Ecology and Evolution of Cuckoo Bumble Bees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bumble Bees of the Western United States” by Jonathan Koch, James Strange, and Paul Williams (2012)

Adapted from the “Bumble Bees of the Western United States” by Jonathan Koch, James Strange, and Paul Williams (2012). Bumble bees are one of Wyoming’s most important and mild-mannered pollinators. There are more than 20 species in Wyoming, which you can often tell apart by the color patterns on their bodies. This guide shows color patterns for queen bees only, and some species can have multiple queen Bumble patterns! of Bees Areas in yellow indicate where each species Wyoming is found in Wyoming wyomingbiodiversity.org Black Tail Bumble Bee How can you tell Bombus melanopygus it's a bumble bee? Common Bumble bees are the largest bodied bees in Wyoming. Queens can be up to two inches long, but most queens and workers are somewhat smaller than that. They're very hairy all over their bodies, and carry pollen in “baskets” on their hind legs. Did you find a bumble bee? Submit your observation to the Xerces Society of Invertebrate Conservation's website: BumbleBeeWatch.org You can be a member of the citizen science community! Brown-Belted Bumble Bee California Bumble Bee Bombus griseocollis Bombus californicus Common Uncommon Central Bumble Bee Cuckoo Bumble Bee Bombus centralis Bombus insularis Common Common Fernald Cuckoo Bumble Bee Forest Bumble Bee Bombus fernaldae Bombus sylvicola Uncommon Uncommon Frigid Bumble Bee Fuzzy-Horned Bumble Bee Bombus frigidus Bombus mixtus Rare Common Half-Black Bumble Bee High Country Bumble Bee Bombus vagans Bombus balteatus Common Common Hunt’s Bumble Bee Morrison Bumble Bee Bombus huntii Bombus morrisoni Common Common Nevada Bumble Bee Red-Belted Bumble Bee Bombus nevadensis Bombus rufocinctus Common Common Suckley Cuckoo Bumble Bee Bombus suckleyi Red-Belted Bumble Bee, continued Uncommon Two-Form Bumble Bee Western Bumble Bee Bombus bifarius Bombus occidentalis Common Rare throughout much of its range, but common in Wyoming. -

Pollination of Cultivated Plants in the Tropics 111 Rrun.-Co Lcfcnow!Cdgmencle

ISSN 1010-1365 0 AGRICULTURAL Pollination of SERVICES cultivated plants BUL IN in the tropics 118 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO 6-lina AGRICULTUTZ4U. ionof SERNES cultivated plans in tetropics Edited by David W. Roubik Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Balboa, Panama Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations F'Ø Rome, 1995 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-11 ISBN 92-5-103659-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. FAO 1995 PlELi. uion are ted PlauAr David W. Roubilli (edita Footli-anal ISgt-iieulture Organization of the Untled Nations Contributors Marco Accorti Makhdzir Mardan Istituto Sperimentale per la Zoologia Agraria Universiti Pertanian Malaysia Cascine del Ricci° Malaysian Bee Research Development Team 50125 Firenze, Italy 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Stephen L. Buchmann John K. S. Mbaya United States Department of Agriculture National Beekeeping Station Carl Hayden Bee Research Center P. -

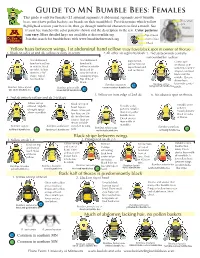

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females

Guide to MN Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble Three small bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns ® can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Bee Front of face Squad Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee C patch. two-spotted bumble bee C brown-belted bumble bee C 5. Yellow on front edge of 2nd ab 6. No obvious spot on thorax. 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

CUTOVERS AS POTENTIAL SUITABLE BEE HABITATS By

CUTOVERS AS POTENTIAL SUITABLE BEE HABITATS by Jasmine R. Pinksen A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science, Honours Environmental Science, Grenfell Campus Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2017 Corner Brook Newfoundland 2 Grenfell Campus Environmental Science Unit The undersigned certify that they have read, and recommend to the Environmental Science Unit (School of Science and the Environment) for acceptance, a thesis entitled “Cutovers as Potential Suitable Bee Habitats” submitted by Jasmine R. Pinksen in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science, Honours. _____________________________ Dr. Julie Sircom (thesis supervisor) _____________________________ Dr. Erin Fraser _____________________________ Dr. Joe Bowden April ____, 2017 3 Acknowledgements Thank you to the valuable research team members who helped with data collection for this project, Geena Arul Jothi, Megan Trotman, Tiffany Fillier, Erika Young, Nicole Walsh, and Abira Mumtaz. Thank you to Barry Elkins with Corner Brook Pulp and Paper Ltd. for financial support in 2015, maps of the logging areas around Corner Brook, NL, and his recommendations on site selection. Special thank you to my supervisor Dr. Julie Sircom, Dr. Erin Fraser and Dr. Joe Bowden for their feedback and support. 4 Abstract Bees are of great importance for pollinating agricultural crops and wild plant communities. Direct human activities such as urbanization, pesticide use, pollution, and introduction of species and pathogens as well as climate change are resulting in habitat loss and fragmentation for bees, causing declines in bee populations worldwide. Lack of suitable habitat is considered to be one of the main factors contributing to these declines. -

Bumble Bees of CT-Females

Guide to CT Bumble Bees: Females This guide is only for females (12 antennal segments, 6 abdominal segments, most bumble bees, most have pollen baskets, no beards on their mandibles). First determine which yellow Three small eyes highlighted section your bee is in, then go through numbered characters to find a match. See if your bee matches the color patterns shown and the description in the text. Color patterns can vary. More detailed keys are available at discoverlife.org. Top of head Join the search for bumble bees with www.bumbleebeewatch.org Front of face Cheek Yellow hairs between wings, 1st abdominal band yellow (may have black spot in center of thorax) 1. Black on sides of 2nd ab, yellow or rusty in center 2.All other ab segments black 3. 2nd ab brownish centrally surrounded by yellow 2nd abdominal 2nd abdominal Light lemon Center spot band with yellow band with yellow hairs on on thorax with in middle, black yellow in middle top of head and sometimes faint V on sides. Yellow bordered by and on thorax. shaped extension often in a “W” rusty brown in a back from the shape. Top of swooping shape. middle. Queens head yellow. Top of head do not have black. Bombus impatiens Bombus affinis brownish central rusty patched bumble bee Bombus bimaculatus Bombus griseocollis common eastern bumble bee patch. two-spotted bumble bee brown-belted bumble bee 4. 2nd ab entirely yellow and ab 3-6 black 5. No obvious spot on thorax. Yellow on top Black on top of Variable color of head. -

Scottish Bees

Scottish Bees Introduction to bees Bees are fascinating insects that can be found in a broad range of habitats from urban gardens to grasslands and wetlands. There are over 270 species of bee in the UK in 6 families - 115 of these have been recorded in Scotland, with 4 species now thought to be extinct and insufficient data available for another 2 species. Bees are very diverse, varying in size, tongue-length and flower preference. In the UK we have 1 species of honey bee, 24 species of bumblebee and the rest are solitary bees. They fulfil an essential ecological and environmental role as one of the most significant groups of pollinating insects, all of which we depend upon for the pollination of 80% of our wild and cultivated plants. Some flowers are in fact designed specifically for bee pollination, to the exclusion of generalist pollinators. Bees and their relatives Bees are classified in the complex insect order Hymenoptera (meaning membrane-winged), which also includes many kinds of parasitic wasps, gall wasps, hunting wasps, ants and sawflies. There are about 150,000 species of Hymenoptera known worldwide separated into two sub-orders. The first is the most primitive sub-order Symphyta which includes the sawflies and their relatives, lacking a wasp-waist and generally with free-living caterpillar-like larvae. The second is the sub-order Apocrita, which includes the ants, bees and wasps which are ’wasp-waisted’ and have grub-like larvae that develop within hosts, galls or nests. The sub-order Apocrita is in turn divided into two sections, the Parasitica and Aculeata. -

Competition Between Honeybees and Wild Danish Bees in an Urban Area

Competition between honeybees and wild Danish bees in an urban area Thomas Blindbæk 20072975 Master thesis MSc Aarhus University Department of bioscience Supervised by Yoko Luise Dupont 60 ECTS Master thesis English title: Competition between honeybees and wild Danish bees in an urban area Danish title: Konkurrence mellem honningbier og vilde danske bier i et bymiljø Author: Thomas Blindbæk Project supervisor: Yoko Luise Dupont, institute for bioscience, Silkeborg department Date: 16/06/17 Front page: Andrena fulva, photo by Thomas Blindbæk 2 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................ 5 Resumé ........................................................................................................ 6 Introduction .................................................................................................. 7 Honeybees .............................................................................................. 7 Pollen specialization and nesting preferences of wild bees .............................. 7 Competition ............................................................................................. 8 The urban environment ........................................................................... 10 Study aims ............................................................................................ 11 Methods ...................................................................................................... 12 Pan traps .............................................................................................. -

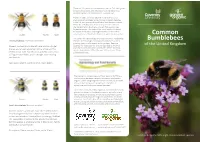

Bumblebee in the UK

There are 24 species of bumblebee in the UK. This field guide contains illustrations and descriptions of the eight most common species. All illustrations 1.5x actual size. There has been a marked decline in the diversity and abundance of wild bees across Europe in recent decades. In the UK, two species of bumblebee have become extinct within the last 80 years, and seven species are listed in the Government’s Biodiversity Action Plan as priorities for conservation. This decline has been largely attributed to habitat destruction and fragmentation, as a result of Queen Worker Male urbanisation and the intensification of agricultural practices. Common The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security is conducting Tree bumblebee (Bombus hypnorum) research to encourage and support bumblebees in food Bumblebees growing areas on allotments and in gardens. Bees are of the United Kingdom Queens, workers and males all have a brown-ginger essential for food security, and are regarded as the most thorax, and a black abdomen with a white tail. This important insect pollinators worldwide. Of the 100 crop species that provide 90% of the world’s food, over 70 are recent arrival from France is now present across most pollinated by bees. of England and Wales, and is thought to be moving northwards. Size: queen 18mm, worker 14mm, male 16mm The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security (CAFS) is a joint initiative between Coventry University and Garden Organic, which brings together social and natural scientists whose collective research expertise in the fields of agriculture and food spans several decades. The Centre conducts critical, rigorous and relevant research which contributes to the development of agricultural and food production practices which are economically sound, socially just and promote long-term protection of natural Queen Worker Male resources. -

The Reliability of Morphological Traits in the Differentiation of Bombus

Apidologie 41 (2010) 45–53 Available online at: c INRA/DIB-AGIB/EDP Sciences, 2009 www.apidologie.org DOI: 10.1051/apido/2009048 Original article The reliability of morphological traits in the differentiation of Bombus terrestris and B. lucorum (Hymenoptera: Apidae)* Stephan Wolf, Mandy Rohde,RobinF.A.Moritz Institut für Biologie, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Hoher Weg 4, 06099 Halle/Saale, Germany Received 16 December 2008 – Revised 18 April 2009 – Accepted 30 April 2009 Abstract – The bumblebees of the subgenus Bombus sensu strictu are a notoriously difficult taxonomic group because identification keys are based on the morphology of the sexuals, yet the workers are easily confused based on morphological characters alone. Based on a large field sample of workers putatively belonging to either B. terrestris or B. lucorum, we here test the applicability and accuracy of a frequently used taxonomic identification key for continental European bumblebees and mtDNA restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) that are diagnostic for queens to distinguish between B. terrestris and B. lucorum, two highly abundant but easily confused species in Central Europe. Bumblebee workers were grouped into B. terrestris and B. lucorum either based on the taxonomic key or their mtDNA RFLP. We also genotyped all workers with six polymorphic microsatellite loci to show which grouping better matched a coherent Hardy-Weinberg population. Firstly we could show that the mtDNA RFLPs diagnostic in queens also allowed an unambiguous discrimination of the two species. Moreover, the population genetic data confirmed that the mtDNA RFLP method is superior to the taxonomic tools available. The morphological key provided 45% misclassifications for B. -

Revealing the Hidden Niches of Cryptic Bumblebees in Great Britain: Implications for Conservation

Revealing the hidden niches of cryptic bumblebees in Great Britain: implications for conservation Article (Draft Version) Scriven, Jessica J, Woodall, Lucy C, Tinsley, Matthew C, Knight, Mairi E, Williams, Paul H, Carolan, James C, Brown, Mark J F and Goulson, Dave (2015) Revealing the hidden niches of cryptic bumblebees in Great Britain: implications for conservation. Biological Conservation, 182. pp. 126-133. ISSN 0006-3207 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/53171/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. -

Bumble Bees of the Susa Valley (Hymenoptera Apidae)

Bulletin of Insectology 63 (1): 137-152, 2010 ISSN 1721-8861 Bumble bees of the Susa Valley (Hymenoptera Apidae) Aulo MANINO, Augusto PATETTA, Giulia BOGLIETTI, Marco PORPORATO Di.Va.P.R.A. - Entomologia e Zoologia applicate all’Ambiente “Carlo Vidano”, Università di Torino, Grugliasco, Italy Abstract A survey of bumble bees (Bombus Latreille) of the Susa Valley was conducted at 124 locations between 340 and 3,130 m a.s.l. representative of the whole territory, which lies within the Cottian Central Alps, the Northern Cottian Alps, and the South-eastern Graian Alps. Altogether 1,102 specimens were collected and determined (180 queens, 227 males, and 695 workers) belonging to 30 species - two of which are represented by two subspecies - which account for 70% of those known in Italy, demonstrating the particular value of the area examined with regard to environmental quality and biodiversity. Bombus soroeensis (F.), Bombus me- somelas Gerstaecker, Bombus ruderarius (Mueller), Bombus monticola Smith, Bombus pratorum (L.), Bombus lucorum (L.), Bombus terrestris (L.), and Bombus lapidarius (L.) can be considered predominant, each one representing more than 5% of the collected specimens, 12 species are rather common (1-5% of specimens) and the remaining nine rare (less than 1%). A list of col- lected specimens with collection localities and dates is provided. To illustrate more clearly the altitudinal distribution of the dif- ferent species, the capture locations were grouped by altitude. 83.5% of the samples is also provided with data on the plant on which they were collected, comprising a total of 52 plant genera within 20 plant families. -

Positive and Negative Impacts of Non-Native Bee Species Around the World

Supplementary Materials: Positive and Negative Impacts of Non-Native Bee Species around the World Laura Russo Table S1. Selected references of potential negative impacts of Apis or Bombus species. Bold, underlined, and shaded text refers to citations with an empirical component while unbolded text refers to papers that refer to impacts only from a hypothetical standpoint. Light grey shading indicates species for which neither positive nor negative impacts have been recorded. “But see” refers to manuscripts that show evidence or describe the opposite of the effect and is capitalized when only contradictory studies could be found. Note that Apis mellifera scutellata (the “Africanized” honeybee), is treated separately given the abundance of research specifically studying that subspecies. Altering Non-native Nesting Floral Pathoens/ Invasive Introgres Decrease Pollination Species Sites Resources Parasites Weeds sion Plant Fitness Webs Apis cerana [1] [2] [1–3] [4] Apis dorsata Apis florea [5] [5] [37,45] But see [8–19] but [27–35] but [36–38] [39–43] [38,46,47] Apis mellifera [9,23–26] [4] [6,7] see [6,20–22] see [6] but see [44] [48,49] but see [50] Apis mellifera [51] but see [55–57] scutellata [52–54] Bombus [58,59] hortorum Bombus But see But see [60] [61] hypnorum [60] Bombus [62] [62,63] [26,64–66] [62] impatiens Bombus lucorum Bombus [28,58,59,6 [39] but see [67,68] [69,70] [36,39] ruderatus 9,71,72] [73] Bombus [59] subterraneous [67,70,74,75, [29,58,72,9 Bombus [25,26,70,7 [38,39,68,81,97,98 [4,76,88, [47,76,49,86,97 [74–76] 77–84] but 1–95] but terrestris 6,87–90] ] 99,100] ,101–103] see [85,86] see [96] Insects 2016, 7, 69; doi:10.3390/insects7040069 www.mdpi.com/journal/insects Insects 2016, 7, 69 S2 of S8 Table S2.