Diplomarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDICA Management & Spezial Krankenhaus Zeitung Für Entscheider Im Gesundheitswesen

MEDICA Management & Spezial Krankenhaus Zeitung für Entscheider im Gesundheitswesen Oktober · 10/2011 · 30. Jahrgang Twittern und Co. für mehr Patienten „Time is brain“ Marktübersicht POCT Themen Facebook, Twitter und Google+ sind für Bei ersten Symptomen eines Schlaganfalls Was ist neu, was ist besser? Messtechnisch Gesundheitsökonomie Unternehmen keine Trends, sondern ernst- muss der Patient so schnell wie möglich in ausgereifte, moderne Geräte für die POCT Krankenhaus und Markenimage 5 zunehmenden Marketing-Instrumente. Auch eine spezialisierte Klinik gebracht werden. Diagnostik. Seite 32–34 Eine Klinik zu führen, heißt auch, sie im Kliniken werden kaum noch darauf verzich- Seite 11 Marktumfeld unverwechselbar zu ten können. Seite 4 positionieren. Medizin & Technik Mitarbeiter im Mittelpunkt 9 Initiative will erfahrene Mitarbeiter aus OP und Anästhesie in ihrem Tätigkeitsfeld halten und neue Fachkräfte gewinnen. Gezielte Tumorbestrahlung Hüftprothese - Pro und Contra 10 Ist ein Gelenk erhaltender operativer Eingriff sinnvoll und möglich? Die Stahlentherapie am Koronare Herzerkrankung 12 Universitätsklinikum Die Rolle der Echokardiographie bei Patienten mit koronarer Herzerkrankung Münster (UKM) erhält durch die Einweihung eines neuen IT & Kommunikation Lückenlose Bewegungsmuster 17 Beschleunigers neue und Energieeffiziente Chip-Technologien, Smartphones und Webplattformen als moderne Behandlungsmög- Basis mobiler Medical Monitoring Systeme FallAkte als Baukasten-System 20 lichkeiten. Dr. Jutta Jessen Der Verein elektronische FallAkte entwickelt mit dem Fraunhofer Institut für sprach mit der Leitenden Software- und Systemtechnik das Konzept „eFA in a box“. Oberärztin der Klinik für Strahlentherapie am UKM, Pharma Kürzere Bestrahlungszeiten, verbesserte Genauigkeit und höchste Leistungsfähigkeit Geschlechtsspezifische Medika- Dr. Iris Ernst. – Anfang August wurde der erste Patient mit dem neuen Gerät bestrahlt. mente 21 Neuste Ergebnisse zeigen einen deutlichen Unterschied im Stoffwechsel M&K: Was sind die besonderen Vorteile von Männern und Frauen. -

Katoomba Program 2015

The Workshop Film Group presents: The 40th Residential Film Weekend October 3 – October 5, 2015 Metropole Guest House, Katoomba. Saturday 3 October 2.00 Run Lola Run (Lola Rennt) Crime Thriller DVD (77 Mins) 3.40 The Searchers Western DVD (120 Mins) Dinner 6pm – 8pm 8.00 Seven Brides for Seven Brothers Musical DVD (102 Mins) 10.15 Stranger on the Third Floor Film Noir DVD (64 Mins) Sunday 4 October Breakfast 8 am – 9 am 9.00 East of Eden Drama DVD (112 Mins) 11.05 The War Game Documentary DVD (49 Mins) Lunch 12.00 pm – 1.45 pm 1.45 Molokai, The Story of Father Damien Drama DVD (120 Mins) 4.15 Art & Power 1937 Documentary DVD (28 Mins) 5.00 Cane Toads: An Unnatural History Documentary DVD (47 Mins) Dinner 6pm – 8pm 8.00 Above Suspicion Spy Drama DVD (90 Mins) 10.00 Green Tea & Cherry Ripe Documentary VHS (47 Mins) Monday 5 October Breakfast 8 am – 9 am 9.00 A Portrait of the Schulpor Robert Keppel Documentary DVD (54 Mins) 10.10 Suspicion Drama DVD (99 Mins) Lunch 12.05 pm – 1.45 pm 1.45 Lotte Reiniger (Dance Of Shadows) Animation DVD (60 Mins) NB. Provisional program – all the above films have been booked but the order of showing may change. They’re A Weird Mob (105 Mins) is a possible replacement for East of Eden but is available only in VHS, we are endeavouring to obtain quality details before considering a swap. Documentaries and shorts: GREEN TEA AND CHERRY RIPE Dir: Solrun Hoaas, Australia vhs 1988 54 mins, b&w and col, Japanse with English subtitles. -

MEJOR PELICULA 127 HOURS Christian Colson, Danny Boyle

MEJOR PELICULA 127 HOURS Christian Colson, Danny Boyle, John Smithson BLACK SWAN Mike Medavoy, Arnold Messer, Brian Oliver, Scott Franklin GREENBERG Scott Rudin, Jennifer Jason Leigh THE KIDS ARE ALL RIGHT Gary Gilbert, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, Celine Rattray, Jordan Horowitz, Daniela Taplin Lundberg, Philippe Hellmann WINTER´S BONE Alix Madigan-Yorkin, Anne Rosellini MEJOR DIRECTOR DARREN ARONOFSKY Black Swan DANNY BOYLE 127 Hours LISA CHODOLENKO The Kids are all right DEBRA GRANIK Winter´s Bone JOHN CAMERON MITCHELL Rabbit Hole MEJOR ÓPERA PRIMA EVERYTHING STRANGE AND NEW Frazer Bradshaw, Laura Techera Francia, A.D Liano GET LOW Aaron Schneider, Dean Zanuck, David Gundlach THE LAST EXORCISM Daniel Stamm, Eric Newman, Eli Roth, Marc Abraham, Thomas A. Bliss NIGHT CATCHES US Tanya Hamilton, Ronald Simons, Sean Costello, Jason Orans TINY FURNITURE Lena Dunham, Kyle Martin, Alicia Van Couvering PREMIO JOHN CASSAVETES DADDY LONGLEGS Josh Safdie, Benny Safdie, Casey Neistat, Tom Scott THE EXPLODING GIRL Bradley Rust Gray, So Yong Kim, Karin Chien, Ben Howe LBS Matthew Bonifacio, Carmine Famiglietti LOVERS OF HATE Bryan Poyser, Megan Gilbride OBSELIDIA Diane Bell, Chris Byrne, Matthew Medlin MEJOR GUIÓN LISA CHOLODENKO, STUART BLUMBERG The Kids are all right DEBRA GRANIK, ANNE ROSELLINI Winter´s Bone NICOLE HOLOFCENER Please Give DAVID LINDSAY-ABAIRE Rabbit Hole TODD SOLONDZ Life during wartime MEJOR GUIÓN DEBUTANTE DIANE BELL Obselidia LENA DUNHAM Tiny Furniture NIK FACKLER Lovely, Still ROBERT GLAUDINI Jack goes boating DANA ADAM SHAPIRO, EVAN M. WIENER Monogamy MEJOR ACTRIZ PROTAGÓNICA ANNETTE BENING The Kids are all right GRETA GERWIG Greenberg NICOLE KIDMAN Rabbit Hole JENNIFER LAWERENCE Winter´s Bone NATALIE PORTMAN Black Swan MICHELLE WILLIAMS Blue Valentine MEJOR ACTOR PROTAGÓNICO RONALD BRONSTEIN Daddy Longlegs AARON ECKHART Rabbit Hole JAMES FRANCO 127 Hours JOHN C. -

Tvtimes Are Calling Every Day Is Exceptional at Meadowood Call 812-336-7060 to Tour

-711663-1 HT AndyMohrHonda.com AndyMohrHyundai.com S. LIBERTY DRIVE BLOOMINGTON, IN THE HERALD-TIMES | THE TIMES-MAIL | THE REPORTER-TIMES | THE MOORESVILLE-DECATUR TIMES August 3 - 9, 2019 NEW ADVENTURES TVTIMES ARE CALLING EVERY DAY IS EXCEPTIONAL AT MEADOWOOD CALL 812-336-7060 TO TOUR. -577036-1 HT 2455 N. Tamarack Trail • Bloomington, IN 47408 812-336-7060 www.MeadowoodRetirement.com 2019 Pet ©2019 Five Star Senior Living Friendly Downsizing? CALL THE RESULTS TEAM Brokered by: | Call Jenivee 317-258-0995 or Lesaesa 812-360-3863 FREE DOWNSIZING Solving Medical Mysteries GUIDE “Flip or Flop” star and former cancer patient Tarek El -577307-1 Moussa is living proof behind the power of medical HT crowdsourcing – part of the focus of “Chasing the Cure,” a weekly live broadcast and 24/7 global digital platform, premiering Thursday at 9 p.m. on TNT and TBS. Senior Real Estate Specialist JENIVEE SCHOENHEIT LESA OLDHAM MILLER Expires 9/30/2019 (812) 214-4582 HT-698136-1 2019 T2 | THE TV TIMES| The Unacknowledged ‘Mother of Modern Dish Communications’ Bedford DirecTV Cable Mitchell Comcast Comcast Comcast New Wave New New Wave New Mooreville Indianapolis Indianapolis Bloomington Conversion Martinsviolle BY DAN RICE television for Lionsgate. “It is one of those rare initiatives that WTWO NBC E@ - - - - - - - With the availability, cost E# seeks to inspire with a larger S WAVE NBC - 3 - - - - - and quality of healthcare being $ A WTTV CBS E 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 humanitarian purpose, and T such hot-button issues these E^ WRTV ABC 6 6 6 6 - 6 6 URDAY, -

Kunst- Und Kulturbericht � Frauenkulturbericht � Der Stadt Wien � 2012 �

Kunst- und Kulturbericht � Frauenkulturbericht � der Stadt Wien � 2012 � Kunst- und Kulturbericht � Frauenkulturbericht � der Stadt Wien � 2012 � Herausgegeben von der � Geschäftsgruppe Kultur und Wissenschaft � des Magistrats der Stadt Wien � Amtsführender Stadtrat für Kultur und Wissenschaft � Dr. Andreas Mailath-Pokorny � Für den Inhalt verantwortlich: Dr. Bernhard Denscher – MA 7 Dr.in Brigitte Rigele – MA 8 Dr.in Sylvia Mattl-Wurm – MA 9 Dr. Nicolaus Schafhausen – KUNSTHALLE wien Mag.a Martina Taig – KÖR Kunst im öffentlichen Raum Wien Wolfgang Wais – Wiener Festwochen MMag.a Gerlinde Seitner – Filmfonds Wien Dr.in Marijana Stoisits – Vienna Film Commission Dr. Wolfgang Kos – Wien Museum Mag.a Karin Rick – Frauenkulturbericht Lektorat: Andrea Traxler Layout: Mag. Niko Manikas Cover: Eva Choung-Fux aus der Serie „Szymborska Night Picture“, 1998, Hochdruckgrafik Sammlung der Kulturabteilung der Stadt Wien – MUSA Covergestaltung: Mag. Niko Manikas Druck: AV+ Astoria Druckzentrum GmbH, Wien Redaktion: Mag.a Karin Rick Bezugsadresse: MA 7 – Kultur Friedrich-Schmidt-Platz 5 1082 Wien e-mail: [email protected] www.kultur.wien.at Inhalt KUNST- UND KULTURBERICHT .................................................................................... 9 � Kulturabteilung der Stadt Wien – MA 7 ........................................................................11 � Theater .....................................................................................................................11 � Wiener Festwochen ....................................................................................................12 -

Written by Ben Woolf Edited by Sam Maynard and Katherine Igoe-Ewer Rehearsal and Production Photography by Johan Persson CONTENTS BACKGROUNDPRODUCTIONRESOURCES

Written by Ben Woolf Edited by Sam Maynard and Katherine Igoe-Ewer Rehearsal and Production Photography by Johan Persson CONTENTS BACKGROUNDPRODUCTIONRESOURCES Contents Introduction 3 Section 1: Background to CLOSER 4 CLOSER: An introduction 5 Characters 6 CLOSER in Context 10 Section 2: The Donmar’s Production 15 Cast and Creative Team 16 Rehearsal Diaries 17 An Interview with Playwright Patrick Marber 21 An Interview with the Cast of CLOSER 26 Section 3: Resources 30 Spotlight on Deborah Andrews, Costume Supervisor 31 Workshop Exercises 35 Bibliography 39 2 CONTENTS BACKGROUNDPRODUCTIONRESOURCES Introduction Welcome to this Behind the Scenes Guide to the Donmar Warehouse production of Patrick Marber’s CLOSER, directed by David Leveaux. The following pages contain an exclusive insight into the process of bringing this production from page to stage. Written by playwright and director Patrick Marber, CLOSER was critically acclaimed when it premiered at the National Theatre in 1997, winning Olivier, Evening Standard and New York Drama Critic’s Circle Awards. It has since been produced in the West End, Broadway, around the world and adapted into an international movie. This is its first major London revival. This guide aims to set the play and the production in context. It includes conversations with Patrick Marber and the cast who bring the characters to life. There are also extracts from Resident Assistant Director Zoé Ford’s rehearsal diary and practical exercises designed for use in the classroom. The guide has a particular focus on costume and includes a conversation with Deborah Andrews, the production’s costume supervisor, whose role is crucial in finding the right look for each character. -

Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter's Theatre

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2010 Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1645 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2010 ii © 2010 GRAÇA CORRÊA All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Daniel Gerould ______________ ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Jean Graham-Jones Supervisory Committee ______________________________ Mary Ann Caws ______________________________ Daniel Gerould ______________________________ Jean Graham-Jones THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Synesthetic Landscapes in Harold Pinter’s Theatre: A Symbolist Legacy Graça Corrêa Adviser: Professor Daniel Gerould In the light of recent interdisciplinary critical approaches to landscape and space , and adopting phenomenological methods of sensory analysis, this dissertation explores interconnected or synesthetic sensory “scapes” in contemporary British playwright Harold Pinter’s theatre. By studying its dramatic landscapes and probing into their multi-sensory manifestations in line with Symbolist theory and aesthetics , I argue that Pinter’s theatre articulates an ecocritical stance and a micropolitical critique. -

KMFDM Kunst Mp3, Flac, Wma

KMFDM Kunst mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Kunst Country: Germany Released: 2013 Style: Alternative Rock, Industrial MP3 version RAR size: 1180 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1853 mb WMA version RAR size: 1600 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 808 Other Formats: AA AIFF MPC WAV AHX MIDI FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Kunst 5:01 2 Ave Maria 5:06 3 Quake 4:05 4 Hello 4:24 5 Next Big Thing 4:41 6 Pussy Riot 4:10 7 Pseudocide 3:36 8 Animal Out 5:06 The Mess You Made Feat. Morlocks 9 6:05 Featuring – Morlocks 10 I ♥ Not 4:32 Companies, etc. Licensed From – Metropolis Records – MET 851 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 4 042564 135480 Label Code: LC 10270 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year MET851D KMFDM Kunst (10xFile, MP3, Album, 320) Metropolis MET851D US 2013 MET851 KMFDM Kunst (LP, Album, Ltd) Metropolis MET851 US 2013 MET851 KMFDM Kunst (CD, Album) Metropolis MET851 US 2013 MET851D KMFDM Kunst (10xFile, FLAC, Album) Metropolis MET851D US 2013 MET 851D KMFDM Kunst (10xFile, ALAC, Album) Metropolis MET 851D US 2013 Comments about Kunst - KMFDM Malann I changed my previous review. Favorites songs are Kunst, Quake, and Next Big Thing. The_NiGGa wtf?! you better listen to Kunst once or twice again a bit more concentrated. KMFDM doesn't deserves a rezension of someone listening to it only once and then keep thinking he understood everything! Kunst has the typical kmfdm trademarks. Jules guitars sounds much more improved than before (if you like to hear Günter Schulz you should listen to slick idiot). -

Presumption of Innocence: Procedural Rights in Criminal Proceedings Social Fieldwork Research (FRANET)

Presumption of Innocence: procedural rights in criminal proceedings Social Fieldwork Research (FRANET) Country: GERMANY Contractor’s name: Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte e.V. Authors: Thorben Bredow, Lisa Fischer Reviewer: Petra Follmar-Otto Date: 27 May 2020 (Revised version: 20 August 2020; second revision: 28 August 2020) DISCLAIMER: This document was commissioned under contract as background material for a comparative analysis by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) for the project ‘Presumption of Innocence’. The information and views contained in the document do not necessarily reflect the views or the official position of the FRA. The document is made publicly available for transparency and information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or legal opinion. Table of Contents PART A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 1 PART B. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 4 B.1 PREPARATION OF FIELDWORK ........................................................................................... 4 B.2 IDENTIFICATION AND RECRUITMENT OF PARTICIPANTS ................................................... 4 B.3 SAMPLE AND DESCRIPTION OF FIELDWORK ...................................................................... 5 B.4 DATA ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................. -

Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad De Bellas Artes Aprendizaje De Lenguas Extranjeras (Inglés) a Través Del Teatro

Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad de Bellas Artes Aprendizaje de Lenguas Extranjeras (Inglés) a través del Teatro. Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad de Bellas Artes Proyecto de Grado Licenciatura en Artes Escénicas EL APRENDIZAJE DE UNA LENGUA EXTRANJERA (INGLÉS) A TRAVÉS DEL TEATRO Estudio de caso en el campo del teatro bilingüe: Grupo The E Theater de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia Presentado por: Camilo Suárez Ramos Asesor: Literato. Hernando Parra Rojas Bogotá D.C., Octubre de 2012 Camilo Suárez Ramos Proyecto de Grado en Artes escénicas 2 Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad de Bellas Artes Aprendizaje de Lenguas Extranjeras (Inglés) a través del Teatro. EL APRENDIZAJE DE UNA LENGUA EXTRANJERA (INGLÉS) A TRAVÉS DEL TEATRO Estudio de caso: Grupo The E Theater de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia Camilo Suárez Ramos Proyecto de Grado en Artes escénicas i Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad de Bellas Artes Aprendizaje de Lenguas Extranjeras (Inglés) a través del Teatro. FORMATO RESUMEN ANALÍTICO EN EDUCACIÓN - RAE Código: FOR020GIB Versión: 01 Fecha de Aprobación: 10-10-2012 Página ii de 144 1. Información General Tipo de documento Trabajo de grado Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. Biblioteca Facultad de Acceso al documento Bellas Artes Aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera (inglés) a través de Titulo del documento teatro. Autor(es) Suárez Ramos, Camilo. Director Parra Rojas, Hernando. Publicación Bogotá. Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. 2012. 136 p. Unidad Patrocinante Lenguas extranjeras, teatro, aprendizaje, -

To Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com4 x 2” ad Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! December 3 - 9, 2020 Sample sale: INSIDE: Offering: 1/2 off Hydrafacials Venus Legacy What’s new on • Treatments Netflix, Hulu & • BOTOX Call for details Amazon Prime • DYSPORT Pages 3, 17 & 22 • RF Microneedling • Body Contouring • B12 Complex • Lipolean Injections • Colorscience Products • Alastin Skincare Judge him if you must: Bryan Cranston Get Skinny with it! (904) 999-0977 plays a troubled ‘Your Honor’ www.SkinnyJax.comwww.SkinnyJax.com Bryan Cranston stars in the Showtime drama series “Your Honor,” premiering Sunday. 1361 13th Ave., Ste.1 x140 5” ad Jacksonville Beach NowTOP 7 is REASONS a great timeTO LIST to YOUR HOMEIt will WITH provide KATHLEEN your home: FLORYAN List Your Home for Sale • YOUComplimentary ALWAYS coverage RECEIVE: while the home is listed 1) MY UNDIVIDED ATTENTION – • An edge in the local market Kathleen Floryan LIST IT becauseno delegating buyers toprefer a “team to purchase member” a Broker Associate home2) A that FREE a HOMEseller stands SELLER behind WARRANTY • whileReduced Listed post-sale for Sale liability with [email protected] UNDER CONTRACT - DAY 1 ListSecure® 904-687-5146 WITH ME! 3) A FREE IN-HOME STAGING https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com PROFESSIONAL Evaluation BK3167010 I will provide you a FREE https://expressoffers.com/exp/kathleen-floryan 4) ACCESS to my Preferred Professional America’s Preferred Services List Ask me how to get cash offers on your home! 5) AHome 75 Point SELLERS Warranty CHECKLIST for for Preparing Your Home for Sale 6) ALWAYSyour Professionalhome when Photography we put– 3D, Drone, Floor Plans & More 7) Ait Comprehensive on the market. -

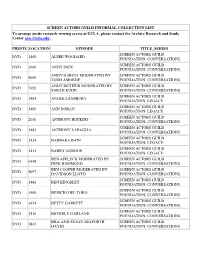

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST to Arrange Onsite Research Viewing Access at UCLA, Please Contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected]

SCREEN ACTORS GUILD INFORMAL COLLECTION LIST To arrange onsite research viewing access at UCLA, please contact the Archive Research and Study Center [email protected] . PREFIX LOCATION EPISODE TITLE_SERIES SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1460 ALFRE WOODARD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1669 ANDY DICK FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY GARCIA MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8699 TODD AMORDE FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS ANDY RICHTER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7020 SARAH KUHN FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1484 ANGLE LANSBURY FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1409 ANN DORAN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 2010 ANTHONY HOPKINS FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1483 ANTHONY LAPAGLIA FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1434 BARBARA BAIN FOUNDATION: LEGACY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1413 BARRY GORDON FOUNDATION: LEGACY BEN AFFLECK MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 6348 PETE HAMMOND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BEN COOPER MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 8697 DAVIDSON LLOYD FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1486 BEN KINGSLEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1500 BENICIO DEL TORO FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1674 BETTY GARRETT FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1416 BEVERLY GARLAND FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL AND SUSAN SEAFORTH SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 1843 HAYES FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS BILL PAXTON MODERATED BY SCREEN ACTORS GUILD DVD 7019 JENELLE RILEY FOUNDATION: CONVERSATIONS SCREEN ACTORS