Sheppard 202003722 Thesis WREO.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NR05 Oxford TWAO

OFFICIAL Rule 10(2)(d) Transport and Works Act 1992 The Transport and Works (Applications and Objections Procedure) (England and Wales) Rules 2006 Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order 202X Report summarising consultations undertaken 1 Introduction 1.1 Network Rail Infrastructure Limited ('Network Rail') is making an application to the Secretary of State for Transport for an order under the Transport and Works Act 1992. The proposed order is termed the Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order ('the Order'). 1.2 The purpose of the Order is to facilitate improved capacity and capability on the “Oxford Corridor” (Didcot North Junction to Aynho Junction) to meet the Strategic Business Plan objections for capacity enhancement and journey time improvements. As well as enhancements to rail infrastructure, improvements to highways are being undertaken as part of the works. Together, these form part of Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements ('the Project'). 1.3 The Project forms part of a package of rail enhancement schemes which deliver significant economic and strategic benefits to the wider Oxford area and the country. The enhanced infrastructure in the Oxford area will provide benefits for both freight and passenger services, as well as enable further schemes in this strategically important rail corridor including the introduction of East West Rail services in 2024. 1.4 The works comprised in the Project can be summarised as follows: • Creation of a new ‘through platform’ with improved passenger facilities. • A new station entrance on the western side of the railway. • Replacement of Botley Road Bridge with improvements to the highway, cycle and footways. -

Exhibit Overview

Exhibit Overview Exhibit Summary All aboard to explore! Shrill whistles and the unmistakable clatter of wheels rolling over rails float across the pastoral landscape. Friendly chatter fills the air. It is a unique land that has held a special place in the hearts and imaginations of children for generations. Welcome to the Island of Sodor! In Thomas & Friends: Explore the Rails children explore and interact with the familiar faces and sights from HIT Entertainment’s popular series. Designed for children 2 through 7 (and their adult caregivers) the exhibit combines exciting play opportunities with important concepts in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM), and an emphasis on developing 21st century skills. These ideas are woven and layered throughout the exhibit, creating an experience that speaks to a diversity of interests, age groups, and learning styles. As they travel through the space, children help Thomas and his friends solve a variety of challenges. These interactive opportunities range from simple sorting and shape identification to more complicated engineering obstacles. As children confront new challenges and test their skills, the smiling faces of Thomas, Percy, and others are there to offer encouragement and remind children of how “useful” we all are. 6 Rationale “Lying in bed as a child I would hear a heavy goods train coming in and stopping at Box Station…There was no doubt in my mind that steam engines all had definite personalities. I would hear them snorting up the grade and little imagination was needed to hear in the puffings and pantings of the two engines the conversations they were having with one another: "I can't do it! I can't do it!" "Yes you can! Yes you can!" -Rev. -

The Elsworth Chronicle

The Elsworth Chronicle Issue No. 11 December 1997 SPOTLIGHT ON REV. DR. MICHAEL REISS PRIEST IN CHARGE AT HOLY TRINITY CHURCH, ELSWORTH The Rev. Dr. Michael Reiss has been appointed to Elsworth to serve the church and people following the retirement of Rev. Hugh Mosedale. Many readers will have met Michael and, no doubt, been curious about his background in the warm inquiring manner which marks our village. Michael is a scientist and a Christian, being one of many who contrary to seeing conflict between the two, finds they are complementary. He studied biology at Trinity College here in Cambridge both as an undergraduate and post graduate student, being awarded his doctorate in 1982. Subsequently he pursued post-doctoral research, and following studies for the Post Graduate Certificate in Education - also in Cambridge - he taught for 5 years at Hills Road 6th Form College before being appointed to the Department of Education in the University. In 1994 he took up his present post as senior lecturer in biology at Homerton College, Cambridge. Michael's formal preparation to serve God through the church ran in parallel with his scientific research and teaching, studying as a student of theology from 1987-90 under the East Anglian Ministerial Training Course. As such, studies had to be fitted in alongside his everyday work. Since ordination he has helped during the interregnum at Bourn and Kingston from 1993-4 and at Toft in 1995. Again his endeavours had to be fitted in with his full-time work. Now at Elsworth, Knapwell and Boxworth until a full-time minister is in office, Michael has deliberately chosen to integrate his work in the church with his at academic interests rather than pursue a full-time ministry within the church. -

Thomas the Tank Engine Complete Collection PDF Book

THOMAS THE TANK ENGINE COMPLETE COLLECTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rev. Wilbert Vere Awdry | 416 pages | 09 Oct 2014 | Egmont UK Ltd | 9781405275576 | English | London, United Kingdom Thomas the Tank Engine Complete Collection PDF Book Random House Children's Books. Want to Read saving…. View Product. The Very Quiet Cricket. Reginald Payne being the unknown, to many, second artist of the series, after the first had an unlikable style, Payne created the original iconic look of Thomas and his friends. And have! We've got you covered with the buzziest new releases of the day. Very good in a very good moderate shelf wear and creasing dust jacket. Awdry, made up to accompany this wonderful toy were first published in Thomas and his friends are trains on the island of Sodor. I loved this so much. A timeless classic that has influenced many, ever since the first book, 'The Three Railway Engines', was published in , with the second book in entitled 'Thomas The Tank Engine', the 'Railway Series', or the 'Thomas the Tank Engine stories', as they are now called, has had an impact on the lives of many a child or adult, culminating in the Reverend's son, Christopher, continuing the range with sixteen more books, the beginning of the hit series in , and a devoted fanbase. ISBN Reprint. I'll confess that I a The author of the Thomas books was a clergyman, and I'm torn between two thoughts. Hardcover —. Please try again later. Still in plastic packaging. We spent a month or two reading through this book. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

The Titfield Thunderbolt and the Camerton Branch'

Wells Railway Fraternity The guest speaker at our meeting at Wells Town Hall on 8th February was Simon Castens and his subject was 'The Titfield Thunderbolt and the Camerton Branch'. After a computer hitch had been overcome we settled down to an evening of pure nostalgia. Simon began with a brief outline of the history of the branch line which linked Camerton with the Avon Valley at Limpley Stoke. The line was partly built on the route of the old Somerset Coal Canal and opened in 1910. It was destined to have a fairly short life of just under a half century, ending shortly after Camerton Colliery closed in 1950 - the other major colliery served by the line, at Dunkerton, had stopped working earlier, in the 1930s. The line was then used by the BR Bridge Department for storage and the rails were finally lifted in 1958. Simon pointed out that when Ealing Studios decided to make the film 'The Titfield Thunderbolt', the Talyllyn Railway was the only enthusiast-run line anywhere and speculation has taken place as to whether the little Welsh railway was the inspiration for Tibby Clarke's story. There can be little doubt that the film served as encouragement for the movement which has resulted in today's preserved and heritage railway tourist industry. With the help of old photographs of the line and stills from the film, Simon then spoke of the making of the film in July and August 1952. The station at Monkton Combe served as that of the fictional village of Titfield, the name being a composite of Titsey and Limpsfield, two adjoining villages in Surrey. -

Appendix C. List of Consultees

Appendix C. List of Consultees C.1. Introduction C.1.1 This appendix provides a list of the organisations consulted under section 42, section 47 and section 48 of the Planning Act 2008 . C.2. Section 42(1)(a) Prescribed Consultees C.2.1 Prescribed consultees are set out under Schedule 1 of the Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009 ; these are outlined in Appendix Table A below. Any variation from the list of organisations set out in Schedule 1 is clarified within column 3 of the table. C.2.2 The Planning Inspectorate provided a list of prescribed consultation bodies in accordance with Regulation 9(1)(b) of the EIA Regulations and Advice Note three 1 (see Appendix A ), referred to as the “Regulation 9 list”. Those consultees included in the Reg 9 list are included in Table A, B and C. Those consultees that were not previously identified as a prescribed consultee as per Schedule 1 are identified with asterisk (*), and were consulted in the same way as the Schedule 1 consultees. C.2.3 The list of parish councils consulted under section 42 (1) (a) is outlined separately in Appendix Table C. The list of statutory undertakers consulted under Section 42 (1) (a) is outlined separately in Appendix Table B . C.2.4 Organisations noted in Appendix Tables A, B and C were issued with a copy of the Section 48 notice, notifying them of the proposed application and with consultation information, including the consultation brochure and details of how to respond. Appendix Table A: Prescribed Consultees Variation from the schedule where Consultee Organisation applicable The proposed application is not likely The Welsh Ministers N/A to affect land in Wales. -

The Electric Telegraph

To Mark, Karen and Paul CONTENTS page ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENTS TO 1837 13 Early experiments—Francis Ronalds—Cooke and Wheatstone—successful experiment on the London & Birmingham Railway 2 `THE CORDS THAT HUNG TAWELL' 29 Use on the Great Western and Blackwall railways—the Tawell murder—incorporation of the Electric Tele- graph Company—end of the pioneering stage 3 DEVELOPMENT UNDER THE COMPANIES 46 Early difficulties—rivalry between the Electric and the Magnetic—the telegraph in London—the overhouse system—private telegraphs and the press 4 AN ANALYSIS OF THE TELEGRAPH INDUSTRY TO 1868 73 The inland network—sources of capital—the railway interest—analysis of shareholdings—instruments- working expenses—employment of women—risks of submarine telegraphy—investment rating 5 ACHIEVEMENT IN SUBMARINE TELEGRAPHY I o The first cross-Channel links—the Atlantic cable— links with India—submarine cable maintenance com- panies 6 THE CASE FOR PUBLIC ENTERPRISE 119 Background to the nationalisation debate—public attitudes—the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce— Frank Ives. Scudamore reports—comparison with continental telegraph systems 7 NATIONALISATION 1868 138 Background to the Telegraph Bill 1868—tactics of the 7 8 CONTENTS Page companies—attitudes of the press—the political situa- tion—the Select Committee of 1868—agreement with the companies 8 THE TELEGRAPH ACTS 154 Terms granted to the telegraph and railway companies under the 1868 Act—implications of the 1869 telegraph monopoly 9 THE POST OFFICE TELEGRAPH 176 The period 87o-1914—reorganisation of the -

How to Get On-Board with Tornado

Follow us on www.a1steam.com David Chandler Darlington Locomotive Works Visit Darlington Locomotive Works on one of our open days and THE A1 STEAM LOCOMOTIVE TRUST How to get on-board see where No. 60163 Tornado was completed and No. 2007 Prince Follow uswww.a1steam.com on TH of Wales is under construction. 30 ANNIVERSARY APPEALS Visit: with Tornado The works is open on the first and third Saturday of each month between 11:00hrs and 16:00hrs. Special arrangements can be made for parties from interested clubs and societies. Our grateful thanks go to Darlington Borough Council for their continued support of The A1 Steam Locomotive Trust and The many ways you can Darlington Locomotive Works. support our work Volunteering There are many ways in which Mandy Grant Photos: you can help us to build No. 2007 Prince of Wales and keep No. 60163 Tornado operating on the main line. There are opportunities to help wherever you live. Britain’s 100mph Please see our websites www.a1steam.com and www.p2steam.com or contact main line steam locomotive [email protected] for more information. Become a weekly Covenantor and help to keep No. 60163 Tornado Legacy Giving on the main line. A further way in which you can help to keep No. A bequest left in your Will will not be used for the To find out more about becoming a Covenantor - regular donor - for No.60163 Tornado from 60163 Tornado on the main line or build No. 2007 general day to day expenses of running No. 60163 only £2.50 a week, please visit www.a1steam.com, email [email protected] Prince of Wales is by establishing a Legacy. -

Syd Pearson | BFI Syd Pearson

23/11/2020 Syd Pearson | BFI Syd Pearson Save 0 Filmography Show less 1971 Creatures the World Forgot Special Effects 1969 Desert Journey Special Effects 1969 Autokill Special Effects 1966 The Heroes of Telemark [Special Effects] 1965 The Secret of Blood Island Special Effects 1965 The Brigand of Kandahar Special Effects 1964 The Long Ships Special Effects 1964 The Gorgon Special Effects 1962 In Search of the Castaways Special Effects 1960 The Brides of Dracula Special Effects 1959 Too Many Crooks [Special Processes] 1959 North West Frontier Special Effects 1959 The Hound of the Baskervilles Special Effects 1959 Ferry to Hong Kong Special Effects 1958 Dracula Special Effects 1957 The Steel Bayonet Special Effects 1957 Campbell's Kingdom Special Effects 1956 The Ladykillers Special Effects 1956 House of Secrets Special Processes (uncredited) 1956 Reach for the Sky Models (uncredited) 1955 Out of the Clouds Special Effects 1955 The Ship That Died of Shame Special Effects 1955 The Night My Number Came Up Special Effects 1955 Touch and Go Special Effects 1954 The Love Lottery Special Effects 1954 The 'Maggie' Special Effects https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2baabc6ce7 1/2 23/11/2020 Syd Pearson | BFI 1953 The Cruel Sea Special Effects 1953 The Titfield Thunderbolt Special Effects 1952 His Excellency Special Effects 1952 Mandy [Special Effects] 1952 I Believe in You Special Effects (uncredited) 1952 The Gentle Gunman Special Effects 1952 Secret People Special Effects 1951 Pool of London Special Effects 1951 The Man in the White Suit Special Effects 1951 The Lavender Hill Mob Special Effects 1950 Cage of Gold Special Effects 1950 Dance Hall Special Effects 1950 The Magnet Special Effects 1949 Kind Hearts and Coronets Special Effects 1949 Train of Events Special Effects 1949 Whisky Galore! Special Effects 1948 Scott of the Antarctic Special Effects 1947 The October Man [Stage Effects] [Model Miniatures] 1947 Black Narcissus [Synthetic Pictorial Effects] https://www2.bfi.org.uk/films-tv-people/4ce2baabc6ce7 2/2. -

ASTRODYNAMICS Z^S Hovercraft

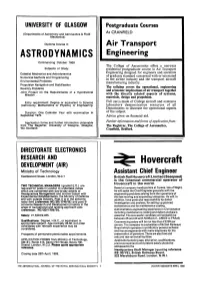

UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Postgraduate Courses At CRANFIELD (Departments of Astronomy and Aeronautics & Fluid Mechanics) Diploma Course in Air Transport ASTRODYNAMICS Engineering Commencing October 1969 The College of Aeronautics offers a one-year Subjects of Study residential postgraduate course in Air Transport Celestial Mechanics and Astrodynamics Engineering designed for engineers and scientists of graduate standard concerned with or interested Numerical Methods and Programming in the airline industry and the transport aircraft Environmental Problems manufacturing industry. Propulsion Navigation and Stabilisation The syllabus covers the operational, engineering Re-entry Problems and economic implications of air transport together Joint Project on the Requirements of a Hypothetical Mission with the directly related aspects of systems, materials, design and propulsion. Entry requirement: Degree or equivalent in Science Full use is made of College aircraft and extensive (Astronomy, Mathematics or Physics) or Engineering. laboratory demonstration resources of all Departments to illustrate the operational aspects Duration: One Calendar Year with examination in of the subject. September 1970. Advice given on financial aid. Application forms and further information obtainable Further information and forms of application from: from The Registrar, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, The Registrar, The CoUege of Aeronautics, W2, Scotland. Cranfield, Bedford. DIRECTORATE ELECTRONICS RESEARCH AND Z^S Hovercraft DEVELOPMENT (AIR) Ministry of Technology -

Public Transport Buildings of Metropolitan Adelaide

AÚ¡ University of Adelaide t4 É .8.'ìt T PUBLIC TRANSPORT BUILDII\GS OF METROPOLTTAN ADELAIDE 1839 - 1990 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Architecture and Planning in candidacy for the degree of Master of Architectural Studies by ANDREW KELT (û, r're ¡-\ ., r ¡ r .\ ¡r , i,,' i \ September 1990 ERRATA p.vl Ljne2}oBSERVATIONshouldreadOBSERVATIONS 8 should read Moxham p. 43 footnote Morham facilities p.75 line 2 should read line 19 should read available Labor p.B0 line 7 I-abour should read p. r28 line 8 Omit it read p.134 Iine 9 PerematorilY should PerernPtorilY should read droP p, 158 line L2 group read woulC p.230 line L wold should PROLOGUE SESQUICENTENARY OF PUBLIC TRANSPORT The one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of public transport in South Australia occurred in early 1989, during the research for this thesis. The event passed unnoticed amongst the plethora of more noteworthy public occasions. Chapter 2 of this thesis records that a certain Mr. Sp"y, with his daily vanload of passengers and goods, started the first regular service operating between the City and Port Adelaide. The writer accords full credit to this unsung progenitor of the chain of events portrayed in the following pages, whose humble horse drawn char ò bancs set out on its inaugural joumey, in all probability on 28 January L839. lll ACKNO\ryLEDGMENTS I would like to record my grateful thanks to those who have given me assistance in gathering information for this thesis, and also those who have commented on specific items in the text.