History of Baltimore City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE VILLAGE at FALLSWAY MULTIFAMILY DEVELOPMENT in an OPPORTUNITY ZONE BALTIMORE, MARYLAND the Village at Fallsway

THE VILLAGE AT FALLSWAY MULTIFAMILY DEVELOPMENT IN AN OPPORTUNITY ZONE BALTIMORE, MARYLAND The Village at Fallsway THIS CONFIDENTIAL OFFERING MEMORANDUM (“Offering Memorandum”) is being furnished to the recipient (the “Recipient”) solely for the Recipient’s own limited use in considering whether to provide financing for The Village at Fallsway located at 300-320 North Front Street, 300-312 North High Street, and 300 Fallsway, Baltimore, MD (the “Property”), on behalf of Airo Capital Management (the “Sponsor”). This confidential information does not purport to be all-inclusive nor does it purport to contain all the information that a prospective investor may desire. Neither Avison Young, the Sponsor nor any of their respective partners, managers, officers, employees or agents makes any representation, guarantee or warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of this Offering Memorandum or any of its contents and no legal liability is assumed or shall be implied with respect thereto. The Recipient agrees that: (a) the Offering Memorandum and its contents are confidential information, except for such information contained in the Offering Memorandum that is a matter of public record; (b) the Recipient and the Recipient’s employees, agents, and consultants (collectively, the “need to know parties”) will hold and treat the Offering Memorandum in the strictest of confidence, and the Recipient and the need to know parties will not, directly or indirectly, disclose or permit anyone else to disclose its contents to any other person, firm, or entity without the prior written authorization of the Sponsor; and, (c) the Recipient and the need to know parties will not use, or permit to be used, this Offering Memorandum or its contents in any fashion or manner detrimental to the interest of the Sponsor or for any purpose other than use in considering whether to invest into the Property. -

Federal Relief Programs in the 19Th Century: a Reassessment

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 19 Issue 3 September Article 8 September 1992 Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment Frank M. Loewenberg Bar-Ilan University, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Social History Commons, Social Work Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Loewenberg, Frank M. (1992) "Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol19/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment FRANK M. LOEWENBERG Bar-Ilan University Israel School of Social Work The American model of the welfare state, incomplete as it may be, was not plucked out of thin air by the architects of the New Deal in the 1930s. Instead it is the product and logical evolution of a long histori- cal process. 19th century federal relief programsfor various population groups, including veterans, native Americans, merchant sailors, eman- cipated slaves, and residents of the District of Columbia, are examined in order to help better understand contemporary welfare developments. Many have argued that the federal government was not in- volved in social welfare matters prior to the 1930s - aside from two or three exceptions, such as the establishment of the Freed- man's Bureau in the years after the Civil War and the passage of various federal immigration laws that attempted to stem the flood of immigrants in the 1880s and 1890s. -

The Gallery / Harborplace 200 E

THE GALLERY / HARBORPLACE 200 E. Pratt Street / 111 S. Calvert Street Baltimore, Maryland AREA AMENITIES FLEXIBLE OFFICE SPACE PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS Outstanding views overlooking Baltimore’s THE GALLERY / famed Inner Harbor Parking garage (1,190 cars) with 24/7 access HARBORPLACE New fitness center FREE to all tenants 200 E. Pratt Street 600-room Renaissance Harborplace Hotel interconnected 111 S. Calvert Street Lobby guard on duty and fully automated New 30,000 square foot high-end “Spaces” co-working facility Baltimore, Maryland Retail amenities including new full-service restaurant COMING SOON! -- Dunkin'® HARBOR VIEW MATTHEW SEWARD BRONWYN LEGETTE Senior Director Director +1 410 347 7549 +1 410 347 7565 [email protected] [email protected] One East Pratt Street, Suite 700 | Baltimore, MD 21202 Main +1 410 752 4285 | Fax +1 576 9031 cushmanwakefield.com ©2019 Cushman & Wakefield. All rights reserved. The information contained in this communication is strictly confidential. This information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but has not been verified. No warranty or representation, express or implied, is made as to the condition of the property (or properties) referenced herein or as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, and same is submitted subject to errors, omissions, change of price, rental or other conditions, withdraw- al without notice, and to any special listing conditions imposed by the property owner(s). Any projections, opinions or estimates are subject -

Fort Mchenry - "Our Country" Bicentennial Festivities, Baltimore, MD, 7/4/75 (2)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 67, folder “Fort McHenry - "Our Country" Bicentennial Festivities, Baltimore, MD, 7/4/75 (2)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON '!0: Jack Marsh FROM: PAUL THEIS a>f Although belatedly, attached is some material on Ft. McHenry which our research office just sent in ••• and which may be helpful re the July 4th speech. Digitized from Box 67 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library :\iE\10 R.-\~ D l. \I THE \\'HITE HOI.SE \L\Sllli"GTO:'\ June 23, 1975 TO: PAUL 'IHEIS FROM: LYNDA DURFEE RE: FT. McHENRY FOURTH OF JULY CEREMONY Attached is my pre-advance report for the day's activities. f l I I / I FORT 1:vlc HENRY - July 4, 1975 Progran1 The program of events at Fort McHenry consists of two parts, with the President participating in the second: 11 Part I: "By the Dawn's Early Light • This is put on by the Baltimore Bicentennial Committee, under the direction of Walter S. -

Baltimore, Maryland

National Aeronautics and Space Administration SUSGS Goddard Space Flight Center LANDSAT 7 science for a chanuinu world Baltimore, Maryland Baltimore Zoo '-~ootballStadium Lake Montebello -Patterson Park Fort McHenry A Druid Hill Park Lake -Camden Yards Inner Harbor - Herring Run Park National Aeronautics and Space Administration ZIUSGS Goddard Space Flight Center Landsat 7 science for a changing world About this Image For The Classroom This false color image of the Baltimore, MD metropolitan area was taken infrared band. The instrument images the Earth in 115 mile (183 The use of satellites, such as Landsat, provides the opportunity to study on the morning of May 28, 1999, from the recently launched Landsat 7 kilometer) swaths. the earth from above. From this unique perspective we can collect data spacecraft. It is the first cloud-free Landsat 7 image of this region, History about earth processes and changes that may be difficult or impossible to acquired prior to the satellite being positioned in its operational orbit. The The first Landsat, originally called the Earth Resources Technology collect on the surface. For example, if you want to map forest cover, image was created by using ETM+ bands 4,3,2 (30m) merged with the 15- Satellite (ERTS-I), was developed and launched by NASA in July 1972. you do not need nor want to see each tree. In this activity, students will meter panchromatic band. Using this band combination trees and grass are Subsequent launches occurred in January 1975 and March 1978. explore the idea that being closer is not necessarily better or more red, developed areas are light bluellight green and water is black. -

Gunpowder River

Table of Contents 1. Polluted Runoff in Baltimore County 2. Map of Baltimore County – Percentage of Hard Surfaces 3. Baltimore County 2014 Polluted Runoff Projects 4. Fact Sheet – Baltimore County has a Problem 5. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Back River 6. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Gunpowder River 7. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Middle River 8. Sources of Pollution in Baltimore County – Patapsco River 9. FAQs – Polluted Runoff and Fees POLLUTED RUNOFF IN BALTIMORE COUNTY Baltimore County contains the headwaters for many of the streams and tributaries feeding into the Patapsco River, one of the major rivers of the Chesapeake Bay. These tributaries include Bodkin Creek, Jones Falls, Gwynns Falls, Patapsco River Lower North Branch, Liberty Reservoir and South Branch Patapsco. Baltimore County is also home to the Gunpowder River, Middle River, and the Back River. Unfortunately, all of these streams and rivers are polluted by nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment and are considered “impaired” by the Maryland Department of the Environment, meaning the water quality is too low to support the water’s intended use. One major contributor to that pollution and impairment is polluted runoff. Polluted runoff contaminates our local rivers and streams and threatens local drinking water. Water running off of roofs, driveways, lawns and parking lots picks up trash, motor oil, grease, excess lawn fertilizers, pesticides, dog waste and other pollutants and washes them into the streams and rivers flowing through our communities. This pollution causes a multitude of problems, including toxic algae blooms, harmful bacteria, extensive dead zones, reduced dissolved oxygen, and unsightly trash clusters. -

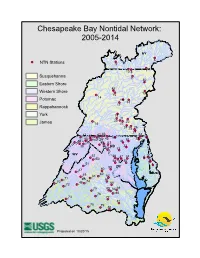

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014 NY 6 NTN Stations 9 7 10 8 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 Western Shore 12 15 14 Potomac 16 13 17 Rappahannock York 19 21 20 23 James 18 22 24 25 26 27 41 43 84 37 86 5 55 29 85 40 42 45 30 28 36 39 44 53 31 38 46 MD 32 54 33 WV 52 56 87 34 4 3 50 2 58 57 35 51 1 59 DC 47 60 62 DE 49 61 63 71 VA 67 70 48 74 68 72 75 65 64 69 76 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: All Stations NTN Stations 91 NY 6 NTN New Stations 9 10 8 7 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 12 Western Shore 92 15 16 Potomac 14 PA 13 Rappahannock 17 93 19 95 96 York 94 23 20 97 James 18 98 100 21 27 22 26 101 107 24 25 102 108 84 86 42 43 45 55 99 85 30 103 28 5 37 109 57 31 39 40 111 29 90 36 53 38 41 105 32 44 54 104 MD 106 WV 110 52 112 56 33 87 3 50 46 115 89 34 DC 4 51 2 59 58 114 47 60 35 1 DE 49 61 62 63 88 71 74 48 67 68 70 72 117 75 VA 64 69 116 76 65 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Table 1. -

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19Ctheatrevisuality

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19ctheatrevisuality Henry Emden, City of Coral scene, Drury Lane, pantomime set model, 1903 © V&A Conference at the University of Warwick 27—29 June 2019 Organised as part of the AHRC project, Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century, Jim Davis, Kate Holmes, Kate Newey, Patricia Smyth Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century Funded by the AHRC, this collaborative research project examines theatre spectacle and spectatorship in the nineteenth century by considering it in relation to the emergence of a wider trans-medial popular visual culture in this period. Responding to audience demand, theatres used sophisticated, innovative technologies to create a range of spectacular effects, from convincing evocations of real places to visions of the fantastical and the supernatural. The project looks at theatrical spectacle in relation to a more general explosion of imagery in this period, which included not only ‘high’ art such as painting, but also new forms such as the illustrated press and optical entertainments like panoramas, dioramas, and magic lantern shows. The range and popularity of these new forms attests to the centrality of visuality in this period. Indeed, scholars have argued that the nineteenth century witnessed a widespread transformation of conceptions of vision and subjectivity. The project draws on these debates to consider how far a popular, commercial form like spectacular theatre can be seen as a site of experimentation and as a crucible for an emergent mode of modern spectatorship. This project brings together Jim Davis and Patricia Smyth from the University of Warwick and Kate Newey and Kate Holmes from the University of Exeter. -

All Hazards Plan for Baltimore City

All-Hazards Plan for Baltimore City: A Master Plan to Mitigate Natural Hazards Prepared for the City of Baltimore by the City of Baltimore Department of Planning Adopted by the Baltimore City Planning Commission April 20, 2006 v.3 Otis Rolley, III Mayor Martin Director O’Malley Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Plan Contents....................................................................................................................1 About the City of Baltimore ...............................................................................................3 Chapter Two: Natural Hazards in Baltimore City .....................................................................5 Flood Hazard Profile .........................................................................................................7 Hurricane Hazard Profile.................................................................................................11 Severe Thunderstorm Hazard Profile..............................................................................14 Winter Storm Hazard Profile ...........................................................................................17 Extreme Heat Hazard Profile ..........................................................................................19 Drought Hazard Profile....................................................................................................20 Earthquake and Land Movement -

Baltimore Neighborhoods Bolton Hill 1

Greetings, You are receiving this list because you have previously purchased or expressed interest in collecting books about Maryland and/or Baltimore. Orders may be placed in person, by phone, e-mail, or through our website at www.kelmscottbookshop.com. Our hours are Monday - Friday from 10 am - 6 pm. We accept payment via cash, major credit card, PayPal, check, and money order. Shipping will be $5 for media mail, $12 for priority mail, or $15 for Fedex Ground. There will be a $2 charge for each additional mailed title. Thank you for reviewing our list. BALTIMORE & MARYLAND LIST 2015 Baltimore Neighborhoods Bolton Hill 1. Frank R. Shivers, Jr. Bolton Hill: Baltimore Classic. F.R. Shivers, Jr., 1978. SCARCE. Very good in brown paper wrappers with blue title to front wrapper. Minor rubbing to wrappers Foxing to inside of rear wrapper. Else is clean and bright. Filled with photographic illustrations. 49 pages. (#23966) $25 Brooklyn-Curtis Bay 2. A History of Brooklyn-Curtis Bay, 1776-1976. Baltimore: The Brooklyn-Curtis Bay Historical Committee, 1976. SCARCE. INSCRIBED by Hubert McCormick, the General Chairman of the Curtis-Bay Historical Committee. Very good in white side stapled illustrated paper wrappers with red title to front cover. Interior is clean and bright with photographic illustrations throughout. 217 pages. (#24052) $95 Canton 3. Rukert, Norman G. Historic Canton: Baltimore’s Industrial Heartland ... and Its People. Baltimore: Bodine and Associates, Inc., 1978. INSCRIBED TWICE BY THE AUTHOR. Near fine in brown cloth covered boards with gilt title to spine. Author’s inscriptions to front free end page and half title page. -

19-1189 BP PLC V. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus BP P. L. C. ET AL. v. MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF BALTIMORE CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT No. 19–1189. Argued January 19, 2021—Decided May 17, 2021 Baltimore’s Mayor and City Council (collectively City) sued various en- ergy companies in Maryland state court alleging that the companies concealed the environmental impacts of the fossil fuels they promoted. The defendant companies removed the case to federal court invoking a number of grounds for federal jurisdiction, including the federal officer removal statute, 28 U. S. C. §1442. The City argued that none of the defendants’ various grounds for removal justified retaining federal ju- risdiction, and the district court agreed, issuing an order remanding the case back to state court. Although an order remanding a case to state court is ordinarily unreviewable on appeal, Congress has deter- mined that appellate review is available for those orders “remanding a case to the State court from which it was removed pursuant to section 1442 or 1443 of [Title 28].” §1447(d). The Fourth Circuit read this provision to authorize appellate review only for the part of a remand order deciding the §1442 or §1443 removal ground. -

Port Services Guide for Visiting Ships to Baltimore

PORT SERVICES GUIDE Port Services Guide For Visiting Ships to Baltimore Created by Sail Baltimore Page 1 of 17 PORT SERVICES GUIDE IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS IN BALTIMORE POLICE, FIRE & MEDICAL EMERGENCIES 911 Police, Fire & Medical Non-Emergencies 311 Baltimore City Police Information 410-396-2525 Inner Harbor Police (non-emergency) 410-396-2149 Southeast District - Fells Point (non-emergency) 410-396-2422 Sgt. Kenneth Williams Marine Police 410-396-2325/2326 Jeffrey Taylor, [email protected] 410-421-3575 Scuba dive team (for security purposes) 443-938-3122 Sgt. Kurt Roepke 410-365-4366 Baltimore City Dockmaster – Bijan Davis 410-396-3174 (Inner Harbor & Fells Point) VHF Ch. 68 US Navy Operational Support Center - Fort McHenry 410-752-4561 Commander John B. Downes 410-779-6880 (ofc) 443-253-5092 (cell) Ship Liaison Alana Pomilia 410-779-6877 (ofc) US Coast Guard Sector Baltimore - Port Captain 410-576-2564 Captain Lonnie Harrison - Sector Commander Commander Bright – Vessel Movement 410-576-2619 Search & Rescue Emergency 1-800-418-7314 General Information 410-789-1600 Maryland Port Administration, Terminal Operations 410-633-1077 Maryland Natural Resources Police 410-260-8888 Customs & Border Protection 410-962-2329 410-962-8138 Immigration 410-962-8158 Sail Baltimore 410-522-7300 Laura Stevenson, Executive Director 443-721-0595 (cell) Michael McGeady, President 410-942-2752 (cell) Nan Nawrocki, Vice President 410-458-7489 (cell) Carolyn Brownley, Event Assistant 410-842-7319 (cell) Page 2 of 17 PORT SERVICES GUIDE PHONE