Supplemental Readings and Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class Struggles in France 1848-1850

Karl Marx The Class Struggles in France, 1848-1850 Written: December January-October 1850; Published: as a booklet by Engels in 1895; Source: Selected Works, Volume 1, Progress Publishers, Moscow 1969; Proofed: and corrected by Matthew Carmody, 2009, Mark Harris 2010; Transcribed: by Louis Proyect. Table of Contents Introduction (Engels, 1895) ......................................................................................................... 1 Part I: The Defeat of June 1848 ................................................................................................. 15 Part II: From June 1848 to June 13, 1849 .................................................................................. 31 Part III: Consequences of June 13, 1849 ................................................................................... 50 Part IV: The Abolition of Universal Suffrage in 1850 .............................................................. 70 Introduction (Engels, 1895)1 The work republished here was Marx’s first attempt to explain a piece of contemporary history by means of his materialist conception, on the basis of the prevailing economic situation. In the Communist Manifesto, the theory was applied in broad outline to the whole of modern history; in the articles by Marx and myself in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, it was constantly used to interpret political events of the day. Here, on the other hand, the question was to demonstrate the inner causal connection in the course of a development which extended over some years, a development -

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

La Dame Aux Camelias' Effect on Society's View of the “Fallen Woman”

The Kabod Volume 2 Issue 2 Spring 2016 Article 7 January 2016 La Dame aux Camelias’ Effect on Society’s View of the “Fallen Woman” Christiana Johnson Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/kabod Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the French and Francophone Literature Commons Recommended Citations MLA: Johnson, Christiana "La Dame aux Camelias’ Effect on Society’s View of the “Fallen Woman”," The Kabod 2. 2 (2016) Article 7. Liberty University Digital Commons. Web. [xx Month xxxx]. APA: Johnson, Christiana (2016) "La Dame aux Camelias’ Effect on Society’s View of the “Fallen Woman”" The Kabod 2( 2 (2016)), Article 7. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/kabod/vol2/iss2/7 Turabian: Johnson, Christiana "La Dame aux Camelias’ Effect on Society’s View of the “Fallen Woman”" The Kabod 2 , no. 2 2016 (2016) Accessed [Month x, xxxx]. Liberty University Digital Commons. This Individual Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kabod by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Johnson: La Dame aux Camelias’ and the Fallen Woman Johnson 1 Christiana Johnson Dr. Towles English 305-001 19 November 2015 La Dame aux Camelias’ Effect on Society’s View of the “Fallen Woman” Over the course of history, literature has featured the “fallen woman.” Put simply, the “fallen woman” is a woman who has had sexual relations prior to marriage and is thus viewed as beneath a certain moral standard. -

Paris Region Facts & Figures 2021

Paris Region Facts & Figures 2021 Welcome to Paris Region Europe’s Leading Business and Innovation Powerhouse Paris Region Facts and Figures 2021 lays out a panorama of the Region’s economic dynamism and social life, positioning it among the leading regions in Europe and worldwide. Despite the global pandemic, the figures presented in this publication do not yet measure the impact of the health crisis, as the data reflects the reality of the previous months or year.* With its fundamental key indicators, the brochure, “Paris Region Facts and Figures 2021,” is a tool for decision and action for companies and economic stakeholders. It is useful to economic and political leaders of the Region and to all who wish to have a global vision of this dynamic regional economy. Paris Region Facts and Figures 2021 is a collaborative publication produced by Choose Paris Region, L’Institut Paris Region, and the Paris Île-de-France Regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry. *L’Institut Paris Region has produced a specific note on the effects of the pandemic on the Paris Region economy: How Covid-19 is forcing us to transform the economic model for The Paris Region, February 2021 Cover: © Yann Rabanier / Choose Paris Region 2nd cover: © Pierre-Yves Brunaud / L’Institut Paris Region © Yann Rabanier / Choose Paris Region Table of contents Welcome to Paris Region 5 Overview 6 Population 10 Economy and Business 12 Employment 18 Education 20 R&D and Innovation 24 Digital Infrastructure 27 Real Estate 28 Transport and Mobility 30 Logistics 32 Meetings and Exhibitions 34 Tourism and Quality of life 36 Welcome to Paris Region A Dynamic and A Thriving Business Paris Region, Fast-growing Region and Research Community A cultural and intellectual The highest GDP in the EU28 in A Vibrant, Innovative metropolis, a scientific and billions of euros. -

Quaderni Musicali Marchigiani 14

Quaderni Musicali Marchigiani 14 a cura di Concetta Assenza Pubblicazione dell’A.Ri.M. – Associazione Marchigiana per la Ricerca e Valorizzazione delle Fonti Musicali QUADERNI MUSICALI MARCHIGIANI 14/2016 a cura di Concetta Assenza ASSOCIAZIONE MARCHIGIANA PER LA RICERCA E VALORIZZAZIONE DELLE FONTI MUSICALI (A.Ri.M. – onlus) via P. Bonopera, 55 – 60019 Senigallia www.arimonlus.it [email protected] QUADERNI MUSICALI MARCHIGIANI Volume 14 Comitato di redazione Concetta Assenza, Graziano Ballerini, Lucia Fava, Riccardo Graciotti, Gabriele Moroni Realizzazione grafica: Filippo Pantaleoni ISSN 2421-5732 ASSOCIAZIONE MARCHIGIANA PER LA RICERCA E VALORIZZAZIONE DELLE FONTI MUSICALI (A.Ri.M. – onlus) QUADERNI MUSICALI MARCHIGIANI Volume 14 a cura di Concetta Assenza In copertina: Particolare dell’affresco di Lorenzo D’Alessandro,Madonna orante col Bambino e angeli musicanti, 1483. Sarnano (MC), Chiesa di Santa Maria di Piazza. La redazione del volume è stata chiusa il 30 giugno 2016 Copyright ©2016 by A.Ri.M. – onlus Diritti di traduzione, riproduzione e adattamento totale o parziale e con qualsiasi mezzo, riservati per tutti i Paesi. «Quaderni Musicali Marchigiani» – nota Lo sviluppo dell’editoria digitale, il crescente numero delle riviste online, l’allargamento del pubblico collegato a internet, la potenziale visibilità globale e non da ultimo l’abbattimento dei costi hanno spinto anche i «Quaderni Musicali Marchigiani» a trasformarsi in rivista online. Le direttrici che guidano la Rivista rimangono sostanzialmente le stesse: particolare attenzione alle fonti musicali presenti in Regione o collegabili alle Marche, rifiuto del campanilismo e ricerca delle connessioni tra storia locale e dimensione nazionale ed extra-nazionale, apertura verso le nuove tendenze di ricerca, impostazione scientifica dei lavori. -

Ninon De Lenclos

NINON DE LENCLOS ET LES PRÉCIEUSES DE LA PLACE ROYALE PAR JEAN-BAPTISTE CAPEFIGUE. PARIS - AMYOT - 1864 I. — Le Marais, la place Royale et la rue Saint-Antoine (1614-1630). II . — Louis XIII. - Sa cour. - Sa maison. - Les Mousquetaires (1604-1630). III . — Les premiers amours du roi Louis XIII (1619-1620). IV . — Les Perles du Marais sous Louis XIII (1614-1630). V. — Mlle de la Fayette. - Le cardinal de Richelieu. - Le grand écuyer Cinq-Mars (1630-1635). VI . — La vie religieuse à Paris.- Les couvents. - Les Carmélites. - Les Visitandines. - Mme Chantal. - Saint Vincent de Paul. Mlle de la Fayette au monastère (1614- 1630). VII . — La société joyeuse et littéraire de Paris sous Louis XIII (1625-1635). VIII . — Dictature du cardinal de Richelieu. - Rapprochement de Louis XIII avec la reine. - Exécution de Cinq-Mars (1639-1642). IX . — Les arts sous Louis XIII. - Rubens. - Poussin. Lesueur. - Callot (1635-1642). X. — La place Royale après la mort du cardinal de Richelieu (1642-1646). XI . — Le Marais. - Le faubourg Saint-Antoine durant la Fronde (1648-1650). XII . — Restauration du pouvoir. - Les premières amours de Louis XIV. - Les filles d'honneur de Madame. - Mlle de la Vallière (1655-1665). XIII . — Décadence de l'esprit frondeur. - Servilité des arts et de la littérature sous Louis XIV (1660-1680). XIV . — Derniers débris de la Fronde et de la place Royale (1665-1669). XV . — Les destinées du Marais et du faubourg Saint- Antoine (1714-1860). Il est un vieux quartier de Paris que nous aimons à visiter comme on salue d'un doux respect, une aïeule bien pimpante, bien attifée avec l'esprit de Mme de Sévigné, le charme de la marquise de Créquy ; ce quartier, c'est le Marais. -

NIKKI S. LEE Born 1970, Seoul, South Korea Lives and Works in Seoul, South Korea

VARIOUS SMALL FIRES, LOS ANGELES / SEOUL [email protected] / +1 310 426 8040 VSF [email protected] / +82 70 8884 0107 NIKKI S. LEE Born 1970, Seoul, South Korea Lives and works in Seoul, South Korea Education 1998 MA, Photography, New York University, New York, NY 1993 BFA, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, South Korea Solo Exhibitions 2019 Parts and Scenes, Various Small Fires, Los Angeles, CA 2015 Yours, One and J. Gallery, Seoul, South Korea 2011 Nikki S. Lee: Projects, Parts and Layers, One and J Gallery, Seoul, South Korea, May 19 – June 19, 2011. 2008 Layers, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY 2007 Nikki S. Lee: Projects and Parts, GAK, Bremen, Germany 2006 LT/Shoreham Gallery, New York, NY 2005 Galerie Anita Beckers, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO 2004 Numark Gallery, Washington, D.C. 2003 The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York, NY Nikki S. Lee, Printemps de Septembre, Toulouse, France 2002 Galerîa Senda, Barcelona, Sapin Clough-Hanson Gallery, Rhodes College, Memphis, TN 2001 Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York, NY The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, CA Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, IL 2000 Gallery Gan, Tokyo, Japan Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, UK 1999 Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York, NY Film Screenings 2015 Pink Panther, Oracle, Berlin, Germany 2011 Persona: A Body in Parts, Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC 2010 Home Movies, Platform: Centre for Photographic & Digital Arts, Winnipeg, Canada 2008 Mistaken Identities, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA Insa Art Center, Seoul, Korea 2007 Museum of Fine Arts, Houston , TX Saint Louis Art Museum, St. -

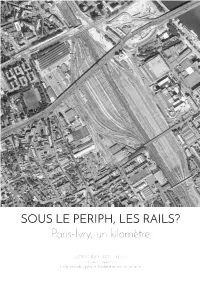

SOUS LE PERIPH, LES RAILS? Paris-Ivry, Un Kilomètre

SOUS LE PERIPH, LES RAILS? Paris-Ivry, un kilomètre WORKSHOP EUROPEEN N°4 du 17 au 24 février 2017 Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture Paris-Val de Seine 240 étudiants de Master 1 soit 6 groupes d’environ 40 étudiants inscrits dans tous les domaines d’études partic- ipent au Workshop. Chaque groupe est encadré par un des architectes-enseignants invités. 240 students in first year of master therefore six groups of 40 students studying in all fields of study. Each group is working with a specific invited architect - teacher. Workshop européen n° 4 du 17 février au 24 février 2017 SOUS LE PÉRIPH, LES RAILS? Paris-Ivry, un kilomètre Architectes- enseignants invités Guest architects - teachers Aljosa DEKLEVA Gulia MARINO (Ljubljana, Slovénie) (Lausanne, Suisse) Frédéric FLOQUET Olivier RAFFAELLI (Valence, Espagne) (Sao Paulo, Brésil, Paris) Richard MANAHL Jonathan WOODROFFE (Vienne, Autriche) (Londres, Angleterre) Groupe de pilotage enseignant Teacher Team Marie-Hélène Badia Dragoslav Mirkovic Cyrille Faivre Dominique Pinon (coordinateur) Brigit de Kosmi Nathalie Regnier-Kagan Sylvia Lacaisse Donato Severo Pierre Léger Marco Tabet Michel Lévi Ludovic Vion Moniteurs étudiants en binôme Student instructors Armelle Breuil Flora-Lou Leclair Colombe Crouan Sophie Loyer Thomas Gabriel Fares Makhlouf Théo Gruss- Koskas Julie Ondo Lucile Ink Florent Paoli Victor Le Forestier Philippe Robart 3 SOMMAIRE SUMMARY 01 Organisation de la semaine 7 Week Organization 02 Objectifs pédagogiques 11 Educational goals 03 Présentation des architectes invités -

5. Danutė Petrauskaitė

5. Danutė PETRAuskaitė Lietuvos muzikologija, t. 9, 2008 Danutė PetrauskaitĖ Danutė PetrauskaitĖ Lithuanian Passages in Music and Life of Foreign Composers Lietuviški pasažai užsienio kompozitorių gyvenime ir kūryboje Abstract For a number of years (1795–1918), Lithuania did not exist as a sovereign European country as a result of long-term wars and occupa- tions. However, the name of Lithuania was directly or indirectly reflected in the works of foreign composers. The aim of the article is to identify the connections of the 19th and 20th centuries foreign composers and Lithuania, and the way those connections were reflected in their music. This article is addressed to foreign readers who are willing to learn about the image of Lithuania in the context of the European musical culture. Keywords: music, Lithuania, Italy, Poland, Russia, Lithuania Minor, composer, song, opera. Anotacija Daugelį metų (1795–1918) Lietuva neegzistavo kaip suvereni Europos valstybė. Tai buvo ilgai trukusių karų ir okupacijų padarinys. Tačiau Lietuva tiesiogiai ar netiesiogiai darė įtaką užsienio šalių kompozitoriams. Šio straipsnio tikslas – nustatyti ryšius, siejusius XIX– XX a. ne lietuvių kilmės kompozitorius su Lietuva, ir kaip tie ryšiai atsispindėjo jų muzikoje. Jis yra labiau skirtas ne Lietuvos, bet užsienio skaitytojams, norintiems susipažinti su Lietuvos įvaizdžiu Europos muzikinės kultūros kontekste. Reikšminiai žodžiai: muzika, Lietuva, Italija, Lenkija, Rusija, Mažoji Lietuva, kompozitorius, daina, opera. Introduction Western Lithuania, the land of dark forests where people are driven by wild passions. Even though 140 years passed International interest in Lithuania dates back a thou- since the short story was written, in 2007, the American sand years, when it was merely a pagan land. -

Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations

G o zzi m a int a ine d th a t th ere ca n b e but thirty- six tra gic s a o s . e oo ea a s t o find o e h e was itu ti n Schill r t k gr t p in " m r , but e e . un abl e t o find eve n so m any as G ozzi . G o th Th e Thirty - Six Dram atic Situ ations GE ORGES POLTI Transl a ted by Lucil e R ay a o Fr nklin , Ohi J A M ES K NAPP H E R V E 1 9 2 4 PY H 1 9 1 6 1 9 1 7 CO RI G T , , T H E E D ITO R CO M PAN Y P H 1 92 1 CO YRI G T , JAM E S KN APP R E E VE 2 839 6 T H E T H I R TY - SI X D R AMAT I C SITUAT I ONS I NTR OD U CTI ON G o zzi m a int a in ed th a t th ere can b e but thirty - six tra gic s a o s . e o o ea a s t o fin o e h e itu ti n Schill r t k gr t p in d m r , but was a e s s un bl t o find even o m a ny a G o zzi . - Th irty six situations only ! There is , to me , some a thing t ntalizing about the assertion , unaccompanied as it is by any explanation either from Gozzi , or from Goethe or Schiller , and presenting a problem which it does not solve . -

Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected]

Nineteenth-Century Music Review, 14 (2017), pp 211–242. © Cambridge University Press, 2016 doi:10.1017/S1479409816000082 First published online 8 September 2016 Romantic Nostalgia and Wagnerismo During the Age of Verismo: The Case of Alberto Franchetti* Davide Ceriani Rowan University Email: [email protected] The world premiere of Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana on 17 May 1890 immediately became a central event in Italy’s recent operatic history. As contemporary music critic and composer, Francesco D’Arcais, wrote: Maybe for the first time, at least in quite a while, learned people, the audience and the press shared the same opinion on an opera. [Composers] called upon to choose the works to be staged, among those presented for the Sonzogno [opera] competition, immediately picked Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana as one of the best; the audience awarded this composer triumphal honours, and the press 1 unanimously praised it to the heavens. D’Arcais acknowledged Mascagni’smeritsbut,inthesamearticle,alsourgedcaution in too enthusiastically festooning the work with critical laurels: the dangers of excessive adulation had already become alarmingly apparent in numerous ill-starred precedents. In the two decades prior to its premiere, several other Italian composers similarly attained outstanding critical and popular success with a single work, but were later unable to emulate their earlier achievements. Among these composers were Filippo Marchetti (Ruy Blas, 1869), Stefano Gobatti (IGoti, 1873), Arrigo Boito (with the revised version of Mefistofele, 1875), Amilcare Ponchielli (La Gioconda, 1876) and Giovanni Bottesini (Ero e Leandro, 1879). Once again, and more than a decade after Bottesini’s one-hit wonder, D’Arcais found himself wondering whether in Mascagni ‘We [Italians] have finally [found] … the legitimate successor to [our] great composers, the person 2 who will perpetuate our musical glory?’ This hoary nationalist interrogative returned in 1890 like an old-fashioned curse. -

Francesco Cherubini

FRANCESCO CHERUBINI. TRE ANNI A MILANO PER CHERUBINI NELLA DIALETTOLOGIA ITALIANA Consonanze 14 Un doppio bicentenario è stato occasione di un’ampia riflessio- ne sulla figura e l’opera di Francesco Cherubini: i duecento anni, nel 2014, del primo Vocabolario milanese-italiano, e gli altrettanti, compiuti due anni dopo, della Collezione delle migliori opere scritte in dialetto milanese. Dai lavori qui raccolti si ridefinisce il profilo di uno studioso, un linguista, non riducibile all’autore di uno stru- FRANCESCO CHERUBINI mento lessicografico su cui s’affaticava spesso con insoddisfazio- ne Manzoni. Il mondo e la cultura della Milano della prima metà dell’Ottocento emergono dalle pagine dei vocabolari cherubiniani TRE ANNI A MILANO PER CHERUBINI e ne emerge anche più nitida la figura dell’autore, non solo ottimo NELLA DIALETTOLOGIA ITALIANA lessicografo ma anche dialettologo tra i più acuti della sua epoca, di un linguista che nessun aspetto degli studi linguistici sembra allontanare da sé. Ma rileggere Cherubini significa anche non sot- ATTI DEI CONVEGNI 2014-2016 trarsi a una riflessione sulla letteratura dialettale: a partire dunque dalla Collezione la terza parte del volume è dedicata ai dialetti d’I- talia come lingue di poesia. A cura di Silvia Morgana e Mario Piotti Silvia Morgana ha insegnato Dialettologia italiana e Storia della lingua italia- na nell’Università degli studi di Milano. Sulla lingua e la cultura milanese e lombarda ha pubblicato molti lavori e un profilo storico complessivo (Storia linguistica di Milano, Roma, Carocci, 2012). Mario Piotti insegna Linguistica italiana e Linguistica dei media all’Università degli Studi di Milano.