The Raising of Charles Edward's Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day 1 Trail Safety Trail Overview Key Contacts

The Great Glen Canoe Trail Is one of the UK’s great canoe adventures. You are advised to paddle the Trail between It requires skill, strength, determination Banavie and Muirtown as the sea access and above all, wisdom on the water. sections at each end involve long and difficult portage. Complete the Trail and join the select paddling few who have enjoyed this truly Enjoy, stay safe and leave no trace. unique wilderness adventure. www.greatglencanoetrail.info Designed and produced by Heehaw Digital | Map Version 3 | Copyright British Waterways Scotland 2011 Trail Safety Contacts Key When planning your trail: When on open water remember: VHF Operation Channels Informal Portage Route Ensure you have the latest Emergency Channel – CH16 Camping Remember to register your paddle trip Orientation weather forecast Read the safety information provided Scottish Canals – CH74 Commercial Panel Wear appropriate clothing Camping by the Caledonian Canal Team Access/Egress Plan where you are staying and book Choose a shore and stick to it Point Handy Phone Numbers Canoe Rack appropriate accommodation if required Stay as a group and look out for Lock Gates each other Canal Office, Inverness – 01463 725500 Bunk House Canal Office, Corpach - 01397 772249 Swing Bridges Be prepared to take shelter should Shopping On the canal remember: the weather change Inverness Harbour - 01463 715715 A Road Parking Look out for and use the Canoe Trail pontoons In the event of an emergency on the water, Met Office – 01392 885680 B Road call 999 and ask for the coastguard Paddle on the right hand side and do not HM Coast Guard, Aberdeen – 01224 592334 Drop Off/Pick Up Railway canoe sail Police, Fort William – 01397 702361 Toilets Great Glen Way Give way to other traffic Always wear a personal Police, Inverness – 01463 715555 Trailblazer Rest River Flow Be alert, and be visible to approaching craft buoyancy aid when on Citylink – 0871 2663333 Watch out for wake caused by larger boats the canal or open water. -

Pericles Coastal Interpretation

PERICLES Title Text Coastal Interpretation Webinar Myles Farnbank Head of Guides & Training for Wilderness Scotland Scotland Manager for Wilderness Foundation UK Vice-chair Scottish Adventure Activities Forum (SAAF) 30 years experience as an international wilderness guide - Mountain, sailing, sea kayaking, canoeing and wildlife guiding Created UK’s first Guide Training Programme in 2009 Active guide trainer throughout UK & internationally Lecturer Adventure Tourism, Marine & Coastal Tourism & Ecotourism Sit on Cross-party Working Group Recreational Boating & Marine Tourism - Scottish Parliament Introductions If everyone could introduce themselves and give a brief reason for attending todays webinar What is Scottish Coastal Cultural History? In break out groups - 15 minutes to note down anything that you feel is part of coastal Scotland’s cultural history story. You don’t have to agree - go ‘high low and wide’ Please agree someone in the group to scribe and feedback on the things you noted down Overview - morning session Context - Marine & Coastal Tourism What is Interpretation? Archaeology and brief history of the area Boundary or Bridge - psycho-geography of the coast Coastal Castles Coastal food & Net Product Whaling and seals Commerce and Culture Lost at Sea Lighting the way We are going to take a very wide view of coastal cultural history which will touch on most of the things you have shared. Overview - afternoon session Mystic Places - Folklore Coastal creations - art, music, poetry and prose Crofters and Fisherfolk - Personal stories from Mallaig & Arisaig We are going to take a very wide view of coastal cultural history which will touch on most of the things you have shared. -

Scotland's Road of Romance by Augustus Muir

SCOTLAND‟S ROAD OF ROMANCE TRAVELS IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF PRINCE CHARLIE by AUGUSTUS MUIR WITH 8 ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street W,C, Contents Figure 1 - Doune Castle and the River Tieth ................................................................................ 3 Chapter I. The Beach at Borrodale ................................................................................................. 4 Figure 2 - Borrodale in Arisaig .................................................................................................... 8 Chapter II. Into Moidart ............................................................................................................... 15 Chapter III. The Cave by the Lochside ......................................................................................... 31 Chapter IV. The Road to Dalilea .................................................................................................. 40 Chapter V. By the Shore of Loch Shiel ........................................................................................ 53 Chapter VI. On The Isle of Shona ................................................................................................ 61 Figure 3 - Loch Moidart and Castle Tirrim ................................................................................. 63 Chapter VII. Glenfinnan .............................................................................................................. 68 Figure 4 - Glenfinnan .............................................................................................................. -

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for February 19Th, 2016

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for February 19th, 2016 To see what we've added to the Electric Scotland site view our What's New page at: http://www.electricscotland.com/whatsnew.htm To see what we've added to the Electric Canadian site view our What's New page at: http://www.electriccanadian.com/whatsnew.htm For the latest news from Scotland see our ScotNews feed at: http://www.electricscotland.com/ Electric Scotland News Is archaeology in Scotland interesting? Yes! Welcome 2016 with a new purpose! Advance into a community of learners actively pursuing the progress of archaeology in Scotland. Scot Scholars is an armchair tour of Scotland’s geography, geology, OS maps, and up-to-the-minute archaeological methods, specifically designed for North Americans. View more than a hundred authentic images as you listen to the course. The Scot Scholars presentation is almost two hours in length. An outline summary follows each of the six units, so note-taking is not expected. There are no quizzes or tests. The pace is unpressured, but the content is compressed—short viewing sessions are best for most people. Surprise yourself with how much you will learn. You will find the Scot Scholars course at ScotScholars.com on the internet. Join us today! at: http://scotscholars.com/ The above is an advert but I have to say that it's one that is most interesting in my opinion. I have always enjoyed programs like Time Team but have to say that some of what they do is a touch beyond me as some of their technical work is not explained as well as it might be. -

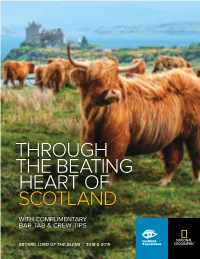

Through the Beating Heart of Scotland with Complimentary Bar Tab & Crew Tips

THROUGH THE BEATING HEART OF SCOTLAND WITH COMPLIMENTARY BAR TAB & CREW TIPS TM ABOARD LORD OF THE GLENS | 2018 & 2019 TM Lindblad Expeditions and National Geographic have joined forces to further inspire the world through expedition travel. Our collaboration in exploration, research, technology and conservation will provide extraordinary travel expe- riences and disseminate geographic knowledge around the globe. DEAR TRAVELER, The first time I boarded the 48-guest Lord of the Glens—the stately ship we’ve been sailing through Scotland since 2003—I was stunned. Frankly, I’d never been aboard a more welcoming and intimate ship that felt somehow to be a cross between a yacht and a private home. She’s extremely comfortable, with teak decks, polished wood interiors, fine contemporary regional cuisine, and exceptional personal service. And she is unique—able to traverse the Caledonian Canal, which connects the North Sea to the Atlantic Ocean via a passageway of lochs and canals, and also sail to the great islands of the Inner Hebrides. This allows us to offer something few others can—an in-depth, nine-day journey through the heart of Scotland, one that encompasses the soul of its highlands and islands. You’ll take in Loch Ness and other Scottish lakes, the storied battlefield of Culloden where Bonnie Prince Charlie’s uprising came to a disastrous end, and beautiful Glenfinnan. You’ll pass through the intricate series of locks known as Neptune’s Staircase, explore the historic Isle of Iona, and the isles of Mull, Eigg, and Skye, and see the 4,000-year-old burial chambers and standing stones of Clava Cairns. -

High Mingarry (Mingaraigh Ard), Moidart, Invernesss-Shire (NM 68827 70315)

High Mingarry (Mingaraigh Ard), Moidart, Invernesss-shire (NM 68827 70315) A survey undertaken by the Moidart History Group, Comann Eachdraidh Mùideart, in Spring / Summer 2008 Historical background and notes High Mingarry (Mingearaidh Ard), Moidart High Mingarry viewed from the north. Bracken covers most areas of past cultivation. High Mingarry, Moidart. (NM 68800.70200) In historic records, the township of Mingarry appears as Mengary, Mingary and Mingarry. The original settlement was likely to have been sited to the north of the parliamentary road, at the place now known as High Mingarry where scattered ruins are evident. Aaron Arrowsmith's Map of Scotland 1807, shows that Mingarry was some distance to the north of the proposed Parliamentary road and that a track left the route of the road to the west of the Mingarry Burn and climbed the hill in a north-easterly direction to the settlement. The track then continued over the hill to the south shore of Loch Moidart to meet the route of the road near the River Moidart crossing point at the east end of the loch. The Lochshiel Estate Map, probably drawn up about 1811-1816 indicates that at that time the settlement of Mingarry was sited on the hillside to the north of Loch Shiel and to the north of the parliamentary road, mainly between two tributaries of the Mingarry Burn. At that time, there were no buildings near the road. Historic Background Pre 1745 The date of origin of the township is unknown. Moidart was part of the mainland Clanranald Estates. The settlement appears in lists of Estate rentals 1691-1771 as Mengary. -

West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Plana Leasachaidh Ionadail Na Gàidhealtachd an Iar Agus Nan Eilean

West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Plana Leasachaidh Ionadail na Gàidhealtachd an Iar agus nan Eilean Adopted Plan September 2019 www.highland.gov.uk How to Find Out More | Mar a Gheibhear Tuilleadh Fiosrachaidh How to Find Out More This document is about future development in the West Highland and Islands area, including a vision and spatial strategy, and identified development sites and priorities for the main settlements. If you cannot access the online version please contact the Development Plans Team via [email protected] or 01349 886608 and we will advise on an alternative method for you to read the Plan. (1) Further information is available via the Council's website . What is the Plan? The West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan (abbreviated to WestPlan) is the third of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, forms "the development plan" that guides future development in the Highlands. WestPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the West Highland and Islands area over the next 20 years. In preparing this Plan, The Highland Council have held various consultations firstly with a "Call for Sites" followed by a Main Issues Report then an Additional Sites Consultation followed by a Proposed Plan. The comments submitted during these stages have helped us finalise this Plan. This is the Adopted Plan and is now part of the statutory "development plan" for this area. 1 http://highland.gov.uk/whildp Adopted WestPlan The Highland Council 1 How to Find Out More | Mar a Gheibhear Tuilleadh Fiosrachaidh What is its Status? This Plan is an important material consideration in the determination of planning applications. -

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series: Fort William Produced from Information Contained Within The Gazetteer for Scotland. Tourist Guide of Fort William Index of Pages Introduction to the settlement of Fort William p.3 Features of interest in Fort William and the surrounding areas p.5 Tourist attractions in Fort William and the surrounding areas p.9 Towns near Fort William p.11 Famous people related to Fort William p.14 This tourist guide is produced from The Gazetteer for Scotland http://www.scottish-places.info It contains information centred on the settlement of Fort William, including tourist attractions, features of interest, historical events and famous people associated with the settlement. Reproduction of this content is strictly prohibited without the consent of the authors ©The Editors of The Gazetteer for Scotland, 2011. Maps contain Ordnance Survey data provided by EDINA ©Crown Copyright and Database Right, 2011. Introduction to the city of Fort William 3 Located 105 miles (169 km) north of Glasgow and 145 miles (233 km) from Edinburgh, Fort William lies at the heart of Lochaber district within the Highland Council Settlement Information Area. The first fort was built at the mouth of the River Lochy in 1645 by General George Monk (1608-70) who named it Inverlochy, whilst the adjacent village which Settlement Type: small town became established due to the trade associated with the herring trade was named Gordonsburgh. In 1690 the Population: 9908 (2001) fort was enlarged and was renamed Fort William, whilst Tourist Rating: the village underwent several name changes from Gordonsburgh to Maryburgh, Duncansburgh, and finally National Grid: NN 108 742 by the 19th Century it took the name of Fort William, although remains known as An Gearasdan Fort William Latitude: 56.82°N Ionbhar-lochaidh - the Garrison of Inverlochy - in Gaelic. -

Download Brochure (PDF)

SCOTLAND HIGHLANDS & ISLANDS THROUGH THE HEART OF THE COUNTRY VIA THE CALEDONIAN CANAL WITH COMPLIMENTARY BAR TAB & CREW TIPS 2020 & 2021 VOYAGES | EXPEDITIONS.COM DEAR TRAVELER, The first time I boarded the 48-guest Lord of the Glens—the stately ship we’ve been sailing through Scotland since 2003—I was stunned. Frankly, I’d never been aboard a more welcoming and intimate ship that felt somehow to be a cross between a yacht and a private home. She’s extremely comfortable, with teak decks, polished wood interiors, fine contemporary regional cuisine, and exceptional personal service. And she is unique—able to traverse the Caledonian Canal, which connects the North Sea to the Atlantic Ocean via a passageway of lochs and canals, and also sail to the great islands of the Inner Hebrides. This allows us to offer something few others can—an in-depth journey through the heart of Scotland, one that encompasses the soul of its highlands and islands. You’ll take in Loch Ness and other Scottish lakes, the storied battlefield of Culloden where Bonnie Prince Charlie’s uprising came to a disastrous end, and beautiful Glenfinnan. You’ll pass through the intricate series of locks known as Neptune’s Staircase, explore the historic Isle of Iona, and the isles of Mull, Eigg, and Skye, and see the 4,000-year-old burial chambers and standing stones of Clava Cairns. There’s even time for a visit to the most remote pub in the British Isles. Scotland is a land of grand castles, beautiful moorlands, sacred abbeys, and sweeping mountains and you’ll have the opportunity to experience it all as few get to. -

Platforms and a Lithic Scatter, Loch Doilean, Sunart, Lochaber by Clare Ellis (Argyll Archaeology) with Torben Bjarke Ballin and Susan Ramsay

ARO20: Activities in the woods: platforms and a lithic scatter, Loch Doilean, Sunart, Lochaber by Clare Ellis (Argyll Archaeology) with Torben Bjarke Ballin and Susan Ramsay Archaeology Reports Online, 52 Elderpark Workspace, 100 Elderpark Street, Glasgow, G51 3TR 0141 445 8800 | [email protected] | www.archaeologyreportsonline.com ARO20: Activities in the woods: platforms and a lithic scatter, Loch Doilean, Sunart, Lochaber Published by GUARD Archaeology Ltd, www.archaeologyreportsonline.com Editor Beverley Ballin Smith Design and desktop publishing Gillian McSwan Produced by GUARD Archaeology Ltd 2016. ISBN: 978-0-9928553-9-0 ISSN: 2052-4064 Requests for permission to reproduce material from an ARO report should be sent to the Editor of ARO, as well as to the author, illustrator, photographer or other copyright holder. Copyright in any of the ARO Reports series rests with GUARD Archaeology Ltd and the individual authors. The maps are reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. All rights reserved. GUARD Archaeology Licence number 100050699. The consent does not extend to copying for general distribution, advertising or promotional purposes, the creation of new collective works or resale. Contents Summary 6 Introduction and location 6 Archaeological background 6 Method of excavation 6 Raised terrace 6 Platforms 8 Results 8 Radiocarbon dates 8 Mesolithic 8 Late Iron Age? 10 Medieval platforms 10 Charcoal-burning platforms 17 Specialist reports 25 The lithic artefacts -

Tour Itinerary

GEEO ITINERARY SCOTLAND – Summer Day 1: Edinburgh Arrive at any time. Attend a welcome meeting in the evening. Arrive at any time. We recommend arriving a day early to fully explore this lively city. There are no planned activities until an evening welcome meeting. Check the notice boards or ask at reception for the exact time and location of the group meeting, typically 6:00 p.m. or 7:00 p.m. After the meeting, you might like to take the option of heading out for a meal in a nearby local restaurant to further get to know your tour leader and travel companions. Please make every effort to arrive on time for this welcome meeting. If you are delayed and will arrive late, please inform us. Your tour leader will then leave you a message at the front desk informing you of where and when to meet up. Day 2: Edinburgh/Inverness (B) Enjoy an orientation walk of Edinburgh ending in the heart of the city, Royal Mile road. Opt to visit Edinburgh Castle, or explore the city on your own. In the afternoon, hop on a private transfer to the Highlands. Enjoy an orientation walk of Edinburgh ending in the heart of the city, Royal Mile road. After the orientation walk, we highly recommend visiting Edinburgh Castle. This historic fortress dominates the skyline of the city from its position on Castle Rock. It is the home of the Crown Jewels of Scotland, the Stone of Destiny, and the National War Museum. The entrance fee of 20 GBP includes entrance to all attractions within Edinburgh Castle. -

125217081.23.Pdf

u, uiy. (Formerly AN DEO GREINE) 'dSfie Montdly Magazine of Jin (Somunn tfaiddealaefy Volume XLI. October, 1945, to September, 1946, inclusive. AN COMUNN GAIDHEAIvACH, 131 West Regent Street, Glasgow. -e-S CONTENTS. -8^ GAELIC DEPARTMENT. PAGE Am Fear Deasachaidh— D.D. airson ar Fear deasachaidh 84 Am B.B.C. agus a’ Ghaidhlig 47 Eadar sinn fhein, 45, 55, 05, 75, 84, An Riaii Orpine ...... 37 94, 115. An t-Urr, Calum MacLeoid 87 Facal san cjealachadh 66 Ar Duthaich agus ar Daoine 98 Facal san dol seachad, 2, 10, 18, 28, Biadh is Beoshlaint 37 38, 48, 58, 68, 78, 98, 109. Canain Bheo 27 Failte air an t-Saighdear 84 Comhfhurtachd agus cainnt 07 Leabhraichean 43 Cor na G&idhlig an diugh 107 Litir Comunn na h-Oigridh, 6, 13, 21 Gh&idhlig Bhretonach, A’ 17 31, 40, 50, 00, 70, 79^89, 99, 109. Latha Ghlinn Fhionghuin 1 Maoin Litreachas G&idhlig, 7, 10. 20, Rathaidean agus Uidheaman-giulain 9 36, 46, 56, 66, 95. Slighean nan Eilean 77 Oisinn na h-Oigridh 100, 110 Air a’ Chnoc 25, 34, 44, 54, 04 Seanchas 11 - Air an Duthaich 36 54 Sgeulachd bheag ... H2 An t-Ard Mharaiche Dearg 25 Sgeulachdan o’n Lochlannais 15 Bas Chairdean 7, 33, 30, 115 Sgiobaireachd 1' l Coinneach Odhar Fiosaiche ...... 114 Suiaire, An 112 Cothrom is Anacothrom 84 Bardachd. PAGE A’ Bbeinn 36 Gleann Comhann 15 Aile na Mara 0 lonndrainn Cuain 113 Alltan Beinn 74 lorriacheist 84 An Eala Aonranach 83 Leannan 43 An Gradh 90 Leig dhiot t’ lomagain 84 An Guth 04 MJiag mo Reusan - =.•- An t-Ailleagan 24 Miami an Fhogarraich do’n Eilean An t-Urr.