Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Volume 66, Issue Number 41

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JPC.CCP Bureau Du Prdsident

Onchoccrciasis Control Programmc in the Volta Rivcr Basin arca Programme de Lutte contre I'Onchocercose dans la R6gion du Bassin de la Volta JOIN'T PROCRAMME COMMITTEE COMITE CONJOINT DU PROCRAMME Officc of the Chuirrrran JPC.CCP Bureau du Prdsident JOINT PROGRAII"IE COMMITTEE JPC3.6 Third session ORIGINAL: ENGLISH L Bamako 7-10 December 1982 October 1982 Provisional Agenda item 8 The document entitled t'Proposals for a Western Extension of the Prograncne in Mali, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ssnegal and Sierra Leone" was reviewed by the Corrrittee of Sponsoring Agencies (CSA) and is now transmitted for the consideration of the Joint Prograurne Conrnittee (JPC) at its third sessior:. The CSA recalls that the JPC, at its second session, following its review of the Feasibility Study of the Senegal River Basin area entitled "Senegambia Project : Onchocerciasis Control in Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, l,la1i, Senegal and Sierra Leone", had asked the Prograrrne to prepare a Plan of Operations for implementing activities in this area. It notes that the Expert Advisory Conrnittee (EAC) recormnended an alternative strategy, emphasizing the need to focus, in the first instance, on those areas where onchocerciasis was hyperendemic and on those rivers which were sources of reinvasion of the present OCP area (Document JPC3.3). The CSA endorses the need for onchocerciasis control in the Western extension area. However, following informal consultations, and bearing in mind the prevailing financial situation, the CSA reconrnends that activities be implemented in the area on a scale that can be managed by the Prograrmne and at a pace concomitant with the availability of funds, in order to obtain the basic data which have been identified as missing by the proposed plan of operations. -

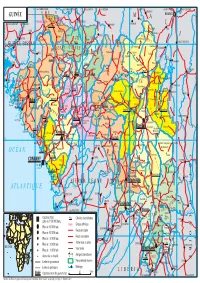

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (As of 17 Fev 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of N’Zérékoré Region (as of 17 Fev 2015) Banian SENEGAL Albadariah Mamouroudou MALI Djimissala Kobala Centre GUINEA-BISSAU Mognoumadou Morifindou GUINEA Karala Sangardo Linko Sessè Baladou Hérémakono Tininkoro Sirana De Beyla Manfran Silakoro Samala Soromaya Gbodou Sokowoulendou Kabadou Kankoro Tanantou Kerouane Koffra Bokodou Togobala Centre Gbangbadou Koroukorono Korobikoro Koro Benbèya Centre Gbenkoro SIERRA LEONE Kobikoro Firawa Sassèdou Korokoro Frawanidou Sokourala Vassiadou Waro Samarami Worocia Bakokoro Boukorodou Kamala Fassousso Kissidougou Banankoro Bablaro Bagnala Sananko Sorola Famorodou Fermessadou Pompo Damaro Koumandou Samana Deila Diassodou Mangbala Nerewa LIBERIA Beindou Kalidou Fassianso Vaboudou Binemoridou Faïdou Yaradou Bonin Melikonbo Banama Thièwa DjénédouKivia Feredou Yombiro M'Balia Gonkoroma Kemosso Tombadou Bardou Gberékan Sabouya Tèrèdou Bokoni Bolnin Boninfé Soumanso Beindou Bondodou Sasadou Mama Koussankoro Filadou Gnagbèdou Douala Sincy Faréma Sogboro Kobiramadou Nyadou Tinah Sibiribaro Ouyé Allamadou Fouala Regional Capital Bolodou Béindou Touradala Koïko Daway Fodou 1 Dandou Baïdou 1 Kayla Kama Sagnola Dabadou Blassana Kamian Laye Kondiadou Tignèko Kovila Komende Kassadou Solomana Bengoua Poveni Malla Angola Sokodou Niansoumandou Diani District Capital Kokouma Nongoa Koïko Frandou Sinko Ferela Bolodou Famoîla Mandou Moya Koya Nafadji Domba Koberno Mano Kama Baïzéa Vassala Madina Sèmèkoura Bagbé Yendemillimo Kambadou Mohomè Foomè Sondou Diaboîdou Malondou Dabadou Otol Beindou Koindou -

“If You Don't Find Anything, You Can't Eat” – Mining Livelihoods and Income, Gender Roles, and Food Choices In

Resources Policy 70 (2021) 101939 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Resources Policy journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/resourpol “If you don’t findanything, you can’t eat” – Mining livelihoods and income, gender roles, and food choices in northern Guinea Ronald Stokes-Walters a,d,*, Mohammed Lamine Fofana b, Joseph Lamil´e Songbono c, Alpha Oumar Barry c, Sadio Diallo c, Stella Nordhagen b,e, Laetitia X. Zhang a, Rolf D. Klemm a,b, Peter J. Winch a a Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health – 615 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA b Helen Keller International – One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, Floor 2, New York, NY, 10017, United States c Julius Nyerere University of Kankan, Kankan, Guinea d Action Against Hunger USA, One Whitehall St, Second Floor, New York NY, 10004, United States e Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), Rue de Vermont 37-39, 1202, Geneva, Switzerland ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) continues to grow as a viable economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa. Artisanal mining The health and environmental impacts of the industry, notably linked to the use of potentially toxic chemicals, Food choice has been well documented. What has not been explored to the same extent is how pressures associated with ASM Women’s workload affect food choices of individuals and families living in mining camps. This paper presents research conducted in Income instability 18 mining sites in northern Guinea exploring food choices and the various factors affecting food decision-making Guinea practices. Two of the most influentialfactors to emerge from this study are income variability and gender roles. -

IOM Guinea Ebola Response Situation Report, 8-31 March 2016

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION RAPPORT DE SITUATION From 8 to 31, March 2016 News Launching of the “soft ring containment” of Koropara sub-prefecture. © IOM Guinea 2016 On February 29 and March 17, three On March 9, 2016, IOM organized a From March 9 to 11, 2016, a joint IOM-RTI- people died in the sub-prefecture of ceremony during which, it officially handed- DPS mission went to different sub- Koropara following an unknown disease over the health post of Kamakouloun to sub- prefectures of Boffa for a maiden contact characterized by fever, deep emaciation, prefectural authorities of Kamsar, prefecture with local authorities. The aim was to explain diarrhea including vomiting of blood. A few of Boke. The health facility was rehabilitated the criteria used in the selection of CHA days later, two other people developed the and fully equipped by the organization. (Community Health Assistants), validating the same symptoms. The tests, carried out on list of CHA provided by the DPS in their March 17, were positive to the Ebola Virus localities and selecting 30 participants for the Disease, indicating the resurgence of the participatory mapping exercise (10 wise men, disease in Guinea, nearly three months after 10 youths and 10 women). it was officially declared over by WHO. Situation of the Ebola virus disease after its resurgence in Guinea In the sub-prefecture of Koropara, located at 97km from the city of NZerekore, an approximately 50-year-old farmer along with his two wives died between February 29 and March 17, 2016 following an unknown disease characterized by fever, deep emaciation, diarrhea and vomiting of blood. -

Guinea Ebola Response International Organization for Migration

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION RAPPORT DE SITUATION From 8 to 31, March 2016 News Launching of the “soft ring containment” of Koropara sub-prefecture. © IOM Guinea 2016 On February 29 and March 17, three On March 9, 2016, IOM organized a From March 9 to 11, 2016, a joint IOM-RTI- people died in the sub-prefecture of ceremony during which, it officially handed- DPS mission went to different sub- Koropara following an unknown disease over the health post of Kamakouloun to sub- prefectures of Boffa for a maiden contact characterized by fever, deep emaciation, prefectural authorities of Kamsar, prefecture with local authorities. The aim was to explain diarrhea including vomiting of blood. A few of Boke. The health facility was rehabilitated the criteria used in the selection of CHA days later, two other people developed the and fully equipped by the organization. (Community Health Assistants), validating the same symptoms. The tests, carried out on list of CHA provided by the DPS in their March 17, were positive to the Ebola Virus localities and selecting 30 participants for the Disease, indicating the resurgence of the participatory mapping exercise (10 wise men, disease in Guinea, nearly three months after 10 youths and 10 women). it was officially declared over by WHO. Situation of the Ebola virus disease after its resurgence in Guinea In the sub-prefecture of Koropara, located at 97km from the city of NZerekore, an approximately 50-year-old farmer along with his two wives died between February 29 and March 17, 2016 following an unknown disease characterized by fever, deep emaciation, diarrhea and vomiting of blood. -

Plan De Gestion Environnementale Et Sociale (Pges)

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE ***************** TRAVAIL - JUSTICE – SOLIDARITE DIRECTION NATIONALE DU GENIE RURAL ***************** SECRETARIAT EXECUTIF DE L’ABN Public Disclosure Authorized PROJET DE DEVELOPPEMENT DES RESSOURCES EN EAU ET DE GESTION DURABLE DES ECOSYSTEMES DANS LE BASSIN DU NIGER (PDREGDE) ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL, EVALUATION SOCIALE ET EVENTUELS PLANS D’ACTION DE REINSTALLATION DANS LE CADRE DE L’APPUI AUX TRAVAUX D’AMENAGEMENTS HYDRO AGRICOLES, A LA RESTAURATION ET LE DEVELOPPEMENT DES ACTIVITES AGROFORESTERIES ET DE PROTECTION DES VERSANTS DANS LA REGION DE FARANAH, REPUBLIQUE DE LA GUINEE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized FINANCEMENT IDA ETUDE D’IMPACT ENVIRONNEMENTAL ET SOCIAL VERSION PROVISOIRE CORRIGEE Public Disclosure Authorized Novembre 2013 SOCIETE D’ETUDES POLYTECHNIQUES Société à responsabilité limitée au capital de 1.500.000 F CFA BP: 3069 Bamako – N° Fiscal: 086 100086 V - Tél. : (+223) 20 20 69 29) SOMMAIRE ABREVIATIONS ET ACRONYMES.......................................................................................................... 5 LISTE DES TABLEAUX ET FIGURES ...................................................................................................... 6 RESUME ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... -

Scientific Coordinator's Report

P L E C N E W S A N D V I E W S No. 14 NOVEMBER 1999 PRINCIPAL SCIENTIFIC COORDINATOR’S REPORT 1 Highlights of the period April–November 1999 The new trend: helping to restore diversity 2 Demonstrating the value of agrodiversity in Ghana 3 New approaches, new methods, new mind-sets 3 Advances in survey methodology 4 Methodological papers in this issue 4 ‘Vive WAPLEC: Vive le PLEC’: Guinée September 1999 5 The workshop at Pita A visit to Moussaya, upper Niger 5 General remarks 6 MAY 1999 UNU/PLEC-BAG MEETING: SUMMARY AND DATA FORMS 7 D.J. Zarin, with inputs from Guo Huijun, Lewis Enu-Kwesi and Liang Luohui ATTRIBUTES REQUIRED OF THE NEW EXPERT 8 Comments by Professor E. Laing PAPER FROM THE DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES ADVISORY TEAM (DAT) 11 DAT facilitating the exchange of experiences in demonstration activities Miguel Pinedo-Vásquez SOME PLEC DEFINITIONS, WITH CODES FOR DATA-BASE PURPOSES 17 from the Editors A DIARY OF MEETINGS ATTENDED BY PLEC MEMBERS, MARCH– 18 NOVEMBER 1999 PAPERS BY PROJECT MEMBERS Mapping of settlements in an evolving PLEC demonstration site in Northern Ghana: an 19 example in collaborative and participatory work The late A.S. Abdulai, E.A. Gyasi and S.K. Kufogbe with assistance of P.K. Adraki, F. Asante, M.A. Asumah, B.Z. Gandaa, B.D. Ofori and A.S. Sumani Agrodiversity highlights in East Africa 25 F. Kaihura, R. Kiome, M. Stocking, A. Tengberg and J. Tumuhairwe An enlargement of PLEC work in Mexico 33 edited from a proposal to PLEC by Carlos Arriaga-Jordán A DIRECTORY OF PLEC DEMONSTRATION SITES, with date of firm 38 establishment, names of cluster leaders and e-mail and fax addresses P L E C N E W S A N D V I E W S No. -

REPUBLIC of GUINEA Labor–Justice–Solidarity

REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Labor–Justice–Solidarity MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND LIVESTOCK NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF RICE GROWING APRIL 2009 Table of contents LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 5 SUMMARY 6 I. INTRODUCTION 8 II. REVIEWING THE RICE SECTOR 9 2.1. The policy position of rice 10 2.2 Preferences and demand estimates 10 2.3 Typology and number of rice farmers, processors and marketers 11 2.4. Gender dimensions 13 2.5. Comparative advantage of national rice production 14 III. CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES 14 3.1. The potential of local rice for rural poverty reduction and economic growth 14 3.2. The land system 15 3.3. Social issues 16 3.4. Trans-border and regional issues 16 3.5. Knowledge and lessons learnt from R&D in rice 16 VI. PRIORITY AREAS AND PERSPECTIVES 17 4.1. Ranking by order of priority in terms of potential contribution to national production 17 4.2. Identification and ranking specific environmental challenges and related opportunities by order of priority 18 4.3. Identification of policy challenges/opportunities 20 4.3.1. Policy challenges 20 4.3.1. Opportunities 21 V. VISION AND FRAMEWORK OF THE NATIONAL RICE STRATEGY 21 5.1. Objectives of rice production 21 5.5.1. Overall target: 21 5.5.2. Quantified objectives: 21 5.2.3. Strategy development phase 23 5.2.4. Key interventions 24 5.2.5 Scientists, technicians and agricultural advisory agents in 2008 and beyond 25 5.2.6. Governance of the Rice Growing Development Strategy 25 5.2.7. -

GUINÉE Gam L BAMAKO PARC NAT

14° vers TAMBACOUNDA vers TAMBACOUNDA 12° vers SARAYA vers KÉNÉBIA 10° vers KITA vers KITA 8° vers KOULIKORO vers SÉGOU S É N É G A L F SIRAKORO bie a GUINÉE Gam l BAMAKO PARC NAT. é M m A DU KONIAGUI é GALÉ FOULAKOUNDA BADIAR KÉDOUGOU g L n i B vers ZIGUINCHOR vers KOLDA F f SAGABARI a Youkounkoun ARABA a k Koundara o B y ba ï G Niagassola SIBI ê Sarébo do a G GABU Guingan m o T i b B Balandou I o i al K m T e F LÉ é R iba ouba A A M ok l i Kifaya Tamgué D A o vers BISSAO o L ro F Á K n 1538 m I BA AT Foulamôri é Balaki I Sou baraya N K A É OUÉLÉSSÉBOUGOU 12° GUINÉE-BISSAO Mali L Boukaria 12° B S m a O a Naboun Kouré alé n l y N E - G U I N É o o KANGABA k Y E N E N k a é XIME O a r M m Madina l Ya béring F a ÉL K andanda Maléa B u B I m n Koumbia Sala bandé Doko o Kounsitél É i a e Siguirini Barrage B bi g è è R al m in Diatif r E de Sélingué vers BISSAO ub Gaoual a f Rio Cor G a IG KANGARÉ BUBA oumb B Banora N é K a Koubia Nafadji n Kintinian é i i Dabalaré F m Malanta ô F o K llé ifa BOUGOUNI Wéndou Mbôrou T Ganiakali Siguiri n Fouta Labé T H Dialakoro o Lélouma ougué A g Tin vers SIKASSO o 1245 U kisso K Hamdallaï Kâkoni F L T E Kiniébakoura K O U A Dinguiraye - G Balandougouba CATIÓ LÉ o U I SANSA g Sélouma N É E o ê Dabiss H rico a Kalinko Koundianakoro n Missira Kankalabé Sangarédi m F YANFOLILA i Chutes arakoba Niandankoro r o e k de Kinkon ka s n Sansalé L A Santou a Pita s i ou i m Sansando c U K B k Ko ola Koura Niantanina a u F O Tén n ié M Niani BADOGO L C ing ilin m é i n GARA O T ta Konsota i T a O io Dobali Djalon B m -

Impact of the Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak on Market Chains And

FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Dakar, 2016 The conclusions given in this information product are considered appropriate at the time of its preparation. They may be mod- ified in the light of further knowledge gained at subsequent stages of the project. In particular, the recommendations included in this information product were valid at the time they were written, during the FAO workshop on the market chains and trade of agricultural products in the context of the Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa, organized in December 2014 in Dakar, Senegal. The views expressed in this information product are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not men- tioned. ISBN 978-92-5-109223-1 © FAO, 2016 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise in- dicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

1 Republique De Guinee

Évaluation Finale du Projet « Renforcement de la Gestion Décentralisée de l’environnement UNDP-GUINEE 2018 pour répondre aux objectifs des Conventions de Rio en Guinée – RGDE » REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE ____________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ « Renforcement de la Gestion Décentralisée de l’Environnement pour répondre aux objectifs des Conventions de Rio en Guinée (RGDE-GIN- PIMS-4963 ; ID : 00093877) » ___________________ Rapport d’Évaluation Finale Soumis au PNUD-Guinée Maison Commune, Commune de Matam, Coléah Corniche Sud, Rue MA 002 Conakry, Guinée Par Dr Syaka SADIO, Consultant International, Chef d’équipe Et Alphonse Ngom, Consultant national Août 2018 1 Évaluation Finale du Projet « Renforcement de la Gestion Décentralisée de l’environnement UNDP-GUINEE 2018 pour répondre aux objectifs des Conventions de Rio en Guinée – RGDE » REMERCIEMENTS Les consultants tiennent à exprimer leurs sincères remerciements aux autorités du gouvernement de la Guinée et particulièrement le Ministère de l’Environnement, des Eaux et Forêts (MEEF) et le Programme pour l’environnement et le Développement Durable (PEDD) pour les dispositions prises pour faciliter cette mission et l’atteinte des résultats attendus. Nous remercions tout particulièrement le Bureau du PNUD-Guinée, le Directeur pays et le Directeur Adjoint pays, qui n’ont ménagé aucun effort pour donner des orientations claires à la mission. Aussi, que l’ensemble du personnel, trouve ici l’expression de nos meilleurs sentiments, pour la confiance portée en nous pour conduire l’évaluation terminale du projet, et plus particulièrement Mr. Mamadou Ciré Camara, Team Leader de l’Unité Environnement et Énergie et son équipe, notamment Mamadou kalidou Diallo, chargé du suivi à l’Unité Environnement et Énergie/PNUD, Mr Mamadou Diallo du Procurement -PNUD. -

Climate Change Analysis for Guinea Conakry with Homogenized Daily Dataset

CLIMATE CHANGE ANALYSIS FOR GUINEA CONAKRY WITH HOMOGENIZED DAILY DATASET. Abdoul Aziz Barry Dipòsit Legal: T 262-2015 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral.