN TIGGELEN Aspirant au F.N.R.S. En octobre 1871, l'ancien ministre Pierre De Decker est nommé gouverneur du Limbourg. Celui-ci avait été un proche collaborateur du financier André Langrand-Dumonceau, dont la faillite frauduleuse avait entraîné la ruine de milliers de familles. Cette nomination four- nit à l'opposition libérale et en particulier au député Jules Bara, le prétexte d'une offensive contre le ministère catholique du baron d'Anethan. Le 22 novembre, Bara interpelle le gouvernement au sujet de cette nomination. L'attention politique se trouve focalisée sur les séances houleuses de la Chambre des Représentants. Simultanément, des manifestations ont lieu dans les rues de Bruxelles et se répètent dans les derniers jours de novembre. Le 1er décembre 1871, Leopold II, excédé par les troubles journa- liers qui se produisaient à la Chambre des Représentants et sous les fenêtres du Palais, décide de révoquer ses ministres et fait appel au comte de Theux pour constituer un nouveau gouvernement dans la majorité. Les événements de novembre 1871 et la chute du ministère d'Anethan, évoqués de manière toujours ponctuelle dans les grandes synthèses de l'histoire politique de la Belgique, n'ont fait l'objet d'aucune recherche spécifique. Les études d'histoire politique parues durant les dernières années, tout comme les monographies d'histoire bruxelloise, se réfèrent, sur ce point, aux ouvrages plus anciens qui fondent leur argumentation sur des 'Vérités historiques" souvent douteuses (1). -

8Th LRB Meeting Country Profile Netherlands Odijk, Tiberius Final

Country Profile: The Netherlands Jan Odijk & Carole Tiberius Language Resource Board, Amsterdam 2019-03-27 1 Overview • The Dutch Language • Country Report • Identified Data 2 Overview Ø The Dutch Language • Country Report • Identified Data 3 The Dutch Language • App.24 million native speakers: – 16 million in the Netherlands – 6.5 million in Belgium (Flanders) – 400,000 in Suriname. • Dutch is one of the 40 most spoken languages in the world • Official language in the Netherlands and in Flanders • One of the official languages in – Belgium, Surinam, Aruba, Curacao and Sint-Maarten • also spoken – in the EU in France and Germany, – Outside the EU in Brazil, Canada, Indonesia ( Java and Bali), South Africa, and the United States. 4 The Dutch Language • Strong online: – it is one of the 10 most important languages on the Internet and social media. – 8th most used language on Twitter – 9th language on Wikipedia. – .nl is the most well-known extension of the Netherlands: – > 5.6 million .nl sites registered – 5th most popular country extension in the world. – A lot of Dutch also on most .be websites, 5 Overview • The Dutch Language Ø Country Report • Identified Data 6 Translation needs in the public sector • Not centralised (not even within a ministry) • A number of ministries and executing bodies have their own translation department, e.g. – Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Ministry of Justice and Security, especially for interpreting (Foreigners chain, Ministry of Justice and Security) – Ministry of Defense – National Police – General information