The Tianxia System and the Search for a Common Ground in the Comparative Ethics of War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Right Concept, Wrong Country: Tianming and Tianxia in International Relations Originally Published At

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Right Concept, Wrong Country: Tianming and Tianxia in International Relations Originally published at: http://www.asianreviewofbooks.com/pages/?ID=2500 by Salvatore Babones 14 January 2016 The Mandate of Heaven and The Great Ming Code (new ed.) Jiang Yonglin University of Washington Press, September 2015 Ancient Chinese Thought, Modern Chinese Power (new ed.) Yan Xuetong, Daniel A. Bell (ed), Sun Zhe (ed), Edmund Ryden (trans) Princeton University Press, August 2013 The Tianxia System: An Introduction to the Philosophy of World Institution (in Chinese) Zhao Tingyang China Renmin University Press, 2011 A rising “Chinese School” of international relations may have more to say about the United States than about China itself. Today’s China is a country of great contradictions—and great ironies. In the political sphere, the combined net worth the members of its National “People’s” Congress is over US$90 billion. In the economic sphere, nearly all of the major companies traded on the Shanghai stock exchange are majority owned by the government. And in the cultural sphere, almost every city in this Communist- ruled country has a brand new statue of Confucius. Confucius is back. Casual observers of China may not know that Confucius had ever left. But Mao identified Confucianism with “imperialism and the feudal class”. During the Cultural Revolution students were told to reject the Four Olds: old culture, old customs, old habits, and old ideas. And “old” in China means Confucius. Ancient books were burned. -

Mohist Theoretic System: the Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections with the Universal Values and Global Sustainability

Cultural and Religious Studies, March 2020, Vol. 8, No. 3, 178-186 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.03.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Mohist Theoretic System: The Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections With the Universal Values and Global Sustainability SONG Jinzhou East China Normal University, Shanghai, China Mohism was established in the Warring State period for two centuries and half. It is the third biggest schools following Confucianism and Daoism. Mozi (468 B.C.-376 B.C.) was the first major intellectual rivalry to Confucianism and he was taken as the second biggest philosophy in his times. However, Mohism is seldom studied during more than 2,000 years from Han dynasty to the middle Qing dynasty due to his opposition claims to the dominant Confucian ideology. In this article, the author tries to illustrate the three potential functions of Mohism: First, the critical/revision function of dominant Confucianism ethics which has DNA functions of Chinese culture even in current China; second, the interconnections with the universal values of the world; third, the biological constructive function for global sustainability. Mohist had the fame of one of two well-known philosophers of his times, Confucian and Mohist. His ideas had a decisive influence upon the early Chinese thinkers while his visions of meritocracy and the public good helps shape the political philosophies and policy decisions till Qin and Han (202 B.C.-220 C.E.) dynasties. Sun Yet-sen (1902) adopted Mohist concepts “to take the world as one community” (tian xia wei gong) as the rationale of his democratic theory and he highly appraised Mohist concepts of equity and “impartial love” (jian ai). -

Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy

Readings In Classical Chinese Philosophy edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe University of Michigan and Bryan W. Van Norden Vassar College Seven Bridges Press 135 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10010-7101 Copyright © 2001 by Seven Bridges Press, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Publisher: Ted Bolen Managing Editor: Katharine Miller Composition: Rachel Hegarty Cover design: Stefan Killen Design Printing and Binding: Victor Graphics, Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Readings in classical Chinese philosophy / edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe, Bryan W. Van Norden. p. cm. ISBN 1-889119-09-1 1. Philosophy, Chinese--To 221 B.C. I. Ivanhoe, P. J. II. Van Norden, Bryan W. (Bryan William) B126 .R43 2000 181'.11--dc21 00-010826 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CHAPTER TWO Mozi Introduction Mozi \!, “Master Mo,” (c. 480–390 B.C.E.) founded what came to be known as the Mojia “Mohist School” of philosophy and is the figure around whom the text known as the Mozi was formed. His proper name is Mo Di \]. Mozi is arguably the first true philosopher of China known to us. He developed systematic analyses and criticisms of his opponents’ posi- tions and presented an array of arguments in support of his own philo- sophical views. His interest and faith in argumentation led him and his later followers to study the forms and methods of philosophical debate, and their work contributed significantly to the development of early Chinese philosophy. -

Mozi 31: Explaining Ghosts, Again Roel Sterckx* One Prominent Feature

MOZI 31: EXPLAINING GHOSTS, AGAIN Roel Sterckx* One prominent feature associated with Mozi (Mo Di 墨翟; ca. 479–381 BCE) and Mohism in scholarship of early Chinese thought is his so-called unwavering belief in ghosts and spirits. Mozi is often presented as a Chi- nese theist who stands out in a landscape otherwise dominated by this- worldly Ru 儒 (“classicists” or “Confucians”).1 Mohists are said to operate in a world clad in theological simplicity, one that perpetuates folk reli- gious practices that were alive among the lower classes of Warring States society: they believe in a purely utilitarian spirit world, they advocate the use of simple do-ut-des sacrifices, and they condemn the use of excessive funerary rituals and music associated with Ru elites. As a consequence, it is alleged, unlike the Ru, Mohist religion is purely based on the idea that one should seek to appease the spirit world or invoke its blessings, and not on the moral cultivation of individuals or communities. This sentiment is reflected, for instance, in the following statement by David Nivison: Confucius treasures the rites for their value in cultivating virtue (while virtually ignoring their religious origin). Mozi sees ritual, and the music associated with it, as wasteful, is exasperated with Confucians for valuing them, and seems to have no conception of moral self-cultivation whatever. Further, Mozi’s ethics is a “command ethic,” and he thinks that religion, in the bald sense of making offerings to spirits and doing the things they want, is of first importance: it is the “will” of Heaven and the spirits that we adopt the system he preaches, and they will reward us if we do adopt it. -

Changing Views of Tianxia in Pre-Imperial Discourse*

Changing views of tianxia in pre-imperial discourse* Yuri Pines (Jerusalem) Half a century ago Joseph Levenson defined the traditional concept of tianxia 天下 (“world”, “All under Heaven”) as referring primarily to a cultural realm, being “a regime of value”, as opposed to a political unit, guo 國, “a state”.1 The implication is clear: tianxia was a supra-political unit, larger than the manageable Zhongguo 中國, “the Central States”, i.e. the Chinese empire. Authors of modern Chinese dictionaries, such as Cihai 辭海 or Hanyu da cidian 漢語大詞典, disagree with Levenson: they suggest that tianxia was a political unit basically identical with Zhongguo, while its meaning as “the larger world” was secondary. The difference is more than purely semantic; for Levenson, at least, the distinction between tianxia and guo had far-reaching implications on China’s problematic entrance into the modern world of nation-states.2 Levenson’s study relied primarily on late imperial discourse. In this article I will complement his research by tracing the origins of the term tianxia and its earliest usage. I shall try to verify first whether Levenson’s juxtaposition of cultural and political meanings of this term is traceable to pre- imperial texts, and second, what were the limits of pre-imperial tianxia and whether or not it was confined to the Central States, i.e. the Zhou 周 realm. A preliminary warning which has to be made is that unlike many other terms of political and philosophical discourse, the precise meaning of the term tianxia was never scrutinized by pre-imperial statesmen and thinkers, and its usage remained quite loose, reminiscent of the modern usage of such terms as “nation”, “humanity” or “the world” by politicians and journalists, rather than the rigid lexi- con of philosophical discourse.3 A single text, and sometimes a single passage, could refer to tianxia in two or more different, even contradictory, ways. -

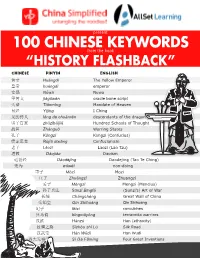

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

Warring States and Harmonized Nations: Tianxia Theory As a World Political Argument Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2020, 205 P

JYU DISSERTATIONS 247 Matti Puranen Warring States and Harmonized Nations Tianxia Theory as a World Political Argument JYU DISSERTATIONS 247 Matti Puranen Warring States and Harmonized Nations Tianxia Theory as a World Political Argument Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi heinäkuun 17. päivänä 2020 kello 9. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, on July 17, 2020 at 9 o’clock a.m.. JYVÄSKYLÄ 2020 Editors Olli-Pekka Moisio Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä Timo Hautala Open Science Centre, University of Jyväskylä Copyright © 2020, by University of Jyväskylä Permanent link to this publication: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-8218-8 ISBN 978-951-39-8218-8 (PDF) URN:ISBN:978-951-39-8218-8 ISSN 2489-9003 ABSTRACT Puranen, Matti Warring states and harmonized nations: Tianxia theory as a world political argument Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2020, 205 p. (JYU Dissertations ISSN 2489-9003; 247) ISBN 978-951-39-8218-8 The purpose of this study is to examine Chinese foreign policy by analyzing Chinese visions and arguments on the nature of world politics. The study focuses on Chinese academic discussions, which attempt to develop a ’Chinese theory of international politics’, and especially on the so called ’tianxia theory’ (天下论, tianxia lun), which is one of the most influential initiatives within these discussions. Tianxia theorists study imperial China’s traditional system of foreign relations and claim that the current international order, which is based on competing nation states, should be replaced with some kind of world government that would oversee the good of the whole planet. -

China´S Cultural Fundamentals Behind Current Foreign Policy Journal Views: Heritage of Old Thinking Habits in Chinese Modern Thoughts

Lajčiak, M. (2017). China´s cultural fundamentals behind current foreign policy Journal views: Heritage of old thinking habits in Chinese modern thoughts. Journal of of International International Studies, 10(2), 9-27. doi:10.14254/2071-8330.2017/10-2/1 Studies © Foundation China´s cultural fundamentals behind of International current foreign policy views: Heritage of Studies, 2017 © CSR, 2017 old thinking habits in Chinese modern Scientific Papers thoughts Milan Lajčiak Ambassador of the Slovak Republic to the Republic of Korea Slovak Embassy in Seoul, South Korea Email: [email protected] Abstract. Different philosophical frameworks between China and the West found Received: December, 2016 their reflection in diverging concepts of managing relations with the outside 1st Revision: world. China focused more on circumstances, managing situation and preventing February, 2017 conflicts, the West was resolution oriented, aimed at fighting opponents and Accepted: March, 2017 looking for victory in conflicts. China has introduced the idea of harmony - hierarchy world, while the West, on the opposite, tends to freedom-conflict DOI: patterns of relations. On China’s side, thinking habits and old thought paradigms 10.14254/2071- of statecraft are until now deeply ingrained in mentality, thus shaping China´s 8330.2017/10-2/1 policy today. Understanding the background of Chinese traditional thinking modes and mind heritage helps better understanding of China´s rise in global affairs as well as of Sino-American relations as the key element in a search for global leadership. Keywords: China, West, thinking habits, foreign policy concepts, China rise, Sino- American relations. JEL Classification: F5, P5, Z1 1. -

View Sample Pages

This Book Is Dedicated to the Memory of John Knoblock 未敗墨子道 雖然歌而非歌哭而非哭樂而非樂 是果類乎 I would not fault the Way of Master Mo. And yet if you sang he condemned singing, if you cried he condemned crying, and if you made music he condemned music. What sort was he after all? —Zhuangzi, “In the World” A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. Although the institute is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibility for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. The China Research Monograph series is one of the several publication series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunction with its constituent units. The others include the Japan Research Monograph series, the Korea Research Monograph series, and the Research Papers and Policy Studies series. Send correspondence and manuscripts to Katherine Lawn Chouta, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies 2223 Fulton Street, 6th Floor Berkeley, CA 94720-2318 [email protected] Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mo, Di, fl. 400 B.C. [Mozi. English. Selections] Mozi : a study and translation of the ethical and political writings / by John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel. pages cm. -- (China research monograph ; 68) English and Chinese. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55729-103-9 (alk. paper) 1. Mo, Di, fl. 400 B.C. Mozi. I. Knoblock, John, translator, writer of added commentary. II. Riegel, Jeffrey K., 1945- translator, writer of added commentary. III. Title. B128.M79E5 2013 181'.115--dc23 2013001574 Copyright © 2013 by the Regents of the University of California. -

Etiquette and Order: the Tributary System in the Qing Dynasty

2020 International Conference on Economics, Education and Social Research (ICEESR 2020) Etiquette and Order: the Tributary System in the Qing Dynasty Peng Gao Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou, Gansu, 730070, China Keywords: Qing dynasty, Tributary system, Central dynasty, Vassal state, Tianxia worldview Abstract: Following the traditions of the Ming Dynasty, the Qing Dynasty built a tributary system to seek its own security and border stability. This system of maintaining the traditional order in East Asia and linking various vassals gradually became normalization during its operation, which established a special agency responsible for the ministry of minority affairs and the Ministry of Rites to manage the northwest vassals and the southeast vassals and their tributary activities. The Qing tributary system had distinctive features, and established clear rights and obligations and hierarchical order between the Central Dynasty and the vassals around the Qing Dynasty. With the decline of power in the late Qing Dynasty, the tributary system gradually disintegrated, but its historical practice still has implications for the present. 1. Introduction The Qing Dynasty established by the Manchus was the last dynasty of China's feudal society. It established a vast territory by conquering it by force. As a centralized state with many nationalities, which adhered to the traditional Chinese Tianxia worldview, that is, as the central state of the world, all countries that wished to develop relations with it must accept the status of vassals. This kind of interactive relationship between the heavenly kingdom and many vassals maintained by conferring the title and tributary activities is called the tributary system. From the content point of view, it included the pilgrimage to the central dynasty, the tribute to the central dynasty, and the central dynasty's entitlement to the vassals; from the scope, it was an important means for the central dynasty to handle national relations and foreign relations. -

The Chinese Meaning of Just War and Its Impact on the Foreign Policy of the People’S Republic of China

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics GIGA Research Programme: Violence, Power and Security ___________________________ The Chinese Meaning of Just War and Its Impact on the Foreign Policy of the People’s Republic of China Nadine Godehardt N° 88 September 2008 www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers GIGA WP 88/2008 GIGA Working Papers Edited by the GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien The Working Paper Series serves to disseminate the research results of work in progress prior to publication in order to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. Inclusion of a paper in the Working Paper Series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. Copyright remains with the authors. When Working Papers are eventually accepted by or published in a journal or book, the correct citation reference and, if possible, the corresponding link will then be included in the Working Papers website at <www.giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers>. GIGA research unit responsible for this issue: Research Programme: “Violence, Power and Security” Editor of the GIGA Working Paper Series: Martin Beck <[email protected]> Copyright for this issue: © Nadine Godehardt English copy editor: Melissa Nelson Editorial assistant and production: Vera Rathje All GIGA Working Papers are available online and free of charge on the website <www. giga-hamburg.de/workingpapers>. -

The Tianxia System: World Order in a Chinese Utopia

GLOBAL ASIA Book Review this spirit, I here review the infl uential works of Zhao Tingyang, a distinguished academic at the The Tianxia System: Institute of Philosophy at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing. World Order In Although Zhao had already established himself as a philosopher before 2005, the publication of his book Tianxia Tixi that year made him a star in A Chinese Utopia China’s intellectual circles, helping to extend his Reviewed By Feng Zhang infl uence beyond the confi nes of philosophy into the realm of international relations. Four years later, he published a second volume further de- Tianxia Tixi: Shijie veloping his tianxia (literally, “all-under-heav- Zhidu Zhexue Daolun en”) theory while offering a more comprehen- [The Tianxia System: sive outline of his own political philosophy. His An Introduction to philosophical theory of international relations the Philosophy of has had a huge impact on China’s community of a World Institution] international relations scholars, stirring up ex- By Zhao Tingyang citement as well as curiosity. This is due, in part, Nanjing: Jiangsu Jiaoyu Chubanshe, to the fact that Chinese scholars in this fi eld have 2005, 160 pages not been able to produce a theory as sophisticated as his, even though this has been on their agenda Huai Shijie Yanjiu: for some time. Zuowei Diyi Zhexue Not being a philosopher myself, I shall concen- de Zhengzhi Zhexue trate on those parts of Zhao’s writings that direct- [Investigations of the ly pertain to international relations, which are Bad World: Political most of his 2005 book and most of Chapter 4 in Philosophy as the his 2009 book.