Nepal. Bronze, H:14 Inches, 15Th C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems in Dating Nepalese Metal Sculpture: Three Images of Viṣṇu (Corrected)

asianart.com | articles Asianart.com offers pdf versions of some articles for the convenience of our visitors and readers. These files should be printed for personal use only. Note that when you view the pdf on your computer in Adobe reader, the links to main image pages will be active: if clicked, the linked page will open in your browser if you are online. This article can be viewed online at: http://asianart.com/articles/visnu In 1984 this article was published in the Journal of the Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS) of Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu (vol. 12, No. 1, December 1984, pp 2349). In an article published in 2012, Gautam Vajracarya made an important correction to the dating of the first Visnu sculpture presented in this paper (Vajracharya, Gautam V, “Two Dated Nepali Bronzes and their Implications for the Art History of Nepal” in Indo Asiatische Zeitschrift 16, Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft fur IndoAsiatische Kunst, Berlin 2012 pp 418.) In the original article I had working with the help of the great epigraphist Dhanavajra Vajracarya, Gautam Vajracharya's uncle interpreted the inscription on the LACMA repousse Visnu plaque (fig. 1) to indicate the date NS 103, equal to 983 CE. Gautam Vajracharya corrected the interpretation of the original inscription (we are in agreement on the reading) to arrive at a more reasonable date, NS 300/1180 CE. I have included his reinterpretation of the inscription in a footnote below. This correction shows how over the years, those interested in the art history of Nepal have made consistent strides to better our understanding of this important tradition. -

Bibliography of the History and Culture of the Himalayan Region

Bibliography of the History and Culture of the Himalayan Region Volume Two Art Development Language and Linguistics Travel Accounts Bibliographies Bruce McCoy Owens Theodore Riccardi, Jr. Todd Thornton Lewis Table of Contents Volume II III. ART General Works on the Himalayan Region 6500 - 6670 Pakistan Himalayan Region 6671 - 6689 Kashmir Himalayan Region 6690 - 6798 General Works on the Indian Himalayan Region 6799 - 6832 North - West Indian Himalayan Region 6833 - 6854 (Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh) North - Ceritral and Eastern Indian Himalayan Region 6855 - 6878 (Bihar, Bengal, Assam, Nagaland, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim) Bhutan 6879 - 6885 Nepal 6886 - 7242 Tibet 7243 - 7327 IV. DEVELOPMENT General Works on India and the Pan-Himalayan Region 7500 - 7559 Pakistan Himalayan Region 7560 - 7566 Nepal 7567 - 7745 V. LANGUAGE and LINGUISTICS General Works on the Pan-Himalayan Region 7800 - 7846 Pakistan Himalayan Region 7847 - 7885 Kashmir Himalayan Region 7886 - 7948 1 V. LANGUAGE (continued) VII. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Indian Himlayan Region VIII. KEY-WORD GLOSSARY (Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Bengal, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, IX. SUPPLEMENTARY INDEX Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh) General Works 79.49 - 7972 Bhotic Languages 7973 - 7983 Indo-European Languages 7984 8005 Tibeto-Burmese Languages 8006 - 8066 Other Languages 8067 - 8082 Nepal General Works 8083 - 8117 Bhotic Languages 8118 -.8140 Indo-European. Languages 8141 - 8185 Tibeto-Burmese Languages 8186 - 8354 Other Languages 8355 - 8366 Tibet 8367 8389 Dictionaries 8390 - 8433 TRAVEL ACCOUNTS General Accounts of the Himalayan Region 8500 - 8516 Pakistan Himalayan Region 8517 - 8551 Kashmir Himalayan Region 8552 - 8582 North - West Indian Himalayan Region 8583 - 8594 North - East Indian Himalayan Region and Bhutan 8595 - 8604 Sikkim 8605 - 8613 Nepal 8614 - 8692 Tibet 8693 - 8732 3 III. -

Mary Shepherd Slusser (1918–2017)

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 38 Number 1 Article 22 June 2018 Obituary | Mary Shepherd Slusser (1918–2017) Gautama V. Vajracharya Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Vajracharya, Gautama V.. 2018. Obituary | Mary Shepherd Slusser (1918–2017). HIMALAYA 38(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol38/iss1/22 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Obituary | Mary Shepherd Slusser (1918–2017) Gautama V. Vajracharya It would take more than a full-length article to do justice in the mid 1970s in Artibus Asiae on medieval Nepalese to Mary Slusser’s contributions to the field of Nepalese culture, architecture, and history. cultural-historical and architectural studies. In this all From her training in anthropology, she was fully aware too brief tribute, I hope to provide the readers with a of the value of historiography, and approached the glimpse of her achievements. Mary modestly described subject diachronically and synchronically. In our joint herself as an enthusiast who ached to unravel the past. investigation of the art and culture of the Kathmandu She first arrived to Nepal in 1965 alongside her husband, Valley, we realized that some elements of ancient who worked in the foreign service and had been appointed Nepalese culture had remained intact in various aspects of there. -

John Siudmak Asian

JOHN SIUDMAK a s i a n a rt FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE LATE SIMON DIGBY 1 JOHN SIUDMAK a s i a n a rt Viewing by appointment only JOHN SIUDMAK Flat 3, 3 Sydney Street London SW3 6PU tel. +44 (0) 20 7349 9316 mob. +44 (0) 7918 730 936 email. [email protected] www.johnsiudmak.com This is the last assortment from the collection of the late Simon Digby. It mostly consists of modest pieces, which should be of interest to a wide audience. It gives an opportunity to those who don't have a lot of money to acquire desirable objects and especially to those who knew Simon directly. 1 1 TERRACOTTA IMAGE OF A STANDING FEMALE Senthen, Kashmir Wearing Hellenistic garments of belted chiton and ca. 50 BC/ 50AD himation, produced from a mould. Height: 11.6cm Note: This belongs to an intriguing group of terracotta images produced in Hellenistic and early Indian style, which was found exclusively in Kashmir at a site known as Semthan, near Bijbihara. For another example see Siudmak, 2013, chapter 2, part 1. Surprisingly, nothing comparable has been found in the neighbouring areas of Greek influence such as Taxila, Charsadda or Begram. £1,200 1 2 GREY SCHIST NIMBATE FIGURE OF HARITI Gandhara, Pakistan Seated in European style, holding a cornucopia in the raised left hand, the 4th/ 5th century right hand holding a globular pot and cover. Height: 12 .6cm £850 Note: It should be noted that the cornucopia in Gandhara art is depicted as an actual horn bearing fruit, cf. -

Masterworks a Journey Through Himalayan Art Large Labels

MASTERWORKS A JOURNEY THROUGH HIMALAYAN ART MODEL OF THE MAHABODHI TEMPLE Eastern India, probably Bodhgaya; ca. 11th century Stone (serpentinite) Rubin Museum of Art Purchased with funds from Ann and Matt Nimetz and Rubin Museum of Art C2019.2.2 According to Buddhist tradition, Bodhgaya is the place where the Buddha meditated under the bodhi tree and attained his awakened state. Mahabodhi Temple was built to commemorate this event at this site during the reign of Ashoka (ca. 268–232 BCE), the famed patron of Buddhism credited with building many temples and stupas. It attained the form seen in this model in the fifth to sixth century. A pilgrimage site revered across the Buddhist world, Mahabodhi Temple was often reproduced as portable pilgrimage souvenirs like this one. Such replicas also enshrined symbolic representations of the site, such as bodhi leaves, which were considered relics. Seeing a replica of the temple served as a substitute for those who couldn’t visit the site in person, and it acted as a symbol of remembrance for those who did. Small models like this one have been found in Burma and Tibet, and full-scale temple replicas were constructed in places like Nepal and Beijing. This model was likely created in Bodhgaya itself. It represents what the temple may have looked like in the eleventh century, shortly before it fell into ruin. 850 CROWNED BUDDHA Northeastern India; Pala period (750–1174), 10th century Stone Rubin Museum of Art C2013.14 For early Tibetan Buddhists the holy sites of northeastern India were important pilgrimage sites. -

Chapter 2 the Fire Ritual in a Newar Buddhist Context

25 2 3 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1. Research questions, aims and methods ......................................................................... 5 1.2. Sources: Visual materials ................................................................................................ 8 1.3. Sources: The Kriyāsaṃgrahapañjikā and a priest’s manual ........................................... 8 1.4. Sources: Anthropological accounts................................................................................. 9 1.5. Terminology .................................................................................................................. 10 Chapter 2 The fire ritual in a Newar Buddhist context ...................................................... 11 2.1. Homa as a tantric ritual and its place in Newar Buddhist practice .............................. 12 2.1.1. Tantric homa .......................................................................................................... 12 2.1.2. Classifying homa .................................................................................................... 13 2.1.3. Homa in Newar rituals of consecration ................................................................. 14 2.2. Key aspects of homa in Newar fire rituals .................................................................... 19 2.2.1. Actors: Priest and patron ...................................................................................... -

Ancient and Medieval Nepal

@ 1st Edition, 1960 D. R. Regmi, Kathmandu, Nepal. Published by K. L. MUKHOPADHYAY, 61 1 A, Banchharam Akrur Lane, Calcutta 12. India. Price : Rs. 15.00 Printed by R. Chatterjee, at the Bhani Printers Private Ltd., 38, Strand Road, Calcutta-1. m The Shrine of Pasupatinath from the western gate Jalasayana Vishnu ( 7th Century A. D. ) CONTENTS kist of Abbreviations Bibliography Map Foreword . Preface to the First Edition . Preface to the Second Edition . CHAPTERI1 : GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON SOME ASPECTS OF NEPALESE LIFE AND CULTURE The Antiquity of the Newars of Kathmandu . Kiatas in Ancient History . Their first entry into the Nepal Valley . The Kiratas and the Newars . First Settlement in the Valley . Why they were called Newars . The Newars and the Lichhavis . The Newars of Kathmandu . Origin . Religion . Newari Festivals . Customs and Manners . Caste System . Occupation. Language and Cultural Achievements Relation with India . Art and Architecture in Nepal . The Stupas . Swayambhunath and Bauddha . The Temples . The Nepal Style . Sculpture . Painting . Gift to Asia . Modern Art . ANCIENT NEPAL EARLY NEPAL Sources . The Dawn ... The Kirata Dynasty . The Pre-Kirata Period . The Kirata Rulers 4 ... The Lichhavi Dynasty . / . The So-called Lichhavi Character of Nepal Constitution Genealogy & Chronology . Inscriptions . The Date of Manadeva . The Era of the Earlier Inscriptions . The Epoch Year of the First Series of Inscriptions . Facts of History as Cited by Manadeva's Changu Inscription . Chronology Recitified . Manadeva's Successors . The Ahir Guptas . Religion in Early Nepal . CHAPTERIV : GUPTA SUCCESSORS The Tibetan Era of 595 A.D. TheEpochof the Era . The Epoch year of the Era . Amsuvarman's Documents . -

TITLE a Guide to Asian Collectionsin American Museums. INSTITUTION ASIA Society, New York, N.Y

DOCUMENT RESUME SO 000 409 ED 080 388 TITLE A Guide to Asian Collectionsin American Museums. INSTITUTION ASIA Society, New York, N.Y. PUB DATE Nov 64 NOTE 39p, EDRS PRICE mF -$0.65 HC-$3.29 *Asian History; DESCRIPTORS Art kwreciation; Arts Centers; *Asian Studies; Chinese Culture;Cross Cultural Studies; Cultural Education; *Museums;*Non Western Civilization; Painting; ResourceGuides; Sculpture; Visual Arts ABSTRACT Asian art collections held intwenty-one states and of in Canadian museums andgalleries, representing a cross-section study material available tothe public, are listed inthis guide. others are Some of the collectionslisted are broad in scope while confined to a special country..Asia asrepresented in the publication is defined as including allcountries from Afghanistan to Japan.. Information given includes name,address, hours, and directorof the descriptions, written by directors,contain information museum. Brief and concerning the history, scope,and size of collections..Museums brief galleries are listed alphabeticallyby state..In addition to a introduction, the publicationincludes; 1) an outline ofhistoric periods in China, India, and Japan(to serve as a studyaid); 2)indices of countries representedand museums and gallerieslisted; 3) a glossary of foreign orunfamiliar terms; and 4) a selected bibliography of significant booksfor additional information(SJM) U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION i WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEENREPRO OUCEO EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN STING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATEO DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EOUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Ii7 A GUIDE TO ASIAN COLLECTIONS IN AMERICAN MUSEUMS k .. THE ASIA SOCIETY NEW YORK PREFACE Throughout the country an unparalleled interest in art and Asian studies is taking place. -

The Dr Paul Sutherland Collection Auction Monday 29 May 2017 at 6Pm

Guy Earl-Smith Art &Antiquities The Private Collection of Huang Yu-Li and Other Vendors Auction Monday 29 May 2017 i Guy Earl-Smith Art &Antiquities East Australian Trading Consolidated The Private ABN 70 095 511 603 Enquiries Collection Guy Earl-Smith Email: [email protected] Tel: 0421 476 848 of Huang David Longfield Email: [email protected] Tel: 0410 519 685 Yu-Li Designed and produced by and Other Vendors, including The Dr Paul Sutherland Collection Auction Monday 29 May 2017 at 6pm ii Contents ImportantIm Information for Buyers Page ii TThe Hwang Yu-Li Story Page iv CChinese Painted Clay Sculptures Page vi PrivateP Collection of Huang Yu-Li Lots 1-156 OtherO Vendors Lots 157-169 DrD Paul Sutherland Collection Lots 170-213 TermsT and Conditions Page 150 Image Lot 55. A Painted Clay Ming Dynasty Sculpture of Guanyin, c. 1368-1644 i Important Information for Buyers This auction is sold in Australian Dollars and subject to Absentee Bidding Method of Payment Endangered Species and U.S Trade the information below and the Terms & Conditions of For prospective buyers unable to attend the auction, Payments for purchases can be made with bank cheque, Restrictions Business printed at rear of this catalogue. all bids should be lodged as Absentee Bids prior to cash, Paypal or Direct Banking Transfers (Wire Transfers). Prospective purchasers are advised that several the auction. Absentee Bids must be advised in writing. All international payments exceeding AUD500 must be countries prohibit the importation of property containing Buyer Registration Appropriate forms are available upon request. -

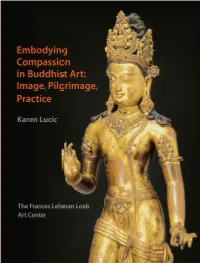

Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice

Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice THE FRANCES LEHMAN LOEB ART CENTER Embodying Compassion 1 Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice Karen Lucic The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center 2 Embodying Compassion Embodying Compassion 3 Lenders and Donors to the Exhibition Contents American Museum of Natural History, New York 6 Acknowledgments Asia Society, New York 7 Note to the Reader Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art 9 Many Faces, Many Names: Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva of Compassion The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 49 Embodying Compassion in Buddhist Art: The Newark Museum Catalogue Entries Princeton University Art Museum 49 Image The Rubin Museum of Art, New York 59 Pilgrimage Daniele Selby ’13 65 Practice 73 Glossary 76 Sources Cited 80 Photo Credits Front cover illustration: Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (detail), Nepal, The exhibition and publication ofEmbodying Compassion in Transitional period, late 10th–early 11th century; gilt copper alloy with Buddhist Art: Image, Pilgrimage, Practice are supported by inlays of semiprecious stones; 26 3/4 x 11 1/2 x 5 1/4 in.; Asia Society, E. Rhodes & Leona B. Carpenter Foundation; The Henry Luce New York, Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, 1979.47. Foundation; ASIANetwork Luce Asian Arts Program; John Stuart Gordon ’00; Elizabeth Kay and Raymond Bal; Ann Kinney Back cover illustration: Kannon (Avalokiteshvara), (detail), Japanese, ’53 and Gilbert Kinney. It is organized by The Frances Lehman Edo period (1615–1868); hanging scroll, ink and color on silk; image: Loeb Art Center and on view from April 23 to June 28, 2015. 61 7/8 x 33 in., mount: 87 7/8 x 39 1/2 in.; Gift of Daniele Selby ’13, The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, 2014.20.1. -

A Tribute to Hinduism

Quotes Basics Science History Social Other Search h o m e s u v a r n a b h u m i : g r e a t e r i n d i a c o n t e n t s Only Since World War II has the term Southeast Asia been used to describe the area to the east of India and to the south of China, which includes the Indo-Chinese Peninsula, the Malay Archipelago and the Philippines, roughly forming a circle from Burma through Indonesia to Vietnam. Before the term Southeast Asia became common usage, the region was often described as Further or Greater India, and it was common to describe the Indonesian region or Malay Archipelago as the East Indies. The reason may be found in the fact that, prior to Western dominance, Southeast Asia was closely allied to India culturally and commercially. The history of Indian expansion covers a period of more than fifteen hundred years. This region was broadly referred to by ancient Indians as Suvarnabhumi (the Land of Gold) or Suvarnadvipa (the Island of Gold), although scholars dispute its exact definition. Sometimes the term is interpreted to mean only Indonesia or Sumatra. Arab writers such as Al Biruni testify that Indians called the whole Southeast region Suwarndib (Suvarnadvipa). Hellenistic geographers knew the area as the Golden Ghersonese. The Chinese called it Kin-Lin; Kin means gold. During the last two thousand years, this region has come under the influence of practically all the major civilizations of the world: Indian, Chinese, Islamic, and Western. -

She Who Slays the Buffalo-Demon Divinity, Identity, and Authority in Iconography of Mahiasuramardini Caleb Simmons

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 She Who Slays the Buffalo-Demon Divinity, Identity, and Authority in Iconography of Mahiasuramardini Caleb Simmons Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES SHE WHO SLAYS THE BUFFALO-DEMON DIVINITY, IDENTITY, AND AUTHORITY IN ICONOGRAPHY OF MAHI!!SURAMARDIN" By CALEB SIMMONS A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Caleb Simmons defended on 8 April 2008. ____________________________________ Kathleen M. Erndl Professor Directing Thesis ____________________________________ Bryan J. Cuevas Committee Member ____________________________________ Adam Gaiser Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________________ John Corrigan, Chair, Religion Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii Dedicated to ~Mama and Daddy~ for all of the sacrifices that you have made for me throughout the years. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my most sincere thanks to the many people that have aided and inspired me throughout the course of my MA work. I must start by thanking the faculty and staff of the Department of Religion at Florida State University. I will forever be indebted to them for the opportunity to study with such gifted mentors. I especially owe the utmost gratitude to Professor Kathleen Erndl for all of her thoughtful guidance and insight that helped develop education and my research.