Land Assessments and Settlement History in Sutherland and Easter Ross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Item 6. Golspie Associated School Group Overview

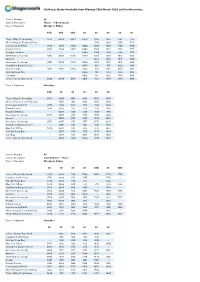

Agenda Item 6 Report No SCC/11/20 HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Area Committee Date: 05/11/2020 Report Title: Golspie Associated School Group Overview Report By: ECO Education 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 This report provides an update of key information in relation to the schools within the Golspie Associated School Group (ASG) and provides useful updated links to further information in relation to these schools. 1.2 The primary schools in this area serve around 322 pupils, with the secondary school serving 244 young people. ASG roll projections can be found at: http://www.highland.gov.uk/schoolrollforecasts 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to: scrutinise and not the content of the report. School Information Secondary – Link to Golspie High webpage Primary http://www.highland.gov.uk/directory/44/schools/search School Link to School Webpage Brora Primary School Brora Primary webpage Golspie Primary School Golspie Primary webpage Helmsdale Primary School Helmsdale Primary webpage Lairg Primary School Lairg Primary webpage Rogart Primary School Rogart Primary webpage Rosehall Primary School Rosehall Primary webpage © Denotes school part of a “cluster” management arrangement Date of Latest Link to Education School Published Scotland Pages Report Golspie High School Mar-19 Golspie High Inspection Brora Primary School Apr-10 Brora Primary Inspection Golspie Primary School Jun-17 Golspie Primary Inspection Helmsdale Primary School Jun-10 Helmsdale Primary Inspection Lairg Primary School Mar-20 Lairg Primary Inspection Rogart Primary -

Place-Names in and Around the Fleet Valley ==== D ==== Daffin Daffin Is a Farm at the Head of the Cleugh of Doon Above Carsluith

Place-names in and around the Fleet Valley ==== D ==== Daffin Daffin is a farm at the head of the Cleugh of Doon above Carsluith. There is a Daffin Tree marked on the 1st edition OS map at Killochy in Balmaclellan parish, and Daffin Hill in this location on current OS maps, across the Dee from Kenmure Castle; Castle Daffin is a hill in Parton parish and a house by Auchencairn. This is likely to be Gaelic *Dà pheiginn ‘two pennylands’. Peighinn is ‘a penny’, but in place-names it refers to a unit of land, based on yield rather than area. It probably originated in the Gaelic-Norse context of Argyll and the southern Hebrides, and was introduced into the south-west by the Gall- Ghàidheil (see Ardwell above). It occurs in place-names in Galloway and, especially, Carrick as ‘Pin- ‘ as first element, ‘-fin’ with ‘softened ‘ph’ after a numeral or other pre-positioned adjective. Originally a pennyland was a relatively small division of a davoch (dabhach, see Cullendoch above), but in the south-west places whose names contain this element appear in mediaeval records as holdings of relatively substantial landowners, comprising good extents of pasture, meadow and woodland as well as the arable core, and yielding much higher taxes than the pennylands further north. Indeed, peighinn may have come to be used more generally in the region for a fairly substantial estate without implying a specific valuation. *Dà pheiginn ‘two pennylands’ would, then, have been a large and productive landholding. However, a Scots origin is also possible, or if the origin was Gaelic, reinterpretation by Scots speakers is possible: daffin or daffen is a Scots word for ‘daffodil’, but as a verb, daffin(g) is ‘playing daft, larking about’. -

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Rosehall Information

USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS Rosehall Information POLICE Emergency = 999 Non-emergency NHS 24 = 111 No 21 January 2021 DOCTORS Dr Aline Marshall and Dr Scott Smith PLEASE BE AWARE THAT, DUE TO COVID-RELATED RESTRICTIONS Health Centre, Lairg: tel 01549 402 007 ALL TIMES LISTED SHOULD BE CHECKED Drs C & J Mair and Dr S Carbarns This Information Sheet is produced for the benefit of all residents of Creich Surgery, Bonar Bridge: tel 01863 766 379 Rosehall and to welcome newcomers into our community DENTISTS K Baxendale / Geddes: 01848 621613 / 633019 Kirsty Ramsey, Dornoch: 01862 810267; Dental Laboratory, Dornoch: 01862 810667 We have a Village email distribution so that everyone knows what is happening – Golspie Dental Practice: 01408 633 019; Sutherland Dental Service, Lairg: 402 543 if you would like to be included please email: Julie Stevens at [email protected] tel: 07927 670 773 or Main Street, Lairg: PHARMACIES 402 374 (freephone: 0500 970 132) Carol Gilmour at [email protected] tel: 01549 441 374 Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge: 01863 760 011 Everything goes out under “blind” copy for privacy HOSPITALS / Raigmore, Inverness: 01463 704 000; visit 2.30-4.30; 6.30-8.30pm There is a local residents’ telephone directory which is available from NURSING HOMES Lawson Memorial, Golspie: 01408 633 157 & RESIDENTIAL Wick (Caithness General): 01955 605 050 the Bradbury Centre or the Post Office in Bonar Bridge. Cambusavie Wing, Golspie: 01408 633 182; Migdale, Bonar Bridge: 01863 766 211 All local events and information can be found in the -

Caithness Guide Timetable from Monday 23Rd March 2020 Until Further Notice

Caithness Guide timetable from Monday 23rd March 2020 until further notice. Service Number 80 Service Description Thurso - John O Groats Days of Operation Monday to Friday 80D 80D 80D 80 80 80 80 80 Thurso Olrig St Santander 0551 0608 0640 0830 1025 1235 1545 1735 Mount Pleasant Towerhill Road - - - - 1030 1240 1550 1740 Castletown Drill Hall 0601 0618 0650 0840 1039 1249 1559 1749 Dunnet Corner 0607 0624 0656 0846 1045 1255 1605 1755 Brough Letterbox - - - 0849 1048 1258 1608 1758 Greenvale Crossroads 0611 0628 0700 0854 1053 1303 1613 1803 Barrock - - - - 1055 1305 1616 1806 Greenvale Crossroads 0611 0628 0700 0854 1057 1307 1618 1808 Scarfskerry Baptist Church - - - 0858 1101 1311 1622 1812 Mey Post Office 0615 0632 0704 904 1107 1317 1628 1818 Gills Bay Road End - - - 0909 1113 1323 1634 1824 Canisbay - - - 0912 1117 1327 1638 1828 John o' Groats Bus Stand 0626 0643 0715 0918 1124 1334 1645 1835 Days of Operation Saturdays 80D 80 80 80 80 80 Thurso Olrig St Santander 0725 0905 1105 1305 1505 1755 Mount Pleasant Towerhill Road - 0910 1110 1310 1510 1800 Castletown Drill Hall 0735 0919 1119 1319 1519 1809 Dunnet Corner 0741 0925 1125 1325 1525 1815 Brough Letterbox - 0928 1128 1328 1528 1818 Greenvale Crossroads 0745 0933 1133 1333 1533 1823 Barrock - 0935 1135 1335 1535 1825 Greenvale Crossroads 0745 0937 1137 1337 1537 1827 Scarfskerry Baptist Church - 0941 1141 1341 1541 1831 Mey Post Office 0749 0947 1147 1347 1547 1837 Gills Bay Road End - 0953 1153 1353 1553 1843 Canisbay - 0957 1157 1357 1557 1847 John o' Groats Bus Stand - 1004 -

Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette 1837-1855

Moray & Nairn Family History Society Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette 18371837----1818181855555555 Compiled by Douglas G J Stewart No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Moray & Nairn Family History Society . Copyright © 2015 Moray & Nairn Family History Society First published 2015 Published by Moray & Nairn Family History Society 2 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements .................................................................................. 4 Marriage Notices from the Forres Gazette: 1837 ......................................................................................................................... 7 1838 ......................................................................................................................... 7 1839 ....................................................................................................................... 10 1840 ....................................................................................................................... 11 1841 ....................................................................................................................... 14 1842 ....................................................................................................................... 16 1843 ...................................................................................................................... -

Full Set of Board Papers

Assynt House Beechwood Park Inverness, IV2 3BW Telephone: 01463 717123 Fax: 01463 235189 Textphone users can contact us via Date of Issue: Typetalk: Tel 0800 959598 23 November 2012 www.nhshighland.scot.nhs.uk HIGHLAND NHS BOARD MEETING OF BOARD Tuesday 4 December 2012 at 8.30 am Board Room, Assynt House, Beechwood Park, Inverness AGENDA 1 Apologies 1.1 Declarations of Interest – Members are asked to consider whether they have an interest to declare in relation to any item on the agenda for this meeting. Any Member making a declaration of interest should indicate whether it is a financial or non-financial interest and include some information on the nature of the interest. Advice may be sought from the Board Secretary’s Office prior to the meeting taking place. 2 Minutes of Meetings of 2 October and 6 November 2012 and Action Plan (attached) (PP 1 – 24) The Board is asked to approve the Minute. 2.1 Matters Arising 3 PART 1 – REPORTS BY GOVERNANCE COMMITTEES 3.1 Argyll & Bute CHP Committee – Draft Minute of Meeting held on 31 October 2012 (attached) (PP 25 – 40) 3.2 Highland Health & Social Care Governance Committee Assurance Report of 1 November 2012 (attached) (PP 41 – 54) 3.3 Highland Health & Social Care Governance Committee – Terms of Reference for approval by the Board (attached) (PP 55 – 58) 3.4 Clinical Governance Committee – Draft Minute of Meeting of 13 November 2012 (attached) (PP 59 – 68) 3.5 Improvement Committee Assurance Report of 5 November 2012 and Balanced Scorecard (attached) (PP 69 – 80) 3.6 Area Clinical Forum – Draft Minute of Meeting held on 27 September 2012 (attached) (PP 81 – 88) 3.7 Asset Management Group – Draft Minutes of Meetings of 18 September and 23 October 2012 (attached) (PP 89 – 96) 3.8 Pharmacy Practices Committee (a) Minute of Meeting of 12 September 2012 – Gaelpharm Limited (attached) (PP 97 – 118) (b) Minute of Meeting of 30 October 2012 – Mitchells Chemist Limited (attached) (PP 119 – 134) The Board is asked to: (a) Note the Minutes. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

RIEVAULX ABBEY and ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia

RIEVAULX ABBEY AND ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia Maria JAMROZIAK Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr Wendy Childs for her continuous help and encouragement at all stages of my research. I would also like to thank other faculty members in the School of History, in particular Professor David Palliser and Dr Graham Loud for their advice. My thanks go also to Dr Mary Swan and students of the Centre for Medieval Studies who welcomed me to the thriving community of medievalists. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists in the Brotherton Library Leeds, Bodleian Library Oxford, British Library in London and Public Record Office in Kew for their assistance. Many people outside the University of Leeds discussed several aspects of Rievaulx abbey's history with me and I would like to thank particularly Dr Janet Burton, Dr David Crouch, Professor Marsha Dutton, Professor Peter Fergusson, Dr Brian Golding, Professor Nancy Partner, Dr Benjamin Thompson and Dr David Postles as well as numerous participants of the conferences at Leeds, Canterbury, Glasgow, Nottingham and Kalamazoo, who offered their ideas and suggestions. I would like to thank my friends, Gina Hill who kindly helped me with questions about English language, Philip Shaw who helped me to draw the maps and Jacek Wallusch who helped me to create the graphs and tables. -

History of the Mathesons, with Genealogies of the Various Branches

*>* '-ii.-M WBBm ^H I THE ifiTO] iY and Genealogy OF THE , . I * . I Eli O KJ v*.*^ ^H ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, E.S.A. SCOT. / IXo. National Library of Scotland iniiiir l B000244182* x>N0< jlibsary;^ A HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS, WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE VARIOUS BRANCHES. BY ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A., Scut., Editor of the " Celtic Magazine ;" author of " The History of the Mackenzie.? ;" " The History of the Macdonalds and Lords of tlie Isles ;" &c, Sec. O CHIAN. INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCLXXXH. PRINTED AT THE ADVERTISER OFFICE, II BANK STREET, INVERNESS. INSCRIBED LADY MATHESON OF THE LEWS, AS A TRIBUTE OF RESPECT FOR HERSELF, AND TO THE MEMORY OF HER LATE HUSBAND, SIR JAMES MATHESON, BART., THE AUTHOR. CONTENTS. ORIGIN—AND BENNETSFIELD MATHESONS 1-34 THE MATHESONS OF LOCHALSH AND ARDROSS 35-48 THE MATHESONS OF SHINESS, ACHANY, AND THE LEWS 49-54 THE IOMAIRE MATHESONS 55-58 SIR JAMES MATHESON OF THE LEWS, BARONET 59-72 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/historyofmathamOOmack LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS. Aitken, Dr, F.S.A., Scot., Inverness Allan, William, Esq., Sunderland Anderson, James, Esq., Hilton, Inverness Best, Mrs Vans, Belgium—(3 copies) Blair, Sheriff, Inverness Burns, William, Esq., Solicitor, Inverness Campbell, Geo. J., Esq., Solicitor, Inverness Carruthers, Robert, Esq., of the Inverness Courier Chisholm, Archd. A., Esq., Procurator-Fiscal, Lochmaddy Chisholm, Colin, Namur Cottage, Inverness Chisholm, The, Erchless Castle Clarke, James, Esq., Solicitor, Inverness Cran, John, Esq., F.S.A., Scot, Bunchrew Croal, Thos. A., Esq., F.S.A., Scot., Edinburgh Davidson, John, Esq., Merchant, Inverness Finlayson, Roderick, Esq., Nairn Foster, W. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump)