Ref Or I Resumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antonio G. Lauer, Aka Tomislav Gotovac, and the Man

Share Ana Ofak Gentleman Next Door: Antonio G. Lauer, a.k.a. Tomislav Gotovac, and the Man Undressed in Times of Socialism Tenderness, unburdened sentiments, and freedom are rarely found in the cinematographic spectrum of the 1950s. Arne Mattsson’s 1951 film One Summer of Happiness already assures us with its title that we are going to see something perishable. Just as the water of the lake where the two protagonists swim glitters only on the surface, and only when the sun is going down, the moments they share in this fluid and forgiving medium are already doomed. The film’s rather predictable boy-meets-girl story nevertheless presents one trope that was scandalous for the time: nudity. And we are not just talking about contours of naked female and male bodies at play, but a clear view of erect nipples. This came as close to sex on screen as 1950s audiences were likely to see. After receiving a Golden Bear at the second Berlin International Film Festival in 1952, the movie only made it to New York City in 1957. However, it was shown in Zagreb in 1952 at Kino Prosvjeta (Cinema Education), a movie theater on the ground floor of a former military hospital on Krajiška Street. Every fifteen-year-old seeing it must have gleaned enough material for an outburst of romantic or raunchy fantasies—except for one. Antonio G. Lauer, a.k.a. Tomislav Gotovac, decided many years after One Summer of Happiness that “what was implanted in [his] artistic brain [back then] was that nudity was one of the most important things through which you can tell the world your attitude toward it.”1 Tomislav Gotovac, Lying Naked on the Asphalt, Kissing the Asphalt (Zagreb, I love you), 1980. -

A Collection of Practical Suggestions Reprinted from Issues of Australian

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 101 302 CS 201 048 TITLE Resources I--Ideas for English Lessons; A Collection of Practical Suggestions Reprinted from issues of "English in Australia." INSTITUTION Australian Association for the Teaching of English. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 66p. AVAILABLE PROMThe Publications Secretary, AATE, 163A Greenhill Road, Parkside, South Australia 5063 ($1.20 including postage; Australian money) EDRS PRICE MP-S0 .76 HC$3.32 PLUS ppSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; *Class Activities; Classroom Materials; *Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *English instruction; *instructional Materials; Language Arts; *Lesson Plans; Resource Materials ABSTRACT This monograph contains 47 lesson ideas that elementary and secondary English tectovhers mayfind'useful for classroom activities. Each item dem:L.135es the aim of the lesson and the grade level and provides Suggestions on how to carry out the lesson. Some of the activities suggested include "Advertising a Play'', "Write Your Own Obituary," "Studying the Novel through Poetry," "Recognizing a Speaker's Tone," "Book Display for Reluctant Readers," "Public Speaking," "Creative Writing," and "Man and His Earth." Depending on the aims of the lessons, additional instructional materials and reading materials are recommended. This collection of practical suggestions for class activities is reprinted from past issues of "Resources," which appears regularly inunglish in Australia.m (RB) RESOURCES IDEAS FOR ENGLISH LESSONS A collection of practical suggestions reprinted from issues of "English In Australia". I 0 U.S. DEPARTMENT .., HEALTH, EDUCATION A VULPATIE NATIONAL iNSTITUtelle EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS SEEN REPRO OuCEb EXACTLY AS ROC, web FROM THE PERSON OR OISCIANIZATIDY ORIGIN MIND It POINTS OF VIEW OR I1INIONS STATED 00 NOT NECESSARIL I REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITutE or EDUCATION POSITION OR POLu AUSTRALIAN ASSOCIATION POP THE TEACHING OP ENGLISH, INC, 1974 RESOURCES I IDEAS FOR ENGLISH LESSONS Copyright © 1974 by The Australian Association for the Teaching of English, Inc. -

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

1. Eva Dahlbeck - “Pansarskeppet Kvinnligheten”

“Pansarskeppet kvinnligheten” deconstructed A study of Eva Dahlbeck’s stardom in the intersection between Swedish post-war popular film culture and the auteur Ingmar Bergman Saki Kobayashi Department of Media Studies Master’s Thesis 30 ECTS credits Cinema Studies Master’s Programme in Cinema Studies 120 ECTS credits Spring 2018 Supervisor: Maaret Koskinen “Pansarskeppet kvinnligheten” deconstructed A study of Eva Dahlbeck’s stardom in the intersection between Swedish post-war popular film culture and the auteur Ingmar Bergman Saki Kobayashi Abstract Eva Dahlbeck was one of Sweden’s most respected and popular actresses from the 1940s to the 1960s and is now remembered for her work with Ingmar Bergman, who allegedly nicknamed her “Pansarskeppet kvinnligheten” (“H.M.S. Femininity”). However, Dahlbeck had already established herself as a star long before her collaborations with Bergman. The popularity of Bergman’s three comedies (Waiting Women (Kvinnors väntan, 1952), A Lesson in Love (En lektion i kärlek, 1954), and Smiles of a Summer Night (Sommarnattens leende, 1955)) suggests that they catered to the Swedish audience’s desire to see the star Dahlbeck. To explore the interrelation between Swedish post-war popular film culture and the auteur Bergman, this thesis examines the stardom of Dahlbeck, who can, as inter-texts between various films, bridge the gap between popular film and auteur film. Focusing on the decade from 1946 to 1956, the process whereby her star image was created, the aspects that constructed it, and its relation to her characters in three Bergman titles will be analysed. In doing so, this thesis will illustrate how the concept “Pansarskeppet kvinnligheten” was interactively constructed by Bergman’s films, the post-war Swedish film industry, and the media discourses which cultivated the star cult as a part of popular culture. -

Book Reviews

10.1515/nor-2017-0406 Nordicom Review 38 (2017) 1, pp. 127-135 Book Reviews Editors: Ragnhild Mølster & Maarit Jaakkola Martin Eide, Helle Sjøvaag & Leif Ove Larsen (eds.) Journalism Re-Examined: Digital Challenges and Professional Orientation (Lessons from Northern Europe) Intellect Ltd., 2016, 215 p. The question of a sustainable path for journal- because of its institutional nature. Chapter ism has been the subject of interest for many 5 by Jan Fredrik Hovden is a good example observers, both in the Nordic countries and of this. Despite many changes in the market beyond. The book Journalism Re-Examined and working conditions, the values of inves- presents a number of well-researched and em- tigative journalism persist and they are even pirically enlightening case studies that show becoming more influential. Hovden’s impres- the depth and variety of the journalistic pro- sive systematic approach and large amount of fession, which is a helpful invitation to think quantitative data from surveys with Nordic about the topic in terms of institutional theory journalism students from 2005-2012 enable and to see journalism as an institution or field, him to conclude that ‘the slimming down of and thus more than a mere profession. the multifaceted task for journalist in modern Two of the editors, Martin Eide and Helle society is ambiguous not only in its causes Sjøvaag, set out the new institutionalist theo- but also in its consequences’. This he sees in retical framework, which they propose as a terms of increased specialisation and as an helpful tool to analyse the challenges facing example of the re-orientations of journalism journalism in a digital age. -

Itatfe's Budget Totals $1.78 Billion by DAVID M

CgUfge Stpientf to Get State Lottery Windfall SEE STORY BELOW y and Cold and cold today. Clear cold tonight. Fair, milder ttW and Thursday. (See Details, Page 2) EDITION Monmouth County9? Home Newspaper for 92, Years 9$ IM). 160 RED BANK, N. j, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 16,1971 18 PAGES TEN CENTS itatfe's Budget Totals $1.78 Billion By DAVID M. GOLDBERG admission of 17,000 more stu- lion in supplemental appropri- vetoes are rare. was sufficient because only $6 TRENTON (AP) - Gov. dents to the state college and ations has already been made. The main method of balanc- million a year of that money William T. CahDl presented university system to be fi- If that figure were repeated ing the budget was through was spent and the $23 million the legislature today with a nanced with the heavier than this year, the state would go the use of what was called jjeed only last for two years $1.78 billion budget that uses a anticipated lottery receipts. over the limit, but' Cahill said "lapses," which added an ad- more. series of bookkeeping trans- But Cahill conceded the he expects to hold the figure ditional $65 million in revenue, "No municipality could pos- fers to avoid new taxes. But budget is largely an austerity down. •compared to $21 million added sibly be hurt by this," he said Cahill warned that the finan- budget which holds the line in The governor's recommen- for this year through the same at the news conference at cial maneuverings can last the face of numerous depart- dations.now go to the legisla- methods. -

Table of Contents

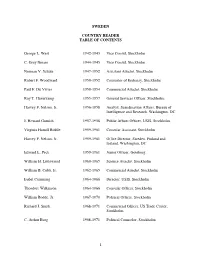

SWEDEN COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS George L. West 1942-1943 Vice Consul, Stockholm C. Gray Bream 1944-1945 Vice Consul, Stockholm Norman V. Schute 1947-1952 Assistant Attaché, Stockholm Robert F. Woodward 1950-1952 Counselor of Embassy, Stockholm Paul F. Du Vivier 1950-1954 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Roy T. Haverkamp 1955-1957 General Services Officer, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1956-1958 Analyst, Scandinavian Affairs, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC J. Howard Garnish 1957-1958 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Virginia Hamill Biddle 1959-1961 Consular Assistant, Stockholm Harvey F. Nelson, Jr. 1959-1961 Office Director, Sweden, Finland and Iceland, Washington, DC Edward L. Peck 1959-1961 Junior Officer, Goteborg William H. Littlewood 1960-1965 Science Attaché, Stockholm William B. Cobb, Jr. 1962-1965 Commercial Attaché, Stockholm Isabel Cumming 1964-1966 Director, USIS, Stockholm Theodore Wilkinson 1964-1966 Consular Officer, Stockholm William Bodde, Jr. 1967-1970 Political Officer, Stockholm Richard J. Smith 1968-1971 Commercial Officer, US Trade Center, Stockholm C. Arthur Borg 1968-1971 Political Counselor, Stockholm 1 Haven N. Webb 1969-1971 Analyst, Western Europe, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington, DC Patrick E. Nieburg 1969-1972 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Stockholm Gerald Michael Bache 1969-1973 Economic Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1969-1974 Desk Officer, Scandinavian Countries, USIA, Washington, DC William Bodde, Jr. 1970-1972 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC Arthur Joseph Olsen 1971-1974 Political Counselor, Stockholm John P. Owens 1972-1974 Desk Officer, Sweden, Washington, DC James O’Brien Howard 1972-1977 Agricultural Officer, US Department of Agriculture, Stockholm John P. Owens 1974-1976 Political Officer, Stockholm Eric Fleisher 1974-1977 Press Attaché, USIS, Stockholm David S. -

Swedish Film and Television Culture, 15 Hp, FV1027

Swedish Film and Television Culture, 15 hp, FV1027 Kursansvarig: Mariah Larsson [email protected] HT2014 Films: They Call us Misfits (Dom Kallar oss Mods, Stefan Jarl and Jan Lindquist, 1968, 101 min) The Girls (Flickorna, Mai Zetterling, 1968, 100 min) I livets vår (Paul Garbagni, 1912, 60 min) Ingeborg Holm (Victor Sjöström, 1913, 72 min) Charlotte Löwensköld (Gustaf Molander, 1930, 94 min) Erotikon (Mauritz Stiller, 1920, 106 min) One Summer of Happiness (Hon dansade en sommar, Arne Mattsson, 1951, 103 min) Wild Strawberries (Smultronstället, Ingmar Bergman, 1957, 91 min) Show Me Love (Fucking Åmål, Lukas Moodysson, 1998, 89 min) Let the Right One In (Låt den rätte komma in, Tomas Alfredson, 2008, 114 min) Call Girl (Mikael Marcimain, 2012, 140 min) Books: Corrigan, Timothy: A Short Guide to Writing About Film. 7th ed. 2010 (Note: For students who have extensive prior experience of studying film this book may be considered as ”additional reading”. It is compulsory reading for those new to Cinema Studies) Larsson, Mariah and Anders Marklund, (eds), Swedish Film: An Introduction and Reader. 2010. Soila, Tytti, Astrid Söderbergh Widding, and Gunnar Iversen. Nordic National Cinemas. London and New York: Routledge, 1998 Westerståhl Stenport, Anna. Lukas Moodysson's Show me Love. Seattle, Wn.: University of Washington Press, 2012 Articles and book chapters. Will be available in a reader or on Mondo: Bazalgette, Cary and Staples, Terry, “Unshrinking the Kids. Children’s Cinema and the Family Film” in In Front of the Children. Screen Entertainment and Young Audiences, ed. by Cary Bazalgette and David Buckingham (London: BFI, 1995), pp. -

TIONAL *Rem Rm

46' - INZ "731¡':4 .....emeem_e_j___ ..10010 ewer !!! -WM TIONAL *rem rm. ilKlminjwje .... ..... Who What re5e VV ere Li'Zr2 rt eLevlb,e www.americanradiohistory.com ...For America's Leaders of Business and Industry... Tit C Ivz ERCZiL >Z0 GEOERRL National Screen Service brings ELELTRIL ek to the Television advertiser 35 1K, years of recognized experience AMERICAN MOTORS in the production of advertising NASH film' designed to convey your 11111. KELVINATOR ¡REFRIGERATORS Air message vividly, succinctly, WASHERS 4 successfully. Z7 ELGIN Cf WATCHES Some of the distinguished leaders Y NATIONAL M of American business who have IA BROAD- e\ MS CASTING availed themselves of this exper- CO. - ience are listed. Scores of others \ HAMILTON e - large and small - have found, \ WATCHES \ , 1aß through their advertising ir agen- ft NATIONAL cies, that National Screen Service GYPSUM .11 is synonymous with quality! `I. II Du PONT- RAiIoRAISeteed SERVICE NEW YORK 1600 BROADWAY CIRCLE 6-5100 HOLLYWOOD 1026 SANTA MONICA BLVD., GLADSTONE 3136 www.americanradiohistory.com "GENERAL SPORTS TIME" sponsored by General Tire & Rubber Co. "BETHLEHEM SPORTS TIME" . sponsored by Betlfdehem Steel Co. "THIS WEEK IIN SPORTS" . sponsored by International News Service HARRY WISMER General Teleradio, Inc. www.americanradiohistory.com 5 NEW GUILD WINNERS to build station ratings and sponsor sales PAUL COATES' CONFIDENTIAL FILE Exposes rackets, unmasks social problems, reports on unusual personalities that make up America. Tremendous sales impact ... Los Angeles' highest rated local show. Dynamic, exciting, unique! THE GOLDBERGS starring GERTRUDE BERG They've moved to Haverville, U.S.A. and there's a fresh new flavor to America's most beloved family show as it embarks on a heart-warming new series of adventures. -

Brazilian Cinema at the Berlin International Film Festival

1 Brazilian Cinema at the Berlin International Film Festival Carolina Rocha Published: March 06, 2019 Figure 1. OS CAFAJESTES, Films sans Frontières © original copyright holders Film scholar Marijcke de Valck argues that film festivals “are sites of passage that function as the gateways to cultural legitimation” (De Valck 2007: 38). More recently, Andreas Kötzing and Caroline Moine have pointed out the political dimensions of these cultural events, particularly during the second half of the twentieth century: Film festivals, whether they called themselves international or not, were at the epicenter of the various circulations, exchanges, and tensions that fueled the economic and cultural development of the Cold War. (Kötzing/Moine 2017: 10) Building on these insights and utilizing multiple film reviews, this article analyzes the performance of two Brazilian films—OS CAFAJESTES (BRAZIL 1962) and OS FUZIS (BRAZIL/ARGENTINA 1964)—that were invited to be screened at the Berlin International Film Festival in the early 1960s and were Research in Film and History ‣ New Approaches 2019 ©The Author(s) 2019. Published by Research in Film and History. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons BY–NC–ND 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). 2 both nominated for the Golden Bear. I argue that the Berlin International Film Festival benefited from an interest in Brazilian cinema at a time when the politics of the Cold War challenged cinema’s role as a bridge between East and West. As I will show below, during the Berlin International Film Festival’s first decade, only films from Western Europe and the United States received Golden Bears. -

Teegarden/Nasht Digital Stock Images of Movie Memorabilia COL LE CTION Film Poster List

HE Teegarden/NashT Digital Stock Images of Movie Memorabilia COL LE CTION Film Poster List Title Year Genre Director Actor Style A.I. - Artificial Intelligence 2001 Sci-Fi Spielberg Osment, Law 1 Sheet Rolled A.I. - Artificial Intelligence 2001 Sci-Fi Spielberg Osment, Law 1 Sheet Rolled Advance Abandon 2002 Drama Gaghan Holmes, Bratt, Hunnam 1 Sheet Rolled Abduction 2011 Action Singleton Lautner, Molina, Weaver 1 Sheet Rolled About a Boy 2002 Drama Weitz Grant, Hoult, Collette 1 Sheet Rolled About Last Night 1986 Drama Zwick Lowe, Moore, Belushi 1 Sheet Folded About Schmidt 2002 Comedy Payne Nicholson, Bates 1 Sheet Rolled Above All Law 1920’s Drama May Fonss, May Insert Absence of Malice 1981 Drama Pollack Newman, Field 1 Sheet Folded Absolute Beginners 1986 Musical Temple Bowie 1 Sheet British Absolute Beginners 1986 Musical Temple Bowie 1 Sheet Rolled Academy Awards 51st 1978 Oscar 1 Sheet Folded Academy Awards 53rd 1980 Oscar 1 Sheet Folded Academy Awards 64th 1992 Oscar 1 Sheet Folded Video Accident 1967 Drama Losey Bogarde, Baker, Seyrig, York 1 Sheet Folded Accidental Tourist 1989 Drama Kasdan Hurt, Turner, Davis 1 Sheet Rolled Accompanist, The 1993 Foreign Miller Bohringer 1 Sheet Rolled Accused 1988 Drama Kaplan Foster 1 Sheet Folded Ace Ventura When Nature Calls 1995 Comedy Oedekerk Carrey 1 Sheet Rolled Across the Universe 2007 Musical Taymor Wood, Sturgess 1 Sheet Rolled Act of the Heart 1971 Drama Almond Bujold, Sutherland 1 Sheet Folded Acting It Out 1992 Foreign Wortman Vogel 1 Sheet Folded German Adam 2009 Drama Mayer -

Two Nordic Existential Comedies: Smiles of a Summer Night and the Kingdom

Two Nordic existential comedies: Smiles of a Summer Night and The Kingdom Grodal, Torben Kragh Published in: Journal of Scandinavian Cinema DOI: 10.1386/jsca.4.3.231_1 Publication date: 2014 Citation for published version (APA): Grodal, T. K. (2014). Two Nordic existential comedies: Smiles of a Summer Night and The Kingdom. Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, 4(3), 231-238. https://doi.org/10.1386/jsca.4.3.231_1 Download date: 29. sep.. 2021 BK;9, +!hh&*+)Ç*+0Afl]dd][lDaeal]\*(), BgmjfYdg^K[Yf\afYnaYf;af]eY Ngdme],FmeZ]j+ *(),Afl]dd][lDl\9jla[d]&=f_dak`dYf_mY_]&\ga2)(&)+0.'bk[Y&,&+&*+)W) Copyright intellect 2015 do not k`gjlkmZb][l LGJ:=F?JG<9D Mfan]jkalqg^;gh]f`Y_]f LogFgj\a[]pakl]flaYd distribute [ge]\a]k2Kead]kg^Y Kmee]jFa_`lYf\ L`]Caf_\ge 9:KLJ9;L tors best known for tragic films that C=QOGJ<K evoke existential angst and melan- 1. The article analyses Ingmar Bergman’s Lars von Trier choly. The driving force of the deep 2. Smiles of a Summer Night and Lars Ingmar Bergman pain in their tragic films is linked 3. von Trier’s The Kingdom. By means of comedy theory to concerns about human nature, 4. evolution and-neurology-based humour social ritual especially the inability to establish 5. theory it shows how the two directors – film aesthetics bonds to other people and the prev- 6. who ordinarily make dark and tragic Smiles of a Summer alence of selfish desires (see Grodal 7. films – use humour mechanisms from Night 2009, 2012 on von Trier).