The Grand Narrative of the Mukhomor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Occurrence of Psilocybin/Psilocin in Pluteus Salicinus (Pluteaceae)

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Biology Faculty Publications Biology 7-1981 Occurrence of psilocybin/psilocin in Pluteus salicinus (Pluteaceae) Stephen G. Saupe College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/biology_pubs Part of the Biology Commons, Botany Commons, and the Fungi Commons Recommended Citation Saupe SG. 1981. Occurrence of psilocybin/psilocin in Pluteus salicinus (Pluteaceae). Mycologia 73(4): 781-784. Copyright © 1981 Mycological Society of America. OCCURRENCE OF PSILOCYBIN/ PSILOCIN IN PLUTEUS SALICINUS (PLUTEACEAE) STEPHEN G. SAUPE Department of Botany, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801 The development of blue color in a basidiocarp after bruising is a reliable, although not infallible, field character for detecting the pres ence of the N-methylated tryptamines, psilocybin and psilocin (1, 2, 8). This color results from the stepwise oxidation of psilocybin to psi locin to a blue pigment (3). Pluteus salicinus (Pers. ex Fr.) Kummer (Pluteaceae) has a grey pileus with erect to depressed, blackish, spinu lose squamules in the center. It is distinguished from other species in section Pluteus by its bluish to olive-green stipe, the color intensify ing with age and bruising (10, 11 ). This study was initiated to deter mine if the bluing phenomenon exhibited by this fungus is due to the presence of psilocybin/psilocin. Pluteus salicinus (sgs-230, ILL) was collected on decaying wood in Brownfield Woods, Urbana, Illinois, a mixed mesophytic upland forest. Carpophores were solitary and uncommon. Although Singer (10) reponed that this fungus is common in some areas of North America and Europe, it is rare in Michigan (5). -

Bur¯Aq Depicted As Amanita Muscaria in a 15Th Century Timurid-Illuminated Manuscript?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 133–141 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.023 First published online September 24, 2019 Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in a 15th century Timurid-illuminated manuscript? ALAN PIPER* Independent Scholar, Newham, London, UK (Received: May 8, 2019; accepted: August 2, 2019) A series of illustrations in a 15th century Timurid manuscript record the mi’raj, the ascent through the seven heavens by Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam. Several of the illustrations depict Bur¯aq, the fabulous creature by means of which Mohammed achieves his ascent, with distinctive features of the Amanita muscaria mushroom. A. muscaria or “fly agaric” is a psychoactive mushroom used by Siberian shamans to enter the spirit world for the purposes of conversing with spirits or diagnosing and curing disease. Using an interdisciplinary approach, the author explores the routes by which Bur¯aq could have come to be depicted in this manuscript with the characteristics of a psychoactive fungus, when any suggestion that the Prophet might have had recourse to a drug to accomplish his spirit journey would be anathema to orthodox Islam. There is no suggestion that Mohammad’s night journey (isra) or ascent (mi’raj) was accomplished under the influence of a psychoactive mushroom or plant. Keywords: Mi’raj, Timurid, Central Asia, shamanism, Siberia, Amanita muscaria CULTURAL CONTEXT Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in the mi’raj manscript The mi’raj manuscript In the Muslim tradition, the mi’raj was preceded by the isra or “Night Journey” during which Mohammed traveled An illustrated manuscript depicting, in a series of miniatures, overnight from Mecca to Jerusalem by means of a fabulous thesuccessivestagesofthemi’raj, the miraculous ascent of beast called Bur¯aq. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

The Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: Diversity, Traditions, Use and Abuse with Special Reference to the Genus Psilocybe

11 The Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: Diversity, Traditions, Use and Abuse with Special Reference to the Genus Psilocybe Gastón Guzmán Instituto de Ecologia, Km 2.5 carretera antigua a Coatepec No. 351 Congregación El Haya, Apartado postal 63, Xalapa, Veracruz 91070, Mexico E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The traditions, uses and abuses, and studies of hallucinogenic mush- rooms, mostly species of Psilocybe, are reviewed and critically analyzed. Amanita muscaria seems to be the oldest hallucinogenic mushroom used by man, although the first hallucinogenic substance, LSD, was isolated from ergot, Claviceps purpurea. Amanita muscaria is still used in North Eastern Siberia and by some North American Indians. In the past, some Mexican Indians, as well as Guatemalan Indians possibly used A. muscaria. Psilocybe has more than 150 hallucinogenic species throughout the world, but they are used in traditional ways only in Mexico and New Guinea. Some evidence suggests that a primitive tribe in the Sahara used Psilocybe in religions ceremonies centuries before Christ. New ethnomycological observations in Mexico are also described. INTRODUCTION After hallucinogenic mushrooms were discovered in Mexico in 1956-1958 by Mr. and Mrs. Wasson and Heim (Heim, 1956; Heim and Wasson, 1958; Wasson, 1957; Wasson and Wasson, 1957) and Singer and Smith (1958), a lot of attention has been devoted to them, and many publications have 257 flooded the literature (e.g. Singer, 1958a, b, 1978; Gray, 1973; Schultes, 1976; Oss and Oeric, 1976; Pollock, 1977; Ott and Bigwood, 1978; Wasson, 1980; Ammirati et al., 1985; Stamets, 1996). However, not all the fungi reported really have hallucinogenic properties, because several of them were listed by erroneous interpretation of information given by the ethnic groups originally interviewed or by the bibliography. -

From Sacred Plants to Psychotherapy

From Sacred Plants to Psychotherapy: The History and Re-Emergence of Psychedelics in Medicine By Dr. Ben Sessa ‘The rejection of any source of evidence is always treason to that ultimate rationalism which urges forward science and philosophy alike’ - Alfred North Whitehead Introduction: What exactly is it that fascinates people about the psychedelic drugs? And how can we best define them? 1. Most psychiatrists will define psychedelics as those drugs that cause an acute confusional state. They bring about profound alterations in consciousness and may induce perceptual distortions as part of an organic psychosis. 2. Another definition for these substances may come from the cross-cultural dimension. In this context psychedelic drugs may be recognised as ceremonial religious tools, used by some non-Western cultures in order to communicate with the spiritual world. 3. For many lay people the psychedelic drugs are little more than illegal and dangerous drugs of abuse – addictive compounds, not to be distinguished from cocaine and heroin, which are only understood to be destructive - the cause of an individual, if not society’s, destruction. 4. But two final definitions for psychedelic drugs – and those that I would like the reader to have considered by the end of this article – is that the class of drugs defined as psychedelic, can be: a) Useful and safe medical treatments. Tools that as adjuncts to psychotherapy can be used to alleviate the symptoms and course of many mental illnesses, and 1 b) Vital research tools with which to better our understanding of the brain and the nature of consciousness. Classifying psychedelic drugs: 1,2 The drugs that are often described as the ‘classical’ psychedelics include LSD-25 (Lysergic Diethylamide), Mescaline (3,4,5- trimethoxyphenylathylamine), Psilocybin (4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and DMT (dimethyltryptamine). -

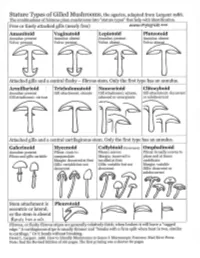

Agarics-Stature-Types.Pdf

Gilled Mushroom Genera of Chicago Region, by stature type and spore print color. Patrick Leacock – June 2016 Pale spores = white, buff, cream, pale green to Pinkish spores Brown spores = orange, Dark spores = dark olive, pale lilac, pale pink, yellow to pale = salmon, yellowish brown, rust purplish brown, orange pinkish brown brown, cinnamon, clay chocolate brown, Stature Type brown smoky, black Amanitoid Amanita [Agaricus] Vaginatoid Amanita Volvariella, [Agaricus, Coprinus+] Volvopluteus Lepiotoid Amanita, Lepiota+, Limacella Agaricus, Coprinus+ Pluteotoid [Amanita, Lepiota+] Limacella Pluteus, Bolbitius [Agaricus], Coprinus+ [Volvariella] Armillarioid [Amanita], Armillaria, Hygrophorus, Limacella, Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Coprinus+, Hypholoma, Neolentinus, Pleurotus, Tricholoma Cyclocybe, Gymnopilus Lacrymaria, Stropharia Hebeloma, Hemipholiota, Hemistropharia, Inocybe, Pholiota Tricholomatoid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Laccaria, Lactarius, Entoloma Cortinarius, Hebeloma, Lyophyllum, Megacollybia, Melanoleuca, Inocybe, Pholiota Russula, Tricholoma, Tricholomopsis Naucorioid Clitocybe, Hygrophorus, Hypsizygus, Laccaria, Entoloma Agrocybe, Cortinarius, Hypholoma Lactarius, Rhodocollybia, Rugosomyces, Hebeloma, Gymnopilus, Russula, Tricholoma Pholiota, Simocybe Clitocyboid Ampulloclitocybe, Armillaria, Cantharellus, Clitopilus Paxillus, [Pholiota], Clitocybe, Hygrophoropsis, Hygrophorus, Phylloporus, Tapinella Laccaria, Lactarius, Lactifluus, Lentinus, Leucopaxillus, Lyophyllum, Omphalotus, Panus, Russula Galerinoid Galerina, Pholiotina, Coprinus+, -

Toxicological and Pharmacological Profile of Amanita Muscaria (L.) Lam

Pharmacia 67(4): 317–323 DOI 10.3897/pharmacia.67.e56112 Review Article Toxicological and pharmacological profile of Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. – a new rising opportunity for biomedicine Maria Voynova1, Aleksandar Shkondrov2, Magdalena Kondeva-Burdina1, Ilina Krasteva2 1 Laboratory of Drug metabolism and drug toxicity, Department “Pharmacology, Pharmacotherapy and Toxicology”, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University of Sofia, Bulgaria 2 Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University of Sofia, Bulgaria Corresponding author: Magdalena Kondeva-Burdina ([email protected]) Received 2 July 2020 ♦ Accepted 19 August 2020 ♦ Published 26 November 2020 Citation: Voynova M, Shkondrov A, Kondeva-Burdina M, Krasteva I (2020) Toxicological and pharmacological profile of Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. – a new rising opportunity for biomedicine. Pharmacia 67(4): 317–323. https://doi.org/10.3897/pharmacia.67. e56112 Abstract Amanita muscaria, commonly known as fly agaric, is a basidiomycete. Its main psychoactive constituents are ibotenic acid and mus- cimol, both involved in ‘pantherina-muscaria’ poisoning syndrome. The rising pharmacological and toxicological interest based on lots of contradictive opinions concerning the use of Amanita muscaria extracts’ neuroprotective role against some neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, its potent role in the treatment of cerebral ischaemia and other socially significant health conditions gave the basis for this review. Facts about Amanita muscaria’s morphology, chemical content, toxicological and pharmacological characteristics and usage from ancient times to present-day’s opportunities in modern medicine are presented. Keywords Amanita muscaria, muscimol, ibotenic acid Introduction rica, the genus had an ancestral origin in the Siberian-Be- ringian region in the Tertiary period (Geml et al. -

Amanita Muscaria (Fly Agaric)

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2018; 48: 85–91 | doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2018.119 PAPER Amanita muscaria (fly agaric): from a shamanistic hallucinogen to the search for acetylcholine HistoryMR Lee1, E Dukan2, I Milne3 & Humanities The mushroom Amanita muscaria (fly agaric) is widely distributed Correspondence to: throughout continental Europe and the UK. Its common name suggests MR Lee Abstract that it had been used to kill flies, until superseded by arsenic. The bioactive 112 Polwarth Terrace compounds occurring in the mushroom remained a mystery for long Merchiston periods of time, but eventually four hallucinogens were isolated from the Edinburgh EH11 1NN fungus: muscarine, muscimol, muscazone and ibotenic acid. UK The shamans of Eastern Siberia used the mushroom as an inebriant and a hallucinogen. In 1912, Henry Dale suggested that muscarine (or a closely related substance) was the transmitter at the parasympathetic nerve endings, where it would produce lacrimation, salivation, sweating, bronchoconstriction and increased intestinal motility. He and Otto Loewi eventually isolated the transmitter and showed that it was not muscarine but acetylcholine. The receptor is now known variously as cholinergic or muscarinic. From this basic knowledge, drugs such as pilocarpine (cholinergic) and ipratropium (anticholinergic) have been shown to be of value in glaucoma and diseases of the lungs, respectively. Keywords acetylcholine, atropine, choline, Dale, hyoscine, ipratropium, Loewi, muscarine, pilocarpine, physostigmine Declaration of interests No conflicts of interest declared Introduction recorded by the Swedish-American ethnologist Waldemar Jochelson, who lived with the tribes in the early part of the Amanita muscaria is probably the most easily recognised 20th century. His version of the tale reads as follows: mushroom in the British Isles with its scarlet cap spotted 1 with conical white fl eecy scales. -

The Ectomycorrhizal Fungus Amanita Phalloides Was Introduced and Is

Molecular Ecology (2009) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04030.x TheBlackwell Publishing Ltd ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita phalloides was introduced and is expanding its range on the west coast of North America ANNE PRINGLE,* RACHEL I. ADAMS,† HUGH B. CROSS* and THOMAS D. BRUNS‡ *Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Biological Laboratories, 16 Divinity Avenue, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA, †Department of Biological Sciences, Gilbert Hall, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5020, USA, ‡Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, 111 Koshland Hall, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Abstract The deadly poisonous Amanita phalloides is common along the west coast of North America. Death cap mushrooms are especially abundant in habitats around the San Francisco Bay, California, but the species grows as far south as Los Angeles County and north to Vancouver Island, Canada. At different times, various authors have considered the species as either native or introduced, and the question of whether A. phalloides is an invasive species remains unanswered. We developed four novel loci and used these in combination with the EF1α and IGS loci to explore the phylogeography of the species. The data provide strong evidence for a European origin of North American populations. Genetic diversity is generally greater in European vs. North American populations, suggestive of a genetic bottleneck; polymorphic sites of at least two loci are only polymorphic within Europe although the number of individuals sampled from Europe was half the number sampled from North America. Endemic alleles are not a feature of North American populations, although alleles unique to different parts of Europe were common and were discovered in Scandinavian, mainland French, and Corsican individuals. -

Amanita Muscaria: Ecology, Chemistry, Myths

Entry Amanita muscaria: Ecology, Chemistry, Myths Quentin Carboué * and Michel Lopez URD Agro-Biotechnologies Industrielles (ABI), CEBB, AgroParisTech, 51110 Pomacle, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Definition: Amanita muscaria is the most emblematic mushroom in the popular representation. It is an ectomycorrhizal fungus endemic to the cold ecosystems of the northern hemisphere. The basidiocarp contains isoxazoles compounds that have specific actions on the central nervous system, including hallucinations. For this reason, it is considered an important entheogenic mushroom in different cultures whose remnants are still visible in some modern-day European traditions. In Siberian civilizations, it has been consumed for religious and recreational purposes for millennia, as it was the only inebriant in this region. Keywords: Amanita muscaria; ibotenic acid; muscimol; muscarine; ethnomycology 1. Introduction Thanks to its peculiar red cap with white spots, Amanita muscaria (L.) Lam. is the most iconic mushroom in modern-day popular culture. In many languages, its vernacular names are fly agaric and fly amanita. Indeed, steeped in a bowl of milk, it was used to Citation: Carboué, Q.; Lopez, M. catch flies in houses for centuries in Europe due to its ability to attract and intoxicate flies. Amanita muscaria: Ecology, Chemistry, Although considered poisonous when ingested fresh, this mushroom has been consumed Myths. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 905–914. as edible in many different places, such as Italy and Mexico [1]. Many traditional recipes https://doi.org/10.3390/ involving boiling the mushroom—the water containing most of the water-soluble toxic encyclopedia1030069 compounds is then discarded—are available. In Japan, the mushroom is dried, soaked in brine for 12 weeks, and rinsed in successive washings before being eaten [2]. -

Mycological Investigations on Teonanacatl the Mexican Hallucinogenic Mushroom

Mycological investigations on Teonanacatl, the mexican hallucinogenic mushroom by Rolf Singer Part I & II Mycologia, vol. 50, 1958 © Rolf Singer original report: https://mycotek.org/index.php?attachments/mycological-investigations-on-teonanacatl-the-mexian-hallucinogenic-mushroom-part-i-pdf.511 66/ Table of Contents: Part I. The history of Teonanacatl, field work and culture work 1. History 2. Field and culture work in 1957 Acknowledgments Literature cited Part II. A taxonomic monograph of psilocybe, section caerulescentes Psilocybe sect. Caerulescentes Sing., Sydowia 2: 37. 1948. Summary or the stirpes Stirps. Cubensis Stirps. Yungensis Stirps. Mexicana Stirps. Silvatica Stirps. Cyanescens Stirps. Caerulescens Stirps. Caerulipes Key to species of section Caerulescentes Stirps Cubensis Psilocybe cubensis (Earle) Sing Psilocybe subaeruginascens Höhnel Psilocybe aerugineomaculans (Höhnel) Stirps Yungensis Psilocybe yungensis Singer and Smith Stirps Mexicana Psilocybe mexicana Heim Stirps Silvatica Psilocybe silvatica (Peck) Psilocybe pelliculosa (Smith) Stirps Cyanescens Psilocybe aztecorum Heim Psilocybe cyanescens Wakefield Psilocybe collybioides Singer and Smith Description of Maire's sterile to semi-sterile material from Algeria Description of fertile material referred to Hypholoma cyanescens by Malençon Psilocybe strictipes Singer & Smith Psilocybe baeocystis Singer and Smith soma rights re-served 1 since 27.10.2016 at http://www.en.psilosophy.info/ mycological investigations on teonanacatl the mexican hallucinogenic mushroom www.en.psilosophy.info/zzvhmwgkbubhbzcmcdakcuak Stirps Caerulescens Psilocybe aggericola Singer & Smith Psilocybe candidipes Singer & Smith Psilocybe zapotecorum Heim Stirps Caerulipes Psilocybe Muliercula Singer & Smith Psilocybe caerulipes (Peck) Sacc. Literature cited soma rights re-served 2 since 27.10.2016 at http://www.en.psilosophy.info/ mycological investigations on teonanacatl the mexican hallucinogenic mushroom www.en.psilosophy.info/zzvhmwgkbubhbzcmcdakcuak Part I. -

The White Panther – Rare Exposure to Amanita Multisquamosa Causing Clinically Significant Toxicity

Clinical Toxicology ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ictx20 The White Panther – Rare exposure to Amanita multisquamosa causing clinically significant toxicity V. Vohra, I. V. Hull & K. T. Hodge To cite this article: V. Vohra, I. V. Hull & K. T. Hodge (2021): The White Panther – Rare exposure to Amanitamultisquamosa causing clinically significant toxicity, Clinical Toxicology, DOI: 10.1080/15563650.2021.1891242 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2021.1891242 Published online: 23 Feb 2021. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ictx20 CLINICAL TOXICOLOGY https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2021.1891242 LETTER TO THE EDITOR The White Panther – Rare exposure to Amanita multisquamosa causing clinically significant toxicity To the Editor, signs and labs remained unremarkable. Her mental status The mushroom genus Amanita includes over 200 North started improving 14 h post-exposure. She was discharged on American species. Some are edible, however some are toxic hospital day two. and potentially fatal if ingested [1]. Amanita multisquamosa Mushroom specimens were sent to mycologists at Cornell is known as the “white panther” or “small funnel-veil University for analysis, including examination of macroscopic Amanita” [2]. We present a rare case of toxicity from con- features like stature, odor, pale brown cap with a darker cen- firmed Amanita multisquamosa ingestion. ter and striate margin, pale prominent warts, and truncate A 30-year-old female, with no past medical history and no lamellulae (Figure 1).