The Latin American Musicologist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dorset-Opera-News-Christmas-2008

News Issue No: 7 Christmas 2008 Audience numbers And for 2009 it’s… Artistic Director, Roderick Kennedy, has chosen two unashamedly double in 2 years! popular works for Dorset Opera’s 2009 presentation: the most famous twins in all opera, Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana and Leoncavallo’s I pagliacci. Dorset Opera audience numbers have officially doubled over the last two years! Leonardo Capalbo as Nadir We might only operate on a small scale, but in a sparsely populated county like Dorset, such an increase is no mean feat. Opera companies around the world can only dream of such a marketing success. However, if audience numbers continue to increase at this rate, it is estimated that the demand for tickets will require us to present at least six performances by 2012. This would be extremely difficult to schedule, so from 2009 onwards, tickets could be in short supply. Ticket shortage There is already evidence that regular audience-goers are aware of a possible ticket shortage. More and more supporters are joining Cav and Pag as they are affectionately known, contain a mass of our Friends’ organisation in order to take advantage of priority well-known tunes for our chorus to get their teeth in to, and for our booking arrangements. loyal audiences to savour. The Easter Hymn, the Internezzo, and Santuzza’s aria Voi lo sapete… from Cav; the Prologue from Pag is The Pearl Fishers: we can dance, as well as sing! in every baritone’s repertoire, and the heart-rending tenor aria Vesti la giubba translated as On with the Motley, is sure to leave a tear in the eye. -

Programme Notes Olivia Sham

Programme Notes Olivia Sham FRANZ LISZT Années de pèlerinage Book II – Italie (1811-1886) 1. Sposalizio 2. Il penseroso 3. Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Andante Favori WoO57 (1770-1827) CARL VINE Piano Sonata no.1 (b.1954) ~ Interval ~ OLIVIER MESSIAEN Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus (1908-1992) 11. ‘Première communion de la vierge’ CLAUDE DEBUSSY Préludes Book II (1862-1918) 10. Canope 6. General Lavine – Eccentric FRANZ LISZT Années de pèlerinage Book II – Italie 4. Sonnetto 47 del Petrarca 5. Sonnetto 104 del Petrarca 6. Sonnetto 123 del Petrarca 7. Aprés une lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata Having nothing to seek in present-day Italy, I began to scour her past; having but little to ask of the living, I questioned the dead. A vast field opened before me… In this privileged country I came upon the beautiful in the purest and sublimest forms. Art showed itself to me in the full range of its splendour; revealed itself in all its unity and universality. With every day that passed, feeling and reflection brought me to a still greater awareness of the secret link between works of genius…. Franz Liszt in 1839 (Translation by Adrian Williams) Before embarking on a touring career that would cement his reputation as the greatest of piano virtuosi, the young Franz Liszt travelled in Switzerland and Italy between 1837 and 1839 with his lover, the Countess Marie d’Agoult. He began then the first two books of the Années de Pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage), and the second volume of pieces, inspired by his time in Italy, was eventually published in 1858. -

A Retrotradução De C. Paula Barros Para O Português Das Óperas Indianistas O Guarani E O Escravo, De Carlos Gomes

A retrotradução de C. Paula Barros para o português das óperas indianistas O Guarani e O Escravo, de Carlos Gomes Daniel Padilha Pacheco da Costa* Overture Em 1936, as celebrações do centenário de nascimento de Carlos Gomes (1836- 1896), o mais célebre compositor brasileiro de óperas, foram rodeadas de tribu- tos. A ideologia nacionalista do varguismo não perdeu a oportunidade oferecida pela efeméride. Na época, foram publicadas diversas obras sobre Carlos Gomes, como o número especial da Revista Brasileira de Música de 1936, exclusivamente dedicado ao compositor campineiro, além das biografias A Vida de Carlos Gomes (1937), de Ítala Gomes Vaz de Carvalho (sua filha), e Carlos Gomes (1937), de Renato Almeida. No mesmo contexto, foram encenadas diversas composições de Carlos Gomes, dentre as quais se destacam as representações em português 10.17771/PUCRio.TradRev.45913 de sua ópera mais conhecida, Il Guarany (1870), com libreto de Antônio Scalvini e Carlo d’Ormeville. O conde Afonso Celso, presidente da Academia Brasileira de Letras, pro- moveu a apresentação da versão brasileira de O Guarani, em forma de concerto, no Teatro Municipal do Rio de Janeiro, em 7 de junho de 1935. Em forma de ópera baile, essa versão foi encenada uma única vez, no dia 20 de maio de 1937, pela Orquestra, pelos Coros e pelo Corpo de Baile do Teatro Municipal do Rio de Janeiro. A récita foi patrocinada pelo presidente Getúlio Vargas e regida pelo * Universidade Federal de Uberândia (UFU). Submetido em 25/09/2019 Aceito em 20/10/2019 COSTA A retrotradução de C. Paula Barros maestro Angelo Ferrari.1 Ao tomar conhecimento da representação em portu- guês, a filha do compositor foi aos jornais protestar contra uma traducã̧ o que “desvirtuaria” a composição do pai. -

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

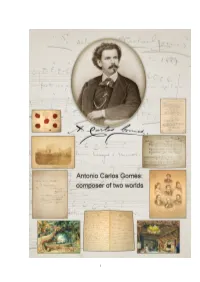

1 Nomination form International Memory of the World Register Antonio Carlos Gomes: composer of two worlds ID[ 2016-73] 1.0 Summary (max 200 words) Antonio Carlos Gomes: composer of two worlds gathers together documents that are accepted, not only by academic institutions, but also because they are mentioned in publications, newspapers, radio and TV programs, by a large part of the populace; this fact reinforces the symbolic value of the collective memory. However, documents produced by the composer, now submitted to the MOW have never before been presented as a homogeneous whole, capable of throwing light on the life and work on this – considered the composer of the Americas – of the greatest international prominence. Carlos Gomes had his works, notably in the operatic field, presented at the best known theatres of Europe and the Americas and with great success, starting with the world première of his third opera – Il Guarany – at the Teatro alla Scala – in Milan on March 18, 1870. From then onwards, he searched for originality in music which, until then, was still dependent and influenced by Italian opera. As a result he projected Brazil in the international music panorama and entered history as the most important non-European opera composer. This documentation then constitutes a source of inestimable value for the study of music of the second half of the XIX Century. 2.0 Nominator 2.1 Name of nominator (person or organization) Arquivo Nacional (AN) - Ministério da Justiça - (Brasil) Escola de Música da Universidade Federal do Rio de -

William Shakespeare E a Teoria Dos Dois Corpos Do Rei: a Tragédia De Ricardo II DOUTORADO EM CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO PUC-SP José Renato Ferraz da Silveira William Shakespeare e a teoria dos Dois Corpos do Rei: a tragédia de Ricardo II DOUTORADO EM CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS SÃO PAULO 2009 José Renato Ferraz da Silveira William Shakespeare e a teoria dos Dois Corpos do Rei: a tragédia de Ricardo II DOUTORADO EM CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências Sociais, Política, sob a orientação do Prof. Doutor Miguel Wady Chaia. SÃO PAULO 2009 Banca Examinadora _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ DEDICATÓRIA Dedico principalmente a Deus. Aos meus pais. Aos meus irmãos, companheiros inseparáveis. E, principalmente ao meu orientador e amigo Prof. Dr. Miguel Wady Chaia. AGRADECIMENTOS A Deus, fonte inesgotável de minha inspiração. Aos meus pais, pelo incentivo e compreensão. Aos meus irmãos, Fernando e Isabel. A Miguel e Vera Chaia. Aos colegas do NEAMP. À Márcia, pelo carinho e afeto. À Juliana, lembrança eterna e gravada no coração. À CNPQ, pela bolsa concedida nesses frutíferos anos de pesquisa. Ao Danilo da Cás e à Teresa Cristina Bruno Andrade, pela ajuda no processo de revisão do texto. RESUMO A tragédia da política é a certeza do inesperado, a constante reposição de energias humanas, o esforço para evitar o inevitável, a busca da ordem e da harmonia em face do desequilíbrio e do caos. Por meio de pesquisa teórica, este estudo volta-se para o entendimento acerca do impactante e devastador significado de política como tragédia, em que buscamos, com base na Hermenêutica, enfocar, relacionar, analisar o tempo histórico da obra de William Shakespeare, o governo do rei inglês Ricardo II, além da controversa teoria do direito divino dos reis – reforçada, discutida e ampliada – pelos juristas ingleses durante o governo da rainha Elisabeth (1558-1603). -

Carlos Gomes (1836-1896) a Música De Carlos Gomes, De Temática

Carlos Gomes (1836-1896) A música de Carlos Gomes, de temática brasileira e estilo italiano inspirado basicamente nas óperas de Giuseppe Verdi, ultrapassou as fronteiras do Brasil e triunfou junto ao público europeu. Antônio Carlos Gomes nasceu em Campinas SP, em 11 de julho de 1836. Estudou música com o pai e fez sucesso em São Paulo com o Hino acadêmico e com a modinha Quem sabe? ("Tão longe, de mim distante"), de 1860. Continuou os estudos no conservatório do Rio de Janeiro, onde foram apresentadas suas primeiras óperas: A noite do castelo (1861), com libreto de Fernandes dos Reis, e Joana de Flandres (1863), com libreto de Salvador de Mendonça. Com uma bolsa do conservatório, estudou em Milão com Lauro Rossi e diplomou-se em 1866. Em 19 de março de 1870 estreou no Teatro Scala de Milão sua ópera mais conhecida, Il guarany (O guarani), com libreto de Antonio Scalvini e baseada no romance homônimo de José de Alencar. Encenada depois nas principais capitais européias, essa ópera consagrou o autor e deu-lhe a reputação de um dos maiores compositores líricos da época. O sucesso europeu de Il guarany repetiu-se no Brasil, onde Carlos Gomes permaneceu por alguns meses antes de retornar a Milão, com uma bolsa de D. Pedro II, para iniciar a composição da Fosca, melodrama em quatro atos em que fez uso do Leitmotiv, técnica então inovadora, e que estreou em 1873 no Scala. Mal recebida pelo público e pela crítica, essa viria a ser considerada mais tarde como a mais importante de suas obras. -

Brasiliananúmero 9 / Setembro De 2001 / R$ 6,5O REVISTA QUADRIMESTRAL DA ACADEMIA BRASILEIRA DE MÚSICA

ISSN 1516-2427 BraSiliananúmero 9 / setembro de 2001 / R$ 6,5o REVISTA QUADRIMESTRAL DA ACADEMIA BRASILEIRA DE MÚSICA O Órgão da Catedral da Sé de Mariana Interpretação e Voz Um Réquiem para Villa-Lobos Atividades da Academia Lançamentos de Cds Henrique Morelenbaum *Vicente Sanes '° Roberto Duarte Vieira Brandão Edoardo de Guarnieri Maria Lúcia Godoy Ãcademia (Brasileira de Música Pede 1945 a serviço da música no (13 rasír Diretoria: Edino Krieger tpresidentel, Euribio Santos (vice-presidente), Ernani Aguiar (1 secretario), Roberto Duarte (2" secretario). Jose Maria Neves (1" tesoureiro), Mercedes Reis Pequeno (2 tesoureira) Comissão de Contas: Titulares - Vicente Salles, Mario Ficarelli, Raul daValle Suplentes- Manuel Veiga, Jamary de Oliveira. - Cadeira Patrono Fundador Sucessores 1. José de Anchieta Villa-Lobos Ademar Nóbrega - Marlos Nobre 2. Luiz Álvares Pinto Fructuoso Vianna Waldemar Henrique - Vicente Salles 3. Domingos Caldas Barbosa Jayme Ovalle e Radamés Gnattali Bidu Sayão - Cecilia Conde 4. J. J. E. Lobo de Mesquita Oneyda Alvarenga Ernani Aguiar 5. José Maurício Nunes Garcia Fr. Pedro Sinzig Pe. João Batista Lehmann - Cleofe Person de Mattos 6. Sigismund Neukommm Garcia de Miranda Neto Ernst Mahle 7.. Francisco Manuel da Silvg Martin Braunwieser Mercedes Reis Pequeno 8. Dom Pedro I Luis Cosme José Siqueira - Arnaldo Senise 9. Thomáz Cantuária Paulino Chaves Brasílio Itiberê - Osvaldo Lacerda 10. Cândido Ignácio da Silvá Octavio Maul Armando Albuquerque - Régis Duprat 11. Domingos R. Mossorunga Savino de Benedictis Mário Ficarelli 12. José Maria Xavier Otavio Bevilacqua José Maria Neves I 3. José Amat Paulo Silva-e Andrade Muricy Ronaldo Miranda 14. Elias Álvares Lobo Dinorá de Carvalho Eudóxia de Barros 15. -

A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS of LISZT's SETTINGS of the THREE PETRARCHAN SONNETS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North T

$791 I' ' Ac A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF LISZT'S SETTINGS OF THE THREE PETRARCHAN SONNETS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Johan van der Merwe, B. M. Denton, Texas December, 1975 van der Merwe, Johan, A Stylistic Analysis of Liszt's Settings of the Petrarchan Sonnets. Master of Arts (Music), December, 1975, 78 pp., 31 examples, appendix, 6 pp., biblio- graphy, 64 titles. This is a stylistic study of the four versions of Liszt's Three Petrarchan Sonnets with special emphasis on the revi- sion of poetic settings to the music. The various revisions over four versions from 1838 to 1861 reflect Liszt's artis- tic development as seen especially in his use of melody, harmony, tonality, color, tone painting, atmosphere, and form. His use of the voice and development of piano tech- nique also play an important part in these sonnets. The sonnets were inexplicably linked with the fateful events in his life and were in a way an image of this most flamboyant and controversial personality. This study suggests Liszt's importance as an innovator, and his influence on later trends should not be underestimated. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS..........0.... ..... .... iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION. ......... ......... 1 II. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF LISZT'S SETTINGS OF THE THREE PETRARCHAN SONNETS......a..... 13 Sonnet no. 47, "Benedetto sia '1 giorno" Sonnet no. 104, "Pace non trovo" Sonnet no. 123, "I' vidi in terra angelici costumi" III. CONCLUSION . .*.* .0.0 .a . -

Senior Recital: Christina Ruth Grace Vehar, Mezzo-Soprano

Kennesaw State University School of Music Senior Recital Christina Ruth Grace Vehar, mezzo-soprano Brenda Brent, piano Sunday, May 7, 2017 at 4 pm Music Building Recital Hall Seventieth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program I. GIOVANNI PERGOLESI (1710-1736) Se tu m’ami SALVATOR ROSA (1615-1673) Star Vicino GIOVANNI BATTISTA BONONCINI (1670-1747) Non posso disperar II. GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) Rêve d'amour HENRI DUPARC (1848-1933) Chanson Triste GABRIEL FAURÉ (1845-1924) Au bord de l'eau III. WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756-1791) Das Veilchen FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) An Die Musik ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) Widmung IV. HENRY PURCELL (1659-1695) Nymphs and Shepherds THOMAS ARNE (1710-1778) When Daisies Pied SAMUEL BARBER (1910-1981) The Daisies JOHN DUKE (1899-1984) Loveliest of Trees V. JOHN NEWTON (1725-1807) DOLLY PARTON (b. 1942) arr. Craig Hella Johnson Amazing Grace / Light of a Clear Blue Morning Alison Mann, conductor Choir: Emily Bateman, Emma Bryant, Benjamin Cubitt, Brittany Griffith, Cody Hixon, Chase Law, Caty Mae Loomis, Angee McKee, Rick McKee, Shannan O'Dowd, Marielle Reed, Hannah Smith, Forrest Starr This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree Bachelor of Music in Music Education. Ms. Vehar studies voice with Eileen Moremen. program notes I. Se tu m’ami | Giovanni Pergolesi Pergolesi was a composer known for his church music, his most popular being Stabat Mater – which became the most printed composition in the 1700s. He also found posthumous success for his opera La serva pedrona. The aria Se tu m’ami sets the scene of a young woman teasing a shepherd, and Pergolesi enhances this story through an ABA (ternary) form with the A section portraying the young woman and the B section portraying the frustrated shepherd boy. -

Salvator Rosa in French Literature: from the Bizarre to the Sublime

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Studies in Romance Languages Series University Press of Kentucky 2005 Salvator Rosa in French Literature: From the Bizarre to the Sublime James S. Patty Vanderbilt University Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/srls_book Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Preface i Salvator Rosa in French Literature ii Preface Studies in Romance Languages John E. Keller, Editor Preface iii Salvator Rosa in French Literature From the Bizarre to the Sublime James S. Patty THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY iv Preface Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2005 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patty, James S. -

Projeto Lo Schiavo

PROJETO LO SCHIAVO PROJETO LO SCHIAVO As intermitências da criação DENISE SCANDAROLLI Université de Paris IV (Paris-Sorbonne) [email protected] REVISTA MÚSICA | v. 13 | no 1, p. 155-186, ago. 2012 | 155 DENISE SCANDAROLLI RESUMO A importância da obra de Carlos Gomes na história da música e das artes no Brasil já é conhecida, por sua presença significativa nas mudanças estéticas e políticas do país. Em vista disso, este texto busca acompanhar o processo de criação da ópera Lo Schiavo a partir da correspondência do compositor e sua relação com a crítica musical. Os caminhos seguidos por Carlos Gomes na estruturação de suas músicas começam por desconstruir algumas de suas imagens fixadas pela historiografia e se abrem para uma nova perspectiva sobre como o processo de concepção da obra era pensada pelo compositor. palavras-chave: Carlos Gomes, Ópera, História do Brasil, Lo Schiavo 156 | REVISTA MÚSICA | v. 13 | no 1, p. 155-186, ago. 2012 PROJETO LO SCHIAVO LO SCHIAVO PROJECT: THE CREATION’S INTERMITTENCES ABSTRACT We already know the importance of Carlos Gomes’ work in the history of music and the arts in Brazil, due to his significant presence in the aesthetic and political changes in this country. Thus, this text follows the composition process of the opera Lo Schiavo departing from the composer’s correspondences and his relationships with the music critics of his time. The paths followed by Carlos Gomes in structuring his music are beginning to deconstruct some of the prejudices set by history and open a new perspective on how the conception of the work thought was conceived by the composer. -

Prelúdio De Maria Tudor”, De Carlos Gomes, E Da “Sinfonia De La Forza Del Destino”, De Verdi

XVI Congresso da Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós-graduação em Música (ANPPOM) Brasília – 2006 Estudo comparado da construção temática do “Prelúdio de Maria Tudor”, de Carlos Gomes, e da “Sinfonia de La Forza del Destino”, de Verdi Marcos Pupo Nogueira Instituto de Artes- Universidade Estadual Paulista- Unesp e-mail: [email protected] Sumário: O trabalho compara duas aberturas de ópera, o prelúdio de "Maria Tudor" de Carlos Gomes e a sinfonia de "La Forza del Destino" de Verdi, do ponto de vista da construção temática. Aponta as peculiaridades distintivas de Gomes quanto aos processos composicionais e indica caminhos para uma aproximação deste com o sinfonismo europeu do final do século XIX, no sentido de uma escrita temática coesa, baseada em transformações de motivos básicos, e mais afastado da vocalidade e do cantabile da ópera italiana do final do século XIX. Palavras-Chave: Carlos Gomes; Verdi; Aberturas; Estrutura temática e motívica. Introdução Carlos Gomes morou na Itália durante a maior parte da segunda metade do século XIX (1864-1896), período em que concluiu seus estudos musicais e estreou a maioria de suas óperas, convivendo e competindo profissionalmente com os principais criadores da cena lírica italiana, entre eles Ponchielli, Boito, Catalani, o jovem Puccini e especialmente Verdi. No entanto, à parte a inegável influência musical exercida por Verdi sobre o brasileiro (notadamente em suas primeiras óperas) Gomes desenvolveu, em vários aspectos da arte da composição musical, um estilo próprio. Nesse sentido, a análise de seu processo de construção temática conduz à revelação de sua singularidade em relação a outros compositores italianos, incluindo o próprio Verdi, objetivo deste trabalho.