1 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Mainstreaming in State-Building: a Case Study of Saharawi Refugees and Their Foreign Representatives Sonia Rossetti University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives Sonia Rossetti University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rossetti, Sonia, Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives, Master of Arts (Research) thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3295 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. Erratum by author Page 61 Senia Bachir Abderahman is not the former president of the Saharawi Women Union, but a Saharawi student at the Mount Holyoke College in Norway. Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts (Research) from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Sonia Rossetti (Dott.ssa Giurisprudenza, University of Bologna Graduate Certificate in Australian Migration Law and Practice, ANU) Faculty of Arts School of History and Politics 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents iii List of Figures vi List of Tables vi Acronyms vii Glossary vii Abstract ix Acknowledgements xiii Chapter One: Introduction to the case study and methodology 1 1.1 Outlining the approach -

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps

Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria HUMAN Human Rights in Western Sahara RIGHTS and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps WATCH Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-420-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-420-6 Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Map Of North Africa ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary...................................................................................................................... 2 Western Sahara ....................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Camps near Tindouf, Algeria ...................................................................... 8 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 12 To the UN Security Council .................................................................................... -

Policy Notes March 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MARCH 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 100 In the Service of Ideology: Iran’s Religious and Socioeconomic Activities in Syria Oula A. Alrifai “Syria is the 35th province and a strategic province for Iran...If the enemy attacks and aims to capture both Syria and Khuzestan our priority would be Syria. Because if we hold on to Syria, we would be able to retake Khuzestan; yet if Syria were lost, we would not be able to keep even Tehran.” — Mehdi Taeb, commander, Basij Resistance Force, 2013* Taeb, 2013 ran’s policy toward Syria is aimed at providing strategic depth for the Pictured are the Sayyeda Tehran regime. Since its inception in 1979, the regime has coopted local Zainab shrine in Damascus, Syrian Shia religious infrastructure while also building its own. Through youth scouts, and a pro-Iran I proxy actors from Lebanon and Iraq based mainly around the shrine of gathering, at which the banner Sayyeda Zainab on the outskirts of Damascus, the Iranian regime has reads, “Sayyed Commander Khamenei: You are the leader of the Arab world.” *Quoted in Ashfon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (2016). Khuzestan, in southwestern Iran, is the site of a decades-long separatist movement. OULA A. ALRIFAI IRAN’S RELIGIOUS AND SOCIOECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN SYRIA consolidated control over levers in various localities. against fellow Baathists in Damascus on November Beyond religious proselytization, these networks 13, 1970. At the time, Iran’s Shia clerics were in exile have provided education, healthcare, and social as Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was still in control services, among other things. -

Western Sahara Refugees

Western Sahara Refugees BUILDING THE NATION - STATE ON “BORROWED” DESERT TERRITORY Introduction 2 a) To provide a brief historical overview of the conflict. b) To trace transformations whereby refugees became citizens on “borrowed” territory. c) To argue that the unequal relationship that characterizes the relationship between “beneficiary” and “recipient” of aid is challenged in the Sahrawi case. Introduction 3 Two factors facilitated self-government in the Sahrawi camps: 1. The policies of the host-state – Algeria. 2. The presence of political leadership with a vision to build a new society. The Sahrawi case inspired the work of Barbara Harrell- Bond and her critique of the humanitarian regime. Historical Overview 4 Western Sahara lies on the northwest corner of Africa. Rich in phosphate, minerals and fisheries. Possibly oil and natural gas. The people of Western Sahara are a mix of Arab tribes from Yemen (Bani Hassan), Berbers and sub-Saharan Africans. Speak Hassaniyyah a dialect of Arabic. Historical Overview 6 The everyday life of the individual revolved around the freeg – a small bedouin camp of around five khaymas or tents/families. Pastoral nomads (camels, goats) Cultivation Trade Oral tradition. Oral historian 7 Poet and oral historian 8 Historical Overview 9 Politically, the various Sahrawi tribes were represented by Ait Arb’een or the Assembly of Forty. During the scramble of Africa in 1884 and 1885 Western Sahara became a Spanish protectorate. The genesis of contemporary Sahrawi national consciousness may be traced to the latter half of the twentieth century. The Scramble of Africa 10 Historical Overview 11 The Polisario, the Sahrawi national liberation front, was formed on the 10th of May 1973 The Spanish finally withdrew their soldiers in 1975/76. -

The 12Th Annual Report on Human Rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013)

The 12th annual report On human rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013) January 2014 January 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Genocide: daily massacres amidst international silence 8 Arbitrary detention and Enforced Disappearances 11 Besiegement: slow-motion genocide 14 Violations committed against health and the health sector 17 The conditions of Syrian refugees 23 The use of internationally prohibited weapons 27 Violations committed against freedom of the press 31 Violations committed against houses of worship 39 The targeting of historical and archaeological sites 44 Legal and legislative amendments 46 References 47 About SHRC 48 The 12th annual report on human rights in Syria (January 2013 – December 2013) Introduction The year 2013 witnessed a continuation of grave and unprecedented violations committed against the Syrian people amidst a similarly shocking and unprecedented silence in the international community since the beginning of the revolution in March 2011. Throughout the year, massacres were committed on almost a daily basis killing more than 40.000 people and injuring 100.000 others at least. In its attacks, the regime used heavy weapons, small arms, cold weapons and even internationally prohibited weapons. The chemical attack on eastern Ghouta is considered a landmark in the violations committed by the regime against civilians; it is also considered a milestone in the international community’s response to human rights violations Throughout the year, massacres in Syria, despite it not being the first attack in which were committed on almost a daily internationally prohibited weapons have been used by the basis killing more than 40.000 regime. The international community’s response to the crime people and injuring 100.000 drew the international public’s attention to the atrocities others at least. -

REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Forces Took Control of the Strategic Village of Kasab in Lattakia and Its Border Crossing with Turkey

north and the capital. A week after losing control of Yabroud, the opposition REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA forces took control of the strategic village of Kasab in Lattakia and its border crossing with Turkey. This conflict continues as SAF responded with heavy aerial 04 April 2014 bombardment and the redeployment of troops to the area. Meanwhile ISIL withdrew from many areas in northern and Western Aleppo (Hreitan, Azaz, Part I – Syria Mennegh) and Idleb by the end of February after months of clashes with rival Content Part I This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) fighters. The ISIL fighters have mostly moved to eastern Aleppo (Menbij, Al-Bab is now produced quarterly, replacing the monthly Overview and Jarablus), Ar-Raqqa, and Al-Hasakeh. This withdrawal was coupled with RAS of 2013. It seeks to bring together How to use the RAS? increased violence on the borders with Turkey. information from all sources in the region and Possible developments provide holistic analysis of the overall Syria Main events timeline Access: In early February a group of independent UN experts reported that crisis. Information gaps and data limitations deprivation of basic necessities and denial of humanitarian relief has become a While Part I focuses on the situation within Syria, Operational constraints widespread tactic utilised in the Syrian conflict. This includes deliberate attacks Part II covers the impact of the crisis on Humanitarian profile on medical facilities and staff; cutting off of water supplies and attacks on water neighbouring countries. Map - Conflict developments More information on how to use this document facilities; actions to destroy harvests and kill livestock – all of which obstructs Displacement profile can be found on page 2. -

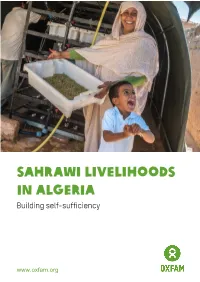

Sahrawi Livelihoods in Algeria: Building Self

Sahrawi livelihoods in algeria Building self-sufficiency www.oxfam.org OXFAM CASE STUDY – SEPTEMBER 2018 Over 40 years ago, Oxfam began working with Sahrawi refugees living in extremely harsh conditions in camps in the Saharan desert of western Algeria, who had fled their homes as a result of ongoing disputes over territory in Western Sahara. Since then, the Sahrawi refugees have been largely dependent on humanitarian aid from a number of agencies, but increasing needs and an uncertain funding future have meant that the agencies are having to adapt their programme approaches. Oxfam has met these new challenges by combining the existing aid with new resilience-building activities, supporting the community to lead self-sufficient and fulfilling lives in the arid desert environment. © Oxfam International September 2018 This case study was written by Mohamed Ouchene and Philippe Massebiau. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Meryem Benbrahim; the country programme and support teams; Eleanor Parker; Jude Powell; and Shekhar Anand in its production. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email Mohamed Ouchene ([email protected]) or Philippe Massebiau ([email protected]). This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged. -

EXILE, CAMPS, and CAMELS Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge Among Sahrawi Refugees

EXILE, CAMPS, AND CAMELS Recovery and adaptation of subsistence practices and ethnobiological knowledge among Sahrawi refugees GABRIELE VOLPATO Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr P. Howard Professor of Gender Studies in Agriculture, Wageningen University Honorary Professor in Biocultural Diversity and Ethnobiology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, UK Other members Prof. Dr J.W.M. van Dijk, Wageningen University Dr B.J. Jansen, Wageningen University Dr R. Puri, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Prof. Dr C. Horst, The Peace Research Institute, Oslo, Norway This research was conducted under the auspices of the CERES Graduate School Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 20 October 2014 at 11 a.m. in the Aula. Gabriele Volpato Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees, 274 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2014) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN 978-94-6257-081-8 To my mother Abstract Volpato, G. (2014). Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. With summaries in English and Dutch, 274 pp. -

JANUARY 1St 2014 $2.99

NINTH EDITION OF THE NEW ONLINE FREE AMERICAN JANUARY 1st 2014 $2.99 http://freeamerican.com Free American Jan. 1 2014 http://freeamerican.com 1 Publisher’s Corner Volume 9 January 1 - 2014 CRD Publishing PO Box 215 Seadrift, TX 77983 520-413-2397 Cell 512-767-4561 505-908-9498 http://freeamerican.com SKYPE Address: freeamerican69 www.facebook.com/freeamerican69 www.youtube.com/freeamerican69 Free American Hour and Magazine http://freeamerican.com Clayton Douglas, the Free American A Voice for Liberty for 25 years. Editorial Viewpoint Psycho Politics Updated The Free American remains committed to bringing the truth to the American people. We be- By Clayton R. Douglas lieve that in a free society, it is the job of the press to be the watchman of the government. It then Word Count 6235 falls upon the people, being fully informed, to decide what actions they must take to preserve and There has been a tremendous amount defend their liberty. The Free American is unabashedly, pro-American. Too many of our ancestors of work done on this website, my radio fought and died to protect our Constitution, the oldest in the world, to insure that we would retain show and the restoration of the Free Ameri- those liberties spelled out in our Bill of Rights. Based on the knowledge we have compiled over the can Magazine. Through cooperation with last years of publication, we believe there is a verifiable, well documented plan to force Americans other webmasters, activists, authors and the into a Global Government, complete with one world banking, a global ID system, an international first rate guests I have had the pleasure of police force, and a disarmed populous. -

Al Qaeda Rebels Slaughter Civilians in Adra

Syria Atrocities: US-NATO have “Blood on their Hands”. Western “Affiliated” Al Qaeda Rebels Slaughter Civilians in Adra By RT Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, December 17, 2013 RT New details of atrocities carried out by Islamist rebel fighters in the town of Adra, 20 kilometers north of Damascus, continue to pour in from survivors of the massacre there, in which reportedly at least 80 people lost their lives.”The decapitators” is how the Adra residents, who managed to flee the violence there, now call the people who currently have the town under their control. Adra, a town with a population of 20,000, was captured by Islamist rebels from the Al-Nusra front and the Army of Islam last week, following fierce fighting with the government forces. The town’s seizure was accompaniedmass by executions of civilians. RT Arabic has managed to speak to some of the eyewitnesses of the atrocities. Most of them have fled the town, leaving their relatives and friends behind, so they asked not to be identified in the report for security reasons. An Adra resident said he escaped from the town under“ a storm of bullets.” He later contacted his colleagues, who described how the executions of civilians were carried out by the militants. “They had lists of government employees on them,” the man told RT. “This means they had planned for it beforehand and knew who works in the governmental agencies. They went to the addresses they had on their list, forced the people out and subjected them to the so- called “Sharia trials.” I think that’s what they call it. -

“I Lost My Dignity”: Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in the Syrian Arab Republic

A/HRC/37/CRP.3 Distr.: Restricted 8 March 2018 English and Arabic only Human Rights Council Thirty-seventh session 26 February – 23 March 2018 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention. “I lost my dignity”: Sexual and gender-based violence in the Syrian Arab Republic Conference room paper of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic Summary Sexual and gender-based violence against women, girls, men, and boys has been a persistent issue in Syria since the uprising in 2011. Parties to the conflict resort to sexual violence as a tool to instil fear, humiliate and punish or, in the case of terrorist groups, as part of their enforced social order. While the immense suffering induced by these practices impacts Syrians from all backgrounds, women and girls have been disproportionally affected, victimised on multiple grounds, irrespective of perpetrator or geographical area. Government forces and associated militias have perpetrated rape and sexual abuse of women and girls and occasionally men during ground operations, house raids to arrest protestors and perceived opposition supporters, and at checkpoints. In detention, women and girls were subjected to invasive and humiliating searches and raped, sometimes gang- raped, while male detainees were most commonly raped with objects and sometimes subjected to genital mutilation. Rape of women and girls was documented in 20 Government political and military intelligence branches, and rape of men and boys was documented in 15 branches. Sexual violence against females and males is used to force confessions, to extract information, as punishment, as well as to terrorise opposition communities. -

The Sahrawi Refugees and Their National Identity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives The Sahrawi Refugees and their National Identity A qualitative study of how the Sahrawi Refugees present their national identity in online blogs Silje Rivelsrud Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies The Department of Political Science The Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITETET I OSLO May 2010 Acknowledgements The work on this thesis has been both challenging and rewarding, and would not have been possible without the support from a number of people. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Inger Skjelsbæk, for your encouragement and valuable feedback at every stage of my work with this thesis. I also want to thank Aashild Ramberg, for your patience and support. I am very grateful for the support and feedback I have received from my dad, Mari, Ida, Hanna, Anura and Marianne. Finally, I want to thank my husband, as well as all other friends and family for your patience, support and encouragement throughout my work on this thesis. 1 Western Sahara – Chronology compiled by Silje Rivelsrud 1884 Congress of Berlin. The European powers divide Africa. Spain commences its colonization of Western Sahara. 1960 UN Declaration 1514 (XV). Declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and people. 1963 Western Sahara included in the UN list of countries to be decolonized. 1967-73 Formation of Sahrawi resistance. 1973 Foundation of Polisario. 1975 The Green March. 1974/75 Spanish census and the plan to hold a referendum.