ARTICLES Let's Talk About the Boteros: Law, Memory, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

They Hate US for Our War Crimes: an Argument for US Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights

UIC Law Review Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 4 2019 They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the ost-HumanP Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) Michael Drake Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Michael Drake, They Hate U.S. for Our War Crimes: An Argument for U.S. Ratification of the Rome Statute in Light of the Post-Human Rights Era, 53 UIC J. MARSHALL. L. REV. 1011 (2019) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol52/iss4/4 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEY HATE U.S. FOR OUR WAR CRIMES: AN ARGUMENT FOR U.S. RATIFICATION OF THE ROME STATUTE IN LIGHT OF THE POST-HUMAN RIGHTS ERA MICHAEL DRAKE* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................... 1012 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................ 1014 A. Continental Disparities ......................................... 1014 1. The International Process in Africa ............... 1014 2. The National Process in the United States of America ............................................................ 1016 B. The Rome Statute, the ICC, and the United States ................................................................................. 1020 1. An International Court to Hold National Leaders Accountable ...................................................... 1020 2. The Aims and Objectives of the Rome Statute .......................................................................... 1021 3. African Bias and U.S. -

A Small Slice of the Chicago Eight Trial

A Small Slice of the Chicago Eight Trial Ellen S. Podgor* The Chicago Eight trial was not the typical criminal trial, in part because it occurred at a time of society’s polarization, student demonstrations, and the rise of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Charges were levied against eight defendants, who were individuals that represented leaders in a variety of movements and groups during this time. This Essay examines the opening stages of this trial from the lens of a then relatively new criminal defense attorney, Gerald Lefcourt. It looks at his experiences before Judge Julius Hoffman and highlights how strong, steadfast criminal defense attorneys can make a difference in protecting key constitutional rights and values. Although judicial independence is crucial to a system premised on due process, it is also important that lawyers and law professors stand up to misconduct and improprieties. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 821 I. PROXIMITY AND SETTING .......................................................... 824 A. The Landscape ............................................................. 824 B. Attorney Gerald Lefcourt’s Role .................................. 828 II. ATTORNEY WITHDRAWALS AND SUBSTITUTIONS .................... 834 III. LESSONS LEARNED—RESPONDING TO MISPLACED JUDICIAL CONDUCT .............................................................................. 836 CONCLUSION ................................................................................ -

Timothy Leary's Last Interview

The REALIST Issue Number 138 - Spring, w o - r a g e ui scans of this entire issue found at: http://www.ep.tc/reall8t/138 Spring, 1998 Price: $2 Number Editor: Krassner Timothy L e a r y ’s Last Interview “Yeah, there was a period, I know exactly Editor's note: In September 1995, / was as source.” vhat it was, I was 15 or 16.1 was being sexu- signed by The Nation to tape a conversation “All right, h e r e ’s words. Fifteen years ago dly molested in my high school and actually with the ailing Timothy Leary. Several at a futurist conference you called yourself a icduccd by a wonderful sexy girl, much more months later, he died. The Nation had kept Nco-Tcchnological Pagan. What did you ■xperienced than I. And, whew! She opened it postponing publication, and eventually the mean by that?" jp! The great mystery of sex. Wow! At that editor admitted, “We blew it. ” The transcript “Neo has all the connotations of the futur ime I was going routinely to confession on is published here instead. ist stuff th a t’s coming along. Technological jaturday afternoon. But I had a date with denotes using machines, using electricity or “So, Tim, h e r e ’s a toast to 30 years of Rosemary that night. Sitting there in the dark light to create reality. There are tw o kinds of friendship.” :hurch. Then you go in and sa y , ‘Bless me, fa- technology. The machine — diesel, oil, metal, “And still counting. -

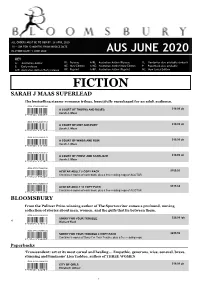

June 2020 Bloomsbury Subsheet

ALL ORDERS MUST BE TO UBD BY: 28 APRIL 2020 RI = SOR FOR 12 MONTHS FROM INVOICE DATE IN-STORE DATE: 1 JUNE 2020 AUS JUNE 2020 KEY A: Australian Author RI: Reissue A/RI: Australian Author/Reissue H: Hardcover also available (indent) E: Early release NE: New Edition A/NE: Australian Author/New Edition P: Paperback also available A/E: Australian Author/Early release RP: Reprint A/RP: Australian Author/Reprint NC: New Cover Edition FICTION SARAH J MAAS SUPERLEAD The bestselling steamy romance trilogy, beautifully repackaged for an adult audience. ,!7IB5C6-gafdjj!ISBN: 9781526605399 A COURT OF THORNS AND ROSES $19.99 pb Sarah J. Maas ......... ,!7IB5C6-gbhbgd!ISBN: 9781526617163 A COURT OF MIST AND FURY $19.99 pb Sarah J. Maas ......... ,!7IB5C6-gbhbha!ISBN: 9781526617170 A COURT OF WINGS AND RUIN $19.99 pb Sarah J. Maas ......... ,!7IB5C6-gbhbih!ISBN: 9781526617187 A COURT OF FROST AND STARLIGHT $19.99 pb Sarah J. Maas ......... ,!7IB4H2-jjjdag!ISBN: 9781472999306 ACOTAR ADULT 8 COPY PACK $159.92 Contains 2 copies of each book, plus a free reading copy of ACOTAR ......... ,!7IB4H2-jjjdbd!ISBN: 9781472999313 ACOTAR ADULT 16 COPY PACK $319.84 Contains 4 copies of each book, plus a free reading copy of ACOTAR ......... BLOOMSBURY From the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Sportswriter comes a profound, moving collection of stories about men, women, and the gulfs that lie between them. ,!7IB5C6-gcaadd!ISBN: 9781526620033 SORRY FOR YOUR TROUBLE $29.99 tpb H Richard Ford ......... ,!7IB4H2-jjjdca!ISBN: 9781472999320 SORRY FOR YOUR TROUBLE 8 COPY PACK $239.92 Contains 8 copies of Sorry For Your Trouble, plus a free reading copy ........ -

Neo-Conservatism and the State

NEO-CONSERVATISM AND THE STATE Reg Whitaker 'This is the Generation of that great LEVIATHAN, or rather (to speak more reverently) of that Mortal1 God, to which wee owe under the Immortal1 God, our peace and defence. For by this Authoritie, given him by every particular man in the Common-Wealth, he hath the use of so much Power and Strength conferred on him, that by terror thereof, he is inabled to forme the wills of them all, to Peace at home, and mutual ayd against their enemies abroad.' -Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan II:17 [I6511 If there is one characteristic of the neo-conservative political hegemony in America and Britain in the 1980s upon which both enthusiasts and most critics seemingly agree, it is that Reaganism and Thatcherism are pre- eminently laissez faire attacks on the state. From 'deregulation' in America to 'privatisation' in Britain, the message has seemed clear: the social democratic/Keynesian welfare state is under assault from those who wish to substitute markets for politics. Ancient arguments from the history of the capitalist state have risen from the graveyard to fasten, vampire-like, on the international crisis of capitalism itself. Once again the strident Babbitry of 'free enterprise versus the state' rings in the corridors of power, in editorial offices, in the halls of academe. Marshall McLuhan once offered the gnomic observation that we are fated to drive into the future while steering by the rear-view mirror. Or, as Marx wrote in regard to the French Revolution, revolutionaries '. anxiously conjure up the spirits -

Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law

The University of New Hampshire Law Review Volume 5 Number 3 Pierce Law Review Article 3 June 2009 Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law Arthur Austin Case Western Reserve University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/unh_lr Part of the Higher Education Commons, History Commons, Other Communication Commons, and the Other Rhetoric and Composition Commons Repository Citation Arthur Austin, Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law, 5 Pierce L. Rev. 367 (2007), available at http://scholars.unh.edu/unh_lr/vol5/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of New Hampshire Law Review by an authorized editor of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Parsing the Plagiary Scandals in History and Law ARTHUR AUSTIN ∗ I. INTRODUCTION In 2002 the history of History was scandal. The narrative started when a Pulitzer Prize winning professor was caught foisting bogus Vietnam War exploits as background for classroom discussion.1 His fantasy lapse pref- aced a more serious irregularity—the author of the Bancroft Prize book award was accused of falsifying key research documents.2 The award was rescinded. The year reached a crescendo with two plagiarism cases “that shook the history profession to its core.”3 Stephen Ambrose and Doris Kearns Goodwin were “crossover” celeb- rities: esteemed academics—Pulitzer winners—with careers embellished by a public intellectual reputation. -

JW Conspiracy Press

CONTACT: Nanda Dyssou, Publicist [email protected] (424)-226-6148 Conspiracy In The Streets The Extraordinary Trial of the Chicago Seven THE TRIAL THAT IS NOW A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE Reprinted to coincide with the release of the new Aaron Sorkin film, this book provides the political background of this infamous trial, narrating the utter craziness of the courtroom and revealing both the humorous antics and the serious politics involved Opening at the end of 1969—a politically charged year at the beginning of Nixon’s presidency and at the height of the anti-war movement—the Trial of the Chicago Seven (which started out as the Chicago Eight) brought together Yippies, antiwar activists, and Black Panthers to face conspiracy charges following massive protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, protests which continue to have remarkable contemporary resonance. The defendants—Rennie Davis, Dave Dellinger, John Froines, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Bobby Seale (the co-founder of the Black Panther Party who was ultimately removed from the trial, making it seven and not eight who were on trial), and Lee Weiner— openly lampooned the proceedings, blowing kisses to the jury, wearing their own judicial robes, and bringing a Viet Cong flag into the courtroom. Eventually the judge ordered Seale to be bound and gagged for insisting on representing himself. Adding to the theater in the courtroom an array of celebrity witnesses appeared, among them Timothy Leary, Norman Mailer, Arlo Guthrie, Judy Collins, and Allen Ginsberg (who provoked the prosecution by chanting “Om” on the witness stand). Author: Jon Wiener This book combines an abridged transcript of the trial with astute commentary by historian Format: Print, Ebook and journalist Jon Wiener, and brings to vivid life an extraordinary event which, like Woodstock, came to epitomize the late 1960s and the cause for free speech and the right Pages: 304 pages to protest—causes that are very much alive a half century later. -

Ai Weiwei at the Venice Biennale Jon Wiener

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 China Beat Archive 2011 Ai Weiwei at the Venice Biennale Jon Wiener Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, and the International Relations Commons Wiener, Jon, "Ai Weiwei at the Venice Biennale" (2011). The China Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012. 918. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/chinabeatarchive/918 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the China Beat Archive at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hinC a Beat Blog Archive 2008-2012 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Ai Weiwei at the Venice Biennale June 15, 2011 in Uncategorized by The China Beat | Permalink By Jon Wiener* At the world’s biggest art event this summer, the Venice Biennale, the world’s most famous imprisoned artist, Ai Weiwei, was not exactly neglected—but his case received virtually no official acknowledgment. Every two years the Italians invite dozens of nations to exhibit their leading artists, and this year the Biennale had 88 official “participating countries,” plus an additional 37 “collateral events.” And then there was an unofficial contribution, “Bye Bye Ai Weiwei,” written in six-foot tall white neon letters along the Giudecca canal, visible to all the passing vapporetti (water buses). Photo taken by the author But what did it mean? “This looks insulting,” the Guardian reviewer wrote, “like telling the artist to fuck off.” To some it seemed like bidding him farewell, accepting his imprisonment. -

John Lennon, “Revolution,” and the Politics of Musical Reception John Platoff Trinity College, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Trinity College Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Faculty Scholarship Spring 2005 John Lennon, “Revolution,” and the Politics of Musical Reception John Platoff Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/facpub Part of the Music Commons JOM.Platoff_pp241-267 6/2/05 9:20 AM Page 241 John Lennon, “Revolution,” and the Politics of Musical Reception JOHN PLATOFF A lmost everything about the 1968 Beatles song “Revolution” is complicated. The most controversial and overtly political song the Beatles had produced so far, it was created by John Lennon at a time of profound turmoil in his personal life, and in a year that was the turning point in the social and political upheavals of the 1960s. Lennon’s own ambivalence about his message, and conflicts about the song within the group, resulted in the release of two quite 241 different versions of the song. And public response to “Revolution” was highly politicized, which is not surprising considering its message and the timing of its release. In fact, an argument can be made that the re- ception of this song permanently changed the relationship between the band and much of its public. As we will see, the reception of “Revolution” reflected a tendency to focus on the words alone, without sufficient attention to their musical setting. Moreover, response to “Revolution” had much to do not just with the song itself but with public perceptions of the Beatles. -

Retracing the New Left: the SDS Outcasts Adam Mikhail

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Retracing the New Left: The SDS Outcasts Adam Mikhail Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES RETRACING THE NEW LEFT: THE SDS OUTCASTS By ADAM MIKHAIL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Adam Mikhail defended this thesis on November 12, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Neil Jumonville Professor Directing Thesis James P. Jones, Jr. Committee Member Kristine C. Harper Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Lala and Misso, who give and give and give. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my committee for all their help, not only during this thesis process, but throughout my time at Florida State University. I owe special thanks to my major professor, Dr. Neil Jumonville, who first introduced me to the New Left. He challenged me to think big, giving me constant encouragement along the way. I could not have hoped for a more understanding or supportive major professor. His kind words were never taken for granted. For an incredibly thorough editing of my thesis, I express my gratitude to Dr. Kristine Harper, who generously decorated this manuscript with ample amounts of red. -

CHAPTER 1 1. Ken Burns, “The Documentary Film: Its Role in The

Notes CHAPTER 1 1. Ken Burns, “The Documentary Film: Its Role in the Study of History,” text of speech delivered as a Lowell Lecture at Harvard College, 2 May 1991, 6. 2. Ken Burns, telephone interview with the author, 18 February 1993. 3. Ken Burns, interview with the author, 27 February 1996. 4. Neal Gabler, “History’s Prime Time,” TV Guide, 23 August 1997, 18. 5. Shelby Foote, Civil War: A Narrative (Fort Sumter to Perryville, Fredericksburg to Meridan, Red River to Appomattox), 3 vols. (New York: Random House, 1958-1974); David McCullough, The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge (New York: Touchstone, 1972); and Michael Shaara, The Killer Angels (New York: Ballantine, 1974). 6. Ken Burns, “Four O’Clock in the Morning Courage,” in Ken Burns’s The Civil War: Historians Respond, ed. Robert B. Toplin (New York: Oxford, 1996), 157. 7. Ken Burns quoted in “A Filmmaking Career” on the Thomas Jefferson (1997) website at <http://www.pbs.org/jefferson/making/KB_03.htm>. 8. The $3.2 million budget for The Civil War was comprised of contributions by the National Endowment for the Humanities ($1.3 million), General Motors ($1 million), the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and WETA-TV ($350,000), the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation ($350,000), and the MacArthur Foundation ($200,000). General Motors also provided an additional $600,000 for educational materials and promotional outreach. 9. Matt Roush, “Epic TV Film Tells Tragedy of a Nation,” USA Today, 21 September 1990, 1. 10. See Lewis Lord, “‘The Civil War’: Did Anyone Dislike It?” U.S. -

Opposition in South Africa's New Democracy

Opposition in South Africa’s New Democracy 28–30 June 2000 Kariega Game Reserve Eastern Cape Table of Contents Introduction 5 Prof. Roger Southall, Professor of Political Studies, Rhodes University Opening Remarks 7 Dr Michael Lange, Resident Representative, Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Johannesburg Opposition in South Africa: Issues and Problems 11 Prof. Roger Southall, Professor of Political Studies, Rhodes University The Realities of Opposition in South Africa: Legitimacy, Strategies and Consequences 27 Prof. Robert Schrire, Professor of Political Studies, University of Cape Town Dominant Party Rule, Opposition Parties and Minorities in South Africa 37 Prof. Hermann Giliomee, Formerly Professor in Political Studies, University of Cape Town Mr James Myburgh, Parliamentary Researcher, Democratic Party Prof. Lawrence Schlemmer, formerly Director of the Centre for Policy Studies, Graduate School of Business Administration, University of the Witwatersrand Political Alliances and Parliamentary Opposition in Post-Apartheid South Africa 51 Prof. Adam Habib, Associate Professor of Political Studies, University of Durban Westville Rupert Taylor, Associate Professor of Political Studies, Wits University Democracy, Power and Patronage: Debate and Opposition within the ANC and the 65 Tripartite Alliance since 1994 Dr Dale McKinley, Freelance Journalist, Independent Writer and Researcher The Alliance Under Stress: Governing in a Globalising World 81 Prof. Eddie Webster, Professor of Sociology, Wits University ‘White’ Political Parties and Democratic Consolidation in South Africa 95 Dr Eddie Maloka, Director, Africa Institute of South Africa 3 Table of Contents Opposition in the New South African Parliament 103 Ms. Lia Nijzink, Senior Researcher, Institute for a Democratic South Africa The Potential Constituency of the DA: What Dowries do the DP and the NNP Bring 113 to the Marriage? Prof.