Scotland's Road of Romance by Augustus Muir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inner and Outer Hebrides Hiking Adventure

Dun Ara, Isle of Mull Inner and Outer Hebrides hiking adventure Visiting some great ancient and medieval sites This trip takes us along Scotland’s west coast from the Isle of 9 Mull in the south, along the western edge of highland Scotland Lewis to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles), 8 STORNOWAY sometimes along the mainland coast, but more often across beautiful and fascinating islands. This is the perfect opportunity Harris to explore all that the western Highlands and Islands of Scotland have to offer: prehistoric stone circles, burial cairns, and settlements, Gaelic culture; and remarkable wildlife—all 7 amidst dramatic land- and seascapes. Most of the tour will be off the well-beaten tourist trail through 6 some of Scotland’s most magnificent scenery. We will hike on seven islands. Sculpted by the sea, these islands have long and Skye varied coastlines, with high cliffs, sea lochs or fjords, sandy and rocky bays, caves and arches - always something new to draw 5 INVERNESSyou on around the next corner. Highlights • Tobermory, Mull; • Boat trip to and walks on the Isles of Staffa, with its basalt columns, MALLAIG and Iona with a visit to Iona Abbey; 4 • The sandy beaches on the Isle of Harris; • Boat trip and hike to Loch Coruisk on Skye; • Walk to the tidal island of Oronsay; 2 • Visit to the Standing Stones of Calanish on Lewis. 10 Staffa • Butt of Lewis hike. 3 Mull 2 1 Iona OBAN Kintyre Islay GLASGOW EDINBURGH 1. Glasgow - Isle of Mull 6. Talisker distillery, Oronsay, Iona Abbey 2. -

Mid - Argyll, Kintyre, Islay and Jura Home Care Service Housing Support Service

Mid - Argyll, Kintyre, Islay and Jura Home Care Service Housing Support Service Old Quay Head Campbeltown PA28 6ED Telephone: 01546 605500 Type of inspection: Announced (short notice) Completed on: 5 March 2020 Service provided by: Service provider number: Argyll and Bute Council SP2003003373 Service no: CS2004079966 Inspection report About the service Mid- Argyll, Kintyre, Islay and Jura Home Care Service is provided by Argyll and Bute Council and was registered by the Care Inspectorate in April 2011. The home care service offers personal, social, emotional and practical support to people experiencing care. Its aims are: - to provide a high quality care service that helps people remain in their own home - to provide practical support to relatives and friends caring for people in the community - to enable people to lead as independent a life as possible within their own community - to provide a service that takes account of people's preferences, wishes, personal circumstances, cultural and religious beliefs - to provide services in an anti-discriminatory way. At this inspection, we visited or spoke to people from all localities the service supported. What people told us During the time of our inspection the service supported 135 service users across all parts of the service. We spoke to 18 service users and family members and received 21 completed questionnaires. Most people were happy with their support. They felt the quality of staff and management was good and they received good information about the service. Where people felt there were more improvements to be made, we discussed their points with managers in a confidential way. -

I. the Parallel Roads of Lochaber Have Presented to Geologists a Problem, Which Is Still Unsolved

(595) XXVII.—On the Parallel Roads of Lochaber. By DAVID MILNE HOME, LL.D, (Plates XLL, XLIL, XLIII.) (Read 15th May 1876.) I. The Parallel Roads of Lochaber have presented to geologists a problem, which is still unsolved. Dr MACCULLOCH, about sixty years ago, when President of the Geological Society of London, first called attention to these peculiar markings on the Lochaber Hills, by an elaborate Memoir afterwards published in that Society's Transactions. He was followed by Sir THOMAS DICK LAUDER, who in the year 1824, read a paper in our own Society, illustrated by excellent sketches. His paper is in our Transactions. The next author who attempted a solution was the present Mr CHARLES DARWIN. He maintained that these Roads were sea-beaches, formed, when this part of Europe was rising from beneath the Ocean. He was followed by Professor AGASSIZ, Dr BUCKLANB, CHARLES BABBAGE, Sir JOHN LUBBOCK, ROBERT CHAMBERS, Professor ROGERS, Sir GEORGE M'KENZIE, Mr JAMIESON of Ellon, Professor NICOL, Mr BRYCE of Glasgow, Mr WATSON, and Mr JOLLY of Inverness. Sir CHARLES LYELL, though he wrote no special memoir, treated the subject pretty fully in his works, giving an opinion in support of the views of AGASSIZ. I took some little part myself in the discussion, having in the year 1847 read a paper in this Society, which was published in our Transactions. During the last five or six years, there has been an entire cessation of both investigation and discussion, in consequence probably of a desire to await the publication of more correct maps of the district, which at the request of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the Ordnance Survey Department undertook. -

The Scottish Isles – Island Hopping in the Hebrides (Spitsbergen)

THE SCOTTISH ISLES – ISLAND HOPPING IN THE HEBRIDES (SPITSBERGEN) This is a truly varied expedition cruise with many beach landings. Go on guided walks on remote islands and explore lonely beaches at your own pace, all the while immersing yourself in the wild beauty of the surroundings. Leaving Glasgow, our first island will be Arran, known as a microcosm of Scotland and a great contrast to the next – the wild, whisky island of Islay with its many distilleries. Voyaging west, the wildlife of the Treshnish Isles will be a splendid sight - bustling with seals, before the towering sea cliffs of the St. Kilda archipelago, teeming with nesting seabirds from puffins to predatory skuas, provide an unforgettable experience. We call at Stornoway to see the tough and unique Harris Tweed being woven, have a special pub visit in the bustling tiny port of Tobermory, capital of the Isle of Mull which also has an enticing range of craft shops and seafood. We walk the shores of one of ITINERARY Scotland’s most dramatic lochs, Loch Coruisk, surrounded by lofty mountains. We can hike island peaks for views stretching Day 1 ‘Dear Green Place’ over the seas, kayak in sheltered lochs, or simply stroll Our voyage starts in Glasgow. Meaning ‘Dear Green Place’ in Gaelic, Glasgow delightful gardens. These are all ‘ours’ for exploring. boasts over 90 parks and gardens. Famous for its Victorian as well as art nouveau architecture, it is home to such institutions as the Scottish Ballet, Opera and National Theatre. This is definitely a city you’ll want to explore more before you board MS Spitsbergen. -

Bishops, Priests, Monks and Their Patrons the Lords of the Isles and the Church

CHAPTER 5 Bishops, Priests, Monks and Their Patrons The Lords of the Isles and the Church Sarah Thomas Whilst the MacDonald contribution to the Church, and in particular to Iona, has been discussed, their involvement in the patronage of parish churches and secular clergy has up until now been neglected.1 This is an area of immense potential, given the surviving source material in the papal archives; through the study of clerical identities, building on the work of John Bannerman, we are able to identify connections between the clergy and the Lords of the Isles.2 The Lordship of the Isles incorporated two bishoprics, four monastic houses and approximately 64 parish churches of which the Lords had patronage of 41.3 In an age where the appropriation of parish churches to monastic and ecclesias- tical authorities was widespread, the Lordship’s patronage of so many parish churches meant that they had considerable influence over clerical careers and had significant scope to reward kindreds. However, that amount of control over ecclesiastical benefices might strain relations between lord and bishop. Relations with the monastic institutions were not always smooth either; a par- ticular issue was the admission of MacKinnons into the monastery of Iona. The Lordship lands lay within two dioceses; their lands in the Hebrides in the diocese of Sodor and their lands in Kintyre, Knapdale, Lochaber, Moidart, 1 Steer and Bannerman, Late Medieval Monumental Sculpture; Bannerman, ‘Lordship of the Isles’; M. MacGregor, ‘Church and Culture in the late medieval Highlands’ in J. Kirk (ed), The Church in the Highlands (Edinburgh, 1998); R.D. -

A History of the Lairds of Grant and Earls of Seafield

t5^ %• THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY GAROWNE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD. THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY A HISTORY OF THE LAIRDS OF GRANT AND EARLS OF SEAFIELD BY THE EARL OF CASSILLIS " seasamh gu damgean" Fnbemess THB NORTHERN COUNTIES NEWSPAPER AND PRINTING AND PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIMITED 1911 M csm nil TO CAROLINE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD, WHO HAS SO LONG AND SO ABLY RULED STRATHSPEY, AND WHO HAS SYMPATHISED SO MUCH IN THE PRODUCTION OP THIS HISTORY, THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE The material for " The Rulers of Strathspey" was originally collected by the Author for the article on Ogilvie-Grant, Earl of Seafield, in The Scots Peerage, edited by Sir James Balfour Paul, Lord Lyon King of Arms. A great deal of the information collected had to be omitted OAving to lack of space. It was thought desirable to publish it in book form, especially as the need of a Genealogical History of the Clan Grant had long been felt. It is true that a most valuable work, " The Chiefs of Grant," by Sir William Fraser, LL.D., was privately printed in 1883, on too large a scale, however, to be readily accessible. The impression, moreover, was limited to 150 copies. This book is therefore published at a moderate price, so that it may be within reach of all the members of the Clan Grant, and of all who are interested in the records of a race which has left its mark on Scottish history and the history of the Highlands. The Chiefs of the Clan, the Lairds of Grant, who succeeded to the Earldom of Seafield and to the extensive lands of the Ogilvies, Earls of Findlater and Seafield, form the main subject of this work. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Item Report PLS No 078/18

Agenda 6.1 Item Report PLS No 078/18 HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: South Planning Applications Committee Date: 23 October 2018 Report Title: 18/01564/S36: Coire Glas Pumped Storage Ltd. At Coire Glas, North Laggan. Report By: Area Planning Manager – South Purpose/Executive Summary Description: Revised Coire Glas Pumped Storage Scheme. Ward: 11 - Caol and Mallaig. Pre –Determination hearing : No Pre meeting Site Visit : Yes (19 Oct 2018) Reason referred to Council : Section 36 application and Community Council Objection All relevant matters have been taken into account when appraising this application. It is considered that the proposal accords with the principles and policies contained within the Development Plan and is acceptable in terms of all other applicable material considerations. Recommendation Members are asked to agree the recommendation to Raise No Objection to the application as set out in Section 12 of the report. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The proposal is a “national development” but not one advanced under Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997. The application requires determination by Scottish Ministers under Section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989. However, if approved, Scottish Ministers will issue a Direction under Section 57(2) of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 that deemed planning permission be granted for the development. 1.2 Consent for abstraction, diversion and use of water for generating electricity is also being sought under Section 10(5) and Schedule 5 of the Electricity Act 1989. This requires licences from Scottish Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA) under the Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2006 (CAR). 1.3 The Council at this stage is a consultee on the proposed development. -

Generating Benefits in the Great Glen Sse Renewables’ Socio-Economic Contribution Generating Benefits in the Great Glen

GENERATING BENEFITS IN THE GREAT GLEN SSE RENEWABLES’ SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION GENERATING BENEFITS IN THE GREAT GLEN ABOUT SSE RENEWABLES FOREWORD SSE Renewables is a leading developer and operator of renewable Over the years, the purpose of SSE Renewables has gone unchanged – to provide energy, with a portfolio of around 4GW of onshore wind, offshore people with the energy they need – but the world around us is moving quickly. With wind and hydro. Part of the FTSE-listed SSE plc, its strategy is to only 30 years to reach Net Zero carbon targets set by governments in the UK and drive the transition to a zero-carbon future through the world around the world, we believe concerted action against climate change is necessary. class development, construction and operation of renewable energy assets. In response, we have redoubled our efforts to create a low carbon world today and work towards a better world of energy tomorrow. We’ve set a goal to treble our SSE Renewables owns nearly 2GW of onshore wind capacity renewable output to 30TWh a year by 2030, which will lower the carbon footprint of with over 1GW under development. Its 1,459MW hydro portfolio electricity production across the UK and Ireland. Potential future projects in the Great includes 300MW of pumped storage and 750MW of flexible hydro. Glen can make significant contributions towards this goal. Its offshore wind portfolio consists of 580MW across three offshore sites, two of which it operates on behalf of its joint venture partners. For SSE Renewables, building more renewable energy projects in the Great Glen is SSE Renewables has the largest offshore wind development about more than just the environment. -

Lochaber Hydropower Scheme Consultancy Services for Rehabilitation of Scheme Infrastructure

05_ENERGY Lochaber Hydropower Scheme Consultancy Services for Rehabilitation of Scheme Infrastructure Spilling of Laggan Dam | Photo: Multiconsult The Lochaber Hydropower Scheme was first commissioned in 1929 and expanded in two subsequent stages to provide an original installed capacity of 75 MW and an annual energy production of some 460 GWh. The scheme comprises three principal reservoirs in cascade – Spey reservoir at the upstream end, Loch Laggan and reservoir and Loch Treig. No major rehabilitation works had been undertaken of the scheme until in 2009 replanting of the power station was commenced, being completed in November 2011 providing the scheme with a new installed capacity of 90 MW and annual energy production in excess of 600 GWh. The scheme’s main tunnel has not been dewatered for 35 years due to the reliance of the adjacent aluminium smelter upon the power produced by the scheme. Multiconsult is undertaking a strategic review to assess the next stages of rehabilitation and timing of the shutdwon of the scheme. PROJECT PROJECT TYPE LOCATION CLIENT TIME PERIOD KEY NUMBERS Lochaber Hydropo- Rehabilitation of Fort William, Scotland Rio Tinto Alcan 2015 to ongoing Capacity: 5 x 18 MW | Energy wer Scheme Strategic Hydropower Project Production: 600 GWh per annum Review | Storage Capacity: 269 million cubic metres | Francis Turbines, Turbine Design Head: 214 metres SCOPE OF WORK OUR SERVICES Assistance in the strategic planning of shut- • Assembling of historical records of down of the scheme to facilitate rehabilitation the main -

Fort Augustus Daytrip Routecard

FORT AUGUSTUS (22 MILES, 35 KM) RETURN ROUTE A scenic journey down the Great Glen along the Caledonian Canal DETAILS g Glendoe 0 1 2 3 4Kilometres Fort Augustus Lodge 62 B8 LEVEL Intermediate 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 Miles h c 2 A Caledonian Canal Glendoebeg i Auchteraw 8 A B862 O r e Hybrids/Wider tyres iv 787 R Meall Allt Doe DESCRIPTION (some unsealed stony Damh Inchnacardoch Forest sections) al an Ardachy C n Wood ia TIME 3 hours - 4.5 hours n 82 o A d Dail a' Chuirn e h l Featured route ic a Glendoe Forest C O On-road / Traffic-free Doire r e Daraich v i Start / Finish R Newtown VIEW POINTS Bridge of National Cycle Network Loch On-road / Traffic-free Lundie Oich FORT AUGUSTUS Coill B National816 Cycle Network Daingean River Route number Munerigie Fassie Aberchalder 712 Spot height (in metres) Attractive views from the Wood Tarff A A87 Munerigie Castle Attraction town and along Loch Ness Loch Garry Wood 2 Water Nursery 8 A A 8 7 Wood Foreshore och Oich ABERCHALDER Coille Invergarry L Coille Land Bolinn Invergarry Coille 529 Old stone suspension bridge, a' Ghlinne Dhubh Castle Mullach Wooded area Mandally a’ Ghlinne B sweeping vistas along the Mandally Urban area e Wood h c i Great Glen l l 2 (PH33 6BS) i 8 Hospital 891 a A C Glengarry Forest Aberchalder Forest Corrieyairack a Shop n Hill lt Al LAGGAN LOCKS Station Coille Doire Public Toilet Face Shlugan Chluain Views of the canal and Loch Wood Car Parking C Laggan 881 View Point 901 South Carn Leac Picnic Area Ben Tee Laggan Corrieyairack Forest Ghlais Laggan Forest hoire C a' C 816 Access Restriction Allt ROUTE PROFILE (RETURN) 2 Carn 8 WARNING Kilfinnan A McDonell Mausoleum Dearg Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right (2019). -

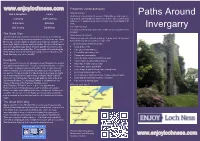

Paths Around Invergarry

www.enjoylochness.com Frequently asked questions What shall I take? Bed & Breakfasts Hotels Paths Around Stout shoes or boots are best as some of the paths go over rough or wet ground. Take waterproofs just in case it rains. Take a snack and a Camping Self Catering drink too. It ’ s always a good excuse to stop for a rest and admire the Attractions Activities view. Site Seeing Exhibitions Can I take my dog? Invergarry Yes but please keep dogs under close control or on a lead if there are livestock The Great Glen What else should I know? The Great Glen slices Scotland in two from Inverness to Fort William. Check your map and route before you go. If going alone, let someone Glaciers sheared along an underlying fault line 20,000 years ago, during know where you are going and your return time. the Ice Age, to carve out the U-shaped valley that today contains Loch ......and the Country and Forest Code? Ness, Loch Oich, Loch Lochy and Loch Linnhe. The Great Glen formed an ancient travelling route across Scotland and the first visitors to this Avoid all risk of fire area probably came along the Glen. Today, people still travel along the Take all your litter with you Great Glen by boat on the Caledonian Canal, on foot or bicycle on the Go carefully on country roads Great Glen way or by car on the A82. Please park considerately Leave livestock, crops and machinery alone Invergarry Follow advice about forestry operations On the old road to Skye, is the gateway to scenic Glengarry, the ancient Help keep all water sources clean stronghold of Clan Macdonnell.