Financing Transport Infrastructure - Current Issues in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian Free

FREE RAILFREIGHT IN COLOUR FOR THE MODELLER AND HISTORIAN PDF David Cable | 96 pages | 02 May 2009 | Ian Allan Publishing | 9780711033641 | English | Surrey, United Kingdom PDF Br Ac Electric Locomotives In Colour Download Book – Best File Book The book also includes a historical examination of the development of electric locomotives, allied to hundreds of color illustrations with detailed captions. An outstanding collection of photographs revealing the life and times of BR-liveried locomotives and rolling stock at a when they could be seen Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian across the network. The AL6 or Class 86 fleet of ac locomotives represents the BRB ' s second generation of main - line electric traction. After introduction of the various new business sectorsInterCity colours appeared in various guiseswith the ' Swallow ' livery being applied from Also in Cab superstructure — Light grey colour aluminium paint considered initially. The crest originally proposed was like that used on the AC electric locomotives then being deliveredbut whether of cast aluminium or a transfer is not quite International Railway Congress at Munich 60 years of age and over should be given the B. Multiple - aspect colour - light signalling has option of retiring on an adequate pension to Consideration had been given to AC Locomotive Group reports activity on various fronts in connection with its comprehensive collection of ac electric locos. Some of the production modelshoweverwill be 25 kV ac electric trains designed to work on BR ' s expanding electrified network. Headlight circuits for locomotives used in multiple - unit operation may be run through the end jumpers to a special selector switch remote Under the tower's jurisdiction are 4 color -light signals and subsidiary signals for Railfreight in Colour for the Modeller and Historian movements. -

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

UTSG Paper Template

January 2012 COWIE: GB Rail Freight Privatisation UTSG Aberdeen Rail Freight in Great Britain – has privatisation made a noticeable difference? Title: Jonathan Cowie Position: Lecturer in Transport Economics Institution: Edinburgh Napier University, SEBE/Transport Research Institute Abstract This paper briefly outlines the main changes brought about by the Railways Act 1993 with regard to the rail freight sector and then examines development of the sector since that time. It finds that although rail freight levels have increased, these in the main have been as a result of changes that have occurred outside of the industry. It also finds little evidence of new operator entry into the rail freight business despite the removal of legal barriers to operation. The paper then gives an overview of the main medium and longer term effects of rail freight reform, principally through a literature review on US railroad deregulation, before examining productivity and scale effects within the British industry since privatisation. What it finds is that in the case of the former productivity has been rising from negative values at the start of the period reviewed, and economies of scale whilst significant should not be viewed as a major barrier to entry and hence do not account for the low level of entry that has occurred since privatisation. The over-riding conclusion is that policy needs to do more and be more innovative in incentivising the industry otherwise long term decline could very quickly set back in. Introduction With open access to rail freight operations introduced in the early 1990s and full privatisation of the industry achieved in 1996, now seems a relevant time to examine the performance and production economics of rail freight in Great Britain. -

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit Contents How to install ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Technical information ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Liveries .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Cab guide ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Keyboard controls ...................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Features .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Global System for Mobile Communication-Railway (GSM-R) ............................................................................. 18 Registering .......................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Deregistering - Method 1 ............................................................................................................................................ -

Eprints.Whiterose.Ac.Uk/2271

This is a repository copy of New Inter-Modal Freight Technology and Cost Comparisons. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/2271/ Monograph: Fowkes, A.S., Nash, C.A. and Tweddle, G. (1989) New Inter-Modal Freight Technology and Cost Comparisons. Working Paper. Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds , Leeds, UK. Working Paper 285 Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Institute of Transport Studies University of Leeds This is an ITS Working Paper produced and published by the University of Leeds. ITS Working Papers are intended to provide information and encourage discussion on a topic in advance of formal publication. They represent only the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views or approval of the sponsors. White Rose Repository URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/2271/ Published paper Fowkes, A.S., Nash, C.A., Tweddle, G. (1989) New Inter-Modal Freight Technology and Cost Comparisons. Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds. Working Paper 285 White Rose Consortium ePrints Repository [email protected] Working Paper 285 December 1989 NEW INTER-MODAL FREIGHT TECHNOLOGY AND COST COMPARISONS AS Fowkes CA Nash G Tweddle ITS Working Papers are intended to provide information and encourage discussion on a topic in advance of formal publication. -

Fastline Simulation

(PRIVATE and not for Publication) F.S. 07131/5 fastline simulation FREIGHT STOCK PACK 03 VEA VANS INSTRUCTIONS FOR INSTALLATION AND USE OF A ROLLING STOCK PACK FOR TRAIN SIMULATOR 2015 This book is for the use of customers, and supersedes as from 13th July 2015, all previous instructions on the installation and use of the above rolling stock pack. THORNTON I. P. FREELY 13th July, 2015 MOVEMENTS MANAGER 1 ORDER OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 Installation ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 The Rolling Stock ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 File Naming Overview.. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 File name options ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 History of the Rolling Stock ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 Temporary Speed Restrictions. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 6 Scenarios ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 7 Known Issues .. -

2-Stroke Diesels on Britain's Rail Network

2-Stroke Diesels on Britain’s Rail Network Rodger Bradley Back in the 1950s, when British Railways was beginning work on the “Modernisation & Re-Equipment Programme” – effectively the changeover from steam to diesel and electric traction – the focus in the diesel world was mainly between high and medium speed engines. On top of which, there was a practical argument to support hydraulic versus electric transmission technology – for main line use, mechanical transmission was never a serious contender. The first main line diesels had appeared in the very last days before nationalisation, and the choice of prime mover was shaped to a great extent by the experience of private industry, and English Electric in particular. The railway workshops had little or no experience in The prototype main-line 2-stroke powered loco for the field, and the better known steam locomotive express passenger service on BR was never repeated. builders had had some less than successful attempts to Photo: Thomas's Pics CC BY 2.0, offer examples of the new diesel locomotives. That https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50662416 said, some of the smaller companies, who had worked with the railways pre-WW2 to supply small shunting Pilot Scheme & Modernisation In the first flush of enthusiasm for the new technology, British Railways announced three types of diesel locomotive to be trialled for main line use; diesel shunters had already been in use for a number of years. The shunting types were a mix of electric and mechanical transmission, paired with 4-stroke diesel engines, and not surprisingly the first main line designs included electric transmission and 4-stroke, medium speed engines. -

UK's New Green Age: a Step Change in Transport Decarbonisation

THE UK’S NEW GREEN AGE A step change in transport decarbonisation January 2021 CONTENTS Alstom in the UK i The UK’s net zero imperative 1 Electrification 7 Hydrogen 15 High speed rail 26 A regional renaissance with green transport for all places 32 Conclusion 43 The New Green Age: a step change in transport decarbonisation ALSTOM IN THE UK Mobility by nature Alstom is a world leader in delivering sustainable and smart mobility systems, from high speed trains, regional and suburban trains, undergrounds (metros), trams and e-buses, to integrated systems, infrastructure, signalling and digital mobility. Alstom has been at the heart of the UK’s rail industry for over a century, building many of the UK’s rail vehicles, half of London’s Tube trains and delivering tram systems. A third of all rail journeys take place on Alstom trains including the iconic Pendolino trains on the West Coast Mainline, which carry 34 million passengers a year. Building on its history, Alstom continues to innovate. One of its most important projects is hydrogen trains—its Coradia iLint has been in service in Germany and Austria, and with Eversholt Rail, it has developed the ‘Breeze’ hydrogen train for the UK. Alstom’s state-of-the-art Transport Technology Centre in Widnes in the Liverpool City Region is its worldwide centre for train modernisation and is where the conversion of trains to hydrogen power will take place. It is among 12 other sites in the UK including Longsight in Manchester and Wembley in London. Across the world Alstom has developed, built and maintained transport systems including high speed rail in every continent that has high speed rail, and mass transit metros and trams schemes including in Nottingham and Dublin. -

Rail Freight Study

Wigan Rail Freight Study Final Report Prepared for: Transport for Greater Manchester & Wigan Council by MDS Transmodal Limited Date: May 2012 Ref: 211076r_ver Final CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Background 2. Freight Activity in North West and Wigan 3. Inventory of Intermodal Terminals in North West 4. Economics of Rail Freight 5. Future Prospects and Opportunities 6. Summary, Conclusions and Next Steps Appendix: Data Tables COPYRIGHT The contents of this document must not be copied or reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of MDS Transmodal 1. INTRODUCTION Wigan Council (alongside Transport for Greater Manchester ± TfGM) commissioned MDS Transmodal in December 2011 to undertake a study into rail freight within the Wigan Council area. The main objective of the study was to identify existing use of rail freight, assess realistic future prospects and determine what kind of facilities would need to be developed. The study will inform the development of a wider transport strategy for Wigan Council. This technical report documHQWSURYLGHVDVXPPDU\RIWKHVWXG\¶VPDLQILQGLQJV,WEURDGO\ covers the following: Background information and data concerning the rail freight sector nationally; An assessment of cargo currently lifted in the North West and Wigan area; An inventory of existing non-bulk rail terminal facilities in the North West and planned terminal developments; The economics of rail freight; Realistic future prospects and opportunities for rail in the Wigan area, including the identification of large freight traffic generators in the Wigan area i.e. organisations which potentially have sufficient traffic, either individually or combined, to generate full-length rail freight services; and Overall conclusions and recommended next steps. -

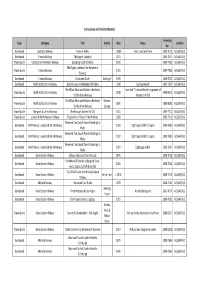

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

The Treachery of Strategic Decisions

The treachery of strategic decisions. An Actor-Network Theory perspective on the strategic decisions that produce new trains in the UK. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael John King. May 2021 Abstract The production of new passenger trains can be characterised as a strategic decision, followed by a manufacturing stage. Typically, competing proposals are developed and refined, often over several years, until one emerges as the winner. The winning proposition will be manufactured and delivered into service some years later to carry passengers for 30 years or more. However, there is a problem: evidence shows UK passenger trains getting heavier over time. Heavy trains increase fuel consumption and emissions, increase track damage and maintenance costs, and these impacts could last for the train’s life and beyond. To address global challenges, like climate change, strategic decisions that produce outcomes like this need to be understood and improved. To understand this phenomenon, I apply Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to Strategic Decision-Making. Using ANT, sometimes described as the sociology of translation, I theorise that different propositions of trains are articulated until one, typically, is selected as the winner to be translated and become a realised train. In this translation process I focus upon the development and articulation of propositions up to the point where a winner is selected. I propose that this occurs within a valuable ‘place’ that I describe as a ‘decision-laboratory’ – a site of active development where various actors can interact, experiment, model, measure, and speculate about the desired new trains. -

Competition Act 1998

Competition Act 1998 Decision of the Office of Rail Regulation* English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited Relating to a finding by the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) of an infringement of the prohibition imposed by section 18 of the Competition Act 1998 (the Act) and Article 82 of the EC Treaty in respect of conduct by English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited. Introduction 1. This decision relates to conduct by English Welsh and Scottish Railway Limited (EWS) in the carriage of coal by rail in Great Britain. 2. The case results from two complaints. 3. On 1 February 2001 Enron Coal Services Limited (ECSL)1 submitted a complaint to the Director of Fair Trading2. Jointly with ECSL, Freightliner Limited (Freightliner) also, within the same complaint, alleged an infringement of the Chapter II prohibition in respect of a locomotive supply agreement between EWS and General Motors Corporation of the United States (General Motors). Together these are referred to as the Complaint. The Complaint alleges: “[…] that English, Welsh and Scottish Railways Limited (‘EWS’), the dominant supplier of rail freight services in England, Wales and Scotland, has systematically and persistently acted to foreclose, deter or limit Enron Coal Services Limited’s (‘ECSL’) participation in the market for the supply of coal to UK industrial users, particularly in the power sector, to the serious detriment of competition in that market. The complaint concerns abusive conduct on the part of EWS as follows. • Discriminatory pricing as between purchasers of coal rail freight services so as to disadvantage ECSL. *Certain information has been excluded from this document in order to comply with the provisions of section 56 of the Competition Act 1998 (confidentiality and disclosure of information) and the general restrictions on disclosure contained at Part 9 of the Enterprise Act 2002.