Western Sahara) – Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 5 November 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Mainstreaming in State-Building: a Case Study of Saharawi Refugees and Their Foreign Representatives Sonia Rossetti University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives Sonia Rossetti University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rossetti, Sonia, Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives, Master of Arts (Research) thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3295 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. Erratum by author Page 61 Senia Bachir Abderahman is not the former president of the Saharawi Women Union, but a Saharawi student at the Mount Holyoke College in Norway. Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts (Research) from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Sonia Rossetti (Dott.ssa Giurisprudenza, University of Bologna Graduate Certificate in Australian Migration Law and Practice, ANU) Faculty of Arts School of History and Politics 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents iii List of Figures vi List of Tables vi Acronyms vii Glossary vii Abstract ix Acknowledgements xiii Chapter One: Introduction to the case study and methodology 1 1.1 Outlining the approach -

Forced Displacement – Global Trends in 2015

GLObaL LEADER ON StatISTICS ON REfugEES Trends at a Glance 2015 IN REVIEW Global forced displacement has increased in 2015, with record-high numbers. By the end of the year, 65.3 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or human rights violations. This is 5.8 million more than the previous year (59.5 million). MILLION FORCIBLY DISPLACED If these 65.3 million persons 65.3 WORLDWIDE were a nation, they would make up the 21st largest in the world. 21.3 million persons were refugees 16.1 million under UNHCR’s mandate 5.2 million Palestinian refugees registered by UNRWA 40.8 million internally displaced persons1 3.2 million asylum-seekers 12.4 24 86 MILLION PER CENT An estimated 12.4 million people were newly displaced Developing regions hosted 86 per due to conflict or persecution in cent of the world’s refugees under 2015. This included 8.6 million UNHCR’s mandate. At 13.9 million individuals displaced2 within people, this was the highest the borders of their own country figure in more than two decades. and 1.8 million newly displaced The Least Developed Countries refugees.3 The others were new provided asylum to 4.2 million applicants for asylum. refugees or about 26 per cent of the global total. 3.7 PERSONS MILLION EVERY MINUTE 183/1000 UNHCR estimates that REFUGEES / at least 10 million people On average 24 people INHABITANTS globally were stateless at the worldwide were displaced from end of 2015. However, data their homes every minute of Lebanon hosted the largest recorded by governments and every day during 2015 – some number of refugees in relation communicated to UNHCR were 34,000 people per day. -

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps

Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria HUMAN Human Rights in Western Sahara RIGHTS and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps WATCH Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-420-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-420-6 Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Map Of North Africa ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary...................................................................................................................... 2 Western Sahara ....................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Camps near Tindouf, Algeria ...................................................................... 8 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 12 To the UN Security Council .................................................................................... -

Evaluating the Palestinians' Claimed Right of Return

03 KENT (DO NOT DELETE) 1/21/2013 4:00 PM EVALUATING THE PALESTINIANS’ CLAIMED RIGHT OF RETURN ANDREW KENT* ABSTRACT This Article takes on a question at the heart of the longstanding Israeli-Palestinian dispute: did Israel violate international law during the conflict of 1947–49 either by expelling Palestinian civilians or by subsequently refusing to repatriate Palestinian refugees? Palestinians have claimed that Israel engaged in illegal ethnic cleansing, and that international law provides a “right of return” for the refugees displaced during what they call al-Nakbah (the catastrophe). Israel has disagreed, blaming Arab aggression and unilateral decisions by Arab inhabitants for the refugees’ flight, and asserting that international law provides no right of the refugees to return to Israel. Each side has scholars and advocates who have supported its factual and legal positions. This Article advances the debate in several respects. First, it moves beyond the fractious disputes about who did what to whom in 1947–49. Framed as a ruling on a motion for summary judgment, the Article assumes arguendo the truth of the Palestinian claim that the pre- state Jewish community and later Israel engaged in concerted, forced expulsion of those Palestinian Arabs who became refugees. Even granting this pro-Palestinian version of the facts, however, the Article concludes that such an expulsion was not illegal at the time and that international law did not provide a right of return. A second contribution of this Article is to historicize the international Copyright © 2012 by Andrew Kent. * Associate Professor, Fordham Law School; Faculty Advisor, Center on National Security at Fordham Law School. -

Western Sahara Refugees

Western Sahara Refugees BUILDING THE NATION - STATE ON “BORROWED” DESERT TERRITORY Introduction 2 a) To provide a brief historical overview of the conflict. b) To trace transformations whereby refugees became citizens on “borrowed” territory. c) To argue that the unequal relationship that characterizes the relationship between “beneficiary” and “recipient” of aid is challenged in the Sahrawi case. Introduction 3 Two factors facilitated self-government in the Sahrawi camps: 1. The policies of the host-state – Algeria. 2. The presence of political leadership with a vision to build a new society. The Sahrawi case inspired the work of Barbara Harrell- Bond and her critique of the humanitarian regime. Historical Overview 4 Western Sahara lies on the northwest corner of Africa. Rich in phosphate, minerals and fisheries. Possibly oil and natural gas. The people of Western Sahara are a mix of Arab tribes from Yemen (Bani Hassan), Berbers and sub-Saharan Africans. Speak Hassaniyyah a dialect of Arabic. Historical Overview 6 The everyday life of the individual revolved around the freeg – a small bedouin camp of around five khaymas or tents/families. Pastoral nomads (camels, goats) Cultivation Trade Oral tradition. Oral historian 7 Poet and oral historian 8 Historical Overview 9 Politically, the various Sahrawi tribes were represented by Ait Arb’een or the Assembly of Forty. During the scramble of Africa in 1884 and 1885 Western Sahara became a Spanish protectorate. The genesis of contemporary Sahrawi national consciousness may be traced to the latter half of the twentieth century. The Scramble of Africa 10 Historical Overview 11 The Polisario, the Sahrawi national liberation front, was formed on the 10th of May 1973 The Spanish finally withdrew their soldiers in 1975/76. -

1 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human Rights Developments Human rights violations were increasingly out in the open in 1995. Many Middle East governments decided they did not have to go to great lengths to conceal abusive practices in their battle against Islamist opponents and "enemies of the peace process." With the international community largely turning a blind eye, governments facing Islamist opposition groupsCviolent and nonviolentCliterally got away with murder. The violent groups they confronted were equally bold and bloodyCdeliberately killing civilians to punish or intimidate those who withheld support or were related, in any way, to the government. The Arab-Israeli peace process, jolted by the assassination of Israel's Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, dominated the political picture. Elsewhere in the region the aftermath of international armed conflicts and unresolved internal conflicts took other turns, with northeast Iraq the scene of internecine warfare between Kurdish groups and a Turkish invasion; continuing violence in and around Israeli-occupied south Lebanon; Iraq's failure to release information on the almost one thousand prisoners unaccounted for since it withdrew from Kuwait; Yemen's actions to stifle criticism in the wake of its civil war; and more delays in the process to resolve the seemingly intractable dispute between Morocco and the Polisario Front over the status of the Western Sahara. Nowhere was the conflict between an Islamist movement and a secular government more deadly than in Algeria, where tens of thousands died. Armed Islamist opposition groups in Algeria, as well as in Egypt and the Israeli-occupied territories, violated basic humanitarian norms by deliberately targeting civilians. -

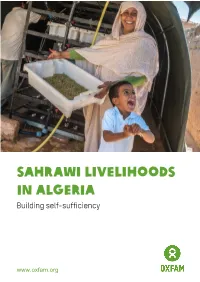

Sahrawi Livelihoods in Algeria: Building Self

Sahrawi livelihoods in algeria Building self-sufficiency www.oxfam.org OXFAM CASE STUDY – SEPTEMBER 2018 Over 40 years ago, Oxfam began working with Sahrawi refugees living in extremely harsh conditions in camps in the Saharan desert of western Algeria, who had fled their homes as a result of ongoing disputes over territory in Western Sahara. Since then, the Sahrawi refugees have been largely dependent on humanitarian aid from a number of agencies, but increasing needs and an uncertain funding future have meant that the agencies are having to adapt their programme approaches. Oxfam has met these new challenges by combining the existing aid with new resilience-building activities, supporting the community to lead self-sufficient and fulfilling lives in the arid desert environment. © Oxfam International September 2018 This case study was written by Mohamed Ouchene and Philippe Massebiau. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Meryem Benbrahim; the country programme and support teams; Eleanor Parker; Jude Powell; and Shekhar Anand in its production. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email Mohamed Ouchene ([email protected]) or Philippe Massebiau ([email protected]). This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged. -

EXILE, CAMPS, and CAMELS Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge Among Sahrawi Refugees

EXILE, CAMPS, AND CAMELS Recovery and adaptation of subsistence practices and ethnobiological knowledge among Sahrawi refugees GABRIELE VOLPATO Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr P. Howard Professor of Gender Studies in Agriculture, Wageningen University Honorary Professor in Biocultural Diversity and Ethnobiology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, UK Other members Prof. Dr J.W.M. van Dijk, Wageningen University Dr B.J. Jansen, Wageningen University Dr R. Puri, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Prof. Dr C. Horst, The Peace Research Institute, Oslo, Norway This research was conducted under the auspices of the CERES Graduate School Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 20 October 2014 at 11 a.m. in the Aula. Gabriele Volpato Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees, 274 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2014) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN 978-94-6257-081-8 To my mother Abstract Volpato, G. (2014). Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. With summaries in English and Dutch, 274 pp. -

The Sahrawi Refugees and Their National Identity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives The Sahrawi Refugees and their National Identity A qualitative study of how the Sahrawi Refugees present their national identity in online blogs Silje Rivelsrud Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies The Department of Political Science The Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITETET I OSLO May 2010 Acknowledgements The work on this thesis has been both challenging and rewarding, and would not have been possible without the support from a number of people. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Inger Skjelsbæk, for your encouragement and valuable feedback at every stage of my work with this thesis. I also want to thank Aashild Ramberg, for your patience and support. I am very grateful for the support and feedback I have received from my dad, Mari, Ida, Hanna, Anura and Marianne. Finally, I want to thank my husband, as well as all other friends and family for your patience, support and encouragement throughout my work on this thesis. 1 Western Sahara – Chronology compiled by Silje Rivelsrud 1884 Congress of Berlin. The European powers divide Africa. Spain commences its colonization of Western Sahara. 1960 UN Declaration 1514 (XV). Declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and people. 1963 Western Sahara included in the UN list of countries to be decolonized. 1967-73 Formation of Sahrawi resistance. 1973 Foundation of Polisario. 1975 The Green March. 1974/75 Spanish census and the plan to hold a referendum. -

Western-Sahara-FAQ.Pdf

At this very moment thousands of men, women and children are caught in the middle of a three decades old political conflict in the middle of the Sahara desert. Recently the Moroccan American Center for Policy (MACP) sponsored the visit of a delegation of former Sahrawi refugees to bring awareness about this forgotten humanitarian crisis. The Sahrawi delegation was made up of eight courageous individuals, all of whom managed to escape the refugee camps in Tindouf, Southern Algeria which are controlled by the Polisario Front, an Algerian-backed separatist group. Each had a personal story of how their lives, families and future have been affected— interrupted—by the politically motivated and cruel practices of the Polisario. However, they shared one common message: the separation of families and the oppression of the Sahrawi people must come to an end. F R E Q U E N T L Y A S K E D Q U E S T I O N S Q. What is the Polisario Front? A. The Poisario Front (a Spanish acronym for the “Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Rio de Oro”) was formed in 1973 as an independence movement against the Spanish colonization in the Sahara. After Spain relinquished the territory, the Polisario Front radically changed its mission and became the separatist group that it is today. The group was supported and armed by Algeria, Libya and Cuba in there respective attempts to undermine and destabilize United States ally, Morocco. Q. Are the Sahrawi people Moroccan? A. Yes. As early as 1578, the nomadic Bedouin tribes who inhabited the Sahara paid allegiance to the Moroccan Sultan (Moulay Ahmed El Mansour)—over 300 years before the arrival of the Spanish colonizers in 1884. -

The Right to Nationality in Africa

African Union African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights THE RIGHT TO NATIONALITY IN AFRICA African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights THE RIGHT TO NATIONALITY IN AFRICA Study undertaken by the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Internally Displaced Persons, pursuant to Resolution 234 of April 2013 and approved by the Commission at its 55th Ordinary Session, May 2014 2015 African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) This publication is available as a pdf on the ACHPR’s website under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, only in its entirety, as long as it is attributed to the ACHPR and used for non-commercial educational or public policy purposes. Published by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights 978-1-920677-81-7 ACHPR 31 Bijilo Annex Layout Kombo North District Western Region P.O. Box 673 Banjul The Gambia Tel: (220) 4410505 / 4410506 Fax: (220) 4410504 Email: [email protected] Web: www.achpr.org Designed and typeset by COMPRESS.dsl | www.compressdsl.com | v Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Methodology 3 1.3 Historical context 4 2. Origins of African laws on nationality 8 3. Legal definition of nationality 13 4. Nationality and the limitations of State sovereignty 15 4.1 The decisive role of the United Nations 16 4.2 Contribution of other regional systems 18 4.3 Implications for Africa 20 5. Nationality and African States’ laws and practices 21 5.1 Transition to independence 21 5.2 Determination of nationality for those born after independence 22 5.3 Recognition of the right to nationality 23 5.4 Nationality of origin 24 5.5 Nationality by acquisition 26 5.6 Multiple nationality 29 5.7 Discrimination 32 5.8 Loss and deprivation of nationality 33 5.9 Procedural rules 35 5.10 Nationality and succession of States 38 5.11 Regional citizenship 47 6. -

Inter-University Center for Legal Studies/Moroccan American Center Report on Sahrawi Refugees in Algeria

Group Rights and International Law: A Case Study on the Sahrawi Refugees in Algeria A Project of the Moroccan American Center for Policy Robert M. Holley, Executive Director Caitlin Dearing, Principal Author Jean AbiNader, Editor Group Rights and International Law: September 2009 A Case Study on the Sahrawi Refugees in Algeria INTER‐UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR LEGAL STUDIES 11 Group Rights and International Law TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword iv Abstract v THE MOROCCAN AMERICAN CENTER FOR POLICY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 The Moroccan American Center for Policy (MACP) is a non‐profit organization whose principal mission is to inform opinion makers, government INTRODUCTION 4 officials and an interested public in the United States about political and social developments in Morocco and the role being played by the Kingdom of THE ORIGINS OF THE SAHRAWI REFUGEES IN ALGERIA 5 Morocco in broader strategic developments in North Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. It is an initiative of His Majesty King THE ORIGINS OF INTERNATIONAL REFUGEE LAW 9 Mohammed VI that focuses on enhancing a broad range of Moroccan‐US relations. SPECIFIC RIGHTS IMPORTANT FOR SAHRAWI REFUGEES IN CAMPS IN ALGERIA 13 Background 14 MOROCCAN AMERICAN CENTER FOR POLICY 1220 L STREET NW Juridical Status 16 SUITE 411 WASHINGTON, DC 20005 Gainful Employment 18 (202) 587‐0855 HTTP://WWW.MOROCCANAMERICANPOLICY.ORG Welfare 20 Freedom of Movement and Documentation 23 Copyright © 2009 by the Moroccan American Center for Policy. All rights reserved. No part of THE EVOLUTION OF REFUGEE LAW: UNHCR AND this book may be reproduced, stored or distributed without the prior written consent of the THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 30 copyright holder.