Hip-Hop in Hollywood: Encounter, Community, Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Product Catalog

2020 PRODUCT CATALOG FREE DELIVERY* INSTALLATION AVAILABLE BEST WARRANTY LOCAL SAME DAY WITHIN 48 HOURS IN THE INDUSTRY *WITHIN LOCAL DELIVERY AREA, SEE PAGE 76 FOR DETAILS. CONTENTS RAFTS 3 Polyethylene Swim Raft 4 Aluminum Frame Swim Raft 5 DECKING OPTIONS 8 DOCKS 13 Infinity RS4 14 Infinity RS4 Curve 19 Infinity RS7 22 Infinity Track™ QuickSteps 27 Infinity Track™ Hinges 29 Gangways 30 Infinity TS9 32 PolyDock 36 Floating FTS9 40 Shoreport™ 44 ShoreMaster Flotation 45 RhinoFloat 46 INFINITY TRACK™ 48 Infinity Track™ Dock Accessories 49 ALUMINUM LIFTS 54 Vertical & Cantilever Lifts 55 Pontoon & Tri-toon Lifts 57 Hydraulic Lift 61 Heavy Capacity Lift 63 YOUR PASSION FUELS OURS. PWC Lifts 64 CANOPIES 66 Canopy Covers 68 Discover the ShoreMaster difference. Traditional Canopy 69 Hip Roof Canopy 71 For nearly three decades ShoreMaster has offered the broadest line of waterfront BOAT LIFT POWER UNITS 74 equipment in the industry through Hammond Lumber Company. There is no one style Lift Mate™ 74 Lift Boss™ 74 of dock or lift that fits every situation. DELIVERY FEES 76 SHOREMASTER’S LIMITED WARRANTY 77 SPECIFICATIONS 79 Let Hammond Lumber Company match you with the right equipment for your waterfront. ACCESSORIES 83 We pride ourselves on providing safe, dependable products that are easy to use and DESIGN YOUR DOCK 85 are as beautiful as your lake home. Our docks are built with quality aluminum that is maintenance free so you can relax and enjoy your time at the lake for years to come. *All prices may be subject to change. HAMMONDLUMBER.COM | 2 POLYETHYLENE SWIM RAFT benefits SIZE 7.5 foot by 9.5 foot nonskid RAFTS deck surface SAFETY FIRST One piece, all poly swim raft with reflectors on each corner provide additional safety. -

Polka Sax Man More Salute to Steel 3 from the TPN Archives Donnie Wavra July 2006: 40Th National Polka by Gary E

Texas Polka News - March 2016 Volume 28 | Isssue 2 INSIDE Texas Polka News THIS ISSUE 2 Bohemian Princess Diary Theresa Cernoch Parker IPA fundraiser was mega success! Welcome new advertiser Janak's Country Market. Our first Spring/ Summer Fest Guide 3 Editor’s Log Gary E. McKee Polka Sax Man More Salute to Steel 3 From the TPN Archives Donnie Wavra July 2006: 40th National Polka By Gary E. McKee Festival Story on Page 4 4-5 Featured Story Polka Sax Man 6-7 Czech Folk Songs Program; Ode to the Songwriter 8-9 Steel Story Continued 10 Festival & Dance Notes 12-15 Dances, Festivals, Events, Live Music 16-17 News PoLK of A Report, Mike's Texas Polkas Update, Czech Heritage Tours Special Trip, Alex Says #Pep It Up 18-19 IPA Fundraiser Photos 20 In Memoriam 21 More Event Photos! 22-23 More Festival & Dance Notes 24 Polka Smiles Sponsored by Hruska's Spring/SummerLook for the Fest 1st Annual Guide Page 2 Texas Polka News - March 2016 polkabeat.com Polka On Store to order Bohemian Princess yours today!) Texas Polka News Staff Earline Okruhlik and Michael Diary Visoski also helped with set up, Theresa Cernoch Parker, Publisher checked people in, and did whatever Gary E. McKee, Editor/Photo Journalist was asked of them. Valina Polka was Jeff Brosch, Artist/Graphic Designer Contributors: effervescent as always helping decorate the tables and serving as a great hostess Julie Ardery Mark Hiebert Alec Seegers Louise Barcak Julie Matus Will Seegers leading people to their tables. Vernell Bill Bishop Earline Berger Okruhlik Karen Williams Foyt, the Entertainment Chairperson Lauren Haase John Roberts at Lodge 88, helped with ticket sales. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

February 12 – 16, 2016

February 12 – 16, 2016 danceFilms.org | Filmlinc.org ta b l e o F CONTENTS DA N C E O N CAMERA F E S T I VA L Inaugurated in 1971, and co-presented with Dance Films Association and the Film Society of Lincoln Center since 1996 (now celebrating the 20th anniversary of this esteemed partnership), the annual festival is the most anticipated and widely attended dance film event in New York City. Each year artists, filmmakers and hundreds of film lovers come together to experience the latest in groundbreaking, thought-provoking, and mesmerizing cinema. This year’s festival celebrates everything from ballet and contemporary dance to the high-flying world of trapeze. ta b l e o F CONTENTS about dance Films association 4 Welcome 6 about dance on camera Festival 8 dance in Focus aWards 11 g a l l e ry e x h i b i t 13 Free events 14 special events 16 opening and closing programs 18 main slate 20 Full schedule 26 s h o r t s p r o g r a m s 32 cover: Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers in Kinetic Molpai, ca. 1935 courtesy of Jacob’s Pillow Dance festival archives this Page: The Dance Goodbye ron steinman back cover: Feelings are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer courtesy estate of warner JePson ABOUT DANCE dance Films association dance Films association and dance on camera board oF directors Festival staFF Greg Vander Veer Nancy Allison Donna Rubin Interim Executive Director President Virginia Brooks Liz Wolff Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Paul Galando Brian Cummings Joanna Ney Co-Curator Dance on Camera Festival Vice President and Chair of Ron -

DJ Skills the Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3

The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 1 74 The Rise of The Hip-hop DJ DJs were Hip-hop’s original architects, and remain crucial to its contin- ued development. Hip-hop is more than a style of music; it’s a culture. As with any culture, there are various artistic expressions of Hip-hop, the four principal expressions being: • visual art (graffiti) • dance (breaking, rocking, locking, and popping, collectively known in the media as “break dancing”) • literature (rap lyrics and slam poetry) • music (DJing and turntablism) Unlike the European Renaissance or the Ming Dynasty, Hip-hop is a culture that is very much alive and still evolving. Some argue that Hip-hop is the most influential cultural movement in history, point- ing to the globalization of Hip-hop music, fashion, and other forms of expression. Style has always been at the forefront of Hip-hop. Improvisation is called free styling, whether in rap, turntablism, breaking, or graf- fiti writing. Since everyone is using the essentially same tools (spray paint for graffiti writers, microphones for rappers and beat boxers, their bodies for dancers, and two turntables with a mixer for DJs), it’s the artists’ personal styles that set them apart. It’s no coincidence that two of the most authentic movies about the genesis of the move- ment are titled Wild Style and Style Wars. There are also many styles of writing the word “Hip-hop.” The mainstream media most often oscillates between “hip-hop” and “hip hop.” The Hiphop Archive at Harvard writes “Hiphop” as one word, 2 DJ Skills The Rise of the Hip-Hop DJ 3 with a capital H, embracing KRS-ONE’s line of reasoning that “Hiphop Kool DJ Herc is a culture with its own foundation narrative, history, natives, and 7 In 1955 in Jamaica, a young woman from the parish of Saint Mary mission.” After a great deal of input from many people in the Hip-hop community, I’ve decided to capitalize the word but keep the hyphen, gave birth to a son who would become the father of Hip-hop. -

'What Ever Happened to Breakdancing?'

'What ever happened to breakdancing?' Transnational h-hoy/b-girl networks, underground video magazines and imagined affinities. Mary Fogarty Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary MA in Popular Culture Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © November 2006 For my sister, Pauline 111 Acknowledgements The Canada Graduate Scholarship (SSHRC) enabled me to focus full-time on my studies. I would also like to express my deepest gratitude to my committee members: Andy Bennett, Hans A. Skott-Myhre, Nick Baxter-Moore and Will Straw. These scholars have shaped my ideas about this project in crucial ways. I am indebted to Michael Zryd and Francois Lukawecki for their unwavering kindness, encouragement and wisdom over many years. Steve Russell patiently began to teach me basic rules ofgrammar. Barry Grant and Eric Liu provided comments about earlier chapter drafts. Simon Frith, Raquel Rivera, Anthony Kwame Harrison, Kwande Kefentse and John Hunting offered influential suggestions and encouragement in correspondence. Mike Ripmeester, Sarah Matheson, Jeannette Sloniowski, Scott Henderson, Jim Leach, Christie Milliken, David Butz and Dale Bradley also contributed helpful insights in either lectures or conversations. AJ Fashbaugh supplied the soul food and music that kept my body and mind nourished last year. If AJ brought the knowledge then Matt Masters brought the truth. (What a powerful triangle, indeed!) I was exceptionally fortunate to have such noteworthy fellow graduate students. Cole Lewis (my summer writing partner who kept me accountable), Zorianna Zurba, Jana Tomcko, Nylda Gallardo-Lopez, Seth Mulvey and Pauline Fogarty each lent an ear on numerous much needed occasions as I worked through my ideas out loud. -

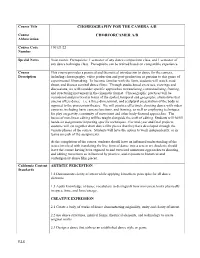

Choreography for the Camera AB

Course Title CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA A/B Course CHORFORCAMER A/B Abbreviation Course Code 190121/22 Number Special Notes Year course. Prerequisite: 1 semester of any dance composition class, and 1 semester of any dance technique class. Prerequisite can be waived based-on comparable experience. Course This course provides a practical and theoretical introduction to dance for the camera, Description including choreography, video production and post-production as pertains to this genre of experimental filmmaking. To become familiar with the form, students will watch, read about, and discuss seminal dance films. Through studio-based exercises, viewings and discussions, we will consider specific approaches to translating, contextualizing, framing, and structuring movement in the cinematic format. Choreographic practices will be considered and practiced in terms of the spatial, temporal and geographic alternatives that cinema offers dance – i.e. a three-dimensional, and sculptural presentation of the body as opposed to the proscenium theatre. We will practice effectively shooting dance with video cameras, including basic camera functions, and framing, as well as employing techniques for play on gravity, continuity of movement and other body-focused approaches. The basics of non-linear editing will be taught alongside the craft of editing. Students will fulfill hands-on assignments imparting specific techniques. For mid-year and final projects, students will cut together short dance film pieces that they have developed through the various phases of the course. Students will have the option to work independently, or in teams on each of the assignments. At the completion of the course, students should have an informed understanding of the issues involved with translating the live form of dance into a screen art. -

Sheet Music of Flashdance What a Feeling Irene Cara Clarinet Quintet You Need to Signup, Download Music Sheet Notes in Pdf Format Also Available for Offline Reading

Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Clarinet Quintet Sheet Music Download flashdance what a feeling irene cara clarinet quintet sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of flashdance what a feeling irene cara clarinet quintet sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 5589 times and last read at 2021-09-25 21:31:46. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of flashdance what a feeling irene cara clarinet quintet you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Bass Clarinet Ensemble: Clarinet Quintet, Woodwind Quintet Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara String Quintet Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara String Quintet sheet music has been read 6183 times. Flashdance what a feeling irene cara string quintet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 13:21:11. [ Read More ] Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Brass Quintet Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Brass Quintet sheet music has been read 4181 times. Flashdance what a feeling irene cara brass quintet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 14:07:20. [ Read More ] Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Sab Flashdance What A Feeling Irene Cara Sab sheet music has been read 2971 times. Flashdance what a feeling irene cara sab arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. -

Conducting an Animal Dance Party

Conducting an Animal Dance Party 1 Learning Objectives • Understand the research behind the Animal Dance Party • Understand the structure and outline of the activity for in-person and virtual parties • Review tips for running a successful recruitment party 2 Agenda • Why run a dance party? • Supplies, Set Up and Schedules • Running an In-Person Animal Dance Party • Running a Virtual Animal Dance Party • Tips & Tricks For Successful Recruitment Parties 3 Why run a dance party? • The goal of all You’re Invited parties are to spark interest in the girls so they will ask their parents/caregivers to attend. • Girls in Kindergarten – 3rd grade said they were likely to ask their parents to attend a dance party. • The dance party activity is adapted directly from our programming: Brownie Outdoor Art Creator badge. • Girls will earn their first Girl Scout patch for participating in the activity. 4 In-Person Party Supplies • At least 2-3 staff or volunteers • Council or event banner, tablecloth and decorations • Laptop or tablet to play music & register new families • Sign in sheets, pens/markers, name tags, index cards • Coloring books or games for younger siblings • Council Information Cards • What is Girl Scouts/Why Girl Scouts flyer • Calendar of upcoming council activities 5 In-Person Party Set Up Follow local + council guidelines on social distancing • Provide multiple sign-in sheets for parents to provide their contact information. 1. Registration • Display council branded signage and tablecloths; What is Girl Scouts/Why Girl Scouts flyer; council information cards; calendar of upcoming council events • Decorate for a party! Consider the theme but generally focus on bright and fun decorations 2. -

Recital Theme: So You Think You Can Dance

Recital Theme: So You Think You Can Dance GENRE LEVEL SONG ALBUM / ARTIST Ballet Baby Age 2-3 Hooray For Chasse Wake Up And Wiggle/Marie Barnett Ballet Baby Age 2-3 Wacky Wallaby Waltz Put On Your Dancing Shoes/Joanie Bartels Ballet I - II Age 8-12 9 Dancing Princesses Ballet I - II Teen/Adult Dance Of The Hours From the opera La Gioconda/Amilcare Ponchielli Ballet II Age 8-10 7 Dancing Princesses Ballet II - III Age 10-12 Copelia Waltz Coppelia/Delibes Ballet II - III Teen/Adult Danse Napolitiane Swan Lake/Tchaikovsky Ballet III - IV Teen/Adult Dance of The Reed Flutes Nutcracker Suite/Tchaikovsky Ballet IV Teen/Adult Paquita Allegro Paquita/La Bayadere Ballet IV - V Teen/Adult Paquita Coda Paquita/La Bayadere Pre-Ballet I - II Age 5-6 Sugar Plum Fairies Nutcracker Suite/Tchaikovsky Pre-Ballet I - II Age 6-8 Little Swans Swan Lake/Tchaikovsky Hip Hop I Age 6-8 Pon De Replay Music of the Sun/Rihanna Hip Hop I Age 9-12 Get Up Step Up Soundtrack/Ciara Hip Hop I - II Age 6-8 Move It Like This Move It Like This/Baja Men Hip Hop I - II Age 8-12 1,2 Step Goodies/Ciara and Missy Elliott Hip Hop I - II Age 10-12 Get Up "Step Up" Soundtrack/Ciara Hip Hop "The Longest Yard" Soundtrack/Jung Tru,King Jacob I - II Teen/Adult Errtime and Nelly Hip Hop I - II Teen/Adult Switch Lost and Found/Will Smith Hip Hop I - II Adult Yeah Confessions/Usher Hip Hop II Adult Let It Go Heaven Sent/Keyshia Cole feat. -

Chapter 6. the Voice of the Other America: African

Chapter 6 Th e Voice of the Other America African-American Music and Political Protest in the German Democratic Republic Michael Rauhut African-American music represents a synthesis of African and European tradi- tions, its origins reaching as far back as the early sixteenth century to the begin- ning of the systematic importation of “black” slaves to the European colonies of the American continent.1 Out of a plethora of forms and styles, three basic pil- lars of African-American music came to prominence during the wave of indus- trialization that took place at the start of the twentieth century: blues, jazz, and gospel. Th ese forms laid the foundation for nearly all important developments in popular music up to the present—whether R&B, soul and funk, house music, or hip-hop. Th anks to its continual innovation and evolution, African-American music has become a constitutive presence in the daily life of several generations. In East Germany, as throughout European countries on both sides of the Iron Curtain, manifold directions and derivatives of these forms took root. Th ey were carried through the airwaves and seeped into cultural niches until, fi nally, this music landed on the political agenda. Both fans and functionaries discovered an enormous social potential beneath the melodious surface, even if their aims were for the most part in opposition. For the government, the implicit rejection of the communist social model represented by African-American music was seen as a security issue and a threat to the stability of the system. Even though the state’s reactions became weaker over time, the offi cial interaction with African-American music retained a political connotation for the life of the regime. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice.