Thesis Rests with Its Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NR05 Oxford TWAO

OFFICIAL Rule 10(2)(d) Transport and Works Act 1992 The Transport and Works (Applications and Objections Procedure) (England and Wales) Rules 2006 Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order 202X Report summarising consultations undertaken 1 Introduction 1.1 Network Rail Infrastructure Limited ('Network Rail') is making an application to the Secretary of State for Transport for an order under the Transport and Works Act 1992. The proposed order is termed the Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order ('the Order'). 1.2 The purpose of the Order is to facilitate improved capacity and capability on the “Oxford Corridor” (Didcot North Junction to Aynho Junction) to meet the Strategic Business Plan objections for capacity enhancement and journey time improvements. As well as enhancements to rail infrastructure, improvements to highways are being undertaken as part of the works. Together, these form part of Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements ('the Project'). 1.3 The Project forms part of a package of rail enhancement schemes which deliver significant economic and strategic benefits to the wider Oxford area and the country. The enhanced infrastructure in the Oxford area will provide benefits for both freight and passenger services, as well as enable further schemes in this strategically important rail corridor including the introduction of East West Rail services in 2024. 1.4 The works comprised in the Project can be summarised as follows: • Creation of a new ‘through platform’ with improved passenger facilities. • A new station entrance on the western side of the railway. • Replacement of Botley Road Bridge with improvements to the highway, cycle and footways. -

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

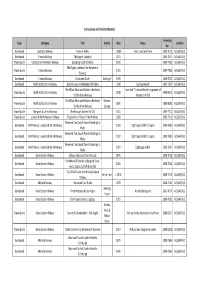

Appendix C. List of Consultees

Appendix C. List of Consultees C.1. Introduction C.1.1 This appendix provides a list of the organisations consulted under section 42, section 47 and section 48 of the Planning Act 2008 . C.2. Section 42(1)(a) Prescribed Consultees C.2.1 Prescribed consultees are set out under Schedule 1 of the Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 ; these are outlined in Appendix Table A below. Any variation from the list of organisations set out in Schedule 1 is clarified within column 3 of the table. C.2.2 The Planning Inspectorate provided a list of prescribed consultation bodies in accordance with Regulation 9(1)(b) of the EIA Regulations and Advice Note three 1 (see Appendix A ), referred to as the “Regulation 9 list”. Those consultees included in the Reg 9 list are included in Table A, B and C. Those consultees that were not previously identified as a prescribed consultee as per Schedule 1 are identified with asterisk (*), and were consulted in the same way as the Schedule 1 consultees. C.2.3 The list of parish councils consulted under section 42 (1) (a) is outlined separately in Appendix Table C. The list of statutory undertakers consulted under Section 42 (1) (a) is outlined separately in Appendix Table B . C.2.4 Organisations noted in Appendix Tables A, B and C were issued with a copy of the Section 48 notice, notifying them of the proposed application and with consultation information, including the consultation brochure and details of how to respond. Appendix Table A: Prescribed Consultees Variation from the schedule where Consultee Organisation applicable The proposed application is not likely The Welsh Ministers N/A to affect land in Wales. -

The Electric Telegraph

To Mark, Karen and Paul CONTENTS page ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENTS TO 1837 13 Early experiments—Francis Ronalds—Cooke and Wheatstone—successful experiment on the London & Birmingham Railway 2 `THE CORDS THAT HUNG TAWELL' 29 Use on the Great Western and Blackwall railways—the Tawell murder—incorporation of the Electric Tele- graph Company—end of the pioneering stage 3 DEVELOPMENT UNDER THE COMPANIES 46 Early difficulties—rivalry between the Electric and the Magnetic—the telegraph in London—the overhouse system—private telegraphs and the press 4 AN ANALYSIS OF THE TELEGRAPH INDUSTRY TO 1868 73 The inland network—sources of capital—the railway interest—analysis of shareholdings—instruments- working expenses—employment of women—risks of submarine telegraphy—investment rating 5 ACHIEVEMENT IN SUBMARINE TELEGRAPHY I o The first cross-Channel links—the Atlantic cable— links with India—submarine cable maintenance com- panies 6 THE CASE FOR PUBLIC ENTERPRISE 119 Background to the nationalisation debate—public attitudes—the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce— Frank Ives. Scudamore reports—comparison with continental telegraph systems 7 NATIONALISATION 1868 138 Background to the Telegraph Bill 1868—tactics of the 7 8 CONTENTS Page companies—attitudes of the press—the political situa- tion—the Select Committee of 1868—agreement with the companies 8 THE TELEGRAPH ACTS 154 Terms granted to the telegraph and railway companies under the 1868 Act—implications of the 1869 telegraph monopoly 9 THE POST OFFICE TELEGRAPH 176 The period 87o-1914—reorganisation of the -

ASTRODYNAMICS Z^S Hovercraft

UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Postgraduate Courses At CRANFIELD (Departments of Astronomy and Aeronautics & Fluid Mechanics) Diploma Course in Air Transport ASTRODYNAMICS Engineering Commencing October 1969 The College of Aeronautics offers a one-year Subjects of Study residential postgraduate course in Air Transport Celestial Mechanics and Astrodynamics Engineering designed for engineers and scientists of graduate standard concerned with or interested Numerical Methods and Programming in the airline industry and the transport aircraft Environmental Problems manufacturing industry. Propulsion Navigation and Stabilisation The syllabus covers the operational, engineering Re-entry Problems and economic implications of air transport together Joint Project on the Requirements of a Hypothetical Mission with the directly related aspects of systems, materials, design and propulsion. Entry requirement: Degree or equivalent in Science Full use is made of College aircraft and extensive (Astronomy, Mathematics or Physics) or Engineering. laboratory demonstration resources of all Departments to illustrate the operational aspects Duration: One Calendar Year with examination in of the subject. September 1970. Advice given on financial aid. Application forms and further information obtainable Further information and forms of application from: from The Registrar, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, The Registrar, The CoUege of Aeronautics, W2, Scotland. Cranfield, Bedford. DIRECTORATE ELECTRONICS RESEARCH AND Z^S Hovercraft DEVELOPMENT (AIR) Ministry of Technology -

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

The Treachery of Strategic Decisions

The treachery of strategic decisions. An Actor-Network Theory perspective on the strategic decisions that produce new trains in the UK. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael John King. May 2021 Abstract The production of new passenger trains can be characterised as a strategic decision, followed by a manufacturing stage. Typically, competing proposals are developed and refined, often over several years, until one emerges as the winner. The winning proposition will be manufactured and delivered into service some years later to carry passengers for 30 years or more. However, there is a problem: evidence shows UK passenger trains getting heavier over time. Heavy trains increase fuel consumption and emissions, increase track damage and maintenance costs, and these impacts could last for the train’s life and beyond. To address global challenges, like climate change, strategic decisions that produce outcomes like this need to be understood and improved. To understand this phenomenon, I apply Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to Strategic Decision-Making. Using ANT, sometimes described as the sociology of translation, I theorise that different propositions of trains are articulated until one, typically, is selected as the winner to be translated and become a realised train. In this translation process I focus upon the development and articulation of propositions up to the point where a winner is selected. I propose that this occurs within a valuable ‘place’ that I describe as a ‘decision-laboratory’ – a site of active development where various actors can interact, experiment, model, measure, and speculate about the desired new trains. -

![Dear [Click and Type Name]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1061/dear-click-and-type-name-1611061.webp)

Dear [Click and Type Name]

Colin Dunn Date: 3 January 2020 TWA Unit Enquiries to: Michael Wilks Department for Transport Tel: 01473 264064 Great Minster House Email: [email protected] 33 Horseferry Road London SW1P 4DR Your ref: TR010023 Our ref: SCC/LLTC/POST-EX/Crown Land Dear Mr Dunn, Lake Lothing Third Crossing ('LLTC') – DCO Application – Reference TR010023 Response to the Secretary of State’s consultation letter dated 10 December 2019 requesting comments from the Applicant in relation to a request for Crown authority consent in connection with the LLTC This letter constitutes the formal response of Suffolk County Council ('the Applicant') to the Secretary of State’s 'consultation letter' dated 10 December 2019, published on the Planning Inspectorate’s website and received by the Applicant on 11 December 2019. The Applicant notes that the Secretary of State has not yet received a response to its consultation letter dated 7 October 2019 addressed to DfT Estates, requesting an update on the position of that party, as the appropriate Crown authority in relation to the Applicant’s request for Crown authority consent made in respect of land proposed to be acquired and used for the purposes of the LLTC. Applicant’s request for Crown authority consent As the Secretary of State may be aware, the Applicant originally requested Crown authority consent in connection with the LLTC on 25 June 2018, in advance of submitting its application for development consent for the LLTC to the Planning Inspectorate on 13 July 2018. Since that time, the Applicant has made repeated attempts to engage with DfT Estates (including providing/re-providing a full package of supporting documentation on at least three separate occasions, with numerous follow-up communications) with the aim of securing the necessary Crown authority consent. -

Financial Report British Railways Board 29 September 2013

FINANCIAL REPORT BRITISH RAILWAYS BOARD 29 SEPTEMBER 2013 Registered Office One Kemble Street London United Kingdom WC2B 4AN Financial Report British Railways Board (For the period ended 29 September 2013) Presented to the House of Commons pursuant to Section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 14 May 2014 HC 1238 © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v.2. To view this licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2/ or email [email protected] Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication, please call 0300 330 3000 Print ISBN 9781474102575 Web ISBN 9781474102582 Printed in the UK by the Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID 2640819 05/14 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum FINANCIAL REPORT BRITISH RAILWAYS BOARD 29 SEPTEMBER 2013 Registered Office One Kemble Street London United Kingdom WC2B 4AN British Railways Board is a statutory corporation created by the Transport Act 1962. British Railways Board - Financial Report- 29 September 2013 CONTENTS MEMBERS………...………………………………………………………………… 3 CHAIRMAN'S STATEMENT………...……………………………………………. 4 INTRODUCTION TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ................................... 5 STATEMENT OF BOARD MEMBERS’ RESPONSIBILITIES ......................... 6 MEMBERS’ REPORT ...................................................................................... 7 OPERATING REVIEW ..................................................................................... 7 FINANCIAL REVIEW ..................................................................................... 11 STATEMENT ON INTERNAL CONTROL ..................................................... -

PERSONAL and CONFIDENTIAL 3N the Rt Hon Margaret Thatcher MP

PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL DEPARTML.0 k 2 MARSHAN1 STREET LONDc. S;VriP 3n The Rt Hon Margaret Thatcher MP 2 2 December 1982 FIVE-YEAR FCRWARD LOOK In response to your letter of 16 September I am submitting my report on a "forward look" at my Department's programmes for the next five years. We have already taken some major steps: National Freight Company Limited privatised Express bus services deregulated virtually all motorway service areas sold design of motorway and trunk road schemes transferred to the private sector more competitive tendering for local road works We have action immediately in hand now to: privatise British Transport Docks Board privatise heavy goods vehicle and bus testing privatise British Rail hotels contain subsidies to public transport in London and other metropolitan areas, and open the way to more private sector operators PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL 1 PERSONAL AND CONFIDENTIAL In the next Parliament we should: tackle the major issues of railway policy, following the Serpell report set up a new structure for public transport in London and push ahead with the break-up of the large public transport monolith here and in other cities introduce private capital into the National Bus Company sweep away unnecessary barriers to innovations in rural transport bring the ports to stand on their own feet, and tackle the National Dock Labour Scheme. Throughout the period we must maintain and if possible increase the level of worthwhile investment in roads to meet growing demand. In particular, we should: complete the national motorway and trunk road network to satisfactory standards as quickly as possible keep up the momentum in building by-passes to take heavy traffic away from communities These aims will nequire a commitment of capital funds through the 1960s, with private finance, if possible, providing a source of additional money. -

Life Stories

Looking back Loco-spotting BR remembered... You couldn’t pass through a large station in the Fifties and Sixties without seeing a gaggle of school-uniformed boys (never girls) at the platform end scribbling down engine numbers. years on Tens of thousands of boys spent all their 70 spare time and pocket money in pursuit of elusive locomotives. Today, the rather sneering Railway writer and former editor of Steam World magazine Barry McLoughlin N O T description ‘anorak’ is frequently applied to E L T T celebrates the 70th anniversary of the formation of British Railways trainspotters. And yes, we did wear anoraks and E N L we usually carried duffel bags crammed with Tizer U A P bottles and sandwiches. © RITAIN’S RAILWAY network used economic forces – most importantly, the railway technology, branding, marketing For my fellow ‘gricers’ and me, our favourite There’s no mistaking the huge BR B be a vast adventure playground for massive expansion of road travel. and organisation. spotting location wasn’t at a station but by the double-arrow logo on the side of this Class my group of friends during our It’s easy to become misty-eyed As with the NHS – founded in the same busy West Coast Main Line just south of 37 diesel – one of the more successful of teenage trainspotting expeditions. about BR: it wasn’t all gleaming green year – it was a substantial achievement Warrington. From our vantage point near the the Modernisation Plan locomotives – on an In the Sixties we scaled signals and bridges, engines, spotless ‘blood and custard’ after six years of total war. -

The Evolution of British Railways 1909-2009

The Evolution of British Railways 1909-2009 Britain’s Railways and The Railway Study Association 1909-2009 previously published in 2009 as part of A Century of Change 2019 Introduction to Second Edition Mike Horne FCILT MIRO This book was originally published by the name of ‘A Century of Change’ to commemorate the centenary of the Railway Study Association (RSA) in 1909; the Association is now the Railway Study Forum of the Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport. Plenty has already been written about the railways of Britain. When the time came to celebrate the activities of the RSA, it occurred to this author that there was something missing. I felt that although it is self-evident that the railway today is very different to that of a century ago, the real point was that railways have been in a state of constant evolution, in part to respond to the changing conditions of the country and in part because of technological change. More importantly, this change will continue. Few people entering the in- dustry today can have much conception of what these changes will be, but change there will be: big changes too. What I wanted to highlight is the huge way the railway has altered, particularly in its technology and operational practices. This has happened, with great success, under diffi cult political and fi nancial conditions. Although the railway has lost much of its market share, the numbers of people carried today have recovered dramatically, and the fact this has been done on a much smaller system is an in- credible achievement that needs to be promoted.