Eilean Shona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Day Highlands and Isle of Skye Tour

5 day Highlands and Isle of Skye Tour Day 1 Our first stop is the mighty Stirling Castle and Wallace Monument. This commanding position at the foot of the Highland boundary has been fought over for thousands of years as a strategic point to control the entire country. We continue north/west into the Stirling Castle mountain wilderness to visit Etive Mor, an extinct super volcano known locally as “the Shepard of Glencoe”. Here we turn off the beaten path into Glen Etive for spectacular scenery and hopefully spot Red Deer in their native habitat. Next stop is Scotland’s most desired spot, Glencoe. Towering mountains on all sides and a bloody history make this an unforgettable experience to all who visit Glencoe Our final port of call is the town of Fort William at the foot of Britain’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis. (Fort William will be our overnight stop). Day 2 We start the day with a visit to Thomas Telford’s engineering masterpiece, Neptune’s staircase. Constructed 200 years ago it’s part of the Caledonian Canal system. This series of 8 locks lifts boats some 70 ft from the sea level to Loch Lochy above. We then head west to Glenfinnan and Loch Shiel for one of Scotland’s finest views. Here we will see the Glenfinnan and Loch Sheil Glenfinnan viaduct which featured in Harry Potter and the Jacobite memorial. We continue along the spectacular road to the Isles and catch a ferry for the short journey from Mallaig to the Isle of Skye. In Skye we visit Armadale castle. -

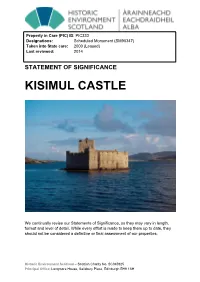

Kisimul Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC333 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90347) Taken into State care: 2000 (Leased) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KISIMUL CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KISIMUL CASTLE SYNOPSIS Kisimul Castle (Caisteal Chiosmuil) stands on a small island in Castle Bay, at the south end of the island of Barra and a short distance off-shore of the town of Castlebay. -

Highland C2C – Glenelg to Stonehaven 7 Stanes Skills Weekend

Highland C2C – Glenelg to Stonehaven Summary Duration: This epic coast to coast mountain biking trip, beginning on the rugged west coast of 8 nights’ accommodation mainland Scotland and ending on the sandy shores of the North Sea, offers 7 days of wilderness biking everything that the adventurous mountain biker could want. From the rocky crags of the Glen Shiel mountains to the massive expanse of the Cairngorms, this biking Average Daily Distance: adventure packs in the most dramatic scenery that Scotland has to offer. The terrain varies from the gently undulating singletrack that zigzags through the beautiful 55 km or 34 miles Rothiemurchus Estate near Aviemore, to steep, rocky climbs through the wild Braes of Abernethy. This trip has the added option of beginning on the deserted west coast Includes: of the mystical Isle of Skye in an unforgettable 8 day, 9 night Highland Coast to Coast. 8 nights’ accommodation Baggage transfers Highlights The drive to the starting point of the trip through some of Scotland’s most dramatic SMBLA qualified expert scenery guide or comprehensive maps and directions Sweet singletrack through native Caledonian pine forests Spotting the rare and illusive native wildlife through the trees in Rothimurchus Estate Vehicle back up Rewarding views of Loch Ness from the formidable Corrieyairack Pass Transfers and transport Real Highland hospitality at every stage of your adventure Pick up and drop off from Example 8-Day Itinerary Glasgow or Edinburgh Day 1. Arrive in Scotland. Whether arriving by bus, train, boat or plane, we can pick you up and take you to Shiel Bridge, on the western edge of the Scottish mainland, Available on request: where you’ll spend the night. -

Free Church of Scotland

free church of scotland FREE CHURCH, SHIEL BRIDGE, GLENSHIEL, IV40 8HW Former Church Residential Conversion/Development Property Picturesque Views Popular Location Rare Opportunity OFFERS OVER £70,000 DESCRIPTION SERVICES The subjects comprise a traditional stone and slate single storey Mains water, electricity and septic tank drainage. Prospective building, which is currently used as a Free Church. The property purchasers must satisfy themselves on services to the property. was substantially renovated in the 1960s, including new floors PLANNING and roof. This is not a Listed Building. It is a prime opportunity to The property is considered to be suitable for residential conversion/ acquire a development project for the conversion/development development, subject to the relevant consents being obtained of an existing building to a residential dwelling, in a picturesque from the local authority. The property currently has a Class 10 location. The Church is set within an area of land extending to (non-residential institutions) Consent in terms of the Town and approximately 0.245 acre. Country Planning (Use Classes) (Scotland) Order 1997. Prospective LOCATION purchasers should make their own planning enquiries with The Shiel Bridge is a village on the south east mouth of Loch Duich Highland Council on 01349 886608. in the west highlands area of Lochalsh. The A87 road passes RATEABLE VALUE through the village, continuing along the north coast of Loch Listed in the Valuation Roll online as Church - RV £1,600. Where Duich, passing Dornie and on to Kyle of Lochalsh. The property there is a Change of Use, the subjects will be reassessed for non- enjoys panoramic views over Loch Duich and is an ideal spot domestic rates or council tax, as appropriate. -

BOURBLAIG FAMILIES at the TIME of the CLEARANCES

BOURBLAIG FAMILIES at the TIME of the CLEARANCES A search of baptism records available through the Scotland’s People data base reveals eleven families who were at Bourblaig at some time between 1800 and 1828: Hugh Stewart and Christian (Christina also known as Christy) Henderson of Buorblaig baptized: Isobel 11 Oct 1802 Margaret 12Jun 1807 Sarah 6Feb 1811 Dugald Stewart and Ann Stewart of Buorblaig baptized: Dugald born 17Apr 1803 Kenneth 16Oct 1810 Dugald Stewart and Mary McLachlan of Buorblaig baptized: Charles 21May 1803 Angus 31Aug 1805 Ann 15Dec 1810 John Stewart and Ann McLachlan of Buorblaig baptized: John 26May 1807 Mary 21Apr1809 Ann 17Mar 1811 Allan 13Mar 1815 Anne 21Sep 1817 Isobel 19Apr 1820 John Stewart and Mary Stewart (Cameron) of Buorblaig baptized: Mary 10Feb 1822 Dugald 10Nov 1823 Dugald Carmichael and Beth McLachline of Buorblaig baptized: John born 29Sep 1803 Dugald Cameron and Ann McDonald of Buorblaig baptized: Donald 24May 1807 John McDonald and Anne Cameron of Buorblaig baptized: Ewen 15Jul 1821 Alexander McIntyre and Anne Stewart of Buorblaig baptized: John 23Aug 1821 Allan McDonald and Anne McGilvray of Buorblaig baptized: Archibald 18Nov 1821 Ewen McKenzie and Kate McDonald of Buorblaig baptized: Mary 10Dec 1821 Of the eleven families listed above five are Stewarts, plus the family of Alexander McIntyre and Anne Stewart has a Stewart as a family member. We know Alexander, John and Duncan Dugald and possibly other Stewarts were at Bourblaig in 1782 from Ardnamurchan Estate records. We also know at least three families were still at Bourblaig for a short period after the Clearance from records of baptism: McColl, the man responsible for evicting the families from Bourblaig, was granted a tenancy at nearby Tornamona. -

Fort-William-And-Lochaber.Pdf

Moidart 5 4 Ardnamurchan Sunart 3 2 Morvern Mull The diversity of Lochaber’s landscape is Sunart to the strip of shops and cafés in perfectly illustrated when you leave the Tobermory on the Isle of Mull. mountainous scenery of Glencoe and It’s an island feel that only adds to the Glen Nevis for the lonely and dramatic attraction – there are few places in Britain quarter of Ardgour, Moidart and the more alluring than here and the range of Ardnamurchan Peninsula. wildlife is almost without compare. The Stretching west from Loch Linnhe to oakwoods near Strontian are one of the Ardnamurchan Point, the most westerly best places to spot wildlife, as is the tip of the British mainland, this part of stunning coastline and white sandy Lochaber is sparsely populated with its beaches between Portuairk at the south villages linked by a string of mostly end of Sanna Bay and the lighthouse at single-track roads, meaning getting Ardnamurchan Point. anywhere can take a while. The craggy slopes of Ben Hiant offer Being surrounded on three sides by breathtaking views across much of this water gives this region a distinctly island region as well as over to the islands of quality – the most popular way onto the Mull, Rum and Eigg, while a lower but peninsula is by the Corran Ferry over Loch equally impressive vantage point can be Linnhe to Ardgour where five minutes on taken in from the Crofter’s Wood above the water transports you to the much Camusnagaul, a short ferry journey across more peaceful, laid-back pace of the Loch Linnhe from Fort William. -

Addyman Archaeology

Mingary Castle Ardnamurchan, Argyll Analytical and Historical Assessment for Tertia and Donald Houston December 2012 Detail from a survey of c1734 by John Cowley (NRS) Addyman Archaeology Building Historians & Archaeologists a division of Simpson & Brown Architects St Ninians Manse Quayside Street Edinburgh Eh6 6EJ Telephone 0131 554 6412 Facsimile 0131 553 4576 [email protected] www.simpsonandbrown.co.uk Mingary Castle, Ardnamurchan, Argyll Mingary Castle Ardnamurchan, Argyll Analytical and historical assessment By Tom Addyman and Richard Oram Contents 1. Introduction i. General ii. Methodology 2. Mingary Castle, the MacIans and the Lordship of Ardnamurchan Richard Oram i. Introduction ii. The Historiography of Mingary Castle iii. The Lordship of Ardnamurchan to c.1350 iv. The MacIans v. MacIan Inheritance and the Rise of Campbell Power 1519-1612 vi. Civil War to the Jacobite Era vii. Conclusion 3. Cartographic, early visual sources and visitors’ accounts 4. Earlier analyses of Mingary Castle i. Introduction ii. MacGibbon and Ross iii. W Douglas Simpson (1938-54) iv. RCAHMS (1970-80) v. More recent assessment 5. Description and structural analysis i. Introduction - methodology ii. Geology, building materials and character of construction th iii. The early castle (mid-late 13 century) a. General b. The early curtain c. Entrance arrangements d. Site of hall range e. Other features of the interior f. Possible well or cistern g. The early wall heads and parapet walk th iv. Later medieval – 16 century a. Introduction b. Hall range c. Garderobe tower d. Wall head remodelling to N e. Modifications to the wall head defences to the west, south and SE f. -

Pericles Coastal Interpretation

PERICLES Title Text Coastal Interpretation Webinar Myles Farnbank Head of Guides & Training for Wilderness Scotland Scotland Manager for Wilderness Foundation UK Vice-chair Scottish Adventure Activities Forum (SAAF) 30 years experience as an international wilderness guide - Mountain, sailing, sea kayaking, canoeing and wildlife guiding Created UK’s first Guide Training Programme in 2009 Active guide trainer throughout UK & internationally Lecturer Adventure Tourism, Marine & Coastal Tourism & Ecotourism Sit on Cross-party Working Group Recreational Boating & Marine Tourism - Scottish Parliament Introductions If everyone could introduce themselves and give a brief reason for attending todays webinar What is Scottish Coastal Cultural History? In break out groups - 15 minutes to note down anything that you feel is part of coastal Scotland’s cultural history story. You don’t have to agree - go ‘high low and wide’ Please agree someone in the group to scribe and feedback on the things you noted down Overview - morning session Context - Marine & Coastal Tourism What is Interpretation? Archaeology and brief history of the area Boundary or Bridge - psycho-geography of the coast Coastal Castles Coastal food & Net Product Whaling and seals Commerce and Culture Lost at Sea Lighting the way We are going to take a very wide view of coastal cultural history which will touch on most of the things you have shared. Overview - afternoon session Mystic Places - Folklore Coastal creations - art, music, poetry and prose Crofters and Fisherfolk - Personal stories from Mallaig & Arisaig We are going to take a very wide view of coastal cultural history which will touch on most of the things you have shared. -

Scotland's Road of Romance by Augustus Muir

SCOTLAND‟S ROAD OF ROMANCE TRAVELS IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF PRINCE CHARLIE by AUGUSTUS MUIR WITH 8 ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP METHUEN & CO. LTD. LONDON 36 Essex Street W,C, Contents Figure 1 - Doune Castle and the River Tieth ................................................................................ 3 Chapter I. The Beach at Borrodale ................................................................................................. 4 Figure 2 - Borrodale in Arisaig .................................................................................................... 8 Chapter II. Into Moidart ............................................................................................................... 15 Chapter III. The Cave by the Lochside ......................................................................................... 31 Chapter IV. The Road to Dalilea .................................................................................................. 40 Chapter V. By the Shore of Loch Shiel ........................................................................................ 53 Chapter VI. On The Isle of Shona ................................................................................................ 61 Figure 3 - Loch Moidart and Castle Tirrim ................................................................................. 63 Chapter VII. Glenfinnan .............................................................................................................. 68 Figure 4 - Glenfinnan .............................................................................................................. -

Official Statistics Publication for Scotland

Scotland’s Census 2011: Inhabited islands report 24 September 2015 An Official Statistics publication for Scotland. Official Statistics are produced to high professional standards set out in the Code of Practice for Official Statistics. © Crown Copyright 2015 National Records of Scotland 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Main Points .................................................................................................................... 4 3. Population and Households ......................................................................................... 8 4. Housing and Accommodation .................................................................................... 12 5. Health ........................................................................................................................... 15 6. Ethnicity, Identity, Language and Religion ............................................................... 16 7. Qualifications ............................................................................................................... 20 8. Labour market ............................................................................................................. 21 9. Transport ...................................................................................................................... 27 Appendices ..................................................................................................................... -

The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019

SCOTTISH STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2019 No. 56 FISHERIES RIVER SEA FISHERIES The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019 Made - - - - 18th February 2019 Laid before the Scottish Parliament 20th February 2019 Coming into force - - 1st April 2019 The Scottish Ministers make the following Regulations in exercise of the powers conferred by section 38(1) and (6)(b) and (c) and paragraphs 7(b) and 14(1) of schedule 1 of the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries (Consolidation) (Scotland) Act 2003( a) and all other powers enabling them to do so. In accordance with paragraphs 10, 11 and 14(1) of schedule 1 of that Act they have consulted such persons as they considered appropriate, directed that notice be given of the general effect of these Regulations and considered representations and objections made. Citation and Commencement 1. These Regulations may be cited as the Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Amendment Regulations 2019 and come into force on 1 April 2019. Amendment of the Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016 2. —(1) The Conservation of Salmon (Scotland) Regulations 2016( b) are amended in accordance with paragraphs (2) to (4). (2) In regulation 3(2) (prohibition on retaining salmon), for “paragraphs (2A) and (3)” substitute “paragraph (3)”. (3) Omit regulation 3(2A). (a) 2003 asp 15. Section 38 was amended by section 29 of the Aquaculture and Fisheries (Scotland) Act 2013 (asp 7). (b) S.S.I. 2016/115 as amended by S.S.I. 2016/392 and S.S.I. 2018/37. (4) For schedule 2 (inland waters: prohibition on retaining salmon), substitute the schedule set out in the schedule of these Regulations. -

THE PLACE-NAMES of ARGYLL Other Works by H

/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE PLACE-NAMES OF ARGYLL Other Works by H. Cameron Gillies^ M.D. Published by David Nutt, 57-59 Long Acre, London The Elements of Gaelic Grammar Second Edition considerably Enlarged Cloth, 3s. 6d. SOME PRESS NOTICES " We heartily commend this book."—Glasgow Herald. " Far and the best Gaelic Grammar."— News. " away Highland Of far more value than its price."—Oban Times. "Well hased in a study of the historical development of the language."—Scotsman. "Dr. Gillies' work is e.\cellent." — Frce»ia7is " Joiifnal. A work of outstanding value." — Highland Times. " Cannot fail to be of great utility." —Northern Chronicle. "Tha an Dotair coir air cur nan Gaidheal fo chomain nihoir."—Mactalla, Cape Breton. The Interpretation of Disease Part L The Meaning of Pain. Price is. nett. „ IL The Lessons of Acute Disease. Price is. neU. „ IIL Rest. Price is. nef/. " His treatise abounds in common sense."—British Medical Journal. "There is evidence that the author is a man who has not only read good books but has the power of thinking for himself, and of expressing the result of thought and reading in clear, strong prose. His subject is an interesting one, and full of difficulties both to the man of science and the moralist."—National Observer. "The busy practitioner will find a good deal of thought for his quiet moments in this work."— y^e Hospital Gazette. "Treated in an extremely able manner."-— The Bookman. "The attempt of a clear and original mind to explain and profit by the lessons of disease."— The Hospital.