Exact Distribution of Divergence Times from Fossil Ages and Topologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reptile Family Tree

Reptile Family Tree - Peters 2015 Distribution of Scales, Scutes, Hair and Feathers Fish scales 100 Ichthyostega Eldeceeon 1990.7.1 Pederpes 91 Eldeceeon holotype Gephyrostegus watsoni Eryops 67 Solenodonsaurus 87 Proterogyrinus 85 100 Chroniosaurus Eoherpeton 94 72 Chroniosaurus PIN3585/124 98 Seymouria Chroniosuchus Kotlassia 58 94 Westlothiana Casineria Utegenia 84 Brouffia 95 78 Amphibamus 71 93 77 Coelostegus Cacops Paleothyris Adelospondylus 91 78 82 99 Hylonomus 100 Brachydectes Protorothyris MCZ1532 Eocaecilia 95 91 Protorothyris CM 8617 77 95 Doleserpeton 98 Gerobatrachus Protorothyris MCZ 2149 Rana 86 52 Microbrachis 92 Elliotsmithia Pantylus 93 Apsisaurus 83 92 Anthracodromeus 84 85 Aerosaurus 95 85 Utaherpeton 82 Varanodon 95 Tuditanus 91 98 61 90 Eoserpeton Varanops Diplocaulus Varanosaurus FMNH PR 1760 88 100 Sauropleura Varanosaurus BSPHM 1901 XV20 78 Ptyonius 98 89 Archaeothyris Scincosaurus 77 84 Ophiacodon 95 Micraroter 79 98 Batropetes Rhynchonkos Cutleria 59 Nikkasaurus 95 54 Biarmosuchus Silvanerpeton 72 Titanophoneus Gephyrostegeus bohemicus 96 Procynosuchus 68 100 Megazostrodon Mammal 88 Homo sapiens 100 66 Stenocybus hair 91 94 IVPP V18117 69 Galechirus 69 97 62 Suminia Niaftasuchus 65 Microurania 98 Urumqia 91 Bruktererpeton 65 IVPP V 18120 85 Venjukovia 98 100 Thuringothyris MNG 7729 Thuringothyris MNG 10183 100 Eodicynodon Dicynodon 91 Cephalerpeton 54 Reiszorhinus Haptodus 62 Concordia KUVP 8702a 95 59 Ianthasaurus 87 87 Concordia KUVP 96/95 85 Edaphosaurus Romeria primus 87 Glaucosaurus Romeria texana Secodontosaurus -

HOVASAURUS BOULEI, an AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN from the UPPER PERMIAN of MADAGASCAR by P.J

99 Palaeont. afr., 24 (1981) HOVASAURUS BOULEI, AN AQUATIC EOSUCHIAN FROM THE UPPER PERMIAN OF MADAGASCAR by P.J. Currie Provincial Museum ofAlberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T5N OM6, Canada ABSTRACT HovasauTUs is the most specialized of four known genera of tangasaurid eosuchians, and is the most common vertebrate recovered from the Lower Sakamena Formation (Upper Per mian, Dzulfia n Standard Stage) of Madagascar. The tail is more than double the snout-vent length, and would have been used as a powerful swimming appendage. Ribs are pachyostotic in large animals. The pectoral girdle is low, but massively developed ventrally. The front limb would have been used for swimming and for direction control when swimming. Copious amounts of pebbles were swallowed for ballast. The hind limbs would have been efficient for terrestrial locomotion at maturity. The presence of long growth series for Ho vasaurus and the more terrestrial tan~saurid ThadeosauTUs presents a unique opportunity to study differences in growth strategies in two closely related Permian genera. At birth, the limbs were relatively much shorter in Ho vasaurus, but because of differences in growth rates, the limbs of Thadeosau rus are relatively shorter at maturity. It is suggested that immature specimens of Ho vasauTUs spent most of their time in the water, whereas adults spent more time on land for mating, lay ing eggs and/or range dispersal. Specilizations in the vertebrae and carpus indicate close re lationship between Youngina and the tangasaurids, but eliminate tangasaurids from consider ation as ancestors of other aquatic eosuchians, archosaurs or sauropterygians. CONTENTS Page ABREVIATIONS . ..... ... ......... .......... ... ......... ..... ... ..... .. .... 101 INTRODUCTION . -

2018 NMGS Spring Meeting: Abstract-748

FIRST DISCOVERY OF A TETRAPOD BODY FOSSIL IN THE LOWER PERMIAN YESO GROUP, CENTRAL NEW MEXICO Emily D. Thorpe1, Spencer G. Lucas2, David S. Berman3, Larry F. Rinehart2, Vincent Santucci4 and Amy C. Henrici3 1 POBox 147, Morrisonville, WI, 53571, [email protected] 2New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 1801 Mountain Road N. W., Albuquerque, NM, 87104 3Carnegie Museum of Natural History, 4400 Forbes Ave, Pittsburgh, PA, 15213 4National Parks Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Washington, DC, 20240, United States The lower Permian Yeso Group records arid coastal plain, shallow marine, and evaporitic deposition across much of central New Mexico. Generally considered to have few fossils, recent study of Yeso Group strata has discovered a diverse fossil record of marine micro-organisms (mostly algae and foraminiferans), terrestrial plants, and tetrapod footprints. We report here the first discovery of a tetrapod body fossil in the Yeso Group—a partial skeleton of a basal synapsid, varanopidae eupelycosaur. The fossil is the natural casts of bones in two pieces, part and counterpart, that were preserved in a sandstone bed of the lower part of the Arroyo de Alamillo Formation in the southern Manzano Mountains. The fossil-bearing sandstone is fine-grained, quartz rich, and pale reddish brown to grayish red unweathered, weathers to blackish red, and is in part encrusted by white caliche. The casts preserve part of the pelvis(?), 18 caudal vertebral centra, both femora and tibia-fibulae, and most of the pedes, largely in close articulation, of a single individual. The skeleton is of a relatively small (femur length = 62 mm, total length of the preserved cast from the pelvis to tip of the incomplete tail = 325 mm) and gracile eupelycosaur most similar to Varanops. -

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha)

Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) by Richard Kissel A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto © Copyright by Richard Kissel 2010 Morphology, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Diadectidae (Cotylosauria: Diadectomorpha) Richard Kissel Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto 2010 Abstract Based on dental, cranial, and postcranial anatomy, members of the Permo-Carboniferous clade Diadectidae are generally regarded as the earliest tetrapods capable of processing high-fiber plant material; presented here is a review of diadectid morphology, phylogeny, taxonomy, and paleozoogeography. Phylogenetic analyses support the monophyly of Diadectidae within Diadectomorpha, the sister-group to Amniota, with Limnoscelis as the sister-taxon to Tseajaia + Diadectidae. Analysis of diadectid interrelationships of all known taxa for which adequate specimens and information are known—the first of its kind conducted—positions Ambedus pusillus as the sister-taxon to all other forms, with Diadectes sanmiguelensis, Orobates pabsti, Desmatodon hesperis, Diadectes absitus, and (Diadectes sideropelicus + Diadectes tenuitectes + Diasparactus zenos) representing progressively more derived taxa in a series of nested clades. In light of these results, it is recommended herein that the species Diadectes sanmiguelensis be referred to the new genus -

Morphology and Evolutionary Significance of the Atlas−Axis Complex in Varanopid Synapsids

Morphology and evolutionary significance of the atlas−axis complex in varanopid synapsids NICOLÁS E. CAMPIONE and ROBERT R. REISZ Campione, N.E. and Reisz, R.R. 2011. Morphology and evolutionary significance of the atlas−axis complex in varanopid synapsids. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56 (4): 739–748. The atlas−axis complex has been described in few Palaeozoic taxa, with little effort being placed on examining variation of this structure within a small clade. Most varanopids, members of a clade of gracile synapsid predators, have well pre− served atlas−axes permitting detailed descriptions and examination of morphological variation. This study indicates that the size of the transverse processes on the axis and the shape of the axial neural spine vary among members of this clade. In particular, the small mycterosaurine varanopids possess small transverse processes that point posteroventrally, and the axial spine is dorsoventrally short, with a flattened dorsal margin in lateral view. The larger varanodontine varanopids have large transverse processes with a broad base, and a much taller axial spine with a rounded dorsal margin in lateral view. Based on outgroup comparisons, the morphology exhibited by the transverse processes is interpreted as derived in varanodontines, whereas the morphology of the axial spine is derived in mycterosaurines. The axial spine anatomy of Middle Permian South African varanopids is reviewed and our interpretation is consistent with the hypothesis that at least two varanopid taxa are present in South Africa, a region overwhelmingly dominated by therapsid synapsids and parareptiles. Key words: Synapsida, Varanopidae, Mycterosaurinae, Varanodontinae, atlas−axis complex, axial skeleton, Middle Permian, South Africa. -

A Small Lepidosauromorph Reptile from the Early Triassic of Poland

A SMALL LEPIDOSAUROMORPH REPTILE FROM THE EARLY TRIASSIC OF POLAND SUSAN E. EVANS and MAGDALENA BORSUK−BIAŁYNICKA Evans, S.E. and Borsuk−Białynicka, M. 2009. A small lepidosauromorph reptile from the Early Triassic of Poland. Palaeontologia Polonica 65, 179–202. The Early Triassic karst deposits of Czatkowice quarry near Kraków, southern Poland, has yielded a diversity of fish, amphibians and small reptiles. Two of these reptiles are lepido− sauromorphs, a group otherwise very poorly represented in the Triassic record. The smaller of them, Sophineta cracoviensis gen. et sp. n., is described here. In Sophineta the unspecial− ised vertebral column is associated with the fairly derived skull structure, including the tall facial process of the maxilla, reduced lacrimal, and pleurodonty, that all resemble those of early crown−group lepidosaurs rather then stem−taxa. Cladistic analysis places this new ge− nus as the sister group of Lepidosauria, displacing the relictual Middle Jurassic genus Marmoretta and bringing the origins of Lepidosauria closer to a realistic time frame. Key words: Reptilia, Lepidosauria, Triassic, phylogeny, Czatkowice, Poland. Susan E. Evans [[email protected]], Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, Uni− versity College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK. Magdalena Borsuk−Białynicka [[email protected]], Institut Paleobiologii PAN, Twarda 51/55, PL−00−818 Warszawa, Poland. Received 8 March 2006, accepted 9 January 2007 180 SUSAN E. EVANS and MAGDALENA BORSUK−BIAŁYNICKA INTRODUCTION Amongst living reptiles, lepidosaurs (snakes, lizards, amphisbaenians, and tuatara) form the largest and most successful group with more than 7 000 widely distributed species. The two main lepidosaurian clades are Rhynchocephalia (the living Sphenodon and its extinct relatives) and Squamata (lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians). -

Tiago Rodrigues Simões

Diapsid Phylogeny and the Origin and Early Evolution of Squamates by Tiago Rodrigues Simões A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in SYSTEMATICS AND EVOLUTION Department of Biological Sciences University of Alberta © Tiago Rodrigues Simões, 2018 ABSTRACT Squamate reptiles comprise over 10,000 living species and hundreds of fossil species of lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians, with their origins dating back at least as far back as the Middle Jurassic. Despite this enormous diversity and a long evolutionary history, numerous fundamental questions remain to be answered regarding the early evolution and origin of this major clade of tetrapods. Such long-standing issues include identifying the oldest fossil squamate, when exactly did squamates originate, and why morphological and molecular analyses of squamate evolution have strong disagreements on fundamental aspects of the squamate tree of life. Additionally, despite much debate, there is no existing consensus over the composition of the Lepidosauromorpha (the clade that includes squamates and their sister taxon, the Rhynchocephalia), making the squamate origin problem part of a broader and more complex reptile phylogeny issue. In this thesis, I provide a series of taxonomic, phylogenetic, biogeographic and morpho-functional contributions to shed light on these problems. I describe a new taxon that overwhelms previous hypothesis of iguanian biogeography and evolution in Gondwana (Gueragama sulamericana). I re-describe and assess the functional morphology of some of the oldest known articulated lizards in the world (Eichstaettisaurus schroederi and Ardeosaurus digitatellus), providing clues to the ancestry of geckoes, and the early evolution of their scansorial behaviour. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE AMY C. HENRICI Collection Manager Section of Vertebrate Paleontology Carnegie Museum of Natural History 4400 Forbes Avenue Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213-4080, USA Phone:(412)622-1915 Email: [email protected] BACKGROUND Birthdate: 24 September 1957. Birthplace: Pittsburgh. Citizenship: USA. EDUCATION B.A. 1979, Hiram College, Ohio (Biology) M.S. 1989, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Geology) CAREER Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) Laboratory Technician, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1979 Research Assistant, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1980 Curatorial Assistant, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1980-1984 Scientific Preparator, Section of Paleobotany, 1985-1986 Scientific Preparator, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1985-2002 Acting Collection Manager/Scientific Preparator, 2003-2004 Collection Manager, 2005-present PALEONTOLOGICAL FIELD EXPERIENCE Late Pennsylvanian through Early Permian of Colorado, New Mexico and Utah (fish, amphibians and reptiles) Early Permian of Germany, Bromacker quarry (amphibians and reptiles) Triassic of New Mexico, Coelophysis quarry (Coelophysis and other reptiles) Upper Jurassic of Colorado (mammals and herps) Tertiary of Montana, Nevada, and Wyoming (mammals and herps) Pleistocene of West Virginia (mammals and herps) Lake sediment cores and lake sediment surface samples, Wyoming (pollen and seeds) PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Associate Editor, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, 1998-2000. Research Associate in the Science Division, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, 2007-present. PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paleontological Society LECTURES and TUTORIALS (Invited and public) 1994. Middle Eocene frogs from central Wyoming: ontogeny and taphonomy. California State University, San Bernardino 1994. Mechanical preparation of vertebrate fossils. California State University, San Bernardino 1994. Mechanical preparation of vertebrate fossils. University of Chicago 2001. -

Physical and Environmental Drivers of Paleozoic Tetrapod Dispersal Across Pangaea

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07623-x OPEN Physical and environmental drivers of Paleozoic tetrapod dispersal across Pangaea Neil Brocklehurst1,2, Emma M. Dunne3, Daniel D. Cashmore3 &Jӧrg Frӧbisch2,4 The Carboniferous and Permian were crucial intervals in the establishment of terrestrial ecosystems, which occurred alongside substantial environmental and climate changes throughout the globe, as well as the final assembly of the supercontinent of Pangaea. The fl 1234567890():,; in uence of these changes on tetrapod biogeography is highly contentious, with some authors suggesting a cosmopolitan fauna resulting from a lack of barriers, and some iden- tifying provincialism. Here we carry out a detailed historical biogeographic analysis of late Paleozoic tetrapods to study the patterns of dispersal and vicariance. A likelihood-based approach to infer ancestral areas is combined with stochastic mapping to assess rates of vicariance and dispersal. Both the late Carboniferous and the end-Guadalupian are char- acterised by a decrease in dispersal and a vicariance peak in amniotes and amphibians. The first of these shifts is attributed to orogenic activity, the second to increasing climate heterogeneity. 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3AN, UK. 2 Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz-Institut für Evolutions- und Biodiversitätsforschung, Invalidenstraße 43, 10115 Berlin, Germany. 3 School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK. 4 Institut -

Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia

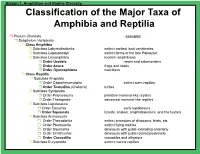

Station 1. Amphibian and Reptile Diversity Classification of the Major Taxa of Amphibia and Reptilia ! Phylum Chordata examples ! Subphylum Vertebrata ! Class Amphibia ! Subclass Labyrinthodontia extinct earliest land vertebrates ! Subclass Lepospondyli extinct forms of the late Paleozoic ! Subclass Lissamphibia modern amphibians ! Order Urodela newts and salamanders ! Order Anura frogs and toads ! Order Gymnophiona caecilians ! Class Reptilia ! Subclass Anapsida ! Order Captorhinomorpha extinct stem reptiles ! Order Testudina (Chelonia) turtles ! Subclass Synapsida ! Order Pelycosauria primitive mammal-like reptiles ! Order Therapsida advanced mammal-like reptiles ! Subclass Lepidosaura ! Order Eosuchia early lepidosaurs ! Order Squamata lizards, snakes, amphisbaenians, and the tuatara ! Subclass Archosauria ! Order Thecodontia extinct ancestors of dinosaurs, birds, etc ! Order Pterosauria extinct flying reptiles ! Order Saurischia dinosaurs with pubis extending anteriorly ! Order Ornithischia dinosaurs with pubis rotated posteriorly ! Order Crocodilia crocodiles and alligators ! Subclass Euryapsida extinct marine reptiles Station 1. Amphibian Skin AMPHIBIAN SKIN Most amphibians (amphi = double, bios = life) have a complex life history that often includes aquatic and terrestrial forms. All amphibians have bare skin - lacking scales, feathers, or hair -that is used for exchange of water, ions and gases. Both water and gases pass readily through amphibian skin. Cutaneous respiration depends on moisture, so most frogs and salamanders are -

An Early Late Triassic Long-Necked Reptile with a Bony Pectoral Shield and Gracile Appendages

An early Late Triassic long-necked reptile with a bony pectoral shield and gracile appendages JERZY DZIK and TOMASZ SULEJ Dzik, J. and Sulej, T. 2016. An early Late Triassic long-necked reptile with a bony pectoral shield and gracile appendages. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61 (4): 805–823. Several partially articulated specimens and numerous isolated bones of Ozimek volans gen. et sp. nov., from the late Carnian lacustrine deposits exposed at Krasiejów in southern Poland, enable a reconstruction of most of the skeleton. The unique character of the animal is its enlarged plate-like coracoids presumably fused with sterna. Other aspects of the skeleton seem to be comparable to those of the only known specimen of Sharovipteryx mirabilis from the latest Middle Triassic of Kyrgyzstan, which supports interpretation of both forms as protorosaurians. One may expect that the pectoral girdle of S. mirabilis, probably covered by the rock matrix in its only specimen, was similar to that of O. volans gen. et sp. nov. The Krasiejów material shows sharp teeth, low crescent scapula, three sacrals in a generalized pelvis (two of the sacrals being in contact with the ilium) and curved robust metatarsal of the fifth digit in the pes, which are unknown in Sharovipteryx. Other traits are plesiomorphic and, except for the pelvic girdle and extreme elongation of appendages, do not allow to identify any close connection of the sharovipterygids within the Triassic protorosaurians. Key words: Archosauromorpha, Sharovipteryx, protorosaurs, gliding, evolution, Carnian, Poland. Jerzy Dzik [[email protected]], Instytut Paleobiologii PAN, ul. Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warszawa, Poland and Wydział Biologii Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Centrum Nauk Biologiczno-Chemicznych, ul. -

A New Basal Sphenacodontid Synapsid from the Late Carboniferous of the Saar−Nahe Basin, Germany

A new basal sphenacodontid synapsid from the Late Carboniferous of the Saar−Nahe Basin, Germany JÖRG FRÖBISCH, RAINER R. SCHOCH, JOHANNES MÜLLER, THOMAS SCHINDLER, and DIETER SCHWEISS Fröbisch, J., Schoch, R.R., Müller, J., Schindler, T., and Schweiss, D. 2011. A new basal sphenacodontid synapsid from the Late Carboniferous of the Saar−Nahe Basin, Germany. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 56 (1): 113–120. A new basal sphenacodontid synapsid, represented by an anterior portion of a mandible, demonstrates for the first time the presence of amniotes in the largest European Permo−Carboniferous basin, the Saar−Nahe Basin. The new taxon, Cryptovenator hirschbergeri gen. et sp. nov., is autapomorphic in the extreme shortness and robustness of the lower jaw, with moderate heterodonty, including the absence of a greatly reduced first tooth and only a slight caniniform develop− ment of the second and third teeth. Cryptovenator shares with Dimetrodon, Sphenacodon, and Ctenospondylus, but nota− bly not with Secodontosaurus, enlarged canines and a characteristic teardrop outline of the marginal teeth in lateral view, possession of a deep symphyseal region, and a strongly concave dorsal margin of the dentary. The new find shows that sphenacodontids were present in the Saar−Nahe Basin by the latest Carboniferous, predating the record of sphenacodontid tracks from slightly younger sediments in this region. Key words: Synapsida, Sphenacodontidae, Carboniferous, Saar−Nahe Basin, Germany. Jörg Fröbisch [[email protected]], Department of Geology, The Field Museum, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605, USA and [joerg.froebisch@mfn−berlin.de], Museum für Naturkunde Leibniz−Institut für Evolu− tions− und Biodiversitätsforschung an der Humboldt−Universität zu Berlin, Invalidenstr.