Roll out the Red Carpet P.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alliance Coin & Banknote World Coinage

Alliance Coin & Banknote Summer 2019 Auction World Coinage 1. Afghanistan - Silver 2 1/2 Rupee SH1300 (1921/2) KM.878, VF Est $35 2. Alderney - 5 Pounds 1996 Queen's 70th Birthday (KM.15a), a lovely Silver Proof Est $40 with mixed bouquet of Shamrocks, Roses and Thistle (etc.) on reverse 3. A lovely Algerian Discovery Set - A 9-piece set of Proof 1997 Algerian coinage, each Est $900-1,000 PCGS certified as follows: 1/4 Dinar PR-67 DCAM, 1/2 Dinar PR-69 DCAM, Dinar PR-69 DCAM, 2 Dinar PR-69 DCAM, 5 Dinar PR-69 DCAM, 10 Dinar PR-67 DCAM, 20 Dinar (bimetal Lion) PR-69 DCAM, 50 Dinar (bimetal Gazelle) PR-68 DCAM, completed by a lovely [1994] 100 Dinars bimetal Horse issue, PR-68 DCAM. All unlisted in Proof striking, thus comprising the only single examples ever certified by PCGS, with the Quarter and Half Dinar pieces completely unrecorded even as circulation strikes! Set of 9 choice animal-themed coins, and a unique opportunity for the North African specialist 4. Australia - An original 1966 Proof Set of six coins, Penny to Silver 50 Cents, housed in Est $180-210 blue presentation case of issue with brilliant coinage, the Half Dollar evenly-toned. While the uncirculated sets of the same date are common, the Proof strikings remain very elusive (Krause value: $290) 5. Australia - 1969 Proof Set of 6 coins, Cent to 50 Cents (PS.31), lovely frosted strikings Est $125-140 in original plastic casing, the Five Cent slightly rotated (Cat. US $225) 6. -

H/W Or CP) TRS None None S and H/W Or CP) 48 None None None D Services Ltd

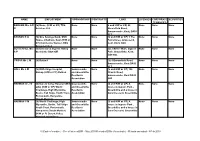

NAME EMPLOYMENT SPONSORSHIP CONTRACTS LAND LICENSES CORPORATE SECURITIES TENANCIES BARHAM Mrs A E (S) None, (H/W or CP) TRS None None S and H/W or CP) 48 None None None D Services Ltd. Broomfield Road, Swanscombe, Kent, DA10 0LT BASSON K G (S) One Savings Bank, OSB None None (S and H/W or CP) 1 The None None None House, Chatham, Kent.(H/W or Turnstones, Gravesend, CP) Call Centre Worker, RBS Kent, DA12 5QD Group Limited BUTTERFILL Mrs (S) Director at Ingress Abbey None None (S) 2 Meriel Walk, Ingress None None None S P Greenhthe DA9 9UR Park, Greenhithe, Kent, DA9 9GL CROSS Ms L M (S) Retired None None (S) 4 Broomfield Road, None None None Swanscombe, Kent DA10 0LT HALL Ms L M (S) NHS Kings Hospital, Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) 156 None None None Sidcup (H/W or CP) Retired and Greenhithe Church Road, Residents Swanscombe, Kent DA10 Association 0HP HARMAN Dr J M (S) Darent Valley Hospital (Mid- Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) A None None None wife) (H/W or CP) World and Greenhithe house in Ingress Park , Challenge, High Wycombe, Residents Greenhithe and a house in Bucks. Tall Ships Youth Trust, Association Sara Crescent, Greenhithe Portsmouth, Hampshire (Youth Mentor) HARMAN P M (S) World Challenge, High Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) A None None None Wycombe, Bucks. Tall Ships and Greenhithe house in Ingress Park , Youth Trust, Portsmouth, Residents Greenhithe and a house in Hampshire (Youth Mentor) Association Sara Crescent, Greenhithe (H/W or P) Darent Valley Hospital (midwifery) V:\Code of conduct - Dec of Interest\DPI - May 2015\Record of DPIs (for website) - PHarris amended - 8 Feb 2018 HARRIS PC (S) Retired. -

KENT. 1027 Brightman Waiter, 11 Woodall Terrace, Canty J

SHC) TRADES DIRECTORY.] KENT. 1027 Brightman WaIter, 11 Woodall terrace, Canty J. T. 150 St. Albans rd. Dartford Cloke .l\Irs.:.Sarah, Boughton Moncilelsea, Queenborollgh, Sheerness Caple Arthur, 16 Brook street, Northum- Maidstone . Brightwell H. Erith rd. Bexley Heath S.O berland Heath, Belvedere Coates !Irs. Anna. Mana, 57 James street, Brisley Mrs. Amelia, Stone, Dartford Card Chas. 49 Saxton st. New Brompton Sheemess-on-Sea. .. Brislev W. C. Park ter. Greenhithe S.O Card Frederick, Seal, Sevenoaks Cockell Mrs. Jane ElIen, 3 HIgh st. Milton. Brist~w H. C. 85 Rochester av. Rochester Carden W. 4 Harbour street, Whitstable Sittingboume Bristow Mrs. M. A. Hildenboro', Tonbridge Carey Frederick, Westwell, Ashford Cockram Mrs. A. 1 King Edward rd.Chthm Bristow Mrs. Sarah, Boughton Monchel- Carlton A. W. Low. Halstow, Sittingbrn Cocks Albert, 3fj Scott street, Maidstone sea, Maidstone Carpenter Arth. G. 22 Carey st. Maidstone Coo J. T. 24 Havelock terrace, Faversham Brittain .J. 49 High st. Milton, Sittngbrn Carpenter John, 23 Hadlow rd. Tonbridge Cole Charles, 9 Prospect row, Chatham Britter W. 1 Upper Stone street, Maidstn Carrano Gretano, 83 Overy st. Dartford Cole J. Chiddingstone, Couseway,Tonbrdg Britton W. 89 Murston rd. Sittingbourne Carte!' Miss E. 2 Shirley rd, Sidcup R.S.O ICole Wm. 73 Nelson rd. Tunbridge Wells Broad Miss A. Isle of Graine, Rochester Carter Miss Hannah, 55 Whitstable Coleman & Son, Chart hill, Sutton,Maidstn Broad George, 11 Station road, Northfleet road, Canterbury Coleman A. H. 77 Bower street, Maidstone Broad H. A. Hoo St. Werburgh, Rochester Carter N. 61 Magpie Hall rd. Chatham Coleman E. -

Statutory Staffing Information Travel Plans to and from Chatham Grammar

| Chatham Grammar Travel Plans to and from Chatham Grammar Statutory Traveling to CGSG Traveling from CGSG Staffing By car from A206 Greenwich Train times from Greenwich Train times from Faversham Train times from Gillingham Bus directions from CGSG From A206 Greenwich, merge onto to Gillingham Railway Station to Gillingham Railway Station to Greenwich Railway Station to Hempstead Valley Information Blackwall Tunnel Southern Approach/A102 06.57 Greenwich 07.39 Faversham 15.34 Gillingham (Kent) Shopping Centre via the slip road to A20/A2/Lewisham/ 07.00 Maze Hill 07.47 Sittingbourne 15.38 Chatham Executive Principal – UKAT Bexleyheath Bus 132 from Gillingham St Augustines 07.02 Westcombe Park 07.52 Newington 15.42 Rochester Judy Rider BA (Hons) MA Follow A2/M2 Church at 15:20 07.05 Charlton 07.57 Rainham (Kent) 15.45 Strood (Kent) Exit onto A289 towards Gillingham Arrives Hempstead Valley Shopping Cenre, Principal – Chatham Grammar 07.10 Woolwich Arsenal 08.01 Gillingham 15.50 Higham Follow signs for Medway Tunnel and Stand Stop A at approximately 15:59 Wendy Walters BA (Hons) MA 07.13 Plumstead 15.59 Gravesend take the first and only slip road out of 07.16 Abbey Wood Bus directions from 16.02 Northfleet UKAT Trustee the tunnel to roundabout ahead. Keep Bus directions from CGSG in left-hand lane of slip road. 07.22 Slade Green Gravesend to CGSG 16.04 Swanscombe David Nightingale 07.30 Dartford 16.08 Greenhithe for Bluewater to Rainham At the roundabout, take the 3rd exit Bus 190 from Gravesend Railway Station, Governing Body 07.34 Stone -

Christmas and New Year 2020/21 Bank Holiday Pharmacy Opening Hours: Ashford

Christmas and New Year 2020/21 Bank Holiday Pharmacy Opening Hours: Ashford The pharmacies listed below should be open as shown. The details are correct at the time of publishing but are subject to change. You are advised to contact the pharmacy before attending to ensure they are open and have the medication you require. Details of local pharmacies can also be found by scanning the code opposite or by visiting www.nhs.uk Monday Christmas Day New Years Day Town Pharmacy Name Address Phone Number 28th Dec 2020 25th Dec 2020 1st Jan 2021 Bank Holiday Ashford Asda Pharmacy Kimberley Way, Ashford, Kent, TN24 0SE 01233 655010 Closed 09:00-18:00 10:00-17:00 Unit 4, Barrey Road, Ashford Retail Park, Ashford Boots the Chemists 01233 503670 Closed 09:00-18:00 09:00-18:00 Sevington, Ashford, Kent, TN24 0SG Ashford Boots the Chemists 56 High Street, Ashford, Kent, TN24 8TB 01233 625528 Closed Closed 10:00-16:00 Unit 3 Eureka Place, Trinity Road, Eureka Ashford Delmergate Ltd 01233 638961 14:00-17:00 Closed Closed Business Park, Ashford, Kent, TN25 4BY Ashford Kamsons Pharmacy 92 High Street, Ashford, Kent, TN24 8SE 01233 620593 09:00-12:00 Closed Closed Lloydspharmacy (in Simone Weil Avenue, Bybrook, Ashford, Kent, Ashford 01233 664607 Closed 10:00-16:00 10:00-16:00 Sainsbury) TN24 8YN Tenterden Boots the Chemists 1-2 High Street, Tenterden, Kent, TN30 6AH 01580 763239 10:00-13:00 10:00-16:00 10:00-16:00 Christmas and New Year 2020/21 Bank Holiday Pharmacy Opening Hours: Canterbury & Coastal The pharmacies listed below should be open as shown. -

The Sovereign Grant and Sovereign Grant Reserve Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18

SOVEREIGN GRANT ACT 2011 The Sovereign Grant and Sovereign Grant Reserve Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 and Section 4 of the Sovereign Grant Act 2011 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 27 June 2018 HC 1153 © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us using the contact details available at www.royal.uk ISBN 978-1-5286-0459-8 CCS 0518725758 06/18 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Produced by Impress Print Services Limited. FRONT COVER: Queen Elizabeth II and The Duke of Edinburgh visit Stirling Castle on 5th July 2017. Photograph provided courtesy of Jane Barlow/Press Association. CONTENTS Page The Sovereign Grant 2 The Official Duties of The Queen 3 Performance Report 9 Accountability Report: Governance Statement 27 Remuneration and Staff Report 40 Statement of the Keeper of the Privy Purse’s Financial Responsibilities 44 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General to the Houses of 46 Parliament and the Royal -

The Chapels Royal of Britain. Iv

THE CHAPELS ROYAL OF BRITAIN THE CHAPELS ROYAL OF BRITAIN. IV. CHAPEL ROYAL, WHITEHALL. BY J. CRESSWELL RoscAMP, M.E. "Sir, you Must no more call it York Place: that is past,. For since the Cardinal fell, that title's lost ; 'Tis now the King's, and call'd-Whitehall." HITEHALL derived its name from the old Palace that stood W there till it was destroyed by fire in 1698. At the present time it is principally known from being the headquarters of aU the various offices connected with the Government and for the Horse Guard's building which was designed by Kent and is beautifully proportionate. The Palace of Whitehall was original! y known as " York House,'"~ and was the London residence of the Archbishops of York till •~ it was delivered and demised to the King (Henry VIII) by Charter February 7 (1529), on the disgrace of Cardinal Wolsey, Arch bishop of York, and was t,hen called Whitehall." It was built in 1240 by Hubert, Earl of Kent, and soon afterwards became the property of the Friars Predicant of Black Friars (Dominicans). who in 1248 sold it to Walter de Grey, Archbishop of York; and from that time to the fall of Wolsey it belonged to the See of York. Cll:rdinal Wolsey built much on to it including a Chapel, and it assumed under his ambitious tenure a splendour equal to, if not. surpassing, that of any Royal residence. The Cardinal had a passion for architecture and building, and loved pomp and magnificence, and thus it is not surprising to find his having made great additions, as he did at Oxford and Hampton Court. -

DARTFORD U S I L S F N R O L a Bus Stop E I a L D R H L S E R E T R C E C T S LE E OAKES L U O V T E P O N T

EXPLOREKENT.ORG C E N T BROWNING ROAD T R N A E C L S R E O R A C D D A L O L W R E D E N V Signed on-road cycle route A A L A C L H O C M E E L R N O D L E A E I S D M PLACES OF INTEREST O A P E E S R E Y R N G E S R O A O Surfaced – Traffic-free, Bridleways, E K R V Temple Hill N B TREVELYAN CL E C R D N T E L R T R Restricted Byways and Byways Open to All Traffic U O E E S N IV E S V O LA SH E E I E T N RI H E DAN CRT IC E AD K R GROVE PERRY L RO ROAD D G FARNO DICKENS AVENUE WSON River Darent R E AD Pedestrianised roads LA IV C RO The Orchard Theatre A ES DUNKIN ROAD 1 E Y KEY 2 O 0 J 2 F 6 C A R ST UNDS ROAD EDM R E E N Footpath K O M L IL R L O W A Central Park Gardens D 2 A Y Promoted walking route * P R I E O S15 T E BURNHAM ROAD R S O N Y Darent Valley S L N AY R CREEK MILL WAY W C N * For more information vistit explorekent.org M DE E Y O SI D ER D S A A Path V R Y R RI RNE A O D OU G Y F N ERB HILLTOP A N 3 Brooklands Lake A H Y S E W IR R R W N O O R UMBER RO N A N O H AD E L A A School A AVONMOUTH ROAD K D M D D N SAVOY ROAD O K 1 S14 OO WAY M R Named and numbered E H RSID EB VE C L RI I TT R I KINGSLEY AVENUE D L Darenth Country Park A PERRIN ROAD 4 O T R N CIS Industrial Place of interest AN E E R C Industrial F V S Estate DALE ST I E Named and numbered R R G T R Estate D T O C E N SV N SQUAR CE S ENO TEMPLE HILL RES H R E Y C G R E Beacon Wood Country Park C U 5 B V DARTFORD U S I L S F N R O L A Bus stop I A L E D R H L S E R E T R C E C T S LE E OAKES L U O V T E P O N T B I A L R N A M E 2 C G T E C V 02 C T L A S P 6 O E RI D O S R O R Hospital RY N E R S I D C G Located on the border of Kent, London and L T R OS H A E E V S E I T L R N Bluewater Shopping Centre C 6 L Y O T A S O A N P H V R M I R IA M E I K O RO N S R ANNE OF CLEVES ROAD AD U U Y R Railway with station E Essex, Dartford is one of the most exciting and G PRIORY ROAD R IVE C R HAL D E D LF E ORD W N TLE AY N T S A Dartford Borough Museum / WILLIAM MUNDY WAY T AY R W FOSTER DRIVE R A O K AN Toucan crossing 7 L N M dynamic towns in the county. -

Tudor Coinage B.J

TUDOR COINAGE B.J. COOK Introduction THE study of Tudor coinage since the foundation of the British Numismatic Society has been overwhelmingly dominated by two figures, Henry Symonds (PI. 3c) in the first half of the 20th century, and Christopher Challis (PI. 7b) from the 1970s to the present day. It is pleasingly apposite that Symonds's contribution is considered in detail elsewhere in this volume by Christopher Challis. The work of both Symonds and Challis has not for the most part been numismatic in the very technical sense: neither of them has produced catalogues, or works of detailed classification. Their achievement has been rather to provide an unparalleled insight into the production, organisation and use of coinage, that scholars of other periods can only hope to emulate, rather than excel. Specialist work on the coinage of the Tudors before the foundation of the Society was in fact sparse in the extreme. In Brooke's English Coins of 1933 the only such early contribution deemed worthy of inclusion in the bibliography was Sir John Evans' 1886 paper on the debased coinage of Henry VIII, published in the Numismatic Chronicle.' Occasionally picked up by modern scholars is A.E. Peake's 1891 article 'Some notes on the coins of Henry VII', which was an enterprising attempt to link details of the coinage with historical events, not all of which may have been wholly misguided.2 Given this scope for further investigation, it cannot be said that the foundation of the BNS did a great deal initially to remedy this apparent neglect, since work on Tudor numis- matics in the first half of the 20th century continued to be somewhat restricted, apart, of course, from Henry Symonds (the most spectacular exception to this generalisation), who split his many publications between the Journal and the Numismatic Chronicle. -

N THEREINACHC0.,Lnc

tecf 6y^ IsS Zs^V^ v v V V N Embroidery design for butterflies for use lines in on wo ist.B, lingerie, children's etc. the butterflies should clothes, ATI the METHOD OF TRANSFERRING. bo outlined, or if n handsomer single with French stem or development is desired cover tlie lines D^solve a half of whipping stitch. On lingerie materials the dots in teaspoonful washing powder or a small piece of soap in tv/o-thirda of a glass of Ijc&vorked in the wings of the butterflies could "crater. To this a eyelet. If the butterflies axe embroidered in add tablespoonful of ammonia. Place the material on which the transfer is to be made SET*iuimJ should colors, shades that liunnonizp on a Uo wed. xyifch the biie^ hard, onrooth surface, Saturate the back of the design with the al>ove solution, pla^e the design f«co down on the material, laying a stieet of thick paper over the back of the hold with one and design; ?irm'.y &and with the bowl of a Bpoca pib, with pressure, fronl vou. By following these diregions barefulljf some years ago in Paris, and appears' in one when it suits her and Iier cos- place. Th* two tutne. Yeomen of the Guard Incidentally, she :;iys tl.e < .1- JOIN lift the brass platter from the table ored is to IN wis be regarded merely a.- OBSERVANCE ami inarch to the head the a of lino of matter of decoration, rather than a artitlcial women. They are followed by the hair. -

Proctor Ebbsfleet & Matthews Built Form Character Study Architects

Proctor Ebbsfleet & Matthews Built Form Character Study Architects Progress Mtg 01 - 23.02.18 1 Scope of the Report: areas of influence Key Key opportunity to influence Limited opportunity to influence No opportunity to influence SWANSCOMBE PENINSULA Croxton Garry Craylands Lane NORTHFLEET RIVERSIDE Northfleet West Station Quarter Northfleet North East EBBSFLEET CENTRAL Northfleet Rise EASTERN QUARRY Castle Hill East Western Cross Alkerden Castle Hill Central Station Quarter South Ebbsfleet Green Castle Hill South Springhead 2 Aerial view: with red line of proposed new neighbourhoods SWANSCOMBE PENINSULA Greenhithe Croxton Garry Craylands Lane NORTHFLEET RIVERSIDE Swanscombe Northfleet West Station Quarter Northfleet North East EBBSFLEET CENTRAL Gravesend Northfleet Rise EASTERN QUARRY Castle Hill East Western Cross Alkerden Castle Hill Central Station Quarter South Ebbsfleet Green Castle Hill South Springhead 3 Nolli Plan: current urban form & public realm 4 Key Narrative: Topography PLACE NAMES & THE LANDSCAPE PALIMPSEST GEOLOGY LANDSCAPE FEATURES TO BE CONSIDERED IN THE DESIGN RIVER TO MARSH TO CHALK ESCARPMENTS 5 Key Narrative Topography: place names & the landscape palimpsest The River Thames and its estuary has throughout history been a vital corridor for trade, travel and industry. This landscape now contains a complex ‘palimpsest’ of features dating from the prehistoric periods through to the modern day. The present landscape is a mosaic of dense urban development, commerce and industry, interspersed with tracts of rural countryside and marshland. The present aspect of the lower Thames Valley is very different from what it was a thousand years ago. Instead of being confined within the regular banks, the river must have spread its sluggish waters over a broad lagoon, which was dotted with marshy islands. -

September 2014

You will note the addition to names after praying for the community of other churches, these are the names of St Mary Greenhithe the Ministers or those who lead the church there. Please include them in your prayers. Please pray for the following omissions: Monday morning - prayer for all those on the wards at the Darent Valley hospital – Carol visits wards from 9 till 12 each Monday after Morning Prayer at 8am in the chapel. Sunday 14th Sept - Carol will be taking communion to the bedsides of people in the Darent Valley Hospital (She will be doing this every 2nd and 5th Sunday each month). Carol and Andrew both chaplain on different day’s and time’s at Asda during the week. Remember them in prayer throughout the week. September Prayer Diary 2014 September is friendship month. Monday 1St September Please pray for peace for Naomi’s Mother Christine Munns as she mourns the loss of her best friend Pauline. Ask God to draw close to all of What a friend we have in JESUS! Pauline’s friends and family during this difficult time. Pray for the Arkell family now they have sadly left us for pastures new. What a friend we have in Jesus, Let us give thanks and praise to God for their time here at St Mary. Over All our sins and grief to bear! the years they have been good friends to many of us and shared so much What a privilege to carry of our ups and downs. Let us remember to continue in our prayers for Everything to God in prayer! them over the coming months as they adapt to huge changes in their lives O what peace we often forfeit and settle into a new home, schools, jobs and community.