Tudor Coinage B.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alliance Coin & Banknote World Coinage

Alliance Coin & Banknote Summer 2019 Auction World Coinage 1. Afghanistan - Silver 2 1/2 Rupee SH1300 (1921/2) KM.878, VF Est $35 2. Alderney - 5 Pounds 1996 Queen's 70th Birthday (KM.15a), a lovely Silver Proof Est $40 with mixed bouquet of Shamrocks, Roses and Thistle (etc.) on reverse 3. A lovely Algerian Discovery Set - A 9-piece set of Proof 1997 Algerian coinage, each Est $900-1,000 PCGS certified as follows: 1/4 Dinar PR-67 DCAM, 1/2 Dinar PR-69 DCAM, Dinar PR-69 DCAM, 2 Dinar PR-69 DCAM, 5 Dinar PR-69 DCAM, 10 Dinar PR-67 DCAM, 20 Dinar (bimetal Lion) PR-69 DCAM, 50 Dinar (bimetal Gazelle) PR-68 DCAM, completed by a lovely [1994] 100 Dinars bimetal Horse issue, PR-68 DCAM. All unlisted in Proof striking, thus comprising the only single examples ever certified by PCGS, with the Quarter and Half Dinar pieces completely unrecorded even as circulation strikes! Set of 9 choice animal-themed coins, and a unique opportunity for the North African specialist 4. Australia - An original 1966 Proof Set of six coins, Penny to Silver 50 Cents, housed in Est $180-210 blue presentation case of issue with brilliant coinage, the Half Dollar evenly-toned. While the uncirculated sets of the same date are common, the Proof strikings remain very elusive (Krause value: $290) 5. Australia - 1969 Proof Set of 6 coins, Cent to 50 Cents (PS.31), lovely frosted strikings Est $125-140 in original plastic casing, the Five Cent slightly rotated (Cat. US $225) 6. -

The Sovereign Grant and Sovereign Grant Reserve Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18

SOVEREIGN GRANT ACT 2011 The Sovereign Grant and Sovereign Grant Reserve Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 and Section 4 of the Sovereign Grant Act 2011 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 27 June 2018 HC 1153 © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us using the contact details available at www.royal.uk ISBN 978-1-5286-0459-8 CCS 0518725758 06/18 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Produced by Impress Print Services Limited. FRONT COVER: Queen Elizabeth II and The Duke of Edinburgh visit Stirling Castle on 5th July 2017. Photograph provided courtesy of Jane Barlow/Press Association. CONTENTS Page The Sovereign Grant 2 The Official Duties of The Queen 3 Performance Report 9 Accountability Report: Governance Statement 27 Remuneration and Staff Report 40 Statement of the Keeper of the Privy Purse’s Financial Responsibilities 44 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of 46 Parliament and the Royal -

The Chapels Royal of Britain. Iv

THE CHAPELS ROYAL OF BRITAIN THE CHAPELS ROYAL OF BRITAIN. IV. CHAPEL ROYAL, WHITEHALL. BY J. CRESSWELL RoscAMP, M.E. "Sir, you Must no more call it York Place: that is past,. For since the Cardinal fell, that title's lost ; 'Tis now the King's, and call'd-Whitehall." HITEHALL derived its name from the old Palace that stood W there till it was destroyed by fire in 1698. At the present time it is principally known from being the headquarters of aU the various offices connected with the Government and for the Horse Guard's building which was designed by Kent and is beautifully proportionate. The Palace of Whitehall was original! y known as " York House,'"~ and was the London residence of the Archbishops of York till •~ it was delivered and demised to the King (Henry VIII) by Charter February 7 (1529), on the disgrace of Cardinal Wolsey, Arch bishop of York, and was t,hen called Whitehall." It was built in 1240 by Hubert, Earl of Kent, and soon afterwards became the property of the Friars Predicant of Black Friars (Dominicans). who in 1248 sold it to Walter de Grey, Archbishop of York; and from that time to the fall of Wolsey it belonged to the See of York. Cll:rdinal Wolsey built much on to it including a Chapel, and it assumed under his ambitious tenure a splendour equal to, if not. surpassing, that of any Royal residence. The Cardinal had a passion for architecture and building, and loved pomp and magnificence, and thus it is not surprising to find his having made great additions, as he did at Oxford and Hampton Court. -

N THEREINACHC0.,Lnc

tecf 6y^ IsS Zs^V^ v v V V N Embroidery design for butterflies for use lines in on wo ist.B, lingerie, children's etc. the butterflies should clothes, ATI the METHOD OF TRANSFERRING. bo outlined, or if n handsomer single with French stem or development is desired cover tlie lines D^solve a half of whipping stitch. On lingerie materials the dots in teaspoonful washing powder or a small piece of soap in tv/o-thirda of a glass of Ijc&vorked in the wings of the butterflies could "crater. To this a eyelet. If the butterflies axe embroidered in add tablespoonful of ammonia. Place the material on which the transfer is to be made SET*iuimJ should colors, shades that liunnonizp on a Uo wed. xyifch the biie^ hard, onrooth surface, Saturate the back of the design with the al>ove solution, pla^e the design f«co down on the material, laying a stieet of thick paper over the back of the hold with one and design; ?irm'.y &and with the bowl of a Bpoca pib, with pressure, fronl vou. By following these diregions barefulljf some years ago in Paris, and appears' in one when it suits her and Iier cos- place. Th* two tutne. Yeomen of the Guard Incidentally, she :;iys tl.e < .1- JOIN lift the brass platter from the table ored is to IN wis be regarded merely a.- OBSERVANCE ami inarch to the head the a of lino of matter of decoration, rather than a artitlcial women. They are followed by the hair. -

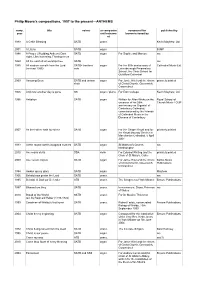

Philip Moore's Compositions, 1957 to the Present—ANTHEMS

Philip Moore's compositions, 1957 to the present—ANTHEMS comp. title voices accompanim composed for published by year ent/instrume /commissioned by nt 1988 A Celtic Blessing SATB unacc. Kevin Mayhew, Ltd 2001 A Litany SATB organ SJMP 1998 A Prayer (Wedding Anthem) Dark SATB organ For Sophie and Marcus ms night, Lilac humming, Flowing rivers 1959 All the earth shall worship thee SATB ms 1980 All wisdom cometh from the Lord SATB+ baritone organ For the 50th anniversary of Cathedral Music Ltd (revised 1985) solo Lanesborough Preparatory School, the Choir School for Guildford Cathedral 2009 Amazing Grace SATB and unison organ For Jamie Hitel and the choirs privately printed choir of Christ Church, Greenwich, Connecticut 1966 And now another day is gone SS organ / piano For Eton College Kevin Mayhew, Ltd 1986 Antiphon SATB organ Written for Allan Wicks on the Royal School of occasion of his 25th Church Music / OUP anniversary as Organist of Canterbury Cathedral; commissioned by the Friends of Cathedral Music in the Diocese of Canterbury 2007 As the Father hath loved me SATB organ For the Chapel Royal and for privately printed the Royal Maundy Service in Manchester Cathedral, 5 April 2007 1983 At the round earth's imagined corners SATB organ St Matthew's Church, ms Northampton 2010 Ave maris stella SSA violin For Edward Whiting and the privately printed Choir of St Mary’s, Calne 2009 Ave verum corpus SATB organ For Jamie Hitel and the choirs Banks Music of Christ Church, Greenwich, Publications Connecticut 1994 Awake up my glory SATB organ Mayhew 1966 Behold now praise the Lord SATB unacc. -

Roll out the Red Carpet P.J

Roll out the Red Carpet P.J. Salter Pat Salter worked at the Guildhall Museum Rochester and at MALSC for over 20 years. She is a well known author and works include A Man of Many Parts - Edwin Harris 1859 – 1938; Pat is also a FOMA Vice President. Roll out the Red Carpet, was originally published in The Clock Tower, the journal of the Friends of Medway Archives (FOMA) from May 2105 to May 2017 inclusive. The Clock Tower can be found on the FOMA website at http://foma-lsc.org/journal.html; the last two issues are password protected for FOMA members. Roll out the Red Carpet is a compilation of work originally undertaken by Pat for an exhibition at the Medway Archives in Strood, Kent, and gives a fascinating insight into royal visits to the Medway Towns over the centuries, from Anglo Saxon times right up to the present day. Thanks to Rob Flood and Philip Dodd for helping to make publication possible. Introduction The red carpet has been rolled out, literally or metaphorically, for royal visitors to the Medway area for centuries. However, the red carpet has not always been a celebratory one. Wars, sieges, rebellions and invasions have been occasioned by, or resulted in, carpets of blood. The Medway area has been inhabited since ancient times but the first royal visitor that we know of, with any certainty, was Aethelbert, King of Kent, in 604 and the latest, at the time of writing, that of the Princess Royal in March 2011. Chapter 1: Anglo Saxons The admirable Bede described Aethelberht, King of Kent as an able, powerful, and open-minded ruler who had a Christian Queen [Berta] unrestrained in her religious faith and practice and had the cathedral church of St Andrew built at Rochester from its foundations. -

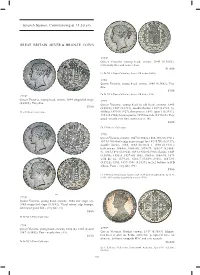

Seventh Session, Commencing at 11.30 Am

Seventh Session, Commencing at 11.30 am GREAT BRITAIN SILVER & BRONZE COINS 1631* Queen Victoria, young head, halfcrown, 1876 (S.3889). Gold and grey toned, good extremely fi ne. $500 Ex Fulton Collection with A.H.Baldwin envelope. 1628* Queen Victoria, young head, crown, 1845 (S.3882). Cleaned, nearly very fi ne. $150 Private purchase from I.S.Wright. part 1632* Queen Victoria, young head, shillings, 1839 WW (S.3902), 1852 (S.2904), 1865 die no. 46 (S.3905), 1872 die no. 139 1629* (S.3906A), 1885 (S.3907). The third good very fi ne, others Queen Victoria, Gothic crown, 1847 (S.3883). Attractive extremely fi ne - uncirculated, the fi rst rare. (5) light toning, underlying brilliance, nearly uncirculated. $800 $3,000 The second ex Noble Numismatics Sale 71 (lot 1888), the fi rst from Queen Victoria Coins. 1633* Queen Victoria, young head, sixpence, 1844 small 44 (S.3908). Good extremely fi ne. 1630* $200 Queen Victoria, Gothic crown, 1847 (S.3883). Scratches in obverse fi elds, toned, some brilliance on the reverse, extremely fi ne/good extremely fi ne. $1,500 Ex Status Sale 182 (lot 3166). 174 1637* 1634 * Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, crown, 1887 (S.3921). Deep Queen Victoria, young head, sixpences, 1871 die no. 23, grey tone, underlying brilliance, uncirculated. 1878 die no. 67 (S.3910). Toned, extremely fi ne; good $250 extremely fi ne. (2) $150 Ex Fulton Collection. 1638 Queen Victoria, Jubilee head, crown, 1887, double fl orin, 1887 Arabic 1 type, halfcrown, 1887 (S.3921, 3923, 3924). Toned, good very fi ne - extremely fi ne. -

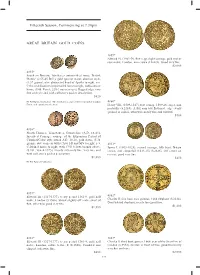

Fifteenth Session, Commencing at 7.30Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

Fifteenth Session, Commencing at 7.30pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS 4859* Edward IV, (1461-70, fi rst reign) light coinage, gold ryal or rose-noble, London, mm crown (1468-9). Good very fi ne. $2,000 4855* Southern Britain, Atrebates uninscribed issue, British 'Remic' (c.55-45 B.C.), gold quarter stater, abstract style, (1.37 grams), obv. abstracted head of Apollo to right, rev. Celticized disjointed triple tailed horse to right, dahlia above horse, (S.48, Van A. 220-1 notes as rare). Ragged edge, very fi ne and rare and with collector's packet description. $420 Ex Pat Boland Collection. The Atrebates occupied the territory that is today 4860* Essex, and counties to the west. Henry VIII, (1509-1547), fi rst coinage 1509-26, angel, mm portcullis (S.2265). A full coin but fl attened, edge evenly grained or milled, otherwise nearly fi ne and unusual. $500 4856* North Thames, Trinovantes, Cunobeline (A.D. 10-43), Inscribed Coinage, coinage of the Expansion Period of Classical/Celtic style issued A.D. 10-20, gold stater, (5.34 grams), obv. corn ear with CA to left and MV to right, rev. 4861* Celticized horse to right, with CVN below, branch above, James I, (1603-1625), second coinage, fi fth bust, Britain (S.281, Van A.1925). Nearly extremely fi ne, very rare and crown, mm cinquefoil (1613-15) (S.2626). Off centre on with collector's packet description. reverse, good very fi ne. $1,000 $450 Ex Pat Boland Collection. 4857* Edward III, (1327-1377), treaty period 1361-9, gold half 4862* noble, London (S.1506). -

Seventh Session, Commencing at 11.30 Am

Seventh Session, Commencing at 11.30 am GREAT BRITAIN SILVER & BRONZE COINS 1795* Queen Victoria, young head, crown, 1845 (S.3882). Extremely fi ne and scarce thus. $1,000 Ex Dr V.J.A.Flynn Collection, from a UK dealer (£400). 1796 Queen Victoria, young head, crown, 1845 (S.3882). Very fi ne. $100 Ex Dr V.J.A.Flynn Collection, from a UK dealer (£38). 1792* Queen Victoria, young head, crown, 1844 cinquefoil stops 1797 (S.3882). Very fi ne. Queen Victoria, young head to old head, crowns, 1845 $300 (S.3882); 1887 (S.3921), double fl orins, 1887 (S.3922, 3), Ex C.R.Deane Collection. shilling, 1890 (S.3927), threepences, 1893, open 3 (S.3931), 1901 (S.3942), bronze penny, 1895 low tide (S.3961A). Very good - nearly very fi ne, some scarce. (8) $200 Ex C.R.Deane Collection. 1798 Queen Victoria, crowns, 1847 (S.3882), 1888-1892 (S.3921), 1893-1900 (both edge years except for 1899 LXI) (S.3937); double florins, 1888, 1888 inverted 1, 1890 (S.3923); halfcrowns, 1844-6, 1848-50, 1874-79, 1881-7 (S.3888- 9), 1887-1892 (S.3924), 1893-1900 (S.3938); fl orins, 1849 (S.3890), 1852-5, 1857-60, 1862, 1865-6, 1868-76, 1879 with die no, 1879-81, 1883-7 (S.3891-3901), 1887-91 (S.3925), 1893, 1897-1901 (S.3939), in 2x2 holders in HB album. Poor - very fi ne. (98) $900 Ex C.R.Deane Collection, fl orins 1849-1859 from Huddersfi eld, 14.03.78 (1854, £95), mainly acquired in the late 1970s. -

Wakefield Cathedral Choir - Składa Się Z Chłopców, Dziewcząt I Mężczyzn

Wakefield Cathedral Choir - składa się z chłopców, dziewcząt i mężczyzn. Większość chłopców kształci się w Queen Elizabeth Grammar School i otrzymuje stypendia chóralne. Chórzystki dziewczęce zostały wprowadzone w 1992 r. krótko po ich wprowadzeniu w katedrze w Salisbury. Chór występuje podczas chóralnych wieczorów we wtorek, środę, czwartek i od czasu do czasu w piątek oraz podczas niedzielnych nabożeństw: parafialnej Eucharystii, uroczystej Eucharystii i Evensong, czyli wieczornych nabożeństw. Zazwyczaj chłopcy i dziewczęta śpiewają osobno, sami lub z mężczyznami. Chłopcy, dziewczęta i mężczyźni podejmują pełny program usług, koncertów, nagrań i występów telewizyjnych. Pomimo różnych dodatkowych działań opisanych poniżej, które umożliwiają szersze rozpowszechnianie posługi i kultu Katedry, głównym zadaniem Chóru pozostaje i zawsze pozostanie oferta najwyższej jakości muzyki w regularnych usługach Katedry. W latach 70. Chór Katedralny brał czynny udział w Festiwalu Katedr Zachodnich (razem z chórami z Bradford i Sheffield). Od 1981 roku współpracuje z chórami Ripon Cathedral i Leeds Parish Church w Yorkshire Three Choirs Festival. Po utworzeniu diecezji Leeds trzy katedry (Bradford, Ripon i Wakefield) z diecezji utworzyły Festiwal Chórów Katedralnych Yorkshire. Pierwszy festiwal Yorkshire Girls 'Choirs Festival odbył się w Wakefield w 1998 roku (dziewczęta i mężczyźni z York Minster, Ripon, Sheffield and Wakefield Cathedrals i Leeds Parish Church). Wycieczki krajowe rozpoczęły się w 1975 r. od wizyty w katedrze w Wells; po tym nastąpiły wycieczki do Winchester, Salisbury, Chichester, Portsmouth, Arundel i St. Paul's Cathedral. Chór odwiedził Niemcy, Francję, Amerykę (Boston przez Nowy Jork i Baltimore do Waszyngtonu), Szkocję, Salzburg, Rzym, Toskania, Wyspę Man i Belgię. Pierwsza zagraniczna trasa dziewczęca z mężczyznami odbyła się w Szwecji w 2001 roku, a następnie do Chichester, Nadrenii, katedry w Exeter i Nowego Jorku, w tym w kościele St. -

Some Scottish Ceremonial Coins

SOME SCOTTISH CEREMONIAL COINS . STEWARTH N bIA y , F.S.A.SCOT. INTRODUCTION IN later medieval times special coins were only rarely struc ceremoniar kfo l purposes. When pieces were require presentationdfor offeringor , almsor , currenthe , t coin of the day was generally used. Pictorial and commemorative medals were a creation of the Renaissance, from which time pieces with non-monetary functions became gradually dissociated fro typee mformth d s an coinagef o s . Unti e appearancth l f medale sixteento e th n si h century, ther e verw ar e yfe examples in the Scottish series of coins or coin-like pieces which can make any claim to have been struck for other than normal monetary purposes. In the following pages, four items which may come into this category are discussed. One, the James groat V f thaI o s ti , species whic fabrin hi desigd can n conforms wit ordinare hth y associatee b n currencca t i dday s t it wit f bu ,y o particulah a r occasio almsgivinf no g by documentary evidence secondA . sovereige th , n medallio Jamef no s a IIIs i , heavy presentation piece, unlik existiny ean g Scottish perioe cointh t witf so dbu h coin-like types and inscriptions.1 Another gold piedfort, the James IV angel, is probably not a pattern for coinage and must be presumed to have been struck for some purpose unrelate e ordinarth o t d y currency e lasTh t . piece e angeth ,f o l Charleexampln a survivas e i th , sI archaif n ea o f lo c typ speciacoif a eo r nfo l royal ceremony. -

The Queen's Year

THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST The Queen’s Year Spring Commonwealth Observance Day The Royal Maundy Service Easter Court The Queen’s Birthday Commonwealth Observance Day The first annual occurrence of the royal year is Commonwealth Day, which is celebrated throughout the Commonwealth of Nations on the second Monday of March. It is marked by the colourful Observance for Commonwealth Day held in Westminster Abbey. The ceremony begins with a procession of flag bearers, each representing one of the 53 member states, and includes a lively assortment of musical performances, readings from some of the Commonwealth’s faiths, and speeches from The Queen, as Head of the Commonwealth, and the Secretary-General. It is attended by dignitaries, High Commissioners, religious leaders, citizens and school children from across the Commonwealth. A reception is held at Marlborough House, the Headquarters of the Commonwealth Secretariat, and is usually attended by The Queen. The day is also marked by a special recorded message from Her Majesty to the people of the Commonwealth, continuing a tradition begun by her father, King George VI. Each year Commonwealth Day has a theme – in 2010 it was Science, Technology and Society . The day also usually marks the beginning of the Commonwealth Games Queen’s Baton Relay, which has anticipated every Commonwealth Games since 1958. The baton for the 2010 Games will go on the longest ever relay, travelling throughout the entire Commonwealth and then through all 28 states of India before arriving in Delhi for the opening ceremony. The Royal Maundy Service The Royal Maundy Service occurs on Maundy Thursday, the last Thursday before Easter.