The Right of Confrontation, Justice Scalia, and the Power and Limits of Textualism, 48 Wash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Achieve Like a Girl

SIMI VALLEY SAN FERNANDO CALABASAS AGOURA HILLS ANTELOPE VALLEY SIMI VALLEY SAN FERNANDO CALABASAS AGOURA HILLS ANTELOPE VALLEY 9.28.15_front_Layout 1 9/25/15 12:16 PM Page 1 ocbj.com ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL TM $1.50 VOL. 38 NO. 39 THE COMMUNITY OF BUSINESS SEPTEMBER 28-OCTOBER 4, 2015 INSIDE Achieve Like a Girl Innovators Honored 3 High-Profile OC Execs page 7 4321 Jamboree: Israel-based company recently com- Count Gold Award as Precursor mitted to lease extension through 2027 to Bountiful Careers By KIM HAMAN Out of Ordinary for There was a budding business mind behind the Newport Beach: cherubic face selling cookies door-to-door. It was 1968, and the face belonged to Cyd Brand- Factory Upgrade vein, a 10-year-old Girl Scout. She approached the assignment with determina- TECHNOLOGY: Chipmaker to put tion, knocking on every single door in her New York City apartment building, armed with a pitch and a $15M or more into plant on Jamboree Special Report smile. Brandvein: has gone from Ed Sullivan to AECOM, By CHRIS CASACCHIA T page 15 She sold 3,000 boxes of remained part of organization as director of OC Beyond Work Girl Scout cookies— chapter Israel-based Tower Semiconductor Ltd. is in- enough to earn her a guest spot on the “Ed Sullivan Show,” where along with vesting $15 million to $20 million to upgrade its other record-breaking cookie sellers, she sang the “God Bless America” accompanied by an orchestra Newport Beach manufacturing plant to meet led by the song’s composer, Irving Berlin. -

Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection

Search artists, albums and more... ' Explore + Marketplace + Community + * ) + Dashboard Collection Wantlist Lists Submissions Drafts Export Settings Search Collection ' Random Item Manage Folders Manage Custom Fields Change Currency Export My Collection Collection Value:* Min $3,698.90 Med $9,882.74 Max $29,014.80 Sort Artist A-Z Folder Keepers (500) Show 250 $ % & " Remove Selected Keepers (500) ! Move Selected Artist #, Title, Label, Year, Format Min Median Max Added Rating Notes Johnny Cash - American Recordings $43.37 $61.24 $105.63 over 5 years ago ((((( #366 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release American Recordings, American Recordings 9-45520-1, 1-45520 Near Mint (NM or M-) Shrink 1994 US Johnny Cash - At Folsom Prison $4.50 $29.97 $175.84 over 5 years ago ((((( #88 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album Very Good Plus (VG+) US 1st Release Columbia CS 9639 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1968 US Johnny Cash - With His Hot And Blue Guitar $34.99 $139.97 $221.60 about 1 year ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Mic Very Good Plus (VG+) top & spine clear taped Sun (9), Sun (9), Sun (9) 1220, LP-1220, LP 1220 Very Good (VG) 1957 US Joni Mitchell - Blue $4.00 $36.50 $129.95 over 6 years ago ((((( #30 on R.S. top 500 List LP, Album, Pit Near Mint (NM or M-) US 1st Release Reprise Records MS 2038 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1971 US Joni Mitchell - Clouds $4.03 $15.49 $106.30 over 2 years ago ((((( US 1st LP, Album, Ter Near Mint (NM or M-) Reprise Records RS 6341 Very Good Plus (VG+) 1969 US Joni Mitchell - Court And Spark $1.99 $5.98 $19.99 -

Reunification of Missing Children Training Manual

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Introduction • Overview of Current Missing Child Problem Reunification Reunification Project • Team issues of • Purpose of Training Manual Missing Children Non-Family Abduction • Case Study G Research Training Manual Parental Abduction • Case Study • Research Runaways Center for the Study of Trauma • Case Study Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute • Research University of California 9! San Francisco Child Trauma Review f (0<] Treatment of Child Trauma 11.1 Reunification of Missing Children Research Results 177' , ~ ._ .. _,._ > •• _~ __• ___• _, • __.i .~ References AVERY ~~/~~ PROGRAM GOALS Each year in the United States, more than 4,500 children disappear as a result of stranger and • non-family abduction, more than 350,000 disappear as aresultoffamily abduction, and more than 750,000 disappear as a result of a runaway event (NISMART, 1990). While the majority of these children are recovered, the process of return and reunification has often been difficult and frustrating. Less than 10% of these children and their families receive any kind of assistance and guidance in the reunification process (Hatcher, Barton, and Brooks, 1989). Further, the average length of time between the parents' appearance to pick up their recovered child and their departure to go home is only 15 minutes (Hatcher, Barton, and Brooks, ibid.). Professionals involved with these families, including investigating law enforcement officers, mental health/social service professionals, and victim/witness personnel, have all recognized the need for: (1) a knowledge base about missing children and their families, (2) a clearer understanding of the missing! abduction event and its consequences to chHd and family, and (3) guidelines and training to develop a coordinated multi-agency approach to assisting these child victims and theirfamilies. -

Firefighter Facing Cultivation Charges Ukiah Fire Department by BEN BROWN and Released on the Above Listed Noe

Ukiah High The Commerce PARNELL DIES IN PRISON boys basketball File Kidnapped Ukiah boy in 1980 .............Page 6 ..............Page 3 .....................................Page 2 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Tomorrow: Cool with rain; H 47º L 34º 7 58551 69301 0 WEDNESDAY Jan. 23, 2008 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 14 pages, Volume 149 Number 289 email: [email protected] Firefighter facing cultivation charges Ukiah Fire Department By BEN BROWN and released on the above listed Noe. The Daily Journal charges along with Jeffrey Weston and Noe said sheriff’s deputies were at Posted online captain, who also serves Three people, including a Ukiah Victor Villalobos after the three were the home in Canyon Court trying to at 3:56 p.m. on Fire District board, Fire Department captain, were arrest- found in a house in the 700 block of serve a felony warrant on Ashley Tuesday ed Friday on suspicion of marijuana Canyon Court that contained more Weston. two others arrested after cultivation. than 600 marijuana plants, said 648 marijuana plants found UFD Capt. Terry Israel was cited Mendocino County Sheriff’s Lt. Rusty See MARIJUANA, Page 14 ukiahdailyjournal.com Ukiah man held on sex Storm brings snow and drug charges Suspected of entering a stranger’s apartment and assaulting 5-year-old child The Daily Journal A Ukiah man who allegedly broke into a North State Street apartment, and was found lying on a couch in his underwear with a 5-year-old child, was arrested on sexual abuse and drug charges by the Ukiah Police Department at 5:30 a.m. -

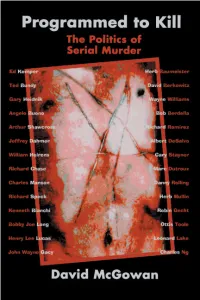

Programmed to Kill

PROGRAMMED TO KILL PROGRAMMED TO KILL The Politics of Serial Murder David McGowan iUniverse, Inc. New York Lincoln Shanghai Programmed to Kill The Politics of Serial Murder All Rights Reserved © 2004 by David McGowan No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. iUniverse, Inc. For information address: iUniverse, Inc. 2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100 Lincoln, NE 68512 www.iuniverse.com ISBN: 0-595-77446-6 Printed in the United States of America This book is for all the survivors. “This man, from the moment of conception, was programmed for murder.” —Attorney Ellis Rubin, speaking on behalf of serial killer Bobby Joe Long Contents Introduction: Mind Control 101 ................................................xi PART I: THE PEDOPHOCRACY Chapter 1 From Brussels… ......................................................3 Chapter 2 …to Washington ....................................................23 Chapter 3 Uncle Sam Wants Your Children ............................39 Chapter 4 McMolestation ......................................................46 Chapter 5 It Couldn’t Happen Here ........................................54 Chapter 6 Finders Keepers ......................................................59 PART II: THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT HENRY Chapter 7 Sympathy for the Devil ..........................................71 Chapter 8 Henry: -

National Sex Offender Registration Policies and the Unintended Consequences

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2021 National Sex Offender Registration Policies and the Unintended Consequences Sydney J. Selman University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the American Politics Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Society Commons, Political History Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, Social History Commons, and the Social Justice Commons Recommended Citation Selman, Sydney J., "National Sex Offender Registration Policies and the Unintended Consequences" (2021). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/2426 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. National Sex Offender Registration Policies and the Unintended Consequences Sydney J. Selman University of Tennessee, Knoxville 1 Acknowledgement Many thanks to my advisor, Dr. Anthony Nownes, for his advice and encouragement throughout this project. His expertise was invaluable, and I could not have completed this thesis without his constant feedback and support. I also owe special thanks to Dr. Michelle Brown, who first introduced me to punitive politics and reformative justice in her Sociology 456: Punishment and Society course. It is because of this class that I found a new perspective on social accountability and healing, inspiring me to dig deeper into how sex offender registrations took shape in the United States and how they may have gone too far. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Respect Interior F.Indd

Contents Foreword by Duke Fakir . xiii Introduction by M. L. Liebler and Jim Daniels. xv I. Detroit Jazz. Par adise Valley Days Mark James Andrews | Shot 3 Silenced the Singer: Th e Murder. .3 Glen Armstrong | Th e Last DJ . 000 Peter Balakian | Joe Louis’s Fist. 000 Melba Joyce Boyd | A Mingus Among Us and a Walden Within Us. 000 | Blow Marcus Blow . 000 | Th e Bass Is Woman . 000 | Working It Out. 000 Writer L. Bush | A Love Supreme . 000 Ginny Carr | He Was Th e Cat (A Tribute to Eddie Jeff erson) . 000 Esperanza Cintrón | Music -3 Th e African World Festival . 000 David Cope | River Rouge . 000 Diane DeCillis | Th e Girl from Ipanema Visits Detroit, 1964 . 000 Toi Derricotte | Blackbottom . 000 Bob “Detroit Count” White | Hastings Street Opera (Part One). 000 Aurora Harris | So Beautiful 9/5/2016 5:45 a.m. 000 Bill Harris | Ron Carter: Th e Pulse in Autumn . 000 Kaleema Hasan | Lost Bird: Take 2 . 000 Kim D. Hunter | the sound before . 000 George Kalamaras | Every Note You Play is a Blue Note . 000 James E. Kenyon | Autumn Leaves . 000 Michael Lauchlan | Raptor. 000 Philip Levine | I Remember Cliff ord . 000 | Th e Wrong Turn . 000 | Above Jazz. 000 | On Th e Corner . 000 M. L. Liebler | Th e Jazz . 000 Sonya Marie Pouncy | Musing I: Her Inspiration . 000 Eugene B. Redmond | Kwansaba: Rolling Late Sixties–Style Ntu Motor City . 000 John G. Rodwan Jr. | JC on the Set . 000 John Sinclair | “bags’ groove” . 000 Keith Taylor | Detroit Dancing, 1948. 000 Chris Tysh | By any means necessary . -

121101Lostsoulgems.Pdf

今より遡ること50年以上前、激動の1960年代、その後のポピュラー・ミュージックに多大な影響を与えたソウル・ミュージックが次々と生み出さ ソウルのレア・アルバムをリスティングするにあたってやはりこちらは外せないであろう王道中の王道、MOTOWN。ロック/ポップス系コレ れたわけですが、その中からジェームス・ブラウンの初期3作のように骨董品的価値がうなぎ登りなものから、モーメンツの別テイク盤のように クターからも熱い支持を得つづけているMOTOWN、そして傍系のTAMLA、GORDYの作品の中でも誰もが認める絶頂期、デトロイト・サウン 60s SOUL 過去数えるほどしか市場に姿を現していないものまで重要度の高いものを厳選ピックアップさせていただきました。 MOTOWN ドが迸る黄金の60年代のアイテムからピックアップ致しました。 THE CLOVERS THE COASTERS THE DELLS ETTA JAMES MARY WELLS BYE, BYE EDDIE HOLLAND MARY WELLS THE SUPREMES THE CLOVERS ONE BY ONE OH, WHAT A NITE AT LAST BABY / I DON'T WANT TO TAKE EDDIE HOLLAND T H E ON E W HO REA L LY MEET THE SUPREMES ATLANTIC / 1248 ATCO / 33-123 VEE-JAY / 1010 ARGO / 4003 A CHANCE MOTOWN / MLP-600 MOTOWN / MLP-604/MT-604 LOVES YOU MOTOWN / MT-605 MOTOWN / MT-606 U.S.オリジナル、 U.S.オリジナル、 U.S.オリジナル、 U.S.オリジナル、 U.S.オリジナル、 U.S.オリジナル、 U.S.オリジナル、 U.S.オリジナル、 MONO、黒銀 MONO、黄色ラ アズキ色と銀ラ MONO、ターコ MONOオンリー、 MONOオンリー、 MONOオンリー、 MONOオンリー、 ラ ベ ル 、溝 あ り 、 ベ ル 、琴 ロ ゴ 入 り 、 ベ ル 、溝 あ り 。発 イズ(青緑)ラベ 本盤のみのホワ MLP規格は モ ータウンの 初 スツー ル×大 文 1200番台初版、 初期ATLANT 表より半世紀過 ル 、溝 あ り 。没 後 イト・ラ ベ ル × ブ ホール上にアド 代女王の62年 字 ロ ゴ・ジ ャ ケ ッ 初期ATLANT ICの代表作。 ぎた今も重 厚な さらに希少価値 ル ー・ロ ゴ 、6 1 レ ス 、モ ー タ ウ セ カ ンド・ア ル バ ト、62年ファース IC盤の重厚感。 存在感を放つ が 高まって いる 年記念すべき ン・サ ウ ンド の ム。 ト・ア ル バ ム 。 処女作。 処女作。 モ ータウン初 ア 立役者のシン ルバム。 ガ ー・ア ル バ ム 。 買取価格 買取価格 買取価格 買取価格 買取価格 買取価格 買取価格 買取価格 ¥13,000 ¥8,000 ¥15,000 ¥15,000 ¥12,000 ¥8,000 ¥9,000 ¥30,000 GINO WASHINGTON GLADYS KNIGHT AND THE THE HEARTSTOPPERS HELENE SMITH THE MIRACLES MARVIN GAYE THE MIRACLES THE MARVELETTES GOLDEN HITS NOW PIPS LETTER FULL OF TEARS HEARTSTOPPERS SINGS SWEET SOUL HI, WE'RE THE MIRACLES THE SOULFUL MOODS OF COOKIN' WITH THE MIRACLES PLEASE MR. -

Zeiss Resigns from TWA Post Barbara Ward New Sanibel Principal

B28 August 3,1979 Island Reporter The Finest VOL. 6 NO. 40 SERVING SANIBEL-CAPTIVA AND THE ISLANDS FltOM ESTERO BAY TO THE CASPARILLAS ©Suncoost Publication. 1979 i<< -V on Sanibel Island Zeiss resigns Welcomes from TWA post By Bradley Fray > ; )'• Island Water Association (IWA) ection General Manager Ralph Zeiss, Jr. resigned on Wednesday from that II. K post, apparently at the request of the board of directors. 's days i The action came during a These are the 'dog days,' Wednesday board meeting and that hot period originally •(• reckoned as 20 days ;.•..••• Zeiss reportedly cleaned out his before to SO days after the It:': desk following the meeting. conjunction of Sirius, the FURNISHED MODELS Zeiss, who held the position just 'dog star,' and the sun. a little more than 10 months, has But all that doesn't slow OPEN 9 AM - 6 PM EVERY DAY been replaced by Ian Watson, who down Daisy, the beach also will continue his duties as loving mutt belonging to I IWA's chief engineer. Watson's ap- George and Fleur pointment by the board took effect Weymouth, on Wednesday. Zeiss, interviewed Wednesday night, would not comment on what © continued on 15-A Typo stalk bondvcdid(Mori By Nancy DelFavero The legal description of the property in Captiva the ordinance reads as a parcel in A single-character error, possibly "Township 46 South, Range 22 East, Sec- typographical, has stalled court validation tion 26, Township 46 Soufth, Range 22," of Sanibel's bond issue for the Causeway when in fact, the proper section number for Casa and Brown ("Algiers") properties. -

The World of SOUL PRICE: $1 25

BillboardTheSOUL WorldPRICE: of $1 25 Documenting the impact of Blues and R&Bupon ourmusical culture The Great Sound of Soul isonATLANTIC *Aretha Franklin *WilsonPickett Sledge *1°e16::::rifters* Percy *Young Rascals Estherc Phillipsi * Barbara.44Lewis Wi gal Sow B * rBotr ho*ethrserSE:t BUM S010111011 Henry(Dial) Clarence"Frogman" Sweet Inspirations * Benny Latimore (Dade) Ste tti L lBriglit *Pa JuniorWells he Bhiebelles aBel F M 1841 Broadway,ATLANTIC The Great Sound of Soul isonATCO Conley Arthur *KingCurtis * Jimmy Hughes (Fame) *BellE Mg DeOniaCkS" MaryWells capitols The pat FreemanlFamel DonVarner (SouthCamp) *Darrell Banks *Dee DeeSharp (SouthCamp) * AlJohnson * Percy Wiggins *-Clarence Carter(Fame) ATCONew York, N.Y. 10023 THE BLUES: A Document in Depth THIS,the first annual issue of The World of Soul, is the initial step by Billboard to document in depth the blues and its many derivatives. Blues, as a musical form, has had and continues to have a profound effect on the entire music industry, both in the United States and abroad. Blues constitute a rich cultural entity in its pure form; but its influence goes far beyond this-for itis the bedrock of jazz, the basis of much of folk and country music and it is closely akin to gospel. But finally and most importantly, blues and its derivatives- and the concept of soul-are major factors in today's pop music. In fact, it is no exaggeration to state flatly that blues, a truly American idiom, is the most pervasive element in American music COVER PHOTO today. Ray Charles symbolizes the World Therefore we have embarked on this study of blues. -

ED290209.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 290 209 EA 019 817 AUTHOR Wishon, Phillip M.; Broderius, Bruce W. TITLE Missing and Abducted Children: The School's Role in Prevention. Fastback 249. INSTITUTION Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Ind. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87367-249-6 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 58p.; Sponsored by the Mid-Cities/UTA (Texas) Chapter of Phi Delta Kappa. AVAILABLE FROMPublication Sales, Phi Delta Kappa, Eighth and Union, Box 789, Bloomington, IN 47402 ($.90). PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Child Advocacy; Child Neglect; *Child Welfare; *Crime Prevention; Criminals; Elementary Secondary Education; Law Enforcement; Parent Child Relationship; Rape; *Runaways; *School Responsibility; School Role; School Security; *Victims of Crime IDENTIFIERS Abductions; *Kidnapping; *Missing Children; Parent Kidnapping ABSTRACT The purpose of this pamphlet is to aid teachers, counselors, administrators, paraprofessionals, and other support personnel in alleviating the problem of missing and abducted children. After an introductory overview of the national incidence of missing children, three specific categories of missing childrenare identified and discussed: runaways, parent abductions, and abductions by unknown persons. The ensuing sections identifymeasures schools can take to prevent abductions: tracking students; identification of students; working with parents (including a list of 24 suggestions that schools should communicate to parents); working with students (including a list of 20 suggestions for children to helpensure their personal safety); and a checklist for making schools safe. Thenext sections provide steps to follow in reportinga child missing, reporting the discovery of a missing child, and reintegratingan abduction victim into the classroom. A brief bibliography is provided, and the following listsare appended: (1) U.S.