Final Revision Garda Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Counter-Terrorism Policing and Special Branch

This document was archived on 31 March 2016 Counter-terrorism policing and Special Branch archived This document was archived on 31 March 2016 Counter-terrorism policing and Special Branch Important facts More information The work of Special Branch Special Branches, which in some police forces are Terrorism remains one of the highest priority risks The Government’s counter- now known as counter-terrorism branches because of to national security. The aim of the Government’s the focus in recent years on counter-terrorism work, counter-terrorism strategy is to reduce this risk so terrorism strategy concentrate on acquiring and developing intelligence that people can go about their lives freely and with The United Kingdom’s strategy for on individuals of national security interest. They also confidence. The police service play a vital role in countering terrorism is known as CONTEST. continue to play important roles in policing extremist making this happen. You can find out more on the Home activity and in the provision of personal protection for Office’s website at: www.homeoffice. Within each force, this role includes: working locally VIPs. gov.uk/publications/counter-terrorism/ to prevent radicalisation; protecting public places, counter-terrorism-strategy transport systems, key infrastructure and other The Strategic Policing Requirement sites from terrorist attack; and being prepared to coordinate the response of the emergency services Community engagement Terrorism is listed as one of the five main threat areas during or after a terrorist attack. in the Strategic Policing Requirement. This sets out Police interaction with the public through national arrangements to protect the public. -

Counter Terrorism Policing and Special Branch Counter Terrorism Policing and Special Branch

Have you got what it takes? Counter terrorism policing and Special Branch Counter terrorism policing and Special Branch • Agree, where appropriate in agreement Important Facts and collaboration with other forces or More Information partners, the contribution that is expected Terrorism remains one of the highest priority risks of them; and The Government’s counter-terrorism to national security. The aim of the Government’s strategy counter-terrorism strategy is to reduce this risk • have the capacity to meet that expectation, so that people can go about their lives freely and taking properly into account the remit and The United Kingdom’s strategy for countering with confidence. The police service play a vital contribution of other bodies (particularly terrorism is known as CONTEST. You can find role in making this happen. national agencies) with responsibilities in out more on the Home Office’s website at: the areas set out in the SPR. www.homeoffice.gov.uk/publications/counter- Within each force, this role includes: working terrorism/counter-terrorism-strategy locally to prevent radicalisation; protecting public In doing so, they must demonstrate that they places, transport systems, key infrastructure have taken into account the need for appropriate Community Engagement and other sites from terrorist attack; and being capacity to: prepared to coordinate the response of the Police interaction with the public through emergency services during or after a terrorist • Contribute to CONTEST by working with neighbourhood policing and other initiatives attack. partners to: (including media campaigns) reassure communities about the risk from terrorism and An important part, primarily by acquiring and – Pursue: identify, disrupt, and investigate remind the public to remain vigilant. -

West Midlands Police ,~, "

eA~If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. '1- Z-9' -& '-- ~t, REPORT OF THE CHIEF CONSTABLE .Report OF THE WEST MIDLANDS POLICE ,~, ", FOR THE OF YEAR 1981 .. 'T':-'f. CHIEF CONSTABLE c::) I o o co I CY") OF THE co , ,-t' ,1' /1 t WEST MIDLANDS POLICE I, ; Chief Constable's Office " Lloyd House ;:, '. .1/' ,.~ Co/more Circus Oueensway i 1 -: , t'l Birmingham B46NO I) ( . 1 \.' ..J. • '''1 '.1 c ; 1", r' , :', L') ~_ " "I 1981 11' Ql'" 1..l' : L_ ;. tf" '+(' t- L :.' (' ll_ :") I ! WEST MIDLANDS POLICE , Police Headquarters Lloyd House Colmore Circus Queensway Telephone No. 021-236 5000 Birmingham B4 6NQ Telex 337321 MEMBERS OF THE POLICE AUTHORITY Chief Constable Deputy Chief Constable Sir Philip Knights CBE QPM Assistant Chief Constables Mr R Broome Chairman: Councillor E T Shore (Birmingham, Sattley) Administration and Supplies Crime Mr L Sharp LL.B Operations Mr D H Gerty LL.B. Mr K J Evans Vice-Chairman: Councillor T J Savage (Birmingham, Erdington) Organisation & Development Mr G E Coles B Jur Personnel & Training Staff Support Mr J B Glynn Mr T Meffen Local Authority Representatives Magistrate Criminal Investigation Department Members Chief Superintendent C W Powell (Operations) Chief Superintendent T Light (Support Services) Ward Chief Administrative Officer Councillor D M Ablett (Dudley, No.6) JD Baker Esq JP FCA ... Chief Superintendent PC J Price MA (Oxon) Councillor D Benny JP (Birmingham, Sandwell) K H Barker Esq Councillor E I Bentley (Meriden, No.1) OBE DL JP FRICS ..;. Personnel Department Councillor D Fysh (Wolverhampton No.4) Captain J E Heydon Chief Superintendent R P Snee Councillor J Hunte (Birmingham,Handsworth) ERD JP i Councillor K RIson (Stourbridge, No.1) J B Pendle Esq JP I. -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949. -

Statement Under Section 62 of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 1998

Investigative report Office of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland: Statement under Section 62 of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 1998. REPORT ON THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF THE DEATH OF MR NEIL McCONVILLE ON 29 APRIL 2003 1 SCHEDULE OF ABBREVIATIONS SB Special Branch PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland RCG Regional Co-ordinating Group VCP Vehicle Check Point ACPO Association of Chief Police Officers (for England, Wales and Northern Ireland) RUC Royal Ulster Constabulary AFO Authorised Firearms Officer UK United Kingdom OPONI Office of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland CPR Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation ECHR European Court of Human Rights Also used as European Convention of Human Rights HMSU Headquarters Mobile Support Unit 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Incident 1. On 29 April 2003 the Police Service of Northern Ireland learned that an individual (Man ‘A’) was to travel to Belfast in a Cavalier car and collect a gun, which may subsequently be used in an attack on an individual. An operation was mounted, directed by HMSU officers. A helicopter was used to monitor the car’s progress. 2. The car was identified and traced in Belfast, and followed to various locations. Police suspected that a gun had been collected at one of these locations. 3. At that stage, Detective Chief Superintendent DD was the Gold Commander, and had strategic responsibility. Detective Superintendent BB, was in charge of the operation, as Silver Commander. As the red Cavalier left Belfast at 1855 hours a decision was made by Detective Superintendent BB that the vehicle must be stopped by police. This was communicated to the officers on the ground. -

Guidelines on SPECIAL BRANCH WORK in the United Kingdom

Guidelines on SPECIAL BRANCH WORK in the United Kingdom Foreword Within the police service, Special Branches play a key role in protecting the public and maintaining order. They acquire and develop intelligence to help protect the public from national security threats, especially terrorism and other extremist activity, and through this they play a valuable role in promoting community safety and cohesion. These revised Guidelines – which replace the Guidelines issued in 1994 – describe the current broad range of Special Branch roles and functions at national, regional and local levels. Although Special Branches continue to have important roles in the policing of extremist activity and in the provision of personal protection for VIPs and Royalty, counter terrorist work, in close co-operation with the Security Service (MI5), is currently the main focus of their activity. The current nature of the terrorist threat requires a flexible response and we are encouraged by the development of regional structures which will enhance this approach. In addition, the appointment of the National Co-ordinator of Special Branch will help ensure an even more effective joined-up approach. We are grateful for the professionalism and efficiency with which all Special Branch Officers carry out their duties and we hope that the revised Guidelines provide a useful tool in describing and putting into context the essential nature of Special Branch working. We commend them to you. The Rt Hon David Blunkett MP Cathy Jamieson MSP The Rt Hon Jane Kennedy MP Secretary of State for Minister for Justice Minister of State for the Home Department Northern Ireland GUIDELINES ON SPECIAL BRANCH WORK IN THE UNITED KINGDOM PURPOSE 1. -

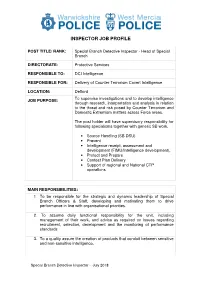

Inspector Job Profile

INSPECTOR JOB PROFILE POST TITLE/ RANK: Special Branch Detective Inspector - Head of Special Branch DIRECTORATE: Protective Services RESPONSIBLE TO: DCI Intelligence RESPONSIBLE FOR: Delivery of Counter Terrorism Covert Intelligence LOCATION: Defford To supervise investigations and to develop intelligence JOB PURPOSE: through research, interpretation and analysis in relation to the threat and risk posed by Counter Terrorism and Domestic Extremism matters across Force areas. The post holder will have supervisory responsibility for following specialisms together with generic SB work. • Source Handling (SB DSU) • Prevent • Intelligence receipt, assessment and development (FIMU/Intelligence development). • Protect and Prepare • Contest Plan Delivery • Support of regional and National CTP operations MAIN RESPONSIBILITIES: 1. To be responsible for the strategic and dynamic leadership of Special Branch Officers & Staff, developing and motivating them to drive performance in line with organisational priorities. 2. To assume daily functional responsibility for the unit, including management of their work, and advice as required on issues regarding recruitment, selection, development and the monitoring of performance standards 3. To a quality assure the creation of products that conduit between sensitive and non-sensitive intelligence. Special Branch Detective Inspector - July 2018 4. Supervise and lead the evaluation and development of new information and intelligence, maximising all investigative and evidential opportunities, prioritising in line the threat and risk posed by individuals and extremist networks. 5. To provide leadership during CT / DE operations through intelligence gathering and development activity. 6. To allocate and supervise enquiries, investigations and operations, working with partners to maximise investigative and evidential opportunities and effectively manage risk. 7. To provide advice and guidance to staff in other business areas on CT/DE, ensuring Police meet partnership and legislative responsibilities. -

A Short History of Army Intelligence

A Short History of Army Intelligence by Michael E. Bigelow, Command Historian, U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command Introduction On July 1, 2012, the Military Intelligence (MI) Branch turned fi fty years old. When it was established in 1962, it was the Army’s fi rst new branch since the Transportation Corps had been formed twenty years earlier. Today, it remains one of the youngest of the Army’s fi fteen basic branches (only Aviation and Special Forces are newer). Yet, while the MI Branch is a relatively recent addition, intelligence operations and functions in the Army stretch back to the Revolutionary War. This article will trace the development of Army Intelligence since the 18th century. This evolution was marked by a slow, but steady progress in establishing itself as a permanent and essential component of the Army and its operations. Army Intelligence in the Revolutionary War In July 1775, GEN George Washington assumed command of the newly established Continental Army near Boston, Massachusetts. Over the next eight years, he dem- onstrated a keen understanding of the importance of MI. Facing British forces that usually outmatched and often outnumbered his own, Washington needed good intelligence to exploit any weaknesses of his adversary while masking those of his own army. With intelligence so imperative to his army’s success, Washington acted as his own chief of intelligence and personally scrutinized the information that came into his headquarters. To gather information about the enemy, the American com- mander depended on the traditional intelligence sources avail- able in the 18th century: scouts and spies. -

The British Intelligence Community in Singapore, 1946-1959: Local

The British intelligence community in Singapore, 1946-1959: Local security, regional coordination and the Cold War in the Far East Alexander Nicholas Shaw Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD The University of Leeds, School of History January 2019 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Alexander Nicholas Shaw to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Alexander Nicholas Shaw in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Acknowledgements I would like to thank all those who have supported me during this project. Firstly, to my funders, the White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. Caryn Douglas and Clare Meadley have always been most encouraging and have never stinted in supplying sausage rolls. At Leeds, I am grateful to my supervisors Simon Ball, Adam Cathcart and, prior to his retirement, Martin Thornton. Emma Chippendale and Joanna Phillips have been invaluable guides in navigating the waters of PhD admin. In Durham, I am indebted to Francis Gotto from Palace Green Library and the Oriental Museum’s Craig Barclay and Rachel Barclay. I never expected to end up curating an exhibition of Asian art when I started researching British intelligence, but Rachel and Craig made that happen. -

The Soviet-Vietnamese Intelligence Relationship During the Vietnam War: Cooperation and Conflict by Merle L

WORKING PAPER #73 The Soviet-Vietnamese Intelligence Relationship during the Vietnam War: Cooperation and Conflict By Merle L. Pribbenow II, December 2014 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

Growth & Development of Intelligence Apparatus During British Colonial

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 4 Issue 4 || April. 2015 || PP.13-19 Growth & Development of Intelligence Apparatus during British Colonial Era in India Shabir Ahmad Reshi1, Dr. Seema Dwivedi2 1(Research Scholar, department of History, Dr. C.V Raman University, Bilaspur, India, 2(Head Of Department, Department of History, Dr. C.V Raman University, Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, ABSTRACT: There is no yard stick for success and failure in any intelligence agency. Any such analysis has to look at its resources, manpower and intelligence gathering processes. In India intelligence gathering processes and the institutions involved in the same developed and took shape from time to time. The earliest mention of the activity of secret agents is found in the Vedic samhitas. In ancient India, the organization of intelligence activity was such as to encompass every sphere affecting the state and its people. Kautilya’s Arthashastra lays out the detailed responsibilities and use of the secret agents for the maintenance of state affairs. Later, the system of intelligence and its uses were felt by different dynasties in the Indian subcontinent. However, the more sophisticated system of intelligence gathering and institutions which shape the present intelligence system of India developed during the british colonization of India. KEY WORDS: Intelligence, Thugee, Intelligence Bureau, CID, Provincial Special Branches I. INTRODUCTION: The mention of Intelligence gathering in the ancient texts like Vedic Samhitas encompasses every sphere of life for the security of the people. In the ancient and medieval periods, the engagement and deployment of spies and informers was by and large personalised; an institutionalised intelligence system grew up only with the arrival of British in the scene of India. -

Royal Police F'orce Antigua 1976

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ------......-~. ~---~iP'~-~-~ ANNUAL REPORT ON THE ORGANIZATION AND AD M I r~ ISTRATI 0 f\I OF THE ROYAL POLICE F'ORCE OF ANTIGUA FOR THE YEAR 1976 -" ..- TABLE OF CONTENT§ PART J; Ge:J.eral Repor-!; - Survey of the ~ea£. ..,:1'" f,ara. No. OOi111D.e.nd & :t:~rsonnel --:r Object of the Foroe 2 Punctions of the Force 3 ether responsibilities 4 Te~ecommunication 5 Recruitment 6 l1ajor Disasters 7 Crimes 8 Traffic and the Traffic Department.; 9 Appointnent-,s 10 Folioe Service Oommission 11 Delegation of Powers Visit of Her rlajesty's Ships and Important Persons to the State 12 Honours and A'lrJards 13 EGtablisbment Increase 14 Change in Nomenclature 15 Establishment 16 Duties and Responsibilities of the Deputy Conmissione~ of 17 Pol:L' '. New Building 18, Cost of running the Police Force & Fire Services 19 ---Fire Services PART II OrganiZation and Arl~inistrati\~ Command 20 Police Servioe Commission 21 Health of Personnel 22 Casualties 23 Discipline 24 Oomposition of the Force 25 Divisional Command 26 Length of Service 27 Clerical Staff 28 Finance - Force and Fire Services 29 Transport 30 Vehicles in working condition ·31 lTr..r • 0.1 Poe:: 1" IF> ~C"I" • jG' T'.n~ " 1''' ~-------------------''''---'\7 -~, PART III Para. No., Recruit Training - 33 d '"'election of Recruits 3'+ Treiniiig General 35 liverseas Courses 36 PART IV Commal1.d 3(,-_ <) Cri1)les 38~-~i . Legal Department 39 ,-' Crime Prevention '+0 Criminal Record Office ,41 ~ 'I Fingerprint and Photography '+2 Scientific Aid 4-3 .