The Healing Fields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aki Ra Founded His Mine Mu- Seum, Which He Uses to Edu- Cate Visitors About the Risks of Unexploded Ordnance with a View to Avoiding Further Acci- Dents

Volume 19 No. 1 / May 2017 NewsleTTer PROJECT: CAMBODIA put the shell in his museum straightaway. Siem Reap, the second larg- est city in Cambodia, is where Aki Ra founded his mine mu- seum, which he uses to edu- cate visitors about the risks of unexploded ordnance with a view to avoiding further acci- dents. He also established and leads Cambodian Self Help Demining (CSHD), a small, highly professional mine clear- ance organisation. If that is not enough, he and his wife also founded an orphanage Photo: CSHD together, which around thirty Cambodia’s eastern provinces in particular contain a lot of mines and there children now call home, some are around 2,400 mines per kilometre on the Thai border. of whom have been injured by mines themselves. Aki Ra – a former child soldier There is a reason why mines and other weaponry are such who removes mines an important topic in Aki Ra’s life. Explosive remnants of war in Cambodia have killed or maimed 65,000 people in the last forty years – more than in almost any other country. World Without Mines is commit- ted to accelerating the clearance of mines in Cambodia. „I was showing a group of tourists around our mine muse- um recently when a man suddenly came running in,” Aki Ra tells us. „He had just seen children playing with an artillery shell only a hundred metres away.” Aki Ra left the visitors where they were and ran to find the children. They were actu- ally standing there with the shell in their hands. -

States' Commitment to Conventional Weapons Destruction F United

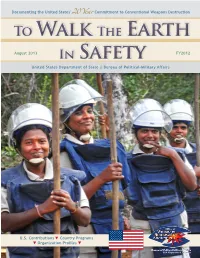

Documenting the United States’ Commitment to Conventional Weapons Destruction 20Year To Walk The Earth August 2013 In Safety FY2012 United States Department of State | Bureau of Political-Military Affairs U.S. Contributions Country Programs Organization Profiles 180 165 150 135 120 105 90 75 60 45 30 15 0 15 30 45 60 75 90 105 120 135 150 165 180 ON THE COVERS Table of Contents General Information 20 Years of U.S. Commitment to CWD ��������������������������������������������������������������������������4 Conventional Weapons Destruction Overview ����������������������������������������������������������������6 FY2012 Grantees �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 58 List of Common Acronyms . 60 FY2012 Funding Chart �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 61 U.S. Government Interagency Partners 75 Female deminers prepare for work in Sri Lanka. CDC �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 53 Sri Lanka is contaminated by landmines and ex- MANPADS Task Force . 56 plosive remnants of war from over three decades PM/WRA . 13 of armed conflict. From FY2002–FY2012 the U.S. has invested more than $35 million in convention- USAID ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 45 al weapons destruction programs in Sri Lanka. Photo courtesy of Sean Sutton/MAG. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE DTRA . -

Mine Action and Land Issues in Cambodia

Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining CheminEugène-Rigot 2C PO Box 1300, CH - 1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland T +41 (0)22 730 93 60 [email protected], www.gichd.org Doing no harm? Mine action and land issues in Cambodia Geneva, September 2014 The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), an international expert organisation legally based in Switzerland as a non-profit foundation, works for the elimination of mines, explosive remnants of war and other explosive hazards, such as unsafe munitions stockpiles. The GICHD provides advice and capacity development support, undertakes applied research, disseminates knowledge and best practices and develops standards. In cooperation with its partners, the GICHD's work enables national and local authorities in affected countries to effectively and efficiently plan, coordinate, implement, monitor and evaluate safe mine action programmes, as well as to implement the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, the Convention on Cluster Munitions and other relevant instruments of international law. The GICHD follows the humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence. Special thanks to Natalie Bugalski of Inclusive Development International for her contribution to this report. © Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the GICHD concerning the legal status of any country, territory or armed -

On Civilian Harm

On Civilian Harm Examining the complex negative effects of violent conflict on the lives of civilians None of us is in a position to eliminate war, but it is our obligation to denounce it and expose it in all its hideousness. War leaves no victors, only victims. ELIE WIESEL (NOBEL PRIZE LECTURE, 1986) On Civilian Harm Examining the complex negative effects of violent conflict on the lives of civilians Editors: Erin Bijl, Welmoet Wels & Wilbert van der Zeijden On civilian harm ON CIVILIAN HARM Examining the complex negative effects of violent conflict on the lives of civilians Editors: Erin Bijl, Welmoet Wels & Wilbert van der Zeijden Copy right: Copyright © by PAX 2021 Organisation: PAX, Protection of Civilians team Publication date: June 2021 Design/Lay-out: Het IJzeren Gordijn Printing company: Drukkerij Stetyco ISBN: 978-94-92487-57-5 Credits and permission for the use of particular images and illustrations are listed on the relevant pages and are considered a continuation of the copyright page. Please reach out to [email protected] in case of concerns or comments. An online version of this book and its individual chapters can be downloaded for free at https://protectionofcivilians.org. For questions about dissemination, presentations, content or other matters related to the book, reach out to [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, stored in a database and / or published in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, expect in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews and certain other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transnational Escape: Migrations of the Khmer and Cham Peoples of Cambodia (1832-2020) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6fv3712c Author Darnell, Ashley Faye Publication Date 2020 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Transnational Escape: Migrations of the Khmer and Cham Peoples of Cambodia (1832-2020) A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Southeast Asian Studies by Ashley Faye Darnell December 2020 Thesis Committee: Dr. Muhamad Ali, Chairperson Dr. David Biggs Dr. Matthew King Copyright by Ashley Faye Darnell 2020 The Thesis of Ashley Faye Darnell is approved: _________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the people of the Kingdom of Cambodia, and one person from South Korea, because without their helpful suggestions, guidance, brainstorming, oral history interviews, and input, this master's thesis would not have been possible. I am most indebted to the Khmer people of the Kingdom of Cambodia, particularly my three oral history interviewees, Wath Sawoeng, Thorn Bunthen, and Kheng -

'Finishing the Job' an Independent Review of Cambodia's Mine Action Sector

‘Finishing the Job’ An Independent Review of Cambodia’s Mine Action Sector Final report, 30 April 2016 A project funded by: 1 In a world where security and development are still hindered by explosive hazards, the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) works to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards. To achieve this, the GICHD supports national authorities, international organisations and civil society in their efforts to improve the relevance and performance of mine action. Core activities include furthering knowledge, promoting norms and standards, and developing in-country and international capacity. This support covers all aspects of mine action: strategic, managerial, operational and institutional. The GICHD works for mine action that is not an end in itself but contributes to the broader objective of human security – freedom from fear and freedom from want. This effort is facilitated by the GICHD’s location within the Maison de la paix in Geneva. This report was written by Annie Nut and Pascal Simon, independent consultants. © Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the GICHD concerning the legal status of any country, territory or armed groups, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. For further information, please contact: Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining Maison de la paix, Tower 3 Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2C, PO Box 1300 CH – 1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland [email protected] 2 Acknowledgements The review team would like to thank all organizations and individuals who participated in the mine action sector review mission in Cambodia, including HE Prum Sophakmonkol, Secretary General of the Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA) as well as his staff. -

2016 Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Prepared by Hargobind Khalsa with Oversight from William W. Morse APRIL, 2017 LANDMINE RELIEF FUND 16217 Kittridge Street Van Nuys, CA 91406 LANDMINE RELIEF FUND One mine - One life Contents Dietos Note .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Landmine Relief Fund Mission ...................................................................................................................... 2 Year Overview ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Financial Reports 2016 2015 Dietos Note o Fiaial Repots Graphs Cambodian Self-Help Demining Work .......................................................................................................... 7 Overview Total Land Area Cleared & Beneficiaries Total Mines, UXOs, and Arms Destroyed Map of Cleared Minefields in 2016 Rural School Villages Program Work ........................................................................................................... 11 Overview Details of Schools Added Goals for the Future .................................................................................................................................... 13 LANDMINE RELIEF FUND One mine - One life Director’s Note The Landmine Relief Fund (LMRF) was started a decade ago to support the work of an-ex-child soldier who was clearing landmines with a stick and caring for kids wounded -

Former Child Soldier Undoes Past, One Landmine at a Time - CNN.Com by Miranda Leitsinger , CNN November 10, 2009 -- Updated 0943 GMT (1743 HKT) CNN.Com

http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/asiapcf/10/28/cambodia.landmines/index.html?iref=mpstoryview Former child soldier undoes past, one landmine at a time - CNN.com By Miranda Leitsinger , CNN November 10, 2009 -- Updated 0943 GMT (1743 HKT) CNN.com Hong Kong, China (CNN) -- Aki Ra was forced to be a child soldier in the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia in the early 1980s, taught to shoot a gun and plant deadly landmines. He was later seized by the Cambodian army and the Vietnamese, who were fighting together against the ultra-Maoist Khmer Rouge, and he again planted explosives in the ground as war raged in the Southeast Asian nation. Years later, when the United Nations came in to help restore peace to Cambodia, Aki Ra decided he needed to undo the damage he and others had done, so he began demining on his own after spending a year training with U.N. deminers. "I have the idea from the U.N. to help make peace in Cambodia in 1992-1993, stop fighting, stop lay landmine," he said on a recent visit to Hong Kong, where he talked with students about his life and work. "I try to change from bad -- I want to be a good thing -- so I clear landmine to help make my country safe." Fact Box Landmines, unexploded ordnance in Cambodia -- At least 40,000 people living with injuries -- 65 people killed in 2007; 61 in 2006 -- Greatest concentration of mines is along parts of western and northern border with Thailand -- 90 percent of mine accidents and casualties in 2007 happen in five Cambodian provinces located on the Thai border Source: International Campaign to Ban Landmines Aki Ra, who believes he is about 40 years old, embarked upon a course that would change his life. -

Migrations of the Khmer and Cham Peoples of Cambodia (1832-2020) a Thes

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Transnational Escape: Migrations of the Khmer and Cham Peoples of Cambodia (1832-2020) A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Southeast Asian Studies by Ashley Faye Darnell December 2020 Thesis Committee: Dr. Muhamad Ali, Chairperson Dr. David Biggs Dr. Matthew King Copyright by Ashley Faye Darnell 2020 The Thesis of Ashley Faye Darnell is approved: _________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the people of the Kingdom of Cambodia, and one person from South Korea, because without their helpful suggestions, guidance, brainstorming, oral history interviews, and input, this master's thesis would not have been possible. I am most indebted to the Khmer people of the Kingdom of Cambodia, particularly my three oral history interviewees, Wath Sawoeng, Thorn Bunthen, and Kheng Bunny, of Siem Reap Province and Kandal Province, who shared their stories of migration within and away from their original hometowns. Their rich life experiences, which cover migration through Theravāda Buddhism; high school and higher education; teaching the Khmer language, culture, and history; tourism; overcoming medical illness and landmine explosions; travel within Cambodia and Thailand; and becoming respected people in their -

Finishing the Job: an Independent Review of the Mine Action Sector in Cambodia

‘Finishing the Job’ AN INDEPENDENT REVIEW OF THE MINE ACTION SECTOR IN CAMBODIA Final report, 30 April 2016 A project funded by: 1 In a world where security and development are still hindered by explosive hazards, the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) works to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards. To achieve this, the GICHD supports national authorities, international organisations and civil society in their efforts to improve the relevance and performance of mine action. Core activities include furthering knowledge, promoting norms and standards, and developing in-country and international capacity. This support covers all aspects of mine action: strategic, managerial, operational and institutional. The GICHD works for mine action that is not an end in itself but contributes to the broader objective of human security – freedom from fear and freedom from want. This effort is facilitated by the GICHD’s location within the Maison de la paix in Geneva. This report was written by Annie Nut and Pascal Simon, independent consultants. © Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the GICHD concerning the legal status of any country, territory or armed groups, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. For further information, please contact: Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining Maison de la paix, Tower 3 Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2C, PO Box 1300 CH – 1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland [email protected] 2 Acknowledgements The review team would like to thank all organizations and individuals who participated in the mine action sector review mission in Cambodia, including HE Prum Sophakmonkol, Secretary General of the Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA) as well as his staff. -

Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam

Your Guide to Responsible Tourism in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam Authors : Guy Marris Nick Ray Bernie Rosenbloom Editor : Ken Scott Your Guide to Responsible Tourism in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam ISBN : 321658741258 21 58 [ The Mekong River About the autors Laos author, Guy Marris, from New Zealand, arrived in Laos in 1997 with New Zealand Volunteer Service Abroad to work in Xe Piane National Protected Area. He has spent the last 10 years in Southeast Asia working in various protected areas throughout Laos and Cambodia as an advisor in conservation management and ecotourism development. More recently he has assisted both the Nam Ha National Protected Area in Laos and Virachey National Park in Cambodia with the development of community-based ecotourism programmes. Prior to that Guy worked as an officer with the New Zealand Wildlife Service and then as a director-cameraman on natural history documentaries. Guy is presently in Mozambique assisting in the management of Niassa National Reserve with Fauna and Flora International. He can be contacted at: [email protected]. After university, Nick Ray, a Londoner, combined writing and tour leading in countries as diverse as Vietnam and Morocco. He hooked up with Lonely Planet in 1998 and has worked on more than 20 titles over the following years. Cambodia is his backyard and he has worked on several editions of the Cambodia guide, as well as Southeast Asia on a shoestring and Cycling Vietnam, Laos & Cambodia. Nick also writes articles for leading magazines and newspapers, including The Sunday Times and Wanderlust. He is often a location scout and manager of film and TV projects. -

Mine Action and Land Issues in Cambodia

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Center for International Stabilization and Global CWD Repository Recovery 9-2014 Doing No Harm? Mine Action and Land Issues in Cambodia Geneva International Center for Humanitarian Demining Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-globalcwd Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Public Policy Commons, and the Social Policy Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Global CWD Repository by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining CheminEugène-Rigot 2C PO Box 1300, CH - 1211 Geneva 1, Switzerland T +41 (0)22 730 93 60 [email protected], www.gichd.org Doing no harm? Mine action and land issues in Cambodia Geneva, September 2014 The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD), an international expert organisation legally based in Switzerland as a non-profit foundation, works for the elimination of mines, explosive remnants of war and other explosive hazards, such as unsafe munitions stockpiles. The GICHD provides advice and capacity development support, undertakes applied research, disseminates knowledge and best practices and develops standards. In cooperation with its partners, the GICHD's work enables national and local authorities in affected countries to effectively and efficiently plan, coordinate, implement, monitor and evaluate safe mine action programmes, as well as to implement the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, the Convention on Cluster Munitions and other relevant instruments of international law.