Cycles of Crisis, Migration and the Formation of New Political Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and Insurgency in the Western Sahara

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues relat- ed to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrategic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and, • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of Defense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip reports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army participation in national security policy formulation. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press WAR AND INSURGENCY IN THE WESTERN SAHARA Geoffrey Jensen May 2013 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

Gender Mainstreaming in State-Building: a Case Study of Saharawi Refugees and Their Foreign Representatives Sonia Rossetti University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives Sonia Rossetti University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rossetti, Sonia, Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives, Master of Arts (Research) thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3295 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. Erratum by author Page 61 Senia Bachir Abderahman is not the former president of the Saharawi Women Union, but a Saharawi student at the Mount Holyoke College in Norway. Gender mainstreaming in state-building: a case study of Saharawi refugees and their foreign representatives A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts (Research) from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Sonia Rossetti (Dott.ssa Giurisprudenza, University of Bologna Graduate Certificate in Australian Migration Law and Practice, ANU) Faculty of Arts School of History and Politics 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents iii List of Figures vi List of Tables vi Acronyms vii Glossary vii Abstract ix Acknowledgements xiii Chapter One: Introduction to the case study and methodology 1 1.1 Outlining the approach -

Plan for Self-Determination for the People of Western Sahara

United Nations S/2007/210 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2007 Original: English Letter dated 16 April 2007 from the Permanent Representative of South Africa to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to write to transmit to you the proposal of the Frente Polisario for a mutually acceptable political solution that provides for the self- determination of the people of Western Sahara (see annex). I should be grateful if you would have the present letter and its annex circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Dumisani S. Kumalo Ambassador and Permanent Representative of the Republic of South Africa 07-30876 (E) 170407 *0730876* S/2007/210 Annex to the letter dated 16 April 2007 from the Permanent Representative of South Africa to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council [Original: English and French] Proposal of the Frente Polisario for a mutually acceptable political solution that provides for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara I. The Conflict of Western Sahara is a decolonisation question: 1. Included since 1965 on the list of the Non-Self-Governing territories of the UN Decolonisation Committee, Western Sahara is a territory of which the decolonisation process has been interrupted by the Moroccan invasion and occupation of 1975 and which is based on the implementation of the General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV) regarding the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples. 2. The UN General Assembly and the Security Council have identified this conflict as a decolonisation conflict between the Kingdom of Morocco and the Frente POLISARIO whose settlement passes by the exercise by the Saharawi people of their right to self-determination. -

Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps

Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria HUMAN Human Rights in Western Sahara RIGHTS and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps WATCH Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Morocco/Western Sahara/Algeria Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-420-6 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2008 1-56432-420-6 Human Rights in Western Sahara and in the Tindouf Refugee Camps Map Of North Africa ....................................................................................................... 1 Summary...................................................................................................................... 2 Western Sahara ....................................................................................................... 3 Refugee Camps near Tindouf, Algeria ...................................................................... 8 Recommendations ...................................................................................................... 12 To the UN Security Council .................................................................................... -

Western Sahara Refugees

Western Sahara Refugees BUILDING THE NATION - STATE ON “BORROWED” DESERT TERRITORY Introduction 2 a) To provide a brief historical overview of the conflict. b) To trace transformations whereby refugees became citizens on “borrowed” territory. c) To argue that the unequal relationship that characterizes the relationship between “beneficiary” and “recipient” of aid is challenged in the Sahrawi case. Introduction 3 Two factors facilitated self-government in the Sahrawi camps: 1. The policies of the host-state – Algeria. 2. The presence of political leadership with a vision to build a new society. The Sahrawi case inspired the work of Barbara Harrell- Bond and her critique of the humanitarian regime. Historical Overview 4 Western Sahara lies on the northwest corner of Africa. Rich in phosphate, minerals and fisheries. Possibly oil and natural gas. The people of Western Sahara are a mix of Arab tribes from Yemen (Bani Hassan), Berbers and sub-Saharan Africans. Speak Hassaniyyah a dialect of Arabic. Historical Overview 6 The everyday life of the individual revolved around the freeg – a small bedouin camp of around five khaymas or tents/families. Pastoral nomads (camels, goats) Cultivation Trade Oral tradition. Oral historian 7 Poet and oral historian 8 Historical Overview 9 Politically, the various Sahrawi tribes were represented by Ait Arb’een or the Assembly of Forty. During the scramble of Africa in 1884 and 1885 Western Sahara became a Spanish protectorate. The genesis of contemporary Sahrawi national consciousness may be traced to the latter half of the twentieth century. The Scramble of Africa 10 Historical Overview 11 The Polisario, the Sahrawi national liberation front, was formed on the 10th of May 1973 The Spanish finally withdrew their soldiers in 1975/76. -

1 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/MIDDLE EAST OVERVIEW Human Rights Developments Human rights violations were increasingly out in the open in 1995. Many Middle East governments decided they did not have to go to great lengths to conceal abusive practices in their battle against Islamist opponents and "enemies of the peace process." With the international community largely turning a blind eye, governments facing Islamist opposition groupsCviolent and nonviolentCliterally got away with murder. The violent groups they confronted were equally bold and bloodyCdeliberately killing civilians to punish or intimidate those who withheld support or were related, in any way, to the government. The Arab-Israeli peace process, jolted by the assassination of Israel's Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, dominated the political picture. Elsewhere in the region the aftermath of international armed conflicts and unresolved internal conflicts took other turns, with northeast Iraq the scene of internecine warfare between Kurdish groups and a Turkish invasion; continuing violence in and around Israeli-occupied south Lebanon; Iraq's failure to release information on the almost one thousand prisoners unaccounted for since it withdrew from Kuwait; Yemen's actions to stifle criticism in the wake of its civil war; and more delays in the process to resolve the seemingly intractable dispute between Morocco and the Polisario Front over the status of the Western Sahara. Nowhere was the conflict between an Islamist movement and a secular government more deadly than in Algeria, where tens of thousands died. Armed Islamist opposition groups in Algeria, as well as in Egypt and the Israeli-occupied territories, violated basic humanitarian norms by deliberately targeting civilians. -

1 Western Sahara As a Hybrid of A

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Western Sahara as a Hybrid of a Parastate and a State-in-exile: (Extra)territoriality and the Small Print of Sovereignty in a Context of Frozen Conflict AUTHORS Fernandez-Molina, I; Ojeda-García, R JOURNAL Nationalities Papers - The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity DEPOSITED IN ORE 30 October 2018 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/34557 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Western Sahara as a Hybrid of a Parastate and a State-in-exile: (Extra)territoriality and the Small Print of Sovereignty in a Context of Frozen Conflict Irene Fernández Molina, University of Exeter Raquel Ojeda-García, University of Granada Abstract This paper argues that the “declarative” parastate of the SADR claiming sovereignty over Western Sahara is better understood as a hybrid between a parastate and a state-in-exile. It relies more on external, “international legal sovereignty”, than on internal, “Westphalian” and “domestic” sovereignty. While its Algerian operational base in the Tindouf refugee camps makes the SADR work as a primarily extraterritorial state-in-exile de facto, its maintaining control over one quarter of Western Sahara’s territory proper allows it to at least partially meet the requirements for declarative statehood de jure. Many case-specific nuances surround the internal sovereignty of the SADR in relation to criteria for statehood, i.e. -

APPENDIX: REVIEWS of MICHAEL BRECHER's Books

APPENDIX: REVIEWS OF MICHAEL BRECHER’S BOOKS The Struggle for Kashmir (1953) “Of the three books under review [the others were George Fischer’s Soviet Opposition to Stalin and W. MacMahon Ball’s Nationalism and Communism in East Asia] the most interesting and suggestive is the one which from its title might appear the least important in the general feld of current international relationships. Dr. Michael Brecher’s The Struggle for Kashmir is a fne piece of research. Lucidly and attractively written, it offers a penetrating analysis of the course of the Kashmir dispute, of the reasons for the intense interest of both India and Pakistan in the disposition of the state, and of the opposed points of view of the governments of the two countries which remain as yet unreconciled. In particular, the Indian case has nowhere been so clearly and persuasively presented…. Pakistan con- tests the validity of the original accession [of the princely state, Jammu and Kashmir, to India in October 1947] on the ground of Indian conspiracy and pressure on the Maharaja [of Jammu and Kashmir], but Dr. Brecher’s careful evaluation of the evidence suggests that this thesis is unfounded…. The heart of the Kashmir dispute lies in the fact that it strikes at the foundation of the very existence of Pakistan and India alike…. If it be admitted that predominantly Muslim Kashmir may be included in India, then the reason for Pakistan’s existence disappears. For India, on the other hand, to admit this communal argument would be to forswear the inter-communal, secular structure of the Indian state: it would give © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 343 M. -

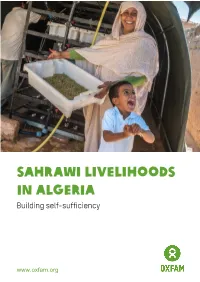

Sahrawi Livelihoods in Algeria: Building Self

Sahrawi livelihoods in algeria Building self-sufficiency www.oxfam.org OXFAM CASE STUDY – SEPTEMBER 2018 Over 40 years ago, Oxfam began working with Sahrawi refugees living in extremely harsh conditions in camps in the Saharan desert of western Algeria, who had fled their homes as a result of ongoing disputes over territory in Western Sahara. Since then, the Sahrawi refugees have been largely dependent on humanitarian aid from a number of agencies, but increasing needs and an uncertain funding future have meant that the agencies are having to adapt their programme approaches. Oxfam has met these new challenges by combining the existing aid with new resilience-building activities, supporting the community to lead self-sufficient and fulfilling lives in the arid desert environment. © Oxfam International September 2018 This case study was written by Mohamed Ouchene and Philippe Massebiau. Oxfam acknowledges the assistance of Meryem Benbrahim; the country programme and support teams; Eleanor Parker; Jude Powell; and Shekhar Anand in its production. It is part of a series of papers written to inform public debate on development and humanitarian policy issues. For further information on the issues raised in this paper please email Mohamed Ouchene ([email protected]) or Philippe Massebiau ([email protected]). This publication is copyright but the text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, permission must be secured and a fee may be charged. -

North Africa Issue 1, 2015

ISSUE 1, 2015 NORTH AFRICA The Thinker ACCORD is Ranked among Top Think Tanks in the World For the fi fth consecutive year, ACCORD has been recognised by the Global Go To Think Tank Index as one of the top-100 think tanks in the world. The 2014 Global Go To Think Tank Report was produced by the Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program (TTCSP) at the University of Pennsylvania, USA. ACCORD is proud to have been ranked out of over 6 600 think tanks globally, of which 467 are based in sub-Saharan Africa, in the following sub-categories: • 32nd in the category ‘Top Think Tanks Worldwide (Non-US)’ (p. 62) and is the highest ranked African institution in this category • 63rd in the category 'Top Think Tanks Worldwide (US and Non-US) (p. 66) • 6th in the category 'Top Think Tanks in Sub-Saharan Africa' (p. 69) • 23rd in the category 'Best Managed Think Tanks' (p. 118) • 31st in the category 'Best Use of Social Networks' (p. 134). Global Distribution of Think Tanks by Region The 2014 GlobalThe 2014 Think Go Report Tank To 27.53% These rankings pay testament to ACCORD’s Knowledge Production, Interventions and Training 30.05% departments, which strive to produce both 16.71% experientially-based and academically rigorous knowledge, derived from our 23 years in the 7.87% confl ict resolution fi eld, relevant to practitioners, governments, civil society and organisations 10.18% within Africa and throughout the world. 7.06% Now in its eighth year, the Global Go To Think 0.59% Tank Index has become an authoritative resource for individuals and institutions worldwide. -

Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation

REGENERATING REVOLUTION: Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation by Vivian Solana A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology in a Collaborative with the Women and Gender Studies Institute University of Toronto © Copyright by Vivian Solana, 2017 Regenerating Revolution: Gender and Generation in the Sahrawi Struggle for Decolonisation Vivian Solana Department of Anthropology in a Collaborative with the Women and Gender Studies Institute University of Toronto 2017 Abstract This dissertation investigates the forms of female labour that are sustaining and regenerating the political struggle for the decolonization of the Western Sahara. Since 1975, the Sahrawi national liberation movement—known as the POLISARIO Front—has been organizing itself, while in exile, into a form commensurable with the global model of the modern nation-state. In 1991, a UN mediated peace process inserted the Sahrawi struggle into what I describe as a colonial meantime. Women and youth—key targets of the POLISARIO Front’s empowerment policies—often stand for the movement’s revolutionary values as a whole. I argue that centering women’s labour into an account of revolution, nationalism and state-building reveals logics of long duree and models of female empowerment often overshadowed by the more “spectacular” and “heroic” expressions of Sahrawi women’s political action that feature prominently in dominant representations of Sahrawi nationalism. Differing significantly from globalised and modernist valorisations of women’s political agency, the model of female empowerment I highlight is one associated to the nomadic way of life that predates a Sahrawi project of revolutionary nationalism. -

Western Sahara Mission Notes

Peacekeeping_4_v11.qxd 2/2/06 5:06 PM Page 118 4.142.4 Western Sahara The United Nations Mission for the Referen- efforts to implement the referendum proposal, dum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) under- the Secretary-General appointed former US went a moderate restructuring in the course of secretary of state James Baker as his Personal 2005, in the context of deteriorating compli- Envoy. Baker was asked to work with the par- ance with agreements reached by Morocco and ties to the conflict to assess whether the settle- the Frente Popular para la Liberación de ment plan could be implemented in its exist- Saguia el-Hamra y de Río de Oro (Polisario). ing form, or whether adjustments could be Meanwhile, the political stalemate over the made to make it acceptable to both Morocco future of Western Sahara continued. In October and Polisario. 2005, the Secretary-General appointed Peter Following a number of initiatives aimed at Van Walsum as his Personal Envoy in a new breaking the deadlock, Baker presented in Janu- effort to break the deadlock. ary 2003 the “Peace Plan for Self-Determination MINURSO was established in 1991 in of the People of Western Sahara.” The Plan accordance with “settlement proposals” that provided for a five-year interim period during called for a cease-fire and the holding of a which governance responsibilities would be referendum on self-determination. In 1988, shared between Morocco and Polisario, fol- both the government of Morocco and the lowed by a choice of integration, autonomy, or Polisario agreed to the plan in principle.