Western Sahara Refugees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Mainstreaming in State-Building: a Case Study of Saharawi Refugees and Their Foreign Representatives Sonia Rossetti University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives Sonia Rossetti University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rossetti, Sonia, Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives, Master of Arts (Research) thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3295 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. Erratum by author Page 61 Senia Bachir Abderahman is not the former president of the Saharawi Women Union, but a Saharawi student at the Mount Holyoke College in Norway. Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts (Research) from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Sonia Rossetti (Dott.ssa Giurisprudenza, University of Bologna Graduate Certificate in Australian Migration Law and Practice, ANU) Faculty of Arts School of History and Politics 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents iii List of Figures vi List of Tables vi Acronyms vii Glossary vii Abstract ix Acknowledgements xiii Chapter One: Introduction to the case study and methodology 1 1.1 Outlining the approach -

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps

Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria HUMAN Human Rights in Western Sahara RIGHTS and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps WATCH Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-420-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-420-6 Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Map Of North Africa ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary...................................................................................................................... 2 Western Sahara ....................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Camps near Tindouf, Algeria ...................................................................... 8 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 12 To the UN Security Council .................................................................................... -

1 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human Rights Developments Human rights violations were increasingly out in the open in 1995. Many Middle East governments decided they did not have to go to great lengths to conceal abusive practices in their battle against Islamist opponents and "enemies of the peace process." With the international community largely turning a blind eye, governments facing Islamist opposition groupsCviolent and nonviolentCliterally got away with murder. The violent groups they confronted were equally bold and bloodyCdeliberately killing civilians to punish or intimidate those who withheld support or were related, in any way, to the government. The Arab-Israeli peace process, jolted by the assassination of Israel's Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, dominated the political picture. Elsewhere in the region the aftermath of international armed conflicts and unresolved internal conflicts took other turns, with northeast Iraq the scene of internecine warfare between Kurdish groups and a Turkish invasion; continuing violence in and around Israeli-occupied south Lebanon; Iraq's failure to release information on the almost one thousand prisoners unaccounted for since it withdrew from Kuwait; Yemen's actions to stifle criticism in the wake of its civil war; and more delays in the process to resolve the seemingly intractable dispute between Morocco and the Polisario Front over the status of the Western Sahara. Nowhere was the conflict between an Islamist movement and a secular government more deadly than in Algeria, where tens of thousands died. Armed Islamist opposition groups in Algeria, as well as in Egypt and the Israeli-occupied territories, violated basic humanitarian norms by deliberately targeting civilians. -

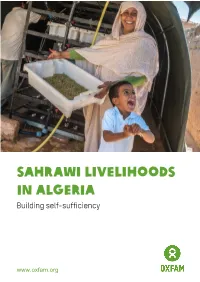

Sahrawi Livelihoods in Algeria: Building Self

Sahrawi livelihoods in algeria Building self-sufficiency www.oxfam.org OXFAM CASE STUDY – SEPTEMBER 2018 Over 40 years ago, Oxfam began working with Sahrawi refugees living in extremely harsh conditions in camps in the Saharan desert of western Algeria, who had fled their homes as a result of ongoing disputes over territory in Western Sahara. Since then, the Sahrawi refugees have been largely dependent on humanitarian aid from a number of agencies, but increasing needs and an uncertain funding future have meant that the agencies are having to adapt their programme approaches. Oxfam has met these new challenges by combining the existing aid with new resilience-building activities, supporting the community to lead self-sufficient and fulfilling lives in the arid desert environment. © Oxfam International September 2018 This case study was written by Mohamed Ouchene and Philippe Massebiau. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Meryem Benbrahim; the country programme and support teams; Eleanor Parker; Jude Powell; and Shekhar Anand in its production. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email Mohamed Ouchene ([email protected]) or Philippe Massebiau ([email protected]). This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged. -

EXILE, CAMPS, and CAMELS Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge Among Sahrawi Refugees

EXILE, CAMPS, AND CAMELS Recovery and adaptation of subsistence practices and ethnobiological knowledge among Sahrawi refugees GABRIELE VOLPATO Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis committee Promotor Prof. Dr P. Howard Professor of Gender Studies in Agriculture, Wageningen University Honorary Professor in Biocultural Diversity and Ethnobiology, School of Anthropology and Conservation, University of Kent, UK Other members Prof. Dr J.W.M. van Dijk, Wageningen University Dr B.J. Jansen, Wageningen University Dr R. Puri, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Prof. Dr C. Horst, The Peace Research Institute, Oslo, Norway This research was conducted under the auspices of the CERES Graduate School Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees Gabriele Volpato Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Monday 20 October 2014 at 11 a.m. in the Aula. Gabriele Volpato Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees, 274 pages. PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2014) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN 978-94-6257-081-8 To my mother Abstract Volpato, G. (2014). Exile, Camps, and Camels: Recovery and Adaptation of Subsistence Practices and Ethnobiological Knowledge among Sahrawi Refugees. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. With summaries in English and Dutch, 274 pp. -

The Sahrawi Refugees and Their National Identity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives The Sahrawi Refugees and their National Identity A qualitative study of how the Sahrawi Refugees present their national identity in online blogs Silje Rivelsrud Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies The Department of Political Science The Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITETET I OSLO May 2010 Acknowledgements The work on this thesis has been both challenging and rewarding, and would not have been possible without the support from a number of people. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Inger Skjelsbæk, for your encouragement and valuable feedback at every stage of my work with this thesis. I also want to thank Aashild Ramberg, for your patience and support. I am very grateful for the support and feedback I have received from my dad, Mari, Ida, Hanna, Anura and Marianne. Finally, I want to thank my husband, as well as all other friends and family for your patience, support and encouragement throughout my work on this thesis. 1 Western Sahara – Chronology compiled by Silje Rivelsrud 1884 Congress of Berlin. The European powers divide Africa. Spain commences its colonization of Western Sahara. 1960 UN Declaration 1514 (XV). Declaration on the granting of independence to colonial countries and people. 1963 Western Sahara included in the UN list of countries to be decolonized. 1967-73 Formation of Sahrawi resistance. 1973 Foundation of Polisario. 1975 The Green March. 1974/75 Spanish census and the plan to hold a referendum. -

Western-Sahara-FAQ.Pdf

At this very moment thousands of men, women and children are caught in the middle of a three decades old political conflict in the middle of the Sahara desert. Recently the Moroccan American Center for Policy (MACP) sponsored the visit of a delegation of former Sahrawi refugees to bring awareness about this forgotten humanitarian crisis. The Sahrawi delegation was made up of eight courageous individuals, all of whom managed to escape the refugee camps in Tindouf, Southern Algeria which are controlled by the Polisario Front, an Algerian-backed separatist group. Each had a personal story of how their lives, families and future have been affected— interrupted—by the politically motivated and cruel practices of the Polisario. However, they shared one common message: the separation of families and the oppression of the Sahrawi people must come to an end. F R E Q U E N T L Y A S K E D Q U E S T I O N S Q. What is the Polisario Front? A. The Poisario Front (a Spanish acronym for the “Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Rio de Oro”) was formed in 1973 as an independence movement against the Spanish colonization in the Sahara. After Spain relinquished the territory, the Polisario Front radically changed its mission and became the separatist group that it is today. The group was supported and armed by Algeria, Libya and Cuba in there respective attempts to undermine and destabilize United States ally, Morocco. Q. Are the Sahrawi people Moroccan? A. Yes. As early as 1578, the nomadic Bedouin tribes who inhabited the Sahara paid allegiance to the Moroccan Sultan (Moulay Ahmed El Mansour)—over 300 years before the arrival of the Spanish colonizers in 1884. -

Download the Full Report

HUMAN RIGHTS OFF THE RADAR Human Rights in the Tindouf Refugee Camps WATCH Off the Radar Human Rights in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Copyright © 2014 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-1654 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2014 978-1-62313-1654 Off the Radar Human Rights in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Freedom of Movement .............................................................................................................. 1 Freedom of Speech, Association, and Assembly ....................................................................... 2 The Use of Military Courts to Investigate and Try Civilians ......................................................... -

An Austrian Social Work Project in Western Sahara

Report Received 16 June 2020, accepted 10 December 2020 doi: 10.51741/sd.2021.60.2.181-186 Hubert Höllmüller An Austrian social work project in Western Sahara Western Sahara is a territory in northwest Africa, bordered by Morocco, Al- geria, Mauritania, and the Atlantic Ocean. In 1963, the United Nations asked Spain as the colonial power of Western Sahara, to decolonize the territory. But Spain did not answer this call, instead it handed the colony to the neighboring countries Morocco and Mauretania. In reaction, the Sahrawi people proclaimed the Democratic Arab Republic of Western Sahara or DARS. After the invasion of Morocco in the north and of Mauretania in the south, part of the people fled to Algeria and erected several refugee camps that exist to this day. According to Dreven, Poprask in Ramšak (2019), a military conflict ensued. Mauretania retreated in 1985 and Morocco took over this area and succeeded in permanently occupying about 80% of the Western Sahara, and the DARS was left with around 20%. Morocco brought in several hundred thousand of its citizens. To cut off the 20% rest of Western Sahara, a 2700 km long wall known as “the Berm,” surrounded by millions of land mines was built. In 1991, the United Nations brokered a ceasefire agreement and established a peacekeeping mission, the MINURSO, which has been monitoring the ceasefire and the buffer zone along the Berm for 29 years, but without any mandate to monitor the human rights situation in the occupied area. A referendum should have been carried out, but it hasn’t happened. -

Humanitarian Aid for the Sahrawi Refugees Living in the Tindouf Region

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES HUMANITARIAN AID OFFICE (ECHO) Decision to grant humanitarian aid Budget line 23 02 01 Title: Humanitarian aid for the Sahrawi refugees living in the Tindouf region Location of operation: ALGERIA Amount of Decision: EUR 8 000 000 Decision reference number: ECHO/DZA/BUD/2004/01000 Explanatory memorandum 1 - Rationale, needs and target population: 1.1. - Rationale Morocco and the Polisario Front have been fighting over the former Spanish colony of Western Sahara since 1975. A significant proportion of the Sahrawi population is living as refugees in the Tindouf region of south-west Algeria, and is heavily dependent on international aid. A conflict settlement plan adopted in 1991 by the UN Security Council provided for a referendum to let voters choose between independence and integration with Morocco. The plan made very little progress until 1997, when, at the instigation of James Baker, UN special envoy for the Western Sahara, the Polisario Front and Morocco signed the Houston accords. These enabled MINURSO (United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara) to resume the task of identifying voters, which had been suspended in May 1996. Unfortunately no breakthrough was achieved in the years that followed. In the absence of any agreement on the make-up of the electorate, and faced with 130 000 appeals, the UN proposed a variety of scenarios, none of which achieved consensus among all the parties. The latest Baker proposal1 is based on the framework agreement, with a somewhat altered content. The basis of this proposal (James Baker plan II) is extensive autonomy of the Sahrawis under Moroccan authority, with a referendum on self-determination to be held after 4 or 5 years. -

REPORTS Western Sahara a Thematic Report from the Norwegian Refugee Council, 2014

REPORTS Western Sahara A thematic report from the Norwegian Refugee Council, 2014 OCCUPIED COUNTRY, DISPLACED PEOPLE ›› 2 WESTERN SAHARA>BACKGROUND OCCUPIED COUNTRY, DISPLACED PEOPLE Western Sahara – Africa’s last colony More than 80 former colonies have diminished over the past few years is it to have right on your side if gained independence since the UN and is very unpredictable. Malnu- you do not get justice? While the Sahrawis wait for their rights to be respected, the international com- was founded, a process which has trition and anaemia are widespread affected more than one billion people, and the education sector is disinte- Western Sahara is clearly neglected munity has chosen to look the other way. The Sahrawis have learned through and in which the UN itself has played grating. For the government in exile by the international community. a crucial and driving role. the struggle is twofold: they have to Humanitarian assistance is decreas- bitter experience that without the help of powerful friends, it is of little use to meet the refugees’ immediate needs ing year by year, there is little media have justice on your side. Richard Skretteberg For most of us the decolonisation of at the same time as carrying out attention, and minimal will on the Editor Africa belongs to the history books, nation-building in exile. The refu- part of the international community and is viewed as one of the UN’s gees fear that dependence on aid to find a solution along the lines that Ever since Morocco invaded this thinly popu- crimination. There is now an increased The partition of the country is the result of greatest successes. -

Cycles of Crisis, Migration and the Formation of New Political Identities

June 2012 • 25 Cycles of crisis, migration and the formation of new political identities in Western Sahara Alice Wilson du CEPED s Centre Population et Développement UMR 196 CEPED, Université Paris Descartes, INED, IRD Working Paper http://www.ceped.org/wp Contact • Corresponding Author: Alice Wilson Division of Social Anthropology, University of Cambridge [email protected] Alice Wilson is a Junior Research Fellow at Homerton College, University of Cambridge, affiliated to the Division of Social Anthropology. She is a social anthropologist with research interests in the political and economic anthropology of North Africa and the Middle East. She has worked on statehood, tribes and sovereignty, specifically in the case of the state-in-exile of Western Sahara’s liberation movement. She holds a PhD in Social Anthropology (University of Cambridge, 2011). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Journée d’études of Équipe 2, CEPED, on the theme of crisis and migration in the global south, held at the Université Paris Descartes on 9th December 2011. Citation recommandée • Recommended citation Wilson A., « Cycles of crisis, migration and the formation of new political identities in Western Sahara », Working Paper du CEPED, number 25, UMR 196 CEPED, Université Paris Descartes, INED, IRD), Paris, June 2012. Available at http://www.ceped.org/wp CEPED • Centre Population et Développement UMR 196 CEPED, Université Paris Descartes, INED, IRD 19 rue Jacob 75006 PARIS, France http://www.ceped.org/ • [email protected] Les Working Papers du CEPED constituent des documents de travail portant sur des recherches menées par des chercheurs du CEPED ou associés.